Switzerland is a country of 8.2 million

inhabitants, who mostly live outside one of

the six major cities: Zurich (384,786 inhabitants),

Geneva (191,557), Basel (174,491),

Lausanne (132,626), Berne (128,848) and

Winterthur (105,676) (Bundesamt für Statistik

2015). Switzerland is composed of 26 cantons

that enjoy a great deal of independence from the

federation. The jurisdiction of the emergency

service and hospital structure mainly lies with

these cantons (Wyss and Lorenz 2000), although

smaller cantons collaborate on many aspects.

For example, Basel University Hospital (its official

name translates as “University Hospital of

both Basels”) is a joint undertaking of the two

cantons Basel City and Basel Country.

Healthcare System

Every Swiss inhabitant, regardless of nationality,

is obliged to obtain healthcare insurance that in

its base tariff covers the costs of healthcare and

medication listed in a legal document. Insurance

for accidents, both during work or leisure,

is further provided through employers, who

insure their employees, usually with one of the

few major companies that provide this type of

coverage. The government subsidises insurance

fees for the needy.

The Swiss healthcare system is among the most

expensive in the world. In a 2006 comparison

of the costs of healthcare in OECD member

countries, Switzerland came second after the

United States, with average expenditure of 11.1%

of GDP on healthcare (OECD 2010). However,

in the most recent comparison of the quality

and performance of healthcare systems among

the 197 member states of WHO, Switzerland

was rated second in the overall quality of its

system (“attainment of WHO-goals”) and 20th

in performance (where quality is compared to

costs) (WHO 2000).

Emergency Medicine

As in most western countries, major emergency

rooms are usually part of a university hospital,

of which there are five in Switzerland: Basel,

Berne, Geneva, Lausanne and Zurich. In 2006

there were 138 hospital-based emergency rooms

in Switzerland, of which 21 (including the

five affiliated to a university) provide care to

more than 20,000 patients per year (Sanchez

et al. 2006).

As pre-hospital emergency services are largely

regulated (and often provided or commissioned)

by cantons, there is a great diversity of modes

of service. This article therefore focuses on the

situation and numbers from Berne.

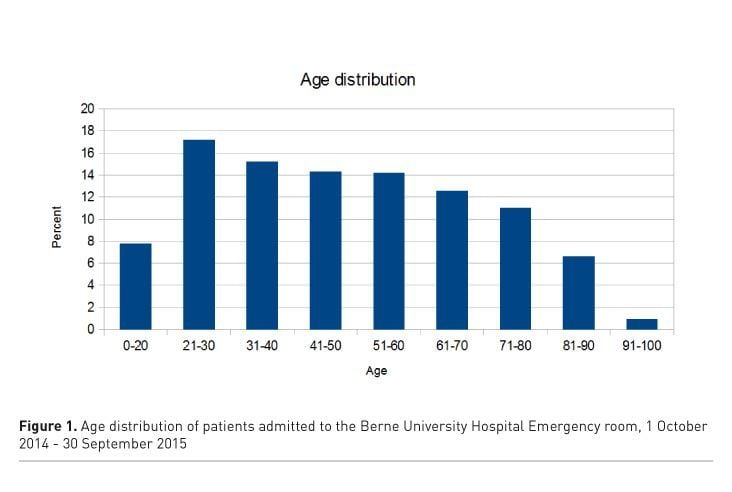

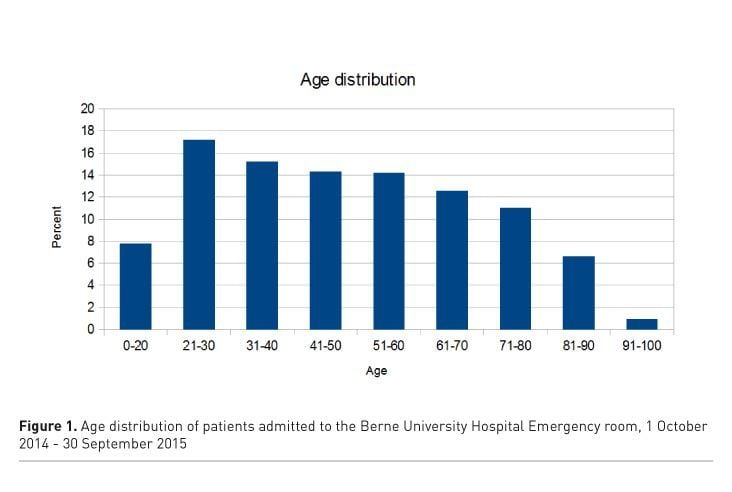

As the canton of Berne covers a large alpine

area and its

university hospital is the closest by

air to most of the Swiss Alps, patients injured

when farming the steep slopes or during sport

make up a comparatively large portion of emergency

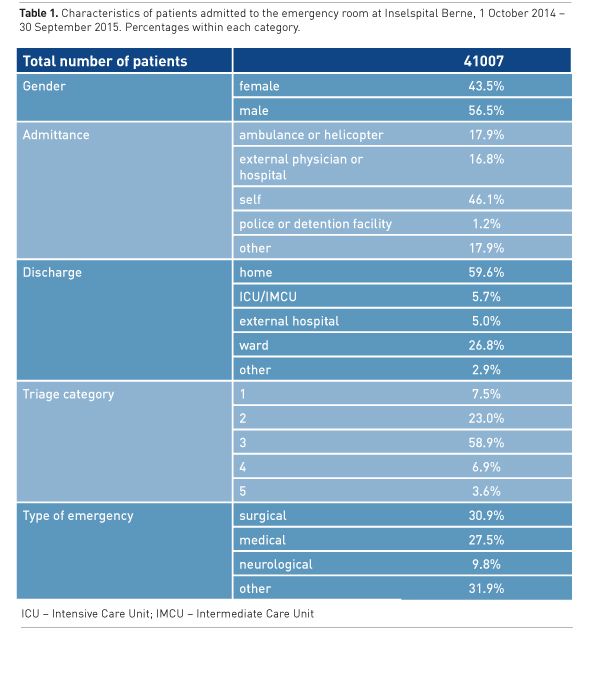

patients here (see Table 1), leading to a

relatively young population of patients (see

figure 1). This may further explain why caring

for hypothermic patients is comparatively common

in the Berne University emergency room.

Pre-hospital emergency service in the canton

of Berne is mainly provided by Rega and Air

Glacier (both providing a physician-staffed helicopter

rescue service) and the ‘Sanitätspolizei’

(translated as ‘rescue police’) on the ground.

The Sanitätspolizei staffs one car with an emergency

physician around the clock that can meet

the emergency medical service at the scene if needed, but paramedics in the usual rescue operation are fairly well

trained and are competent to provide a number of medical procedures

and treatments, including administering selected medications

or providing advanced airway management.

Once on their way to an emergency room, more seriously ill patients

are typically transported to one of the larger hospitals by the Sanitätspolizei.

Most patients in Swiss emergency departments, however,

are walk-in patients who present themselves (and most of the time

are treated and discharged: see Table 1). Around 60% of all patients

presenting to the emergency room in Berne are discharged home. Only

around 5.7% are admitted to the intensive or immediate care unit.

Intensive care specialists can typically expect a complete diagnostic

workup of patients transferred to the ICU, including collection of

microbial samples, calculated antibiotics, lumbar puncture and the

collection of procedural statements from all relevant disciplines. In

Berne, almost the only measure we omit in the emergency room is

inserting a central venous line into patients before admitting them

to the ICU, because doing so could limit the ICU's options for extended

haemodynamic monitoring, with either PICO catheters or a

pulmonary artery catheter, which is usually inserted together with

a central venous line.

Emergency Rooms

Most hospitals throughout Switzerland now operate as interdisciplinary

units, but there are still some older systems, in which patients are

separated along the lines of surgical care or internal medicine (Sanchez

et al. 2006). The emergency room at Berne University Hospital is an

interdisciplinary unit within the department of emergency medicine,

intensive care and anaesthesiology and sees all adult patients with an

interdisciplinary team. As in most other emergency rooms throughout

the country, patients are classified according to the urgency of their

treatment by specially trained nurses using a standardised triage model

(Hallas 2006; Hollimann et al. 2011). Urgent treatment (for around

7.5% of our patients) is usually provided within one of the three

shock rooms, while patients with minor complaints can be referred

to an integrated ‘fast lane’, staffed with one general practitioner from

8am to 10pm every day. Discharged patients can also be scheduled

to revisit within this fast lane concept.

Aside from patients who walk in or who are brought in through

an emergency service, the emergency room at Inselspital Berne sees

all non-planned patients referred to any of the specialities at the

University Hospital from an outside clinic. In total, we see more than

40,000 patients a year, with numbers continually rising for the last

five years. Around 18% of these patients are brought in by ambulance

or helicopter, slightly below half (46%) present themselves and the

remainder are referred to us from various sources, including external

hospitals, general practitioners, the police, psychiatric institutes or prisons (see Table 1). Those patients presented

by the police or referred from prisons are a

special feature of Berne, as the university hospital

here is the only one in Switzerland that

runs a specialised ward for detainees with all

medical care available.

Physician Education and Training

Current undergraduate teaching of emergency

medicine is rather sparse in Europe (Smith et

al. 2007). Education of physicians working in

emergency medicine in Switzerland is regulated

through the Swiss Society of Emergency and

Rescue Medicine (SSERM). It offers two types of

degrees, termed 'certificates of ability': one for

preclinical and one for clinical emergency medicine.

Both curricula are available online (sgnor.

ch/faehigkeitsausweise). While the certificate for

preclinical medicine is available to every physician

who has completed the three year curriculum,

the certificate for clinical emergency medicine

is only available once candidates have completed

residency and have obtained a degree in internal

medicine, surgery, anaesthesiology, intensive care,

orthopaedic surgery, traumatology or cardiology.

To obtain the certificate, one further needs to

participate in various courses (including Focused

Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST),

Advanced Trauma Life Support® (ATLS) facs.

org/quality%20programs/trauma/atls and Advanced

Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS)) and

complete an 18-month rotation in an accredited

emergency room. The curriculum is based on

the curriculum of the European Society of Emergency

Medicine (EUSEM), and the catalogue of

learning objectives is an adaptation of the English

Emergency Medicine specific learning objectives.

The degrees in clinical or preclinical emergency

medicine further require that the student passes a

final assessment. However, emergency medicine

is currently not available as a separate residency

training in Switzerland (Osterwalder 1998), and

the two certificates of ability do not substitute for

a residency programme, but may be completed

as part of a residency training. Maintenance of

certification requires physicians in Switzerland

to obtain a predefined number of credits for

continuous education activities, but currently

does not involve reassessments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Meret Ricklin,

PhD and Sabina Uttiger, both from the Department

of Emergency Medicine at Inselspital Berne,

for providing data for this article.

See Also:

Critical Care in the Emergency Department

Bundesamt für Statistik (2015) Aktuellste provisorische

Monats- und Quartalsdaten. Bevölkerungsstand und -struktur – Indikatoren. [Accessed: 30 October 2015] Available from

bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/01/02/blank/key/bevoelkerungsstand/01.html

Hallas P (2006) The effect of specialist treatment in

emergency medicine. A survey of current experiences. Scand J Trauma Resusc

Emerg Med, 14: 5–8.

Holliman CJ, Mulligan TM, Suter RE et al. (2011) The

efficacy and value of emergency medicine: a supportive literature review. Int J

Emerg Med, 4: 44.

OECD (2010) OECD

Gesundheitsdaten 2010. [Accessed: 28 August 2015] Available from

oecd.org/health/healthdata/

Osterwalder JJ (1998) Emergency Medicine in Switzerland. Ann

Emerg Med, 32(2): 243–7.

Sanchez B, Hirzel AH, Bingisser R et al. (2006) State of emergency medicine in Switzerland: a

national profile of emergency departments in 2006. Int J Emerg Med, 6(1): 23.

Smith CM, Perkins GD, Bullock I et al. (2007) Undergraduate

training in the care of the acutely ill patient: a literature review. Intensive

Care Med, 33(5): 901–7.

WHO (2010) The world health report 2000 - Health systems:

improving performance. [Accessed: 30 October 2015] Available from

who.int/whr/2000/en/

Wyss K, Lorenz N (2010) Decentralization and central and

regional coordination of health services: the case of Switzerland. Int J Health

Plann Manag, 15(2): 103–14.