HealthManagement, Volume 22 - Issue 4, 2022

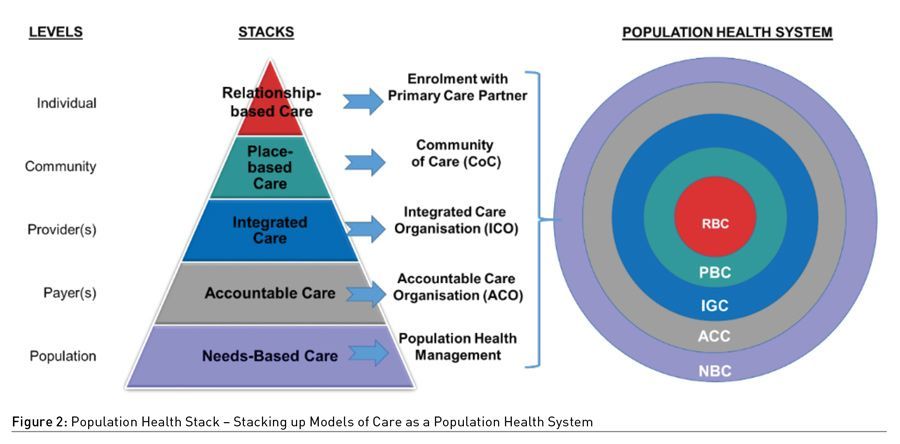

The Population Health Stack provides a systems language to illustrate the models of care that need to be developed at each level of a Population Health System. This allows us to flip the healthcare system and better address the new health needs of the population.

Key Points

- The traditional model of healthcare has become unsustainable. To address new needs of an ageing population, health systems are flipping healthcare and redesigning entire systems to move from volume-based to value-based incentives.

- To flip the health system to a Population Health System, three strategies to align, aggregate and anchor all actors in the system, namely the payer, provider and patient/resident helps health systems to achieve the triple aim.

- Five models of care have been identified and stacked to form the Population Health Stack.

- The Population Health Stack is supported by five key enablers, namely Care, Finance, Workforce, Digital and Data, and Engagement.

The traditional model of healthcare has been reactive and focused on centre-based resources needed to care for patients. This model of “patients going to where the care is, because that is where the money is”, has become unsustainable. This is particularly so for developed countries and health systems that are concurrently facing ageing populations, increasing burden of chronic diseases and years spent in poor health, rising healthcare costs and shortage of healthcare manpower. To address this, there is a global movement across health systems pivoting towards population health. Specifically, systems are flipping healthcare from siloed treatment to integrated prevention and management, and redesigning entire systems to move from volume-based to value-based incentives. Models where “the care and hence money follows the person” are also being promoted. The aim of the flipped model is to address the health of the population, bridge health and social care, and align payers, providers, and patients towards health. This is expected to achieve better alignment across the system, towards the triple aim of improving health outcomes, bending cost growth trajectories and provide care experiences that patients value.

While such broad change is deeply disruptive across payers, providers, and the population they serve, it is inevitable and necessary to ensure relevance in addressing needs for the population. For context, most health systems were designed for a time when populations were young and healthy. To ensure easy access when needed, policies and systems were designed to keep care affordable. Coupled with strong public health efforts to address social determinants of health (e.g. housing, education, communities, transport, the environment, and the economy) (Lovell and Bibby 2018), healthcare was a minor contributor (10%) to health (Bibby 2017), and little more than a repair shop and safety net. Healthcare utilisation and costs to the system would also generally be low in such young and healthy populations. However, in an ageing society with high living standards and ongoing efforts to address social determinants of health, the healthcare needs of the population are drastically different.

In a 2018 Singapore-based review, it highlighted financial security, employability, dementia, depression and social-emotional well-being and support, as issues faced by the elderly in the developed country that traditionally has a strong focus on public health (NPVC Knowledge and Insights Team 2017). In an ageing population, the new social drivers for health, like living with frailty, dementia, disabilities and social isolation are deeper and more complex than what most health systems were used to. As these very health systems (where hospitals act as safety nets for primary and community care models) were not designed to support ageing-in-place, this results in full hospitals, where discharges are constrained by the lack of suitable community-based options to help support residents with their needs. This is especially so, as frailty is a key driver for longer length of hospitalisation (Juma et al. 2016), and high mortality and institutionalisation within 12 months (Chong et al. 2018). Without flipping healthcare to population health, it is envisioned that hospitals (the most expensive healthcare setting) will be burdened with significant challenges in managing complexity, acuity, and frailty, resulting in unsustainable health systems.

Triple Strategy Towards Triple Aim

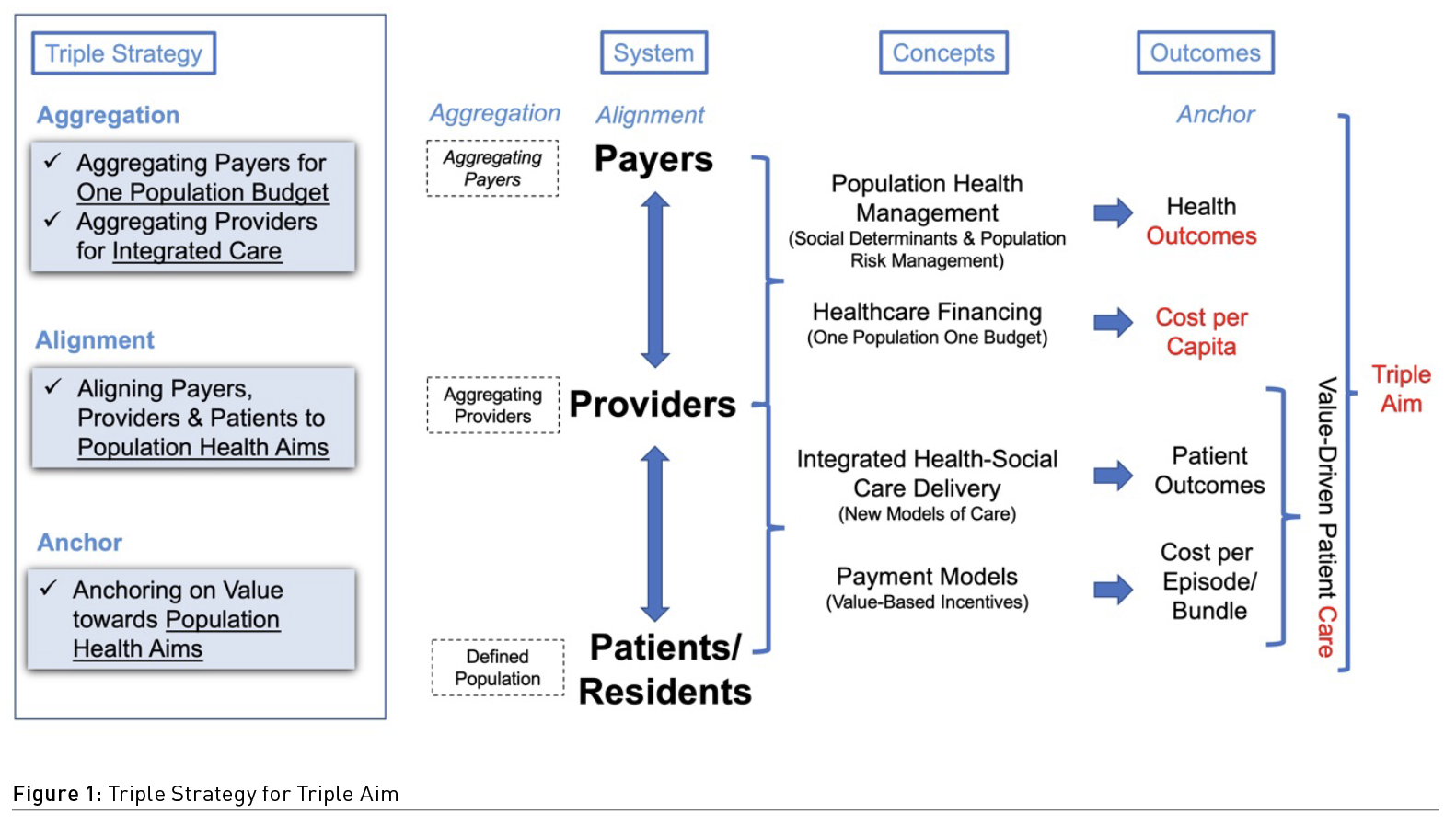

To flip the health system to a Population Health System, there is a need to Align, Aggregate and Anchor all actors in the system, namely the payer, provider and patient/resident. This triple strategy in re-designing the health system incentivises the behaviours of all actors towards health, reduces the fragmentation, and provides stackable value across the system. With alignment, the system encourages health-seeking behaviours with shared agreement across actors on care goals and payments. In aggregating budgets across payers and integrating care amongst providers, the high inefficiencies of today’s fragmented budgets and healthcare systems can be reduced with a one budget, one system, and one population approach. In anchoring care on value, it provides a universal language across the system from value-based patient care delivery to the triple aim of population health (Berwick et al. 2008).

In rolling out the triple strategy, there are four concepts to aggregate actors, achieve alignment and anchor on value. Firstly, between Payers and Providers, the Population Health Management looks at risks, needs and interventions which allows us to manage population health risk and achieve population health outcomes. It is supported by a Healthcare Financing to achieve one budget for the population served. Next, amongst Providers across the system, an Integrated Health and Social Care Delivery seeks to join up care. Lastly, this is accompanied by Payment Models that incentivise providers and patients towards shared goals. Together, these four concepts drive value for the population towards the triple aim of population health outcomes, care experience, and cost per capita (Figure 1).

Stacking Up Care in a Population Health System

Much has been written about health systems that are focusing on improving population health, through the development of integrated care and financing models (Akderwick et al. 2015). To integrate health-social care delivery for a population health system, five models of care were selected to form the Population Health Stack; the selected care models must work in tandem at different levels of the system to drive population health, while caring for the individual resident (Ham 2018). The use of a “stack diagram” for a population health system seeks to illustrate how care of the individual eventually stacks up to the health of the population (Figure 2). This provides clarity on how the different care models can be planned and organised across the different levels of the health system to achieve the triple aim.

At the top of the stack is the Relationship-Based Care (RBC) model. The RBC model describes the longitudinal care relationship between the resident and his/her primary care provider. The model empowers the resident who chooses to be enrolled in the relationship, to own his or her health. The primary care provider would then advise the resident to co-create a care plan that would strongly feature preventive health elements. This close relationship with a primary care provider, is expected to enable each resident to better understand his or her health profile with periodic reviews, set care personalised goals, and navigate the co-created care plan that is jointly agreed upon.

Surrounding the resident and primary care provider, is the Place-Based Care (PBC) model. The PBC model seeks to build partnerships with health and social care partners, into a geographical-based Community of Care (CoC) to support the health and social care needs of the local residents in a defined geographical area (approximately serving a few thousand residents). This approach ensures that care is localised to the needs of the residents at a neighbourhood level, and the availability of programmes offered by local health and social care partners.

The Integrated Care (IGC) model adopts a life-journey approach to design programmes that join up care for residents. With common features like preventive health, pre-disease, to end-of-life care, and the use of disease management, case management and care coordination enshrined in all programmes, the resulting integrated care programmes are cross-setting and drives the triple aim for sub-populations or disease-based cohorts. These integrated care programmes are supported by an Integrated Care Organisation (ICO) that serves as a network of providers (or an integrated care provider) that sees to the care needs of the residents (approximately 250 thousand to one million residents).

Integrated Care is best supported by an Accountable Care (ACC) model. In the ACC model, an Accountable Care Organisation (ACO) receives a budget for the care of a defined population (approximately one and a half to two million residents), and is held accountable for the health outcomes for that population. As the ACO is able to aggregate budgets at a much wider level (e.g. health and social care), it can achieve better alignment of the provider(s) to the payer(s) through a “one budget one population” approach. In this one budget approach, the ACC model would work with different financing models, from tax-based subvention to insurance models, to aggregate payers across the system. Downstream, the model allows providers to focus on the most appropriate integrated care, and promotes the use of value-based patient and provider payments to ensure the shift away from a fee for service and episodic care approach.

The base of the population health stack is a model that identifies the health risks of a defined population, translates that to needs, and designs resources and interventions that are targeted for each segment. This Needs-Based Care (NBC) model is the basis of population health management and underlies the development of a population health system. It shifts the focus upstream to look at needs and sets out the goals of the system aligned with the triple aim. With more weight given to effective risk adjustments in healthcare, several methods have been developed and implemented. These models range from simple models based on demographic characteristics (e.g. age and gender) to sophisticated models like the Johns-Hopkins Associated Clinical Groupings (ACG) and Patient Needs Groups (PNG) that take into account risk factors such as pharmaceutical or diagnoses (The Johns Hopkins University 2022; Stuch et al. 2022). Through these methods of identifying risks and needs, it helps health system administrators’ better plan resources.

Collectively, the Population Health Stack provides a systems language to illustrate the models of care that need to be developed at each level of a Population Health System. It enables clarity in planning and coordination, so as not to be at cross-purpose in transforming the healthcare system into a population health system.

Key Enablers for Transformation Towards a Population Health System

Beyond the models of care, there are five key enablers to successfully flip healthcare towards a population health system. They are: Care, Finance, Workforce, Digital and Data, and Engagement. In Care Transformation, the required shift is from a largely linear approach, to a complex-adaptive approach in redesigning care beyond the centre-based care settings, into the community.

Redesigning care requires an integrated box of tools from lean healthcare, design thinking, and organisational development. Lean is Left-Brain and focuses on reducing waste and optimising processes. Design thinking is Right-Brain which looks at ethnography to understand behaviours and interactions. Organisational development is the Brain Stem and it enables a deep learning cycle to build organisational health across the system to enable health and social change. In redesigning care, a whole-brain approach is needed.

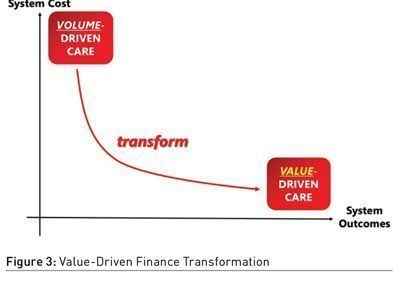

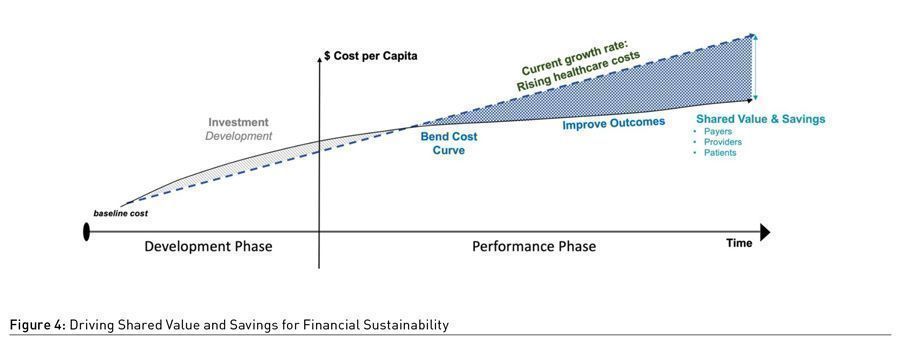

Finance Transformation seeks to align financing and payment models to achieve best system outcomes at a sustainable cost to the system (Figure 3). Value-based healthcare provides a universal language from the technical value of an episode of care to the triple aim of Population Health (Gray 2017). In financing models, capitation is a strong lever to drive value-based outcomes on a per resident basis, and risk pooling on a per capita basis. In payment models, value-based payment models and incentives for enrolees, can align residents and providers to health outcomes. At the system level, shared value contracts allow for shared savings across all actors in a population health system (Figure 4).

Workforce Transformation is key to scale and sustain a Population Health System. The redesign of jobs for healthcare professionals extends from individual job redesign, to team-based job redesign, trans-disciplinary job redesign to digitally enabled job redesign (Soh et al. 2021). The current “many (providers) to one (patient)” workforce model at hospitals pivots to a “one (provider) to many (residents)” workforce model in the community. This is enabled by introducing trans-disciplinary roles and the use of digital technologies to enable care to be delivered anytime, anywhere.

Digital and Data Transformation has a triple strategy of data, tools, and records. First, a population health registry with a health-social data analytics infrastructure. Second, Business to Business to Customer (B2B2C) digitalisation tools with a resident relationship management system. These tools can allow for care coordination and social prescribing with health and social care partners. Lastly, while the electronic medical records (EMR) system serves the provider and documents the transactions, a resident health records (RHR) system can empower residents to own their health, care goals and care plan. Such a RHR system can be built using a trusted digital wallet system that allow residents to share data with providers and stackable for citizenry functions.

Engagement underlies the need for payers, providers and residents to develop strong relationships across the population health system (Soh et al. 2020). For payers and providers, this is achieved through partnerships. For residents and caregivers, engagement drives activation for health. Activated residents own their health, are supported by their caregivers, communities and care providers.

Flipped Healthcare Towards a Population Health System: A Case Study of National Healthcare Group (Singapore) for Central and North Singapore

The Singapore health system is a mixed financing system that has achieved universal health coverage (Lee 2020). In 2021, the Ministry of Health (MOH) (Singapore) appointed the National Healthcare Group (NHG) (Singapore) as the regional health system for Central and North Singapore1, with an assigned population of 1.5 million Singapore residents.2 With an aim to flip healthcare and drive population health, in 2021, NHG reorganised and adopted a geographical based ACO-ICO structure, with NHG functioning as the ACO, and three zones; Central Health (CH); Yishun Health (YH); and Woodlands Health (WH), designated as ICOs that are in charge of working with their network of providers to care for their populations of approximately 250 thousand to one million.

Applying the strategies and population health stack described above, the following are some key highlights of NHG’s transformations (described using the population health stack framing):

- Relationship Based Care (RBC) – In conjunction with MOH’s (Singapore) Feb 2022 announcement to introduce resident enrolment to primary care providers (PCP) under Healthier SG, NHG has worked closely with the ministry and PCPs serving Central and North Singapore to promote enrolment. Efforts include ground up designing of care plan and financial incentive elements, two-way specialist referral operational workflows, and ensuring that private PCPs are supported by ICOs to ensure that the PCPs are equipped to retain and promote long lasting relationships with their residents. This is a major shift from the current processes, where residents could be lost to tertiary settings due to one-way referrals, or lack of incentives for residents to retain with their PCPs.

- Place-Based Care (PBC) – CoCs, a concept originally conceived by the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) (Singapore) was expanded and scaled up for Central and North Singapore, to support the local needs of the residents. As there was a very broad definition of what CoCs should be (which could be implemented by different stakeholders for their own needs), NHG developed a common definition and framework to enable a common working model and language to facilitate the conceptualisation and operationalisation of CoCs in Central and North Singapore. The NHG definition is “a network of service and strategic partners and activated residents, working collaboratively in the neighbourhood to deliver needs-based and place-based care”. The three features that each CoC would have are “Activating for Health”, where residents are empowered to own their health and build a caring community; “Ageing in Place”, for residents to live well in the community and avoid hospitalisation, and; “Anchoring care with partners” through place based partnerships, asset mapping and development and support health and social care.

- Integrated Care (IGC) – Traditionally, care delivery in Singapore is relatively institution-based, with pockets of integration efforts. Building on past and ongoing efforts in care integration, NHG brought together cross-sector inputs to develop the NHG River of Life concept for addressing care needs from Living Well, to Living with Illness to Hospital and Crisis Care, to Living with Frailty, and Leaving Well. All pathways will incorporate interventions and transitions across the segments of care that are collectively agreed by partner providers. For a start, NHG has decided on five key integrated care programmes that adopts the River of Life concept towards the triple aim of their respective sub-populations, namely: Metabolic Disease, Musculoskeletal, Chronic Respiratory and Mental Health conditions and Cancers. These were identified on the basis of most impact on population health outcomes and guided by the findings of the National Burden of Disease 2017 (Singapore). This is further enabled through the reorganisation of NHG into ICOs, where the planning and development of the sector are overseen by one network comprising of primary, tertiary and community care providers within the geographical area of influence.

- Accountable Care (ACC) – Furthering NHG’s reorganising as the ACO for Central and North Singapore, in 2022, MOH (Singapore) announced that they would be changing the public healthcare funding model from a largely fee for service to a capitation model. With this allocated per capita population budget, NHG will function as a sub-payer that assesses and manages our assigned population’s health risks. Beyond the most visible aggregation of the public sector subvention, NHG will also explore the possibility of aggregating other payers across the system, including that of residents themselves.

- Needs Based Care (NBC) – NHG has actively used data and digital tools in care delivery. As a next step, we will use shared population health management tools that allow population-level risk stratification and segmentation, and individual-level health and social assessment tools to design personalised care targeted at individual needs. Ongoing efforts include a regionalised population health registry that brings together residents healthcare records for comprehensive analysis, and meso and macro level planning.

Enablers

Care – NHG’s change management strategy for our ACO-ICO transformation is a phased, multi-year effort. Care Redesign is underpinned by a suite of innovation and improvement tools for change. NHG has adopted an extensive tool kit of lean, design-thinking and quality improvement tools to enable clinicians and administrators to come together to redesign care and adopt a value-based co-creation approach. In 2019, NHG’s subsidiary, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, opened the Ng Teng Fong Centre for Healthcare Innovation (CHI) to drive change through a systems approach, termed the Innovation Cycle. The Innovation Cycle comprises of Care Redesign, Technologies and Job Redesign in every innovation and improvement effort. This is underpinned by NHG Learning & Organisational Development’s KOLP framework (Knowledge-Organisation-Leadership-People) to build an organisational culture that catalyses and drives change. NHG aims to inculcate three key mindsets:

- Partner our Central North residents on this journey to Add Years of Healthy Life.

- We will do so by building an affordable health system that focuses beyond Illness to Wellness and delivers relationship-based care from cradle to grave for our residents.

- Collectively with our Staff and Partners, we strive to build a resilient community where residents are empowered to live well and age with dignity.

Finance - To enable the objectives and plans for our Care Transformation, NHG’s finance transformation for population health is premised on the principles of value-based funding and payment models, and alignment of stakeholders to achieve common goals through shared accountability. While capitation funding from MOH is a big step, the age-based adjustment model is best suited at an ACO level due to sufficient economies of scale. Hence, NHG is also embarking on a cross sector review and fine-tuning of funding to ICOs and payments to partner providers, to ensure system sustainability, while ensuring that providers are adequately compensated.

Workforce – To address the significant manpower challenges faced by the healthcare industry and in response to the evolving care models in the transformation towards a population health system, NHG embarked on a workforce transformation effort tied to its redesign of the health system. This was led by CHI, through co-learning with healthcare, industry and academic partners across Singapore and internationally. This co-learning network enables healthcare professionals and partners to bring their thoughts, their ideas and their passion, and turn possibilities into real world solutions, which empowers the healthcare workforce for the future. As a next step, NHG aims to bring together our partners to co-design and develop the community workforce of Central and North Singapore. The hospital adopts a many-to-one workforce model, whereas for sustainability and productivity, we need a one-to-many workforce model if we are to shift care into the community. This would be through the NHG Cares Institute (NCI), which is envisioned as a network of community, innovation and training partners who together can design the community health workforce for the future, and activate residents and their communities towards health.

Digital and Data – An imperative enabler, NHG aims to build a digital village populated with user-centric and data-centric micro-services or micro-applications that would serve the B2B2C (Business-to-Business-to-Consumer) needs of our residents and providers. To do so, NHG’s digitalisation efforts look to support four key shifts. First, from serving patients to serving all assigned residents. Second, from building patient stickiness to providers, to that of the community in a place and relationship-based care model. Third, beyond the institutional level to integrated network of care providers. Lastly, to shift residents from passive recipients of healthcare to empowered owners of their own health. This transformation focuses on key design principles of user-focused, stackable, asset-light digital solutions for population health delivery, supported by secured sharing verifiable and portable information. Current focuses include a population health registry, customer relationship management platforms for both residents and partner providers.

Engagement – The foundation of an effective and sustainable ACO and ICO begins with a shared vision and building trust among all players. To do this well, we have designed engagements across national, regional, community and individual levels. At the resident facing front, we have ongoing resident discovery sessions (for insights), and are committed to ensure that our efforts are appropriately targeted through branding, engagement channels and activities. Taking a step to simplify our branding, we will also bring all resident engagements and population health products under a single brand name. At the provider facing front, the engagements are three tiered. Relationship managers with individual partner providers; the creation of a strategic collective leadership council (POPCollect) with key partners, and a large scale Population Health Connect (POPConnect), an annual co-creation and community of practice of healthcare workers to develop a model of health and advance our Population Health movement in Central and North Singapore.

The NHG journey to flip healthcare towards population health is still in its early stages, and we would continuously evaluate the performance of our organisation as we advance into population health for our residents.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Alderwick H, Ham C, Buck D (2015) Population health systems, going beyond integrated care. The King’s Fund. Available from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/population-health-systems-kingsfund-feb15.pdf

Berwick DM, NolanTW, WhittingtonJ (2008) The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health affairs (Project Hope). 27(3):759–769.

BibbyJ (2017). Health care only accounts for 10% of a population’s health. The Health Foundation.Available from https://www.health.org.uk/blogs/health-care-only-accounts-for-10-of-a-population%E2%80%99s-health

Chong E, HoE, Baldevarona-Llego J et al. (2018) Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: Comparing Different Frailty Measures in Predicting Short- and Long-term Patient Outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 19(5):450–457.e3.

Gray M (2017) Value based healthcare. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 356:j437.

Ham C (2018) Making sense of integrated care systems, integrated care partnerships and accountable care organisations in the NHS in England. The King’s Fund. Available from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/making-sense-integrated-care-systems

JumaS, TaabazuingMM, Montero-Odasso M (2016) Clinical Frailty Scale in an Acute Medicine Unit: A Simple Tool That Predicts Length of Stay. Canadian geriatrics journal. 19(2):34-39.

LeeCE (2020). International Health Care System Profiles (Singapore). Available from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/singapore

LovellN, Bibby J (2018) What makes us healthy? An introduction to the social determinants of health. The Health Foundation. Available from https://www.health.org.uk/publications/what-makes-us-healthy

NPVC Knowledge &Insights Team (2017) Report on Issues Faced by the Elderly in Singapore. National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre (Singapore). Available from https://cityofgood.sg/resources/report-on-issues-faced-by-the-elderly-in-singapore/

StuchS, Barrett J, ThompsonA (2022) An Introduction to Patient Needs Groups.Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Soh E, Lim JM, HoiSY et al. (2021) Healthcare Worker 4.0: Redesigning Jobs for the Future. HealthManagement.org The Journal. 21(4):193-198.Available from https://healthmanagement.org/c/hospital/issuearticle/healthcare-worker-4-0-redesigning-jobs-for-the-future

SohE, LeeD, LohSC et al. (2020)A Hospital Without Walls. HealthManagement.org The Journal. 20(8):596-601.Available from https://healthmanagement.org/c/healthmanagement/issuearticle/building-a-hospital-without-walls

The Johns Hopkins University, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Johns Hopkins Health System (2022) The Johns Hopkins ACG System: About the ACG Systems. Available from https://www.hopkinsacg.org/about-the-acg-system/