A false-positive screening for breast cancer may reduce the likelihood of a woman returning for her next planned mammogram if her prior test was within one and three years, a study at the University of North Carolina has found.

Interestingly, however, the findings also suggest that a woman has a higher likelihood to return if her prior mammogram was more than three years prior, with a reduced level of psychological distress associated to the screening.

The findings from a University of North Carolina Comprehensive Cancer Center study (abstract #2585) were presented at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting in New Orleans.

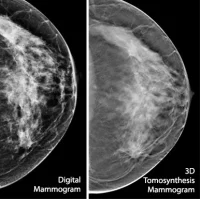

A false-positive result is when a mammogram finds something that looks like cancer, but it is later determined to be normal.

A woman who undergoes annual breast cancer screening with mammography has, on average, a 61 percent chance of receiving a false-positive mammogram after ten screenings, said Louise Henderson, PhD, a UNC Lineberger member and an assistant professor of radiology at the UNC School of Medicine, and the paper’s senior author. For women screened every two years, the chance of a false-positive is 42 percent after ten mammograms.

“False positives can cause anxiety and stress, and it often means additional costs and time off from work,” Henderson said. “There is the potential for these factors to influence the subsequent screening behaviour of women. It’s important to remember that breast cancer screening works best when guidelines are followed and women get screened on schedule.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Mammography Quality Standards Act and Programme estimates that 39 million mammography procedures are performed in the United States every year.

Previous studies have shown mixed results of whether women are adherent to screening guidelines after receiving a false-positive result, Henderson said.

In their study, researchers examined Carolina Mammography Registry screening data from 2004-2009 linked with private insurance data for 14,071 women aged 40 to 64 years.

The study drew on UNC Lineberger’s Integrated Cancer Information Surveillance System (ICISS), a research tool that contains details on cancer cases across North Carolina, linked to health claims data for 5.5 million people insured by Medicare, Medicaid, State Employees’ Health Insurance, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina.

They looked at whether women went on to get a mammogram within nine months to two years of receiving a false-positive result.

They found that 81.8 per cent of women went on to get a mammogram within 24 months if they had a false-positive finding. That was compared to 84.2 per cent of women who had a true negative result.

In terms of relative risk, women who received a false-positive result were 23 per cent less likely than women who had a true-negative result to get another mammogram within two years if their prior mammogram was within one to three years of the false positive exam.

In contrast, women with a false-positive result who had their prior mammogram more than three years earlier were 80 percent more likely to have a screening mammogram within two years than women who received a true negative result.

“We found that a false-positive result may reduce the likelihood of a woman returning for her next planned screening mammogram if her prior mammogram was within one to three years,” Henderson said. “But it may increase her likelihood to return if her most recent mammogram was more than three years prior.”

The study was supported by a UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Developmental Award and grants from the U.S. National Cancer Institute.