ICU Management & Practice, Volume 17 - Issue 3, 2017

Outlines some basic considerations for ICU providers interested in incorporating animals into care programmes.

Animals are being introduced into hospital settings in ever-increasing numbers. Emerging literature suggests that incorporating trained animals to assist with medical care and rehabilitation therapies can promote patient engagement, reduce emotional distress and relieve some aspects of physiologic burden. Below, we outline some basic considerations for ICU providers interested in incorporating animals into care programmes.

Why include animals in the ICU?

An increasing number of patients are surviving critical illness, resulting in increased attention to understanding patients’ experience while in the intensive care unit (ICU). As a result, new insights have been gained regarding enhancing the ICU environment, including “humanizing”’ the ICU (Brown et al. 2016). In examining ways to improve the patient experience, some healthcare facilities integrate animal therapy as a means to support patients’ mood (Bernabei et al. 2013; Hoffmann et al. 2009), increase engagement in rehabilitation therapies (Muñoz Lasa et al. 2011) and reduce aspects of physiologic symptoms (e.g., pain) (Halm 2008). Animal therapy has been used in a wide range of patient groups ranging from paediatrics to geriatrics. Publications focused on animals in the ICU setting are scant, with anecdotes suggesting that animal presence in the ICU is beneficial to patients (Lee and Higgins 2010).

What are animal-assisted activity and animal-assisted therapy?

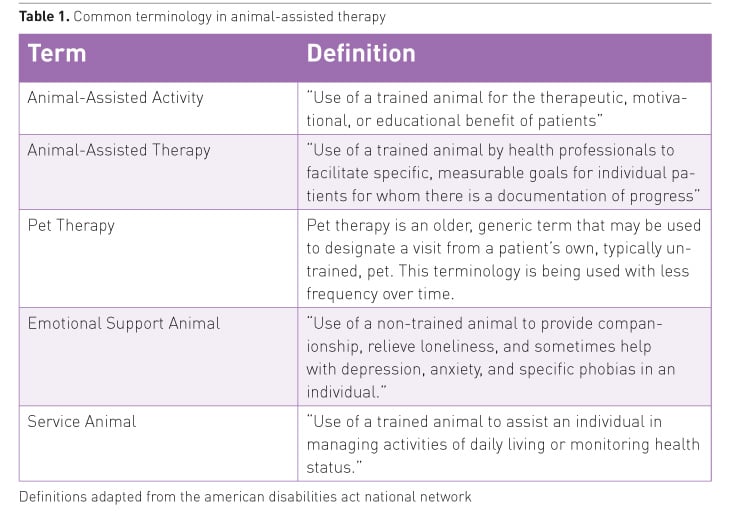

When animals and their handlers (therapy animal teams) are incorporated into care settings, they may serve in several roles, with specified terminology used to describe each role. First, animal-assisted activity (AAA) is a term referring to the use of trained animals for the therapeutic, motivational or educational benefit of patients (Delta Society 2006) (Table 1, Figure 1). Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) refers to the practice of rehabilitation therapists working with specialty trained animals to facilitate specific, measurable goals for individual patients for whom there is documentation of progress (Kruger et al. 2006). Use of the term “pet therapy” may be best reserved for instances when patients’ own pets are involved for purposes of emotional support. Although dogs are most commonly employed in hospital settings, other animals used in AAA/AAT have included dolphins, cows, birds, horses, fish, llamas and cats (Morrison 2007).

The above terms should not be confused with a visit from a “service animal,” “emotional support animal,” or the patient’s pet (Brennan 2014; Table 1). A visit by such animals needs to be a well-considered decision by the clinical team, with input from legal and infection control services within the facility and review of any facility-specific policy.

When should animals be

incorporated into a treatment plan?

Literature regarding the benefits of AAA/ AAT provides some guidance about which critically ill patients may benefit most. Several studies have documented the effectiveness of AAA/AAT in patients with mental health symptoms, including symptoms of depression, anxiety and loneliness (Wu et al. 2002; Banks and Banks 2002). For example, dog visitation in a paediatric cardiac inpatient setting was associated with both children and parents reporting reduced levels of stress and higher levels of positive affect after a 10-20 minute visit. Similarly, AAA/AAT has increased patient satisfaction among trauma survivors (Stevens et al. 2017). Consequently, ICU clinicians may consider prioritizing AAA/AAT to patients with hospital-related demoralisation and high anxiety.

A favourite patient experience at our institution is that of a paediatric ICU patient, receiving extracorporeal support, with a length of stay >600 days. She missed her home, a farm several hours from the hospital. In particular, she missed her cow, Pantene. Consequently, family members and ICU staff coordinated an effort to bring her cow to the hospital courtyard so that she could pet her and have a connection to home. The joy of that moment, experienced by that patient (and staff), has a lasting positive effect.

You might also like: Pet Therapy For Hospital Employee Stress

Furthermore, AAT may increase patient engagement and improve performance during rehabilitation sessions (Muñoz Lasa et al. 2011). Specifically, patients with known difficulties participating in rehabilitation and mobility interventions may be good candidates for AAT. Numerous studies report an association between AAA/AAT and improved symptoms including pain (Halm 2008, Morrison 2007), making ICU patients with persistently high levels of pain potential candidates. Finally, AAA/AAT has been associated with improved learning among people with acquired cognitive disabilities (Bernabei et al. 2013) which might be beneficial in the ICU setting given high rates of cognitive changes, such as delirium.

Are there risks or contraindications in AAA/AAT?

There are some risks and contraindications to AAA/AAT (Brodie et al. 2002). Some patients may be allergic to pet dander or averse to animal visits. Asking patients and families about their level of interest is important to ensure that only those patients who welcome AAA/AAT receive visits. Institutions remain vigilant to the risk of infectious diseases. Working with institutional infection control programmes will help ensure that both patients and animals stay healthy. Such programmes can guide teams toward preventing zoonotic infection (i.e., transmitting disease from animal to human), reducing risk of fomite contamination with an animal carrying a pathogen from one patient to another patient on fur, leash or vest. In our institution, these issues have resulted in guidelines that include bathing and grooming requirements for animals prior to coming to the hospital, as well as handwashing or sanitising before and after each patient visit. Moreover, dog licks are prohibited at our institution, as well as visits from animals on raw diets. For patients on contact precautions or isolation, infection control practitioners and the clinical team can make case-by-case decisions regarding the risks and benefits to the patient and therapy animal.

How can animal-assisted activity be built into an existing team?

When considering an AAA programme, an integral first step is to find a champion who is passionate about creating this culture change. This person is typically a key stakeholder, consistently present in the organisation, who has access to institutional resources and ability to influence systemic change. Physicians, rehabilitation therapists, nurse educators and managers, and social workers are all potential champions. AAT programmes require rehabilitation therapist involvement as they utilise the therapy animal team as a modality for patient treatment.

Identify goals

A next important step is to identify the goals of the AAA/AAT programme. If these goals are well circumscribed, the likelihood that the programme (usually a scarce resource in early stages) will reach patients in a way that maximises benefits. Programmes that are implemented without clear patient and programme goals will have a more difficult time documenting and highlighting the improvement in patient-related outcomes.

Protocol/ policy

We also suggest partnering with other key stakeholders to build a protocol/policy that will serve to create a structure for the programme, limit risk to patients and animal therapy teams, and support ongoing programme evaluation. Important disciplines involved in protocol development include physical medicine and rehabilitation, nursing, infection control, risk management and volunteer services. A protocol/policy should include the following:

- Responsibility of all involved parties: programme coordinator,

animal team (handler), volunteer office, patient care team, infection control

practitioner

- Procedure:how and where animals can visit, how long animals can

visit, policy for photos, structure of the animal visit, disclosure of

potential risks to the patient and animal therapy team

- Reportable conditions and events:animal bites or scratches,

patient harm to animal or handler, zoonosis or transmission of organism to

therapy animal, unexpected animal death

- Documentation of visits in the patient medical record and in the unit

records: when, what and who should record

- Programme evaluation: ways to effectively measure the frequency and

effectiveness of the visits

For assistance in building a protocol, some helpful resources include a set of guidelines for animal-assisted intervention to minimise spread of infectious disease (Lefebvre et al. 2008), references that enhance learning about standards of practice (e.g. Delta Society 2003), and guides that reinforce the definitions of AAA/AAT (e.g. Brennan 2014).

Resources

Once an AAA/AAT programme has a champion and identified goals, the next step is to find an organisation experienced in training therapy animal teams. Valuable resources that help with vetting and training of animal therapy teams include organisations such as Pet Partners, Inc. (petpartners.org), Therapy Dogs International, Inc., The American Kennel Club (akc.org/events/title-recognitionprogram/ therapy) and Assistance Dogs International (assistancedogsinternational.org). Socialisation, obedience and temperament assessment are all components of the certification process. Reviewing these resources can help handlers and institutions find a training group that is local, experienced, and free from commercial bias.

Conclusion

Although limited, early evidence suggests that AAA/AAT is a therapeutic activity that has potential to reduce stress and suffering in ICU patients. Carefully matching well-trained animal teams to patients may result in reduced emotional stress, increased patient satisfaction, and ease of physiological burden. When an AAA/AAT programme has a passionate champion and a strong institutional protocol, it can maximise success and benefit.

Abbreviations

AAA animal-assisted activity

AAT animal-assisted-therapy

ICU intensive care unit

Tweets

References:

Banks MR, Banks WA (2002) The effects of animal-assisted therapy on loneliness in an elderly population in long-term care facilities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 57(7): M428-32.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12084804

Bernabei V, De Ronchi D, La Ferla T et al. (2013) Animal-assisted interventions for elderly patients affected by dementia or psychiatric disorders: a review. J Psychiatr Res, 47(6): 762-73.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23369337

Brennan J (2014) Service animals and emotional support animals: where are they allowed and under what conditions? Houston, TX: Southwest ADA Center. [Accessed: 3 July 2017] Available from adata.org/publication/service-animals-booklet

Brodie SJ, Biley FC, Shewring M (2002) An exploration of the potential risks associated with using pet therapy in healthcare settings. J Clin Nurs, 11(4): 444-56.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12100640

Brown SM, Beesley SJ, Hopkins RO (2016) Humanizing intensive care: theory, evidence, and possibilities. In: Vincent, JL, ed. Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2016. Cham: Springer International, pp. 405-20.

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-27349-5/page/2

Delta Society (2003) Standards of practice for animal-assisted activities and therapy. Renton, WA: Delta Society.

Delta Society 2006 - should this be Delta Society (2005) Introduction to animal assisted activities and therapies. Renton, WA: Delta Society.

Halm MA (2008) The healing power of the human-animal connection. Am J Crit Care, 17(4): 373-6.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18593837

Hoffmann AO, Lee AH, Wertenauer F et al. (2009) Dog-assisted intervention significantly reduces anxiety in hospitalized patients with major depression. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 1(3), pp. 145-148.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876382009000419

Kruger KA, Serpell JA (2006) Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: definitions and theoretical foundations. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice, 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, pp. 21-38.

https://www.elsevier.com/books/handbook-on-animal-assisted-therapy/fine/978-0-12-369484-3

Lee D, Higgins PA (2010) Adjunctive therapies for the chronically critically ill. AACN Adv Crit Care, 21(1), pp. 92-106.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20118708

Lefebvre SL, Golab GC, Christensen E et al. (2008) Guidelines for animal-assisted interventions in health care facilities. Am J Infect Control, 36(2): 78-85.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18313508

Morrison ML (2007) Health benefits of animal-assisted interventions. Complementary health practice review, 12(1): 51-62.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1533210107302397

Muñoz Lasa SM, Ferriero G, Brigatti E et al. (2011) Animal-assisted interventions in internal and rehabilitation medicine: a review of the recent literature. Panminerva Med, 53(2), pp. 129-136.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21659977

Stevens P, Kepros JP, Mosher BD (2017) Use of a dog visitation program to improve patient satisfaction in trauma patients. Journal Trauma Nurs, 24(2): 97-101.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28272182

Wu AS, Niedra R, Pendergast L et al. (2002) Acceptability and impact of pet visitation on a pediatric cardiology inpatient unit. J Pediatr Nurs, 17(5): 354-62.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12395303