The Compassionate Care Initiative at the University of Virginia

Compassionate care is essential to provide quality care and support a resilient workforce. The Compassionate Care Initiative offers programmes that support resilience for critical care providers and hospital leadership.

“Compassion is central to being fully human” (Halifax 2018); it is good for one’s health as it can improve one’s outlook on life, decrease risk for depression and reduce perceived stress (Neff 2016; Klimecki et al. 2012). Though challenging to quantify, compassion is crucial to quality care. Fast-paced work areas with critically ill patients demand focus, the ability to work with a team for long hours and the capacity to bounce back when results are not optimal. From unit staff to hospital leadership, the demands of patient care are taxing on everyone. Families and patients not only expect wise nurses, physicians and administrators, but they also expect—and deserve—compassionate care while in the hospital. Far too often, compassion falls to the wayside of the autobahn of technological and surgical advances. When compassion dissipates however, patient satisfaction can decrease (Newcomb et al. 2017). What is worse, with less perceived compassion, staff face the increased risk of burnout and the negative sequelae that are associated with it—depression, lost work hours, suicide (Dev et al. 2018). Thus compassion is both central, and crucial. It is a practice for others and the self.

Since 2009, the Compassionate Care Initiative (CCI) at the University of Virginia (UVA) has developed and implemented programming with a focus on resilience and compassion. Housed in UVA’s School of Nursing, the CCI works closely with hospital administration and clinicians at the UVA Health System; faculty and staff at the university; and of course, students. Its impacts are longstanding and its methods of outreach are feasible and inexpensive. Its mission is to “cultivate a resilient and compassionate healthcare workforce—locally, regionally, and nationally— through innovative educational and experiential programs” (cci.nursing.virginia.edu). This article will share the conceptual model of the CCI and then focus on two key elements of the CCI’s work that have shaped compassionate care in critical care settings.

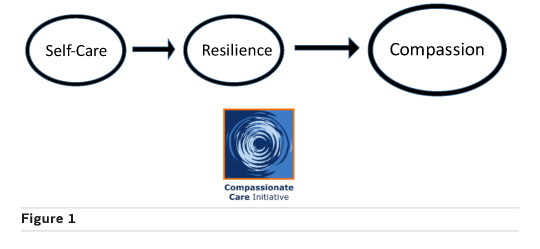

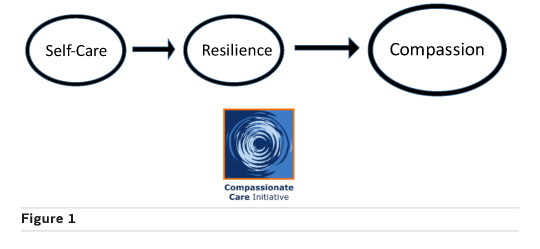

Conceptual model

The cultivation of compassion arises through the practice first and foremost of self-care (Alkema et al. 2012). The CCI defines self-care as a broad spectrum of actions that an individual or group can take that are both prosocial and effective in improving physical or mental health. Self-care is broad. A growing body of evidence supports yoga, meditation, prayer and exercise as forms of self-care. In 2016, the CCI surveyed its nurses to learn about their self-care practices. Results suggested that self-care can be defined by the person who practises it (some considered cleaning a form of self-care as well as gardening or preparing food for loved ones). What mattered most was the intention behind the action that determined whether it was self-care or not (Cunningham et al. under review). Self-care practices enhance the ability for a care provider or leader to face adversity and essentially bounce back so as to be their best performing self in a professional setting. Thus self-care improves resilience (Shapiro et al. 2007). We propose that a more resilient workforce, one that is able to face challenging situations, make the changes needed to ameliorate the root causes of those situations and remain attuned to the needs of the present moment (moment by moment), will be able to provide more compassionate care. Some evidence suggests that compassion training as it is related to mindfulness can improve compassion, presence and resilience (Engen and Singer 2015). The CCI conceptual model (Figure 1) is therefore simple and direct.

Clinical ambassadors

Since its inception, the CCI has offered a meeting space for its clinical and faculty ambassador programme. We have worked with chief nursing officers, unit managers and other top-level leaders in addition to staff nurses and physicians. The goal of the ambassador programme has been to offer a place for colleagues to meet monthly and discuss resilience-based interventions that can be rolled out on hospital units. The ambassadors, who volunteer their time, work as a think-tank that examines ways to build resilience and compassion in our health system. The CCI provides a small amount of funding in the form of grants to further develop the programmes. Of a long list of interventions that have been started at a very “grassroots” level and that have moved upwards into the top levels of leadership, two profound projects have arisen and will be discussed next.

“The Pause” is an intervention developed by an emergency department nurse (Bartels 2014) that is now used in many intensive care unit (ICU) settings at the UVA Health System, various states across the United States and also in Australia, South Africa and Ireland (Ducar et al. under review). This practice occurs when a patient has an untimely death in a hospital setting—most frequently in ICU or emergency settings. Any caregiver in the room, nurse, physician, chaplain, social worker or cleaning staff, has the opportunity to ask the group to pause. They take 45 seconds of silence and introduce the silence by asking everyone to recognise the life in front of them that just ended as well as to recognise the combined effort of the team that tried to save the patient’s life. The practice is simple and profound (thepause.me).

Another initiative that was inspired from the CCI ambassador’s programme was devised by two paediatric nurses. They recognised that in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) settings there was not a physical space where staff could retreat safely to process the effects of untoward events. There were “quiet rooms” on the units, but those rooms were often in use by family members grieving or receiving bad news. These nurses petitioned hospital leadership and established funding to build a “resiliency room” that sits between the PICU and NICU. This small room is accessible only by the swipe of an ID card, thus only hospital staff can access it. In the room there is a couch, meditation cushions, contemplative reading material, tissues and a mirror. This space, very close to the patient care areas of the ICUs has been designated as a safe space for staff members to take some quiet time or alone time after a sentinel event. The proximity to the units allows staff members to step away for short periods of time without having to leave the unit and their other patients. Since the building of the ICU resilience room, other units in the UVA Health System have built their own spaces for staff resilience.

These two exemplars illustrate the collective support that the CCI gives to clinicians in its affiliated health system. What’s more, these examples show the “grassroots” nature of the CCI’s support. These initiatives have gotten supportive attention from hospital leadership to the extent that the CCI now consults with leaders in the UVA Health System on systems-wide self-care and resilience practices.

Resilience retreats

Another hallmark of the CCI is its resilience retreat programme. Based on structured mindfulness practices, such as mindful movement, walking meditation, sitting meditation, mindful eating and listening practices, the CCI provides half-day or full-day retreats for learners and practitioners. The retreats are offered free to all participants and they are facilitated by trained mindfulness and yoga instructors. Funding for these retreats comes from the UVA School of Nursing, alumni donors and also from the UVA Health System. These retreats are inclusive and they offer staff members the opportunity to interact with each other outside of the hospital setting. The retreats are held at a local farm where staff members not only can participate in mindfulness-based activities, but they can also spend time out in nature. Retreats such as these are thought to reduce stress, improve working relationships and improve resilience (Henry 2014; Aycock and Boyle 2009). The CCI offers unit-based retreats to any unit on the hospital, including leadership units (such as nurse managers) as a resilience practice. Continuing education is offered as well.

Culture change

Though a more resilient workforce is essential when it comes to staffing and safe, quality care, it must be recognised that making staff more resilient is by no means a single solution to deeper structural issues in healthcare. It is important to train caregivers with skills so that they can bounce back in the face of adversity. It is equally as important to train caregivers with the skills to make systemic changes so that work related stressors may, over time, become less poignant hindrances to quality care. Research on burnout suggests that it is systems issues, technology concerns, long work hours and staffing issues that make caregivers less resilient (Rushton et al. 2015; Ehrenfeld and Wanderer 2018; Shanefelt et al. 2012). The CCI recognises that most self-care and resilience practices can be started at the individual level and they can have essentially low or no financial costs. We also recognise that self-care must not stay at the individual level if we are to see changes in workplace culture and a more resilient workforce. Unit and hospital leadership must also adapt resilience practise and support staff with time and finances so that they may practise self-care and resilience. If leadership does not also recognise and embrace the importance of self-care and resilience, then individualised efforts will not sustain themselves, and the potential of improved quality of care and improved staffing will not be met. A colleague at the UVA Health System made this point clear when he said that if hospital leadership does not embrace and practise self-care and resilience, then talking about it is nothing more than lip-service, and resilience will be utterly meaningless.

Conclusion

The Compassionate Care Initiative is a multi-faceted organisation that strives to improve resilience in healthcare settings. From individualised approaches to self-care to strategic planning with hospital leadership, the CCI recognises that quality and compassionate care can arise from a resilient workforce. Resilience is complex and compassion is hard to measure, but we assert that these two tools are essential in the care of other human beings. CCI programmes are designed to meet specific needs of caregivers and the units within which they work so that they may be prepared to meet ever-changing challenges that arise when treating critically ill patients in often critically distressed health systems.