According to a new study published in Radiology, a combination of different imaging techniques can find structural abnormalities in the brains of people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). The findings suggest a potential for diagnosing and treating this condition.

People with CFS suffer from profound fatigue and a brain fog that does not improve with bed rest. These symptoms last at least six months. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly one million adults and children in the United States are affected by this condition. Diagnosing the disease is fairly complex and involves ruling out many other conditions. To date, there is no stand-alone test to diagnose CFS.

“This is a very common and debilitating disease,” said the study's lead author, Michael M. Zeineh, MD, PhD, assistant professor of radiology at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. “It’s very frustrating for patients, because they feel tired and are experiencing difficulty thinking, and the science has yet to determine what has gone wrong.”

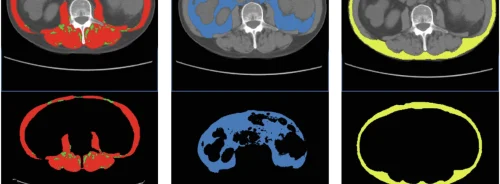

Dr. Zeineh, along with a Stanford CFS and infectious disease expert, Jose G. Montoya, MD, performed MRI scans on 15 CFS patients and 14 age and gender matched controls. Three different MRI techniques were applied, including: volumetric analysis to measure the size of different compartments of the brain; diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to assess the integrity of the signal-carrying white matter tracts of the brain; and arterial spin labelling (ASL) to measure blood flow.

The results from the examinations showed that the CFS group had slightly lower white matter volume and abnormally high fractional anisotropy (FA) values. There were also abnormalities at two points in the brain that connect the right arcuate, and the cortex was thicker in CFS patients. Dr. Zeineh points out that the right anterior arcuate FA increased with disease severity in patients suffering from CFS. This also correlated with their fatigue. The findings suggest that FA at the right arcuate fasciculus could possibly serve as a biomarker for CFS and could help track the disease.

“This is the first study to look at white matter tracts in CFS and correlate them with cortical findings,” Dr. Zeineh said. “It’s not something you could see with conventional imaging.”

The technique shows significant promise as a diagnostic tool to identify people with CFS. The techniques that were used in the study were 80 percent accurate in detecting CFS. However, the findings need to be further expanded and future studies need to be conducted to understand the relationship between the structure of the brain and CFS.

Source: RSNA

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons