Introduction

Up to 85% of critical care patients may experience some form of delirium, but it can be very easily missed (Inouye et al. 2001; Page 2008) particularly in a very busy 24 bedded General Critical Care Unit that is also the regional centre for Trauma and neurosurgery. The unit admits both level 2 and 3 patients within the same clinical environment for critical care support following trauma, neurosurgical intervention, post-operative care after vascular, upper & lower gastro-intestinal, maxilla-facial or gynaecological surgery or where advanced respiratory, cardiovascular and renal support are required for the deteriorating patient.

Together with Lancashire and South Cumbria Critical Care Network (LSCCCN) as quality improvement link nurses our current aim is to reduce and implement change in regard to DELIRIUM within Critical Care. By focusing on improving sleep to reduce delirium we are adding to work previously conducted in our unit (Patel et al. 2014) which demonstrated sleep improvement with a multicomponent bundle.

Delirium

Delirium has been defined as an acute brain syndrome and as such should be recognised and treated as early as possible within the critical care environment (Page 2008). For patients who are suffering from delirium, any delusional thoughts or images are very real to them. In addition, unlike a dream, these images do not fade away but come and go continuously. We assess patients three times per 24 hours using the confusion assessment method (CAM-ICU) tool. Scoring patients at three different times throughout a 24 hour period enables clinicians to detect the fluctuating phases of delirium. Patients may experience hyperactive, hypoactive or mixed delirium behaviours. The CAM-ICU tool will determine whether at the time of testing the patient is either positive or negative for delirium. The interventions we currently use to try and reduce adverse effects of delirium include orientating patients to their surroundings and the use of agitation mitts for those who are pulling at intravenous, arterial or central lines. If all environmental initiatives have been exhausted then medications such as dexmedetomidine or haloperidol will be administered to ensure patient safety.

Environment

The environment of the Critical Care Unit can impact on patients becoming delirious. Upon our unit, there are few windows to enable natural light onto the unit, so it is difficult to create a sense of day and night. As the building structure of our unit cannot be changed, we decided to focus on what we as nurses can do to help reduce the incidence of delirium. We felt an effective way to do this was to assist our patients in achieving a better night’s sleep and feeling safe within the critical care environment.

The very nature of a close patient monitoring environment where care interventions are required around the clock impedes on establishing the difference between day and night. The need to admit patients or perform life-saving interventions at any time, day or night can and does impact on how well patients sleep at night. To compound this further is the constant alarming of monitors, ventilators and medication pumps which further impacts on a patient’s ability to achieve a sleep pattern which is therapeutic.

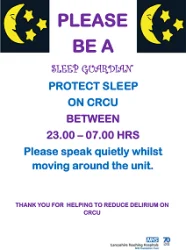

Within the NHS there are ‘Caldicott Guardians’ and teams who ‘SafeGuard’ patients, so we thought why are there not ‘SLEEP GUARDIANS,’ to protect a patient's time to sleep, renew and repair.

The role of the SLEEP GUARDIAN upon the unit is to promote protective sleep between the hours of 2300 hours to 0700 hours. A sleep guardian can be any band of nurse, health care assistant, doctor or consultant. Those who are allocated the role of sleep guardian ensure throughout the night that alarms, lights and staff voices are lowered. We are advocating that as a team where possible, any invasive nursing or medical interventions are performed before lights go out at 2300 hrs and from then on interventions are clustered to allow at least 1.5 – 2 hour periods of sleep. For those patients with a Richmond Agitation Score (RASS) of >1 eye masks and earplugs should be offered. We have worked with staff to reduce phone alarms, ventilation and bedside monitor alarms at the start of each night shift to reduce noise disturbance overnight within the bay. We have also worked with our procurement team to ensure all bins within the bays are soft-close. Furthermore, we have worked with the IT department to devise a monitor screensaver which reminds everyone to be a SLEEP GUARDIAN between the hours of 2300 –0700 hrs.

With patient safety always at the forefront of any initiative we have reinforced the ‘buddy’ system upon the unit. This ensures that every patient has a nominated nurse monitoring them even when their named nurse has stepped away from the bed space. Therefore, whilst alarms and lights are reduced, patient safety is still optimised.

Family / Friends

Visiting a relative or friend in Critical Care is a daunting and frightening experience for anyone. Once the patient begins to wake up and then displays behaviours associated with delirium relatives and friends feel at a loss of how to react and often express, ‘this is not the usual way they behave, speak or react.’ In order to help relatives and friends understand how delirium can affect patients, we have prepared a ‘DREAMS NOT DELIRIUM’ bedside information folder devised from guidelines set out in the LSCCCN Dreams Delirium Bundle.

Our information folder contains a ‘SLEEP MENU’ which asks relatives to specify how the patient would normally sleep, in terms of pattern, hours and sleep aids used. It also asks for information on what activities the patient would normally do during the day. This information then gives us the opportunity to get to know our patients’ likes and dislikes whilst they may still be sedated and intubated. Once a patient begins to wake we can have the necessary aids ready, such as glasses or hearing aids to help the patient to become orientated to the Critical Care environment. Also included within the folder there is a snapshot of why we assess for delirium taken from the National Institute of Clinical Excellence Guidelines for Delirium (Delirium prevention, diagnosis, and management CG103). In addition, there is information for relatives on what delirium is, how patients become delirious and what they can do to help. A communication sheet enables patients who are intubated or have a tracheostomy to point to or spell out phrases to indicate anything they wish nurses or family members to know. Conversely, there is advice for relatives of how to speak to patients, in soft tones and to re-orientate the patient to place, date and time. To further assist with orientation we have devised orientation boards for each bed space which display where the patient is, the day, date and their named nurse. There is also a section on here for relatives and friends to display photographs and cards so that when a patient does wake they feel safer in an alien environment, knowing their loved ones are visiting by seeing the cards and pictures placed by their bed space.

References:

Inouye, S., Foreman, M. D., Mion, L. C., Katz, K. H., Cooney, L. M. (2001) Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Archives of Internal Medicine. Vol. 161. Pp 2467-73.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellance (NICE) (2010) Delirium: Diagnosis, prevention and management. (CG 103) Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103/evidence/cg103-delirium-full-guideline3.

Page, V. (2008) Sedation and delirium assessment in the ICU. Care of the critically ill. Vol. 24. Pp. 153-8.