Intensivists need to prepare for compulsory reporting of public data, says Andrew Rhodes, London. It’s happened in surgery (see UK example), and it’s coming to intensive care, in the UK and the Netherlands. Rhodes was speaking at the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine annual congress in Berlin, 3-7 October.

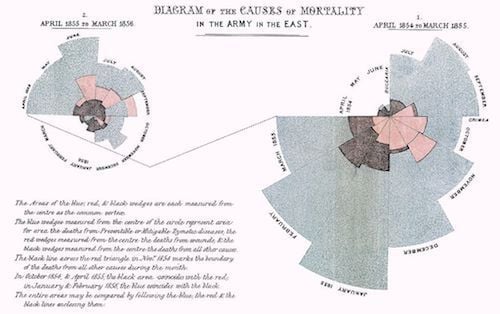

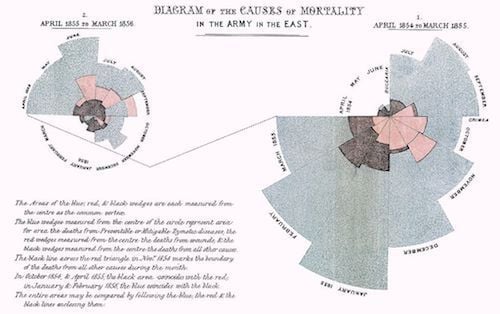

Florence Nightingale had it right, said Rhodes, in her notes on nursing, that nurses need to observe the sick (monitoring) and never let the patient be waked out of sleep. She also wrote: “To understand God’s thoughts, one must study statistics, for these are the measure of his purpose.” This aspect of her work, statistics, is perhaps not so well known, observed Rhodes. And he showed Nightingale’s rose diagram, causes of mortality in the army in the east.

Licensed under Public Domain via Commons

Critics have raised concerns about mortality rates by hospitals. There are suspicions about data quality, concerns about providers avoiding high risk cases, the need to hold windows of observation constant, the requirement for severity or risk adjustment, and, not least, reservations about the public’s ability to understand the data, said Rhodes. However, we can understand quality and measure it (Brook et al. 2000).

Sometimes you just have to work through the five stages of data grief:

Public reporting may lead to changes in healthcare delivery structures or processes, such as changing policy, adding services and increasing focus on clinical care. It may lead to behaviour change by patients or purchaser organisations. There is moderate evidence to show that there is no or minimal impact of public reporting on selection as measured by market share or volume.

There are issues around outcome choice and timeliness of reports, about mortality (30-day or in-hospital), and how to count mortality if a patient is discharged to another hospital. Should we aim for perfection or timely reports?

We need to understand what performance measures we will measure ICUs on. We need to choose which performance indicators to release to the public - likely a balance of process and outcome indicators. We need to give thought to the level of risk adjustment of outcome indicators and to the risks and benefits of disclosure. Disclosure should involve all relevant interest groups and education of the public and the media. Finally, it should be integrated with quality improvement strategies.

Rhodes showed a dashboard from his own institution. From this, for example, you can find out how long it takes for a patient to be discharged, amongst other metrics available.

Whether we like it or not there is now a requirement that we practise in an open and transparent fashion, concluded Rhodes. This includes the reporting of performance metrics. This will drive change, and we need to engage with it to ensure the change is in the best interest of our patients.

Claire Pillar

Managing editor, ICU Management

Image source: Top image - Pixabay; Middle image - Wikimedia Commons

Florence Nightingale had it right, said Rhodes, in her notes on nursing, that nurses need to observe the sick (monitoring) and never let the patient be waked out of sleep. She also wrote: “To understand God’s thoughts, one must study statistics, for these are the measure of his purpose.” This aspect of her work, statistics, is perhaps not so well known, observed Rhodes. And he showed Nightingale’s rose diagram, causes of mortality in the army in the east.

Licensed under Public Domain via Commons

Critics have raised concerns about mortality rates by hospitals. There are suspicions about data quality, concerns about providers avoiding high risk cases, the need to hold windows of observation constant, the requirement for severity or risk adjustment, and, not least, reservations about the public’s ability to understand the data, said Rhodes. However, we can understand quality and measure it (Brook et al. 2000).

Sometimes you just have to work through the five stages of data grief:

- Denial: data is wrong

- Anger: doesn’t apply to me

- Bargaining: I will get the correct data

- Depression: There’s nothing I can do about it

- Resolution: Acceptance and action

Benefits

There are possible benefits of routine disclosure of performance data, said Rhodes. Disclosure should lead to increased openness and transparency, it should lead to improved accountability and confidence, and this should drive up quality of care. The possible impacts are improved outcomes, but perhaps the intended impact could be allocative and technical efficiency. In cardiac surgery in the UK, there has been much debate about quality and performance reported at the individual consultant level. Other countries have started registries for surgical outcomes, which has led to changes in health policy.Key Questions

Does public reporting of results lead to improvements in the quality of healthcare? Certainly in the UK, mandatory reporting of C. diff rates led to improvement, observed Rhodes. There may be reduction in mortality - there is moderate strength of evidence for this. There are possible harms from public reporting, however, with varying levels of evidence. There may be increased mortality, but there is insufficient evidence for this. There is also insufficient evidence of inappropriate diagnosis or treatment. Risk aversion may result from public reporting, such as access restrictions and unintended provider behaviours, with moderate strength of evidence. For example, if you have to report on bacteraemia rates, you may think carefully about sending blood off for testing.Public reporting may lead to changes in healthcare delivery structures or processes, such as changing policy, adding services and increasing focus on clinical care. It may lead to behaviour change by patients or purchaser organisations. There is moderate evidence to show that there is no or minimal impact of public reporting on selection as measured by market share or volume.

Mortality After Surgery in Europe: EuSOS study

As one of the co-authors of the Lancet paper on mortality after surgery in Europe, a 7 day cohort study, Rhodes recalled some of the criticisms, such as differences in outcome measurements. In this study, it was not possible to validate source data,repeated analysis confirmed the findings, and the sensitivity analysis confirmed variability, but between different countries. Many of the criticisms were about the question the study was not designed to answer - the point estimate of mortality for individual countries. However, many countries have since started their own outcome analysis.Challenges

It is essential to ensure that data quality is good, emphasised Rhodes. Validation is effective, but resource intensive. It is possible to compromise on validation, as it is impossible to validate all data.There are issues around outcome choice and timeliness of reports, about mortality (30-day or in-hospital), and how to count mortality if a patient is discharged to another hospital. Should we aim for perfection or timely reports?

We need to understand what performance measures we will measure ICUs on. We need to choose which performance indicators to release to the public - likely a balance of process and outcome indicators. We need to give thought to the level of risk adjustment of outcome indicators and to the risks and benefits of disclosure. Disclosure should involve all relevant interest groups and education of the public and the media. Finally, it should be integrated with quality improvement strategies.

Rhodes showed a dashboard from his own institution. From this, for example, you can find out how long it takes for a patient to be discharged, amongst other metrics available.

Whether we like it or not there is now a requirement that we practise in an open and transparent fashion, concluded Rhodes. This includes the reporting of performance metrics. This will drive change, and we need to engage with it to ensure the change is in the best interest of our patients.

Claire Pillar

Managing editor, ICU Management

Image source: Top image - Pixabay; Middle image - Wikimedia Commons

Latest Articles

Performance, ICUs, Public dislosure, ESICM 2015

Challenges, benefits and way forward to public disclosure of intensive care performance data. Presentation by Andrew Rhodes at the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) congress 2015, Berlin.