ICU Management & Practice, Volume 20 - Issue 4, 2020

Illustrating PICS

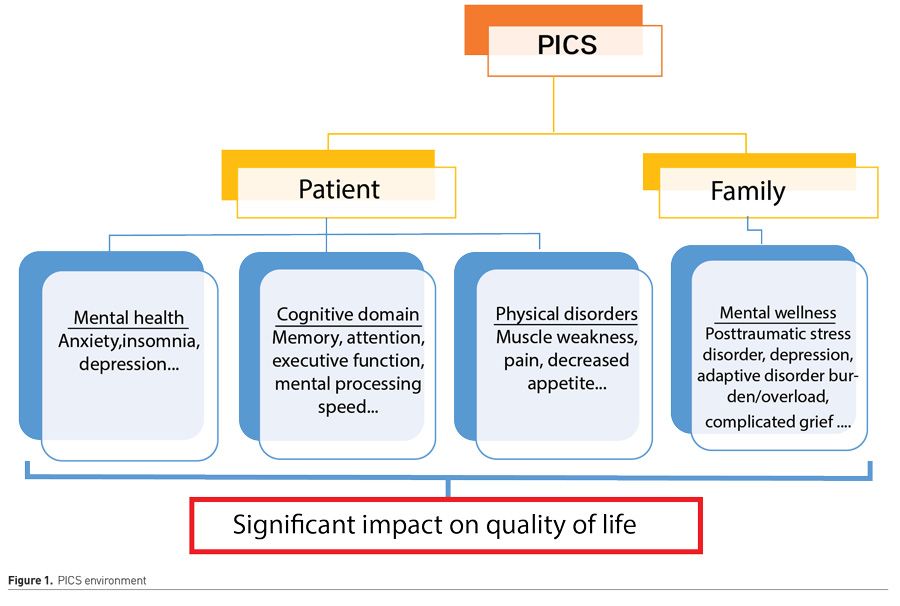

People who have been admitted to an Intensive Care Unit report a reduced quality of life for up to twelve years following critical illness compared to the general population (Flaatten and Kvåle 2001). This may not be surprising for most of the readers of this journal. First and foremost, during the first year following critical illness, patients state this lower quality of life, particularly within the physical domain (experiencing impairments in body function, basic and instrumental activities of daily living and participation) (Ohtake et al. 2018). These referred symptoms are part of a broader set, which together make up the post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), named after two expert meetings that took place in 2010 and 2012, including the Society of Critical Care Medicine and international specialists from non-critical care organisations. PICS was then defined as “as new or worsening impairment in physical, cognitive, or mental health status arising and persisting after hospitalisation for critical illness” (Needham et al. 2012; Harvey and Davidson 2016).

PICS is described in 30-50% of patients after ICU admission; differences are due to patient population included in the studies, patient comorbidities, measurement tools, and time frames. At the time of hospital discharge, between 46% and 80% of survivors experience cognitive impairment; 3 and 12 months after discharge, 40% and 34%, respectively. At 12 months, clinically significant symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress are present in 20% to 30% of survivors. Patients also refer other health problems: sleep disturbances (55%), ongoing pain (52%), airway irritation (45%), gastrointestinal rhythm disturbances (40%), dyspnoea (23%), dysphagia (19%), and nightmares about their time in ICU (14%) (Rai et al. 2019). Moreover, Marra et al. (2018) demonstrated in a multicentre cohort study that one or more post-intensive care syndrome problems were present in the majority of survivors. Still, concurring difficulties were coeval in only one out of four, being able to describe the possible existence of PICS subtypes, yet to be clearly defined.

Conversely, PICS can occur in both surviving and deceased patients' families (named PICS-Family or PICS-F). The long-term consequences on families are psychological, physical, and social. Approximately 10-75% of families suffer from anxiety; around 35% of families have depression and 8-42% symptoms accordant to post-traumatic stress disorder, which can persist for years (Schmidt and Azoulay 2012) (Figure 1).

Managing PICS effectively requires a clearer understanding of the associated risk factors. Lee et al. (2019) performed a systematic review of the risk factors for PICS and determined their effect size. Sixty risk factors were identified: those ICU related (uncontrolled pain or inappropriate sedation, presence and duration of delirium, immobility, steroids, prolonged mechanical ventilation, prolonged length of stay…) and those associated intrinsically to the patient (such as personal traits, own previous experiences, pre-existing anxiety, sepsis or ARDS on admission …). Significant risk factors for PICS included older age (OR 2.19), female sex (OR 3.37 for mental health), previous mental health problems (OR 9.45), disease severity (OR 2.54), negative ICU experience (OR 2.59), and delirium (OR 2.85). On the other side, major risk factors for PICS-F are poor communication between staff, lower educational level, and having a loved one who died or was close to death.

Decreasing PICS Incidence: Is it Possible?

Prevention strategies

To avoid the development of PICS, we must, as health professionals dedicated to the care of the critical patient, focus first on prevention measures:

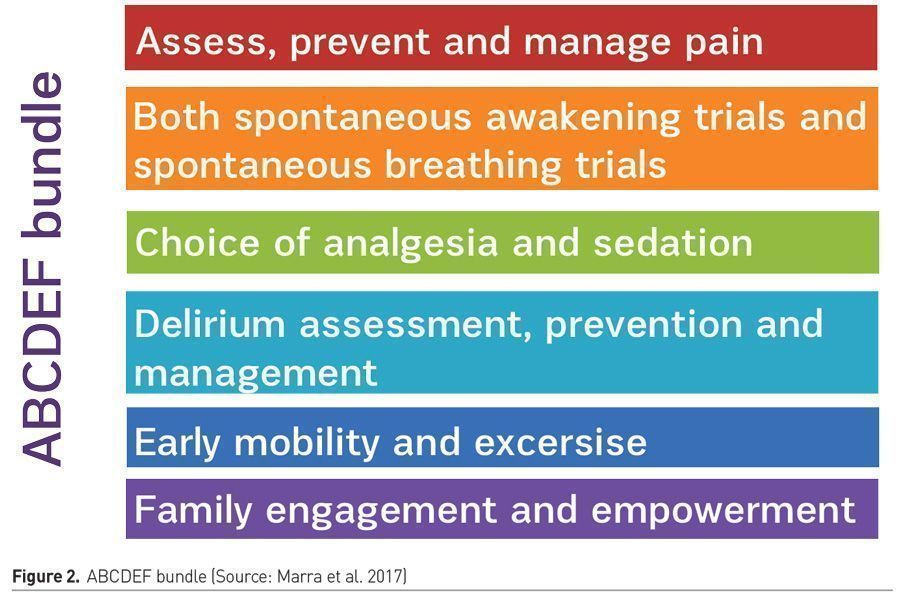

- Following the updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU PAD guidelines; Devil et al. 2018), adapted into the world-wide known ABCDEF bundle (Marra et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2020) (Figure 2).

- Early mobility programmes by integrating physical therapists and occupational therapists into the ICU setting (Fuke et al. 2018).

- Early psychological interventions by integrating psychologists in the critical care team, offering both patients and families, support, counselling, and education on stress management (Peris et al. 2011; Czerwonka et al. 2015).

- Use of ICU diaries: an illness narrative for patients written by nurses and patient’s relatives, allowing patients to reconstruct the story of their critical illness, helping them understand the seriousness of the process, and filling in gaps of memory. Its maintenance has inconsistently shown (depending on the methodological differences between trials) decrease in symptoms of PTSD and could be used as a tool to provide support and care to the patient and family (Garrouste-Orgeas et al. 2019; Kredentser et al. 2018; Garrouste-Orgeas et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2010).

- Keeping favourable nutritional status and sleep quality.

- Modifying the ICU environment, using patient care space as a treatment tool (Luetz et al. 2019).

Management strategies

However, once the patient presents symptoms consistent with PICS, we must first make an early diagnosis, and then try to manage the symptoms with the tools we currently have available. One significant barrier in the assessment of PICS is the lack of a single, validated clinical tool to assess impairments in all three domains of PICS rapidly. Wang et al. (2019) managed to validate the Healthy Aging Brain Care Monitor Self Report version (HABC-M SR) psychological and functional subscales as reliable tools to measure the severity of symptoms of PICS. Besides, Jeong and Kang (2019) aimed to develop a PICS questionnaire consisting of 18 items covering all three domains, demonstrating excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93). Future studies in search for a quick clinical tool to rapidly assess PICS are still needed.

Regarding management of PICS, developed different strategies are:

• Post-ICU rehabilitation programmes, including patient-directed exercises, in-home therapist sessions and telehealth delivery of therapy, bundled with cognitive rehabilitation (Denehy and Elliott 2012; Jackson et al. 2012).

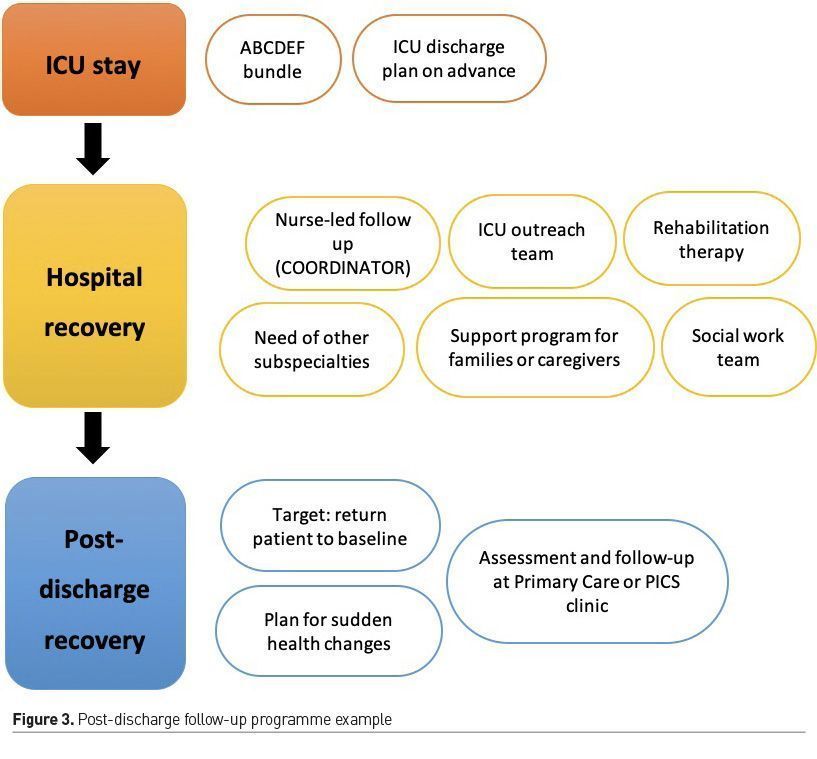

• Post-discharge follow-up programmes (Busico et al. 2019; Van Der Schaaf et al. 2015; Mehlhorn et al. 2014). A possible example can be seen in Figure 3 and outlined below:

Management of acute illness within the ICU

Following ABCDEF bundle and patient’s ICU discharge plan made on advance through the Continuity-of-Care Nursing team (search of patient's needs, assure a satisfactory hand-off with hospital ward team and discuss next steps with the patient and family).

Hospital recovery

- Follow-up programme by the ICU outreach team (span time and objectives agreed in advance).

- Nurse-led follow-up in the hospital ward (coordination with healthcare professionals and resource planning).

- Ward-discharge plan with the corresponding level of health care, guaranteeing the continuity of care.

- Optimal rehabilitation therapy: exercise, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-language pathology, or cognitive rehabilitation.

- Need of other subspecialties: Cardiology, Pneumology, Psychiatry, Otolaryngology

- Support programme for families/caregivers, aimed at reducing stress and anxiety, supporting fluid communication about the patient's condition and prognosis. Priority to the patient’s values and wishes in the shared decision-making process.

- Social work: assess the need for social support upon discharge (institutionalisation, Day Centre, home help...) and will inform and facilitate the necessary procedures to obtain economic and social support if needed.

Post-discharge recovery

- Targets: return the patient to baseline by promoting continuous care, sharing knowledge, professional experience, and availability of resources among professionals at all levels of care.

- Comprehensive assessment of the patient at the Primary Care Provider or PICS “clinic”: screening deficits in following areas: motor and sensory functions, communication problems, swallowing problems, post-traumatic stress symptoms, symptoms of anxiety and depression, cognitive functions, psychosocial and sexual adaptation.

- Assessment to be carried out at intervals defined by each of care programme (at discharge, at one month, at three months, at six months, at 12 months...).

- The programme must also include a plan for unforeseen health changes and what advice should be given to patients and caregivers in these cases.

Although it is widely accepted that follow-up activity at discharge is an effective intervention, research on such programmes has been disappointing. High quality randomised controlled trials with well-intentioned interventions designed and delivered by ICU teams after ICU discharge have not produced the desired results, and clinical evidence published to date is neither homogenous nor standardised (Schofield-Robinson et al. 2018; Walsh et al. 2015; Cuthbertson et al. 2009). There are several reasons why these interventions may have been ineffective. Among them: the complexity of the pathophysiology, the inability to identify and target high-risk groups, the impossibility of individualising therapy, and, in some cases, the lack of input from other expert providers such as physical therapists, neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, and rehabilitation physicians. According to the data provided, it is unlikely that follow-up interventions will be useful in the future if we do not achieve greater collaboration between the different parts of the health system.

• ICU survivor peer support groups provide an adequate space for survivors to share experiences, feelings, empathy, advice… with others, collaborating and helping each other through problems. They allow mental reframing, effective role-modelling, information sharing, and practical advice that is not readily available to healthcare professionals. These have also proved favourable in other situations (mental health disorders, substance abuse issues, or cancer survivors) and can lead to empowerment, self-advocacy, and improved overall outcomes (Mikkelsen et al. 2016; Haines et al. 2019).

What about PICS-F?

Most critical patients cannot express their wishes, ask questions, or assert their rights. In these settings, family members (or primary caregivers) take the lead: they start making decisions, sometimes decisive ones, continually trying to think about what the patient would have wanted at any given time. It is clear that, in this situation of uncertainty and fear, there is a risk of psychological distress. Therefore, symptoms such as anxiety, depression, or acute stress disorder may appear. Withal, it is only the beginning, since once the patient is discharged, he/she requires caregiving until recovery and return to baseline. Who would not burden in this situation? (Davidson et al. 2012; Torres et al. 2017; Petrinec and Martin 2018).

Moreover, caregiver problems may start early during ICU admission. They may require the greatest support at that time, even though issues such as posttraumatic stress disorder may not appear until a few months after discharge.

Possible interventions to decrease the psychological burden and improve family members’ experience could be (Schmidt and Azoulay 2012; Haines et al. 2018):

- Communication strategies: literature regarding family involvement in medical decision-making is growing, and extent data suggest that different methods of communication and inclusion in decision-making may play a vital role in outcomes.

- Access to information (brochures, adapted explanatory documents for laypersons…).

- Family participation in care: open visiting hours, regular meetings with nurses, and ICU staff…

- Psychological screening and support: need of psychologists during difficult times, developing coping strategies [problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, building resilience (Sottile et al. 2016)].

- Follow-up programmes for families: family debriefing visits, “family clinics,” increasing awareness of possible long-term consequences of intensive care among ICU survivors.

- Engaging intensive care survivors and caregivers to co-design recovery programmes.

- Peer support and development of social support networks.

As previously said with PICS, PICS-F is also a complex problem, and will probably require global, proactive, and multimodal interventions.

Conclusion

PICS is a growing public health issue. We must empower healthcare professionals from a range of different disciplines who give care to ICU survivors with information, education, and resources.

In the following months, considering the COVID-19 pandemic, the teams dedicated to this issue will face the conundrum of the increase in PICS/PICS-F cases. Patients who suffered the viral infection in its most severe form will present significant deterioration.

Improving the psychological outcomes of critically-ill patients and their families is challenging, as it depends on previous mental health, social and economic background, and cultural and geographic factors. Future research requires a precise framework to risk-stratify patients and family members, a consensus regarding what are the best tools to measure outcomes, and standardised follow-up approaches. We must emphasise the prevention of cognitive, physical, and psychological sequelae. We must meet the current gap in health services. Patients and their families need to know they are not alone.

Conflict of Interest

F. Gordo has performed consultancy work and formation for Medtronic. The other authors have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

PICS – post-intensive care syndrome

PICS-F - post-intensive care syndrome family

ICU – intensive care unit

OR – odds ratio

PAD – Pain, Agitation and Delirium

PTSD – posttraumatic stress disorder

References:

Busico M, das Neves A, Carini F, Pedace M et al. (2019) Follow-up program after intensive care unit discharge. Med Intensiva, 43(4):243-254.

Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK et al. (2009) The PRaCTICaL study of nurse-led, intensive care follow-up programs for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMJ, 339:b3723,

Czerwonka AI, Herridge MS, Chan L et al. (2015) Changing support needs of survivors of complex critical illness and their family caregivers across the care continuum: A qualitative pilot study of towards RECOVER. J Crit Care, 30:242–249

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ (2012)Family response to critical illness: post-intensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med, 40(2):618-24.

Denehy L, Elliott D. Strategies for post ICU rehabilitation (2012) Curr Opin Crit Care, 18: 503–508.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, et al.(2018) Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med, 46: e825–e873.

Flaatten H, Kvåle R (2001) Survival and quality of life 12 years after ICU: a comparison with the general Norwegian population. Intensive Care Med, 27:1005–1011.

Fuke R, Hifumi T, Kondo Y et al. (2018)Early rehabilitation to prevent post-intensive care syndrome in patients with critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 5;8(5):e019998.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Flahault C, Vinatier I et al. (2019) Effect of an ICU diary on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA;322(3):229-239

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Périer A, Mouricou P et al. (2014) Writing In and Reading ICU Diaries: Qualitative Study of Families’ Experience in the ICU. Harris F, ed. PLoS ONE;9:e110146.

Haines KJ, McPeake J, Hibbert Eet al. (2019) Enablers and Barriers to Implementing ICU Follow-Up Clinics and Peer Support Groups Following Critical Illness: The Thrive Collaboratives. Crit Care Med, 47(9):1194-1200.

Haines KJ, Quasim T, McPeake J (2018)Family and Support Networks Following Critical Illness. Crit Care Clin, 34(4):609-623.

Harvey MA, Davidson JE (2016) Post-intensive Care Syndrome: Right Care, Right Now…and Later. Crit Care Med, 44(2):381-5.

Jackson JC, Ely EW, Morey MC et al. (2012) Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the RETURN randomized controlled pilot investigation. Crit Care Med, 40: 1088–1097.

Jeong YJ, Kang J (2019)Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure post-intensive care syndrome. Intensive Crit Care Nurs, 55:102756

Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M et al.(2010) Intensive care diaries reduce new-onset posttraumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care;14:R168.

Kredentser MS, Blouw M, Marten N et al. (2018) Preventing posttraumatic stress in ICU survivors: a single-center pilot randomized controlled trial of ICU diaries and psychoeducation. Crit Care Med;46(12):1914-1922

Lee M, Kang J, Jeong YJ (2019)Risk factors for post-intensive care syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Crit Care. pii: S1036-7314(19)30178-X. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.10.004. [Epub ahead of print)

Lee Y, Kim K, Lim Cet al. (2020) Effects of the ABCDE bundle on the prevention of post-intensive care syndrome: A retrospective study. J Adv Nurs, 76(2):588-599.

Luetz A, Grunow JJ, Mörgeli Ret al.(2019) Innovative ICU Solutions to Prevent and Reduce Delirium and Post-Intensive Care Unit Syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 40(5):673-686.

Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, et al. (2017) The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit Care Clin, 33: 225–243.

Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Girard TDet al.(2018) Co-Occurrence of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome Problems Among 406 Survivors of Critical Illness. Crit Care Med, 46(9):1393-1401.

Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K et al. (2014) Rehabilitation interventions for post-intensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med, 42: 1263–1271.

Mikkelsen ME, Jackson JC, Hopkins ROet al. (2016) Peer Support as a Novel Strategy to Mitigate Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. AACN Adv Crit Care, 27(2):221-9.

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H et al. (2012) Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from the intensive care unit: a report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit. Care Med, 40:502–9.

Ohtake PJ, Lee AC, Scott JC et al. (2018)Physical Impairments Associated with Post-Intensive Care Syndrome: Systematic Review Based on the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Framework. Phys Ther, 98(8):631-645

Peris A, Bonizzoli M, Iozzelli D et al. (2011) Early intra-intensive care unit psychological intervention promotes recovery from posttraumatic stress disorders, anxiety, and depression symptoms in critically ill patients. Crit Care, 15:R41

Petrinec AB, Martin BR (2018)Post-intensive care syndrome symptoms and health-related quality of life in family decision-makers of critically ill patients. Palliat Support Care, 16(6):719-724

Rai S, Anthony L, Needham DM et al. (2019) Barriers to rehabilitation after critical illness: a survey of multidisciplinary healthcare professionals caring for ICU survivors in an acute care hospital. Aust Crit Care. pii: S1036-7314(18)30354-0. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.05.006 (Epub Ahead of Print)

Schmidt M, Azoulay E (2012) Having a loved one in the ICU: the forgotten family. Curr Opin Crit Care, 18(5):540-7.

Schmidt M, Azoulay E (2012) Having a loved one in the ICU: the forgotten family. Curr Opin Crit Care, 18(5):540-7.

Schofield-Robinson OJ, Lewis SR, Smith AF et al (2018)Follow-up services for improving long-term outcomes in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 11:CD012701.

Sottile PD, Lynch Y, Mealer M et al. (2016)Association Between Resilience and Family Member Psychologic Symptoms in Critical Illness. Crit Care Med, 44(8):e721-7

Torres J, Carvalho D, Molinos Eet al. (2017) The impact of the patient post-intensive care syndrome components upon caregiver burden. Med Intensiva, 41(8):454-460.

Van Der Schaaf M, Bakhshi-Raiez F, Van Der Steen Met al.l (2015) Recommendations for intensive care follow-up clinics; a report from a survey and conference of Dutch intensive care. Minerva Anestesiol, 81: 135–144.

Walsh TS, Salisbury LG, Merriweather JL al (2015) Increased hospital-based physical rehabilitation and information provision after intensive care unit discharge. TheRECOVER randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med, 175(6):901–910

Wang S, Allen D, Perkins A et al. (2019)Validation of a New Clinical Tool for Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. Am J Crit Care, 28(1):10-18.