ICU Management & Practice, Volume 16 - Issue 3, 2016

Use of point-of-care test devices in the emergency department has shown significant benefits in patient management. A proper governance policy will ensure credible, effective and safe practice.

Emergency Department (ED) practices have evolved, modified and developed pathways over the years to recognise and initiate appropriate early treatment for acutely unwell patients. One of the major contributing factors has been the use of point-of-care test (POCT) devices, which have the ability to provide drastic improvement in the turnaround time (TAT) of test results. Early goal-directed therapy in sepsis, early recognition of neutropenic sepsis, acute coronary syndrome, an unconscious patient with suspected drug use needing antidotes: the list is exhaustive where early test results have shown appropriate treatment has been initiated and has directly affected the outcome.

ED overcrowding is an international problem and waiting times have been increasing over time. France, Sweden, UK, New Zealand and Canada have all passed explicit length-of-stay time targets, requiring that patients leave the department within 4-8 hours. Overcrowding and prolonged wait times have been linked to adverse clinical outcomes and decreased patient

satisfaction. While no one factor can be identified as the root cause of this issue, decreased delays in sample collection and test results can provide healthcare professionals with the opportunity to arrive at faster care management decisions, resulting in increased patient throughput and decreased average wait times. ED performance is dependent on processes and capacity in other hospital departments as well as other parts of the health and care system (Kings Fund 2016; Larsson et al 2015).

In the United Kingdom, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) published a document in December 2013, which provides advice and guidance on the management and use of point-of-care testing (POCT) in in vitro diagnostic (IVD) devices (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency 2013). The MHRA guidance document is a very helpful text to use to establish such a service. In Europe POCT devices are regulated under the 1998 European Directive 98/79/EC on in vitro diagnostic medical devices (Council Directive 1998).

Definition

POCT is defined as any analytical test performed for a patient in primary or secondary care (ED) settings by a healthcare professional outside the conventional laboratory setting. Other terms commonly used to describe POCT include:

• Near patient testing (NPT)

• Bedside testing

• Extra-laboratory testing

• Disseminated/decentralised laboratory testing

What is Out

There?

There has been a continual rise in the use of POCT due to the drive to improve patient pathways and as a result of technological advances. Developments in fluid handling, microchip and miniaturisation technology and improved manufacturing processes are producing POCT devices that are more robust and less prone to error than previous generations.

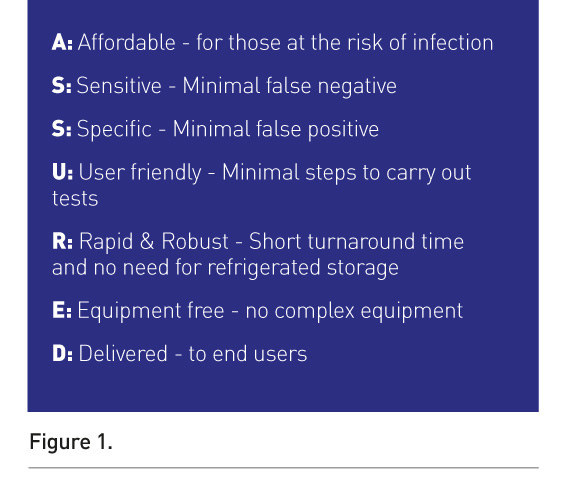

The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided ASSURED guidelines for those developing new POCT devices for detecting sexually transmitted infections (Figure 1).

This principle can be applied to develop any new POCT device (St John and Price 2014). POCT Systems can be categorised as:

• Non-instrumental systems: disposable systems or devices. These vary from reagent test strips for a single analyte to sophisticated multi-analyte reagent strips incorporating procedural controls, e.g. urine dipsticks, urinary pregnancy tests and urine toxicology screens.

• Small analysers, usually hand- or palm-held devices, which can vary in size, e.g. blood glucose meters, blood ketone meters.

• Desktop analysers are larger and include systems designed for use in clinics or small laboratories, e.g point-of-care haematology analyser for full blood count, portable blood analyser for measuring urea, creatinine, and blood gas analysers.

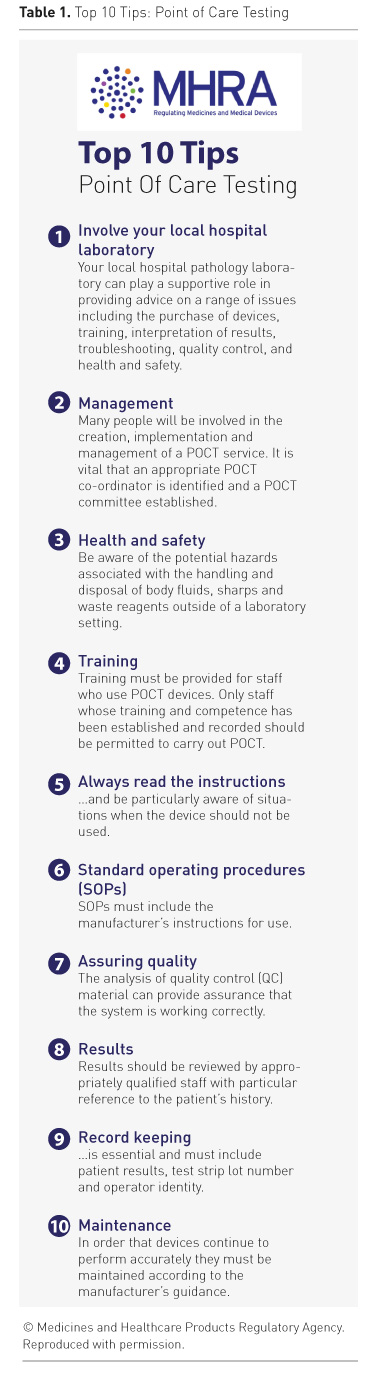

MHRA documentation provides

guidance on how to implement POCT in a secondary setting like the ED (Table

1) (MHRA 2013).

See Also:How useful is multi-organ point-of-care ultrasound?

Prior to

Implementation of a POCT Service in the Hospital

1.Involvement of local hospital pathology laboratory

It is very important in a secondary setting like the ED to have a close liaison between users and local pathology labs as they can provide advice on a range of issues such as purchase, training, interpretation of results, troubleshooting, quality control, quality assessment and health and safety.

2. Identifying

the need for POCT

It is essential to establish a clinical need and consider the benefit of introducing POCT. The motivation could be to improve the patient pathway and experience, for example.

3. Advantages and disadvantages of POCT

The obvious advantages are improved TAT, better monitoring for conditions requiring frequent testing, improved patient experience. The disadvantages may be poor quality analysis, poor record keeping, lack of results interpretation, inappropriate testing.

4. Costs

It is important to include cost analysis and it should be taken into consideration whether the hospital or healthcare organisation is in a position to include variable professional costs apart from capital costs.

5. Choosing the right equipment

There should be discussion between the clinical

users, laboratory, manufacturers, and the estates

department prior to finalising the equipment.

6. Clinical governance

It is important to set up a point-of-care committee who can regulate use of POCT as an alternative to laboratory testing. Use of POCT is a clinical governance issue and subject to examination of clinical effectiveness.

Management and Organisation of POCT

1. Responsibility and accountability

A POCT coordinator needs to be appointed who has the authority and overall responsibility for the service at the beginning of the development process. A multidisciplinary POCT committee who can oversee the POCT activity in secondary settings should also be established.

2. Training

Staff who have completed the mandatory training and achieved competency should be permitted to carry out POCT.

3. Instructions for use

Staff must be familiar with the manufacturer’s instructions for use and the instruction manual should be readily available.

4. Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

It is strongly recommended to have SOPs which are readily available alongside the manufacturer’s instructions.

5. Health and safety

Staff users must recognise the hazards of handling and disposing of body fluids and sharps outside a laboratory setting.

6. Infection

control

Staff users should be reminded of the importance of universal infection control precautions.

7. Quality

assurance (QA)

This is an essential component of POCT and encompasses proper training and review of overall performance. The essential components of QA are internal quality control (IQC), external quality assessment (EQA), and parallel testing; they can help ensure reliable results if applied rigorously.

IQC methods primarily ensure that the results obtained are accurate and consistent. This can be achieved by analysis of a set of QC specimens provided by the manufacturer. This can reassure the user. A log of QC activity needs to be maintained and reviewed by the POCT committee on a regular basis.

EQA is performed by testing samples containing an undisclosed value received from an external source. EQA schemes may be operated by the manufacturer or by dedicated EQA providers.

Parallel testing of patient samples by the central laboratory can provide additional confirmation of device accuracy. This should be integrated in the EQA practice when laboratory results are available.

8. Maintenance

It is important to follow the manufacturer’s guidance on maintenance for safe and effective use of POCT devices.

9. Accreditation

This is an assessment by an external body of the competence to provide a service to a recognised standard. Independent confirmation helps provide reassurance to the users of this service.

10. Record keeping

It is important to keep accurate records of patient results from POCT devices.

11. Information technology

Support from IT systems to manage data, workstations and laboratory information is crucial for successful use of POCT devices.

12. Adverse incident reporting

The MHRA has two parallel reporting systems for device-related incidents, one for manufacturers and the other for users.

Clinical Scenarios for Use of POCT in ED

Rooney and Schilling (2014) outline several examples where use of POCT has led to improved patient outcomes.

Acute coronary syndrome

Many patients present to the ED with symptoms that suggest acute coronary syndrome (ACS). A rapid rule-out protocol using a combination of high-sensitivity cardiac Troponin I testing, risk score and electrocardiogram has been shown to be safe and effective in identifying low-risk patients (Than M et al. 2012). A randomised controlled trial that evaluated the performance of POCT for cardiac biomarkers on patients with suspected myocardial infarction showed a 20% greater discharge rate during the initial evaluation process when POCT was performed (Goodacre et al. 2011). The follow-up study that evaluated the financial implications of POCT found variable results (Bradburn et al. 2012).

Venous thromboembolic disease

Patients who have low risk but are suspected to have a venous thromboembolic disease have a D-Dimer test to rule out the disease. Use of POCT testing has shown a reduction in ED stay by 60 minutes and a 14% reduction in admissions (Lee-Lewandrowski et al. 2009).

Severe sepsis

Elevated blood lactate levels have been shown to be a sensitive marker of impaired tissue perfusion and of anaerobic metabolism in patients with suspected sepsis. This is a valid identification method for patients who will benefit from early aggressive goal-directed therapy.

Stroke

Early thrombolysis in patients presenting with ischaemic stroke has shown significant benefits. It is very important to institute this treatment as soon as possible. Apart from performing an immediate CT scan it is important to know the coagulation status, as there is an increased risk of bleeding if they are deranged, which can cause a potentially serious outcome. A POCT coagulation test not only avoids unnecessary delay of a time-critical intervention like thrombolysis, but also ensures that the patient is safe to receive it.

Recognising substance abuse in an unconscious patient, metabolic emergencies, ectopic pregnancy—the list goes on of where POCT tests have shown benefits by reducing the diagnosis time and enabling initiation of treatment at the earliest time.

Conclusion

The number of tests that can be performed outside a conventional laboratory, especially in the ED, has grown significantly over the past two decades. This is primarily driven by the idea that the care provided is brought closer to the patient. There is substantial evidence of where use of POCT devices has shown benefits in recognising the ill patient, helped establish immediate treatment thereby reducing the waiting for diagnosis and also improved the patient journey time from ED to acute medical wards. All this will eventually accumulate into a good patient experience. Patient satisfaction can help gather political support to invest in development and implementation of this technology. However, it is of utmost importance that any department or hospital that plans to invest in a POCT device has a strict governance policy.

Conflict of interest

Shashank Patil declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ED emergency department

POCT point of care testing

MHRA Medicines and Healthcare products

Regulatory Agency

POCT point-of-care test

QA quality assurance

QC quality control

TAT turnaround time

References:

Council Directive (EC) 1998/79/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 1998 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices. [Accessed: 26 August 2016] Available from eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31998L0079

King’s Fund (2016) What's going on in A&E? The key questions answered. [Accessed: 26 August 2016] Available from kingsfund.org.uk/projects/urgent-emergency-care/urgent-and-emergency-care-mythbusters

Larsson A, Greig-Pylypczuk R, Huisman A (2015) The state of point-of-care testing: a European perspective. Ups J Med Sci, 120(1): 1–10.

PubMed ↗

Medicines and Healthcare Products regulatory Agency (2013) Management and use of IVD point of care test devices. MHRA V1.1. [Accessed: 26 August 2016] Available from gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/371800/In_vitro_diagnostic_point-of-care_test_devices.pdf

St John A, Price CP (2014) Existing and emerging technologies for point-of-care testing. Clin Biochem Rev 35 (3) 2014 155-167.

PubMed ↗

Rooney KD, Schilling U. (2014) Point-of-care testing in the overcrowded emergency department-can it make a difference? Crit Care. 2014; 18(6): 692.

Than M, Cullen L, Aldous S (2012) 2-hour accelerated diagnostic protocol to assess patients with chest pain symptoms using contemporary troponins as the only biomarker: the ADAPT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol, 59(23): 2091-8.

PubMed ↗

Goodacre S, Bradburn M, Fitzgerald P et al. (2011) The RATPAC (Randomised Assessment of Treatment using Panel Assay of Cardiac markers) trial: a randomised controlled trial of point-of-care cardiac markers in the emergency department. Health Technol Assess, 15(23): iii-xi, 1-102.

PubMed ↗

Bradburn M, Goodacre SW, Fitzgerald P et al. (2012) Interhospital variation in the RATPAC trial (Randomised Assessment of Treatment using Panel Assay of Cardiac markers). Emerg Med J, 29(3): 233-8.

PubMed ↗

Lee-Lewandrowski E, Nichols J, Van Cott E et al. (2009) Implementation of a rapid whole blood D-dimer test in the emergency department of an urban academic medical center: impact on ED length of stay and ancillary test utilization. Am J Clin Pathol, 132(3): 326-31.

PubMed ↗