ICU Management & Practice, Volume 16 - Issue 1, 2016

Knowledge about current research evidence is required by clinicians in order to practise safe and effective care. The health librarian occupies a unique position between knowledge resources and knowledge consumers. As such, the librarian is perfectly poised to channel accurate, reliable knowledge into the hands of the healthcare team, who can then confidently apply evidencebased decisions.

Traditionally, the library has been the domain of the doctor studying for examinations or the nurse borrowing books for academic study. In the UK health libraries are becoming anything but traditional; they provide access to the best clinical evidence and offer high-quality information consultancy services that support the key functions of an evolving National Health Service (NHS) (Health Education England 2015). Librarians possess specialised skills in searching the available evidence and presenting it in a digestible format to busy clinicians and managers to help them make informed decisions about patient care, support guideline development, and bridge the gap between research and practice (Brettle et al. 2010). Librarians are casting off their ties to the library space and venturing out into clinical areas, taking knowledge and information to the frontline, where it is needed the most (Harrison 2009).

At Wirral University Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (WUTH), the critical care team employs the expertise of a librarian to ensure that decisions about patients are made utilising the best available knowledge. The initiative has been so effective that the team is embarking on a funded research study to explore the feasibility and value of the librarian as a ‘knowledge mobiliser’.

Background

The drive for evidence-based practice has been inherent in the NHS for many years, emerging from the principles of high-quality and patientcentred care sanctioned in the NHS Constitution (Department of Health 2012). Within the pressured environment of critical care, clinicians can experience several barriers to evidence-based practice, including information overload, shortage of time, lack of searching skills and limited access to information technology in a ward setting (Flynn 2010; Lappa 2005). Having easy access to the best evidence in the right place, at the right time, is an important first step in evidence-based practice (Pronovost et al. 2008).

Health librarians are trained and experienced in conducting high-quality evidence searches on behalf of clinicians (Harrison and Sargeant 2004). Studies show that librarians can influence clinician behaviour (Urquhart et al. 2007), and contribute to a range of patient and organisational outcomes including potential cost savings (Brettle et al. 2011). For librarian support to be most effective, it should be positioned in the right place in the decisionmaking process. At WUTH, the ward round was identified as the place where most discussions about patient care took place. Critical care ward rounds are central to team communication, the development of patient care plans and changes in practice (Dodek and Raboud 2003). A model was developed whereby the librarian attends ward rounds as part of the multidisciplinary team.

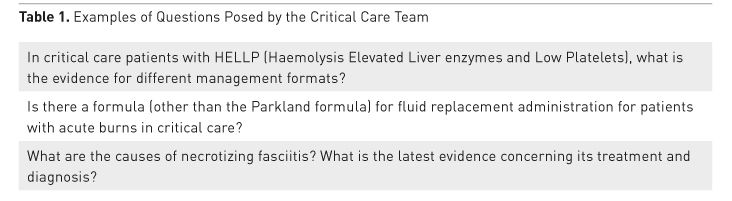

Over a ten-month trial period the librarian attended ward round once a week and collected questions posed about the patients’ condition or treatment by the team (Table 1). Having returned to the library the librarian undertook a search of relevant information resources. Due to time pressures, a speedy yet robust evidence search was required, so search strategies were informed by the hierarchy identified in the 5S model by Haynes et al. (2006). The 5S model encourages searchers to begin with the highest level of resource in the hierarchy, systems, before moving on to summaries, synopses, syntheses and finally, individual studies, until an acceptable answer to the question is found. Thus a range of resources were searched in order to compile a summary of any guidelines, studies or clinical recommendations relating to the question posed. The evidence summary was returned to the critical care team later that day.

Data from evaluation forms were collated and analysed at the end of the ten-month period. Respondents said that the evidence summary provided by the librarian gave them a better understanding of the treatment, improved patient management and aided treatment decisions, suggesting that the presence of the librarian makes a positive impact on clinical decision-making.

Evaluation data did also point to some areas for improvement. Questions on ward round were predominantly posed by medical staff, and it was felt that other staff groups should be encouraged to ask questions too. It was suggested that the speed of response from the librarian could be improved if a tablet or other mobile device was available for use at the bedside, rather than requiring a return trip to the library to access a computer. There was also a demand for library support in other areas of the department, for example, to support management decision-making, journal clubs and departmental meetings.

The evidence-supported ward round continued on a regular basis. Gradually the role of the librarian expanded beyond ward round, to support the departmental journal club and provide evidence to support decisions around purchasing equipment. We know through ongoing evaluation and feedback that library support has informed the development of clinical guidelines, the continuing professional development of staff and has contributed to service development.

Overall, the initiative has produced a number of positive benefits to the critical care team. The presence of the librarian enables access to knowledge and evidence at the point of need, saving time and effort. The regular visibility of the librarian prompts a questioning and learning culture within the team. Embedding library support within decision-making ensures that more clinical questions are pursued and researched by a trained information professional with experience in complex search methods. The librarian also performs an important function in compiling and summarising the relevant search results for easy absorption into patient discussions. In this context the librarian can usefully act as a valuable decision-making resource for the clinical team.

Some barriers perceived by the team included resource limitations and misconceptions about the role of a librarian. A persuasive case was made to purchase a tablet to enable quicker retrieval of information at the bedside. How the librarian might support decision making was explained prior to each ward round to encourage the team to utilise this resource. Even so, the librarian was frequently mistaken to be a pharmacist or other team member, as the concept of a librarian in a clinical area was so novel. Time and effort to explain the concept at a management level was also important to ensure that the organization embraced the initiative.

Research Study

In 2015 WUTH successfully bid for funding from Health Education North West (HENW) to develop a research study exploring the role of the librarian as ‘knowledge mobiliser’ in critical care, based on the several years of work undertaken previously. The study will go beyond the original concept of ward round support to examine a departmental-wide approach to supporting knowledge mobilisation, including the knowledge requirements of critical care patients and families.

Knowledge mobilisation (also referred to as knowledge translation, research utilisation, knowledge utilisation, research transfer, knowledge transfer and implementation science (McKibbon et al. 2012)) is a complex concept that describes the process of enabling research evidence to be applied in practice for beneficial outcomes. In healthcare, the term knowledge mobilisation is predominantly used to describe the activities that involve moving knowledge from its producers (academic researchers, research organisations) to its users (clinicians, managers, other decision-makers and patients/ families) to improve people's health.

Following consultation with critical care patients and their families, the study will also explore the role of the librarian in mobilizing accurate and evidence-based patient information. Patient and public engagement undertaken at WUTH found that critical care patients and families feel that they have specific information needs, and that improving information that they are given is a priority in terms of patient experience.

A librarian is perfectly placed to adopt the role of knowledge mobiliser within a team. This study aims to build on previous work to examine the contribution of the librarian to patient care. The study is due to finish towards the end of 2016.

Next Steps

Embedded library support in critical care carries several potential benefits for healthcare,including enhanced decision-making, education provision and well-informed patients and families.To realise these benefits requires persuasion at a management level and clear explanation at department level to ensure that the concept is embraced wholeheartedly. Adequate resources and systematic evaluation of the initiative are also required in order to ensure constancy and demonstrate value respectively.

The results of the study will signal the way forward in developing the role of librarian in critical care even further. The model that is developed could potentially be one that is transferable to other clinical areas that are required to make clinical decisions in a fastpaced environment.

References:

Brettle A, Maden-Jenkins M, Anderson L et al. (2010) Evaluating clinical librarian services: a systematic review. Health Info Libr J, 28(1): 3-22.

Department of Health (2012) The NHS constitution for England. [online]. [Accessed 26 Jan. 2016]

Dodek P, Raboud J (2003) Explicit approach to rounds in an ICU improves communication and satisfaction of providers. Intensive Care Med, 29(9): 1584-8.

Flynn M, McGuinness C (2010) Hospital clinicians’ information behaviour and attitudes towards the Clinical Informationist: an Irish survey. Health Info Libr J, 28(1): 23-32. DOI 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2010.00917.x

Harrison J, Beraquet V (2009) Clinical librarians, a new tribe in the UK: roles and responsibilities. Health Info Libr J, 27(2): 123-32.

Harrison J, Sargeant S (2004) Clinical librarianship in the UK: temporary trend or permanent profession? Part II: present challenges and future opportunities. Health Info Libr J, 21(4): 220-6.

Haynes RB (2006) Of studies, syntheses, synopses, summaries, and systems: the "5S" evolution of information services for evidence-based healthcare decisions. Evid Based Med, 11(6): 162-4.

Health Education England (2015) Knowledge for healthcare: a development framework. [Accessed 26 Jan. 2016]

Lappa E (2005) Undertaking an information-needs analysis of the emergency-care physician to inform the role of the clinical librarian: a Greek perspective. Health Info Libr J, 22(2): 124-32.

Marshall J, Sollenberger J, Easterby-Gannett S et al. (2013) The value of library and information services in patient care: results of a multisite study. J Med Libr Assoc, 101(1): 38-46.

McKibbon K, Lokker C, Wilczynski N et al. (2012) Search filters can find some but not all knowledge translation articles in MEDLINE: an analytic survey. J Clin Epidemiol, 65(6): 651-9.

Pronovost P, Berenholtz SM, Needham D (2008) Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ, 337: a1714.

Sudsawad P (2007) Knowledge translation: introduction to models, strategies, and measures. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research. [Accessed: 26 January 2016] Available from ktdrr.org/ktlibrary/articles_pubs/ktmodels

Urquhart C, Turner J, Durbin J et al. (2007) Changes in information behavior in clinical teams after introduction of a clinical librarian service. J Med Libr Assoc, 95(1): 14-22.