ICU Management & Practice, Volume 20 - Issue 4, 2020

Consequences and Recovery of Laryngeal Function

Introduction

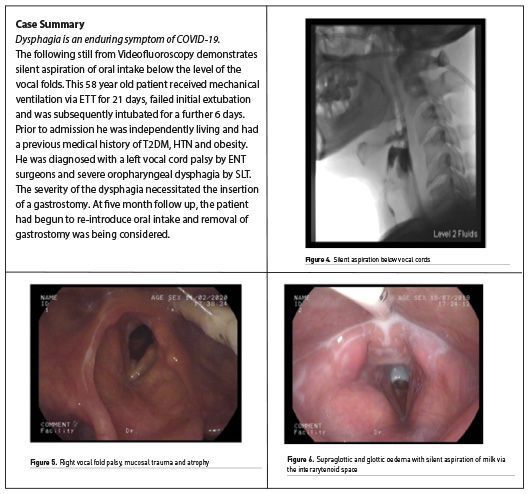

COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic in March 2020, with the virus SARS-CoV-2 causing severe acute respiratory syndrome (Williamson et al. 2020). Among patients hospitalised with COVID-19, up to one quarter required Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission (Huang et al. 2020). For those where COVID-19 led to severe respiratory disease secondary to hypoxaemic respiratory insufficiency or failure, invasive ventilation via endotracheal tube (ETT) was required (Meng et al. 2020). Laryngeal injury following ETT intubation has previously been widely cited as a transient or lasting complication impacting on voice and swallowing and functional outcome (Brodsky et al. 2018; Macht et al. 2011; Schefold et al. 2017; Wallace and McGrath 2020).

Recovery from laryngeal injury and related dysfunction must be managed by a highly skilled multidisciplinary team (Brodsky 2020). Further insult to a fragile respiratory system from laryngeal dysfunction can lead to serious consequences, including aspiration pneumonia, delayed tracheostomy weaning and lack of functional communication. An emerging, distinctive characteristic of the COVID-19 cohort is the duration of ventilator reliance, reported as high as 20 days (Stam et al. 2020). Prolonged intubation is paired with delayed insertion of tracheostomies, increasing the risk of laryngeal trauma. Furthermore, it is possible that the oropharyngeal symptoms of COVID-19, such as cough, loss of taste/smell and pain in the pharynx may have an additional impact on laryngeal function (Lovato et al. 2020; El-Anwar et al. 2020).

Laryngeal Injury and Dysfunction During Critical Illness

Intubation Phase

Endotracheal intubation in patients with COVID-19 is a high-risk procedure for staff, requiring full personal protective equipment (PPE) which may impact on the procedure (Cook et al. 2020). Furthermore, airway oedema in those with COVID-19 has been highlighted and anecdotal reports of difficult intubations have also been discussed (McGrath et al. 2020). In these circumstances, laryngeal injury such as mucosal trauma and damage to anatomical structures may be heightened.

The ETT sits in a vulnerable anatomical region for laryngeal function. As the ETT tube is inserted, it passes the arytenoid cartilages, cricoarytenoid joints and vocal folds which are all susceptible to trauma and residual laryngeal complications, manifesting as airway, voice and swallowing impairments (Mota et al. 2012). The recurrent laryngeal nerve innervating the laryngeal musculature is vulnerable to compression by the tube cuff especially if the cuff sits too high, or the cuff pressure exceeds capillary perfusion pressure (Miles et al. 2018). A recent study in over 200 patients intubated for more than 48 hours found that larger tube size was associated with an increased risk of aspiration and laryngeal granulation tissue (Krusciunas et al. 2020).

For those with COVID-19, additional risk factors contributing to laryngeal injury have not yet been investigated. Characteristics that may predispose patients with COVID-19 to neuropathy include age, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, corticosteroids, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and laryngopharyngeal reflux (Tadié et al. 2010; Williamson et al. 2020). Ponfick et al. (2015) found pathologic swallowing in 91% and hypoaesthesia of the larynx in 77% of patients with critical illness polyneuropathy. While the sedative management of COVID-19 patients during the intubation phase often precludes verbal communication, during the sedation hold phase some patients may attempt to vocalise while the ETT remains in situ, posing further risk of laryngeal trauma.

It is well known that prolonged intubation results in laryngeal complications but even transient intubation has been shown to cause mucosal trauma and laryngeal injury (Ng et al. 2019). Prolonged intubation is also known to correlate with post-extubation complications, including laryngeal stenosis, with a reported incidence of 5% in those intubated for 6-10 days (Bonvento et al. 2017). Piazza et.al. (2020) highlights the need for a high-level of suspicion for laryngotracheal stenosis development in COVID-19 patients following long-term intubation and tracheostomy. A description of stenosis in a COVID-19 patient is detailed in the case study below. Laryngeal oedema may negatively impact decision making regarding the safety of extubation, and increase the need for tracheostomy insertion (McGrath et al. 2020). In the COVID-19 RECOVERY trial, critically ill patients assigned to receive dexamethasone corticosteroid resulted in a lower 28-day mortality (Horby et al. 2020). Whilst the use of the dexamethasone may reduce oedema and airway complications, the reported side-effects such as hyperglycaemia, weakness and delirium may further impair communication, laryngeal and swallowing functions.

Prone ventilation has been used as an adjuvant therapy for treatment of acute respiratory distress in those with COVID-19, with some patients being proned repeatedly for up to 16 hours (Zang et al. 2020). Whilst adverse effects such as nerve palsies, pressure ulcers and oropharyngeal swelling are reported, the direct effect of proning on the larynx is not fully understood (Kwee et al. 2015). However, it may be hypothesised that the pressure exerted by the ETT on the laryngeal mucosa may exacerbate laryngeal dysfunction. Furthermore, prolonged bed rest, immobilisation and critical illness are key causes of muscle wasting and loss in ICU patients (Koukorikos et al. 2014; Parry and Puthucheary 2015). Up to 30% muscle mass loss is reported to occur within the first 10 days, however in patients undergoing prone ventilation this may be expedited (Kortebein et al. 2008). A combination of these factors may contribute to sarcopenia-related dysphagia, which has been demonstrated in elderly patients (Zhao et al. 2018). Generalised decline in muscle mass can coincide with weakening of the swallowing musculature and whilst the average age of ICU admissions is lower for COVID-19 patients, the potential impact of muscle wasting should remain a consideration and an age-related red flag.

Tracheostomy Phase

The timing of tracheostomy insertion in the critically ill COVID-19 patient has been a key area of discussion. For patients with COVID-19, tracheostomy insertion was deemed a high risk and an aerosol generating procedure (AGP) (ENT UK 2020). The balance between delaying insertion to reduce risks to staff during the patient’s most infective period and the extended duration of intubation has been discussed (McGrath et al. 2020). While prolonged ventilation is often necessitated in the COVID-19 cohort, clinicians should remain cognisant of the long term effects of prolonged intubation on laryngeal function. Following insertion, the presence of a tracheostomy tube and inflated cuff can impact upper airway sensitivity, respiratory/swallowing synchronisation and lead to disuse atrophy of laryngopharyngeal musculature (Garuti et al. 2014). Careful assessment of secretion management, cuff deflation tolerance and cough effectiveness by the multidisciplinary tracheostomy team should aim to determine risks to and optimise recovery of pulmonary function in the COVID-19 patient (Garuti et al. 2014). In-depth assessment by SLTs using Fibreoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) is the most accurate method for assessing oropharyngeal secretions, detecting and managing aspiration risks and for guiding multidisciplinary management and rehabilitation of laryngeal complications (Hafner et al. 2008; McGrath and Wallace 2014; Scheel et al. 2015).

While respiratory compromise associated with COVID-19 has been the most frequently reported, concomitant central and peripheral nervous system impairments have also been detailed (Paterson et al. 2020). Encephalopathy, encephalitis, ischaemic stroke and Guillain-Barré syndrome have all been observed in patients with COVID-19 (Paterson et al. 2020). The presence of central and peripheral nerve involvement further increases the risk of neurogenic laryngeal dysfunction (McIntyre et al. 2020; Schefold et al. 2017). Glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve neuropathies have been identified in a case study of a severely ill COVID-19 patient (Aoyagi et al. 2020). Cranial nerve impairments may exacerbate laryngeal dysfunction and these issues frequently delay recovery times.

Delirium and COVID-19

The inability to vocalise during critical illness can be a significant contributing factor to delirium, anxiety and psychological distress. A range of studies report this as one of the most frustrating and anxious experiences for mechanically ventilated patients (Ford and Martin-Harris 2016). Hospital policies restricting family visitations due to infection control precautions during the pandemic may further contribute to feelings of isolation and disorientation. When unable to vocalise patients have reported feeling trapped, caged, and a loss of personhood and control (Ford and Martin-Harris 2016).

Delirium occurs as a consequence of direct central nervous system invasion as a secondary effect of multiple organ system failure, sedation or environmental factors such as staff wearing PPE (Kotfis et al. 2020). Early restoration of voice can reduce anxiety levels in patients with tracheostomies (Liney et al. 2019). Early evaluation by the SLT and physiotherapist, to assess readiness for cuff deflation or a one way valve application facilitates greater patient participation in treatment. Input from clinical psychology for those experiencing psychological distress has been highlighted previously in the ICU cohort and remains essential in the COVID-19 population (GPICS 2019). Considerations of late sequelae of mental health issues such as anxiety should also be considered by the MDT in the rehabilitation and follow up clinic phases.

Recovery of Laryngeal Function - ICU Treatment Options

Facilitating Laryngeal Airflow

For tracheostomised patients, cuff deflation followed by placement of a one way valve provides increased Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP), upper airway sensation and restoration of the ability to verbally communicate. Evaluation of one-way valve tolerance and resultant voice quality by SLTs enables the multidisciplinary team to be aware of any potential laryngeal impairments. Intensivists, nurses, psychologists, dietitians and physiotherapists may all utilise the one-way valve during their interactions with the patient, restoring the opportunity for verbal communication between the clinician and the patient. The use of a one way valve by the patient during video calls to family members who have been unable to remain at the bedside has been highlighted as a significantly positive experience by patients, families and staff alike during the pandemic.

Use of the one-way valve may also contribute to dysphagia rehabilitation, with improvement to sensory awareness of any aspiration of oral intake (ICS NTSP 2020; Suiter et al. 2003). Any residual vocal cord impairments should be identified early in the management of tracheostomised patient to inform decannulation decisions. Anecdotally, for COVID-19 patients, the authors have observed patient-reported larygopharyngeal hypersensitivity and reduced tolerance of one-way valve application. This may be due to a range of factors; laryngeal oedema, breathlessness and tachypnoea (McGrath et al. 2020). Impaired laryngeal sensation, secretion clearance and cough strength/sensitivity all delay ventilator and tracheostomy weaning and decannulation (Garuti et al. 2014).

For those unable to tolerate one way valve application, Above Cuff Vocalisation (ACV) may be carefully considered. Airflow is introduced via the subglottic port of the tracheostomy tube and has been shown to potentially restore laryngeal sensitivity, increase cough response to pooled laryngeal secretions and increase an airway protective response (McGrath et al. 2018). However, ACV is an AGP that requires balancing the associated risks. Inability for airflow to escape via an upper airway which is fully or partially obstructed may cause subcutaneous emphysema, evident in swelling of the neck and face. Potential contraindications for ACV include patients with occult laryngeal oedema or vocal cord palsy. Direct visualisation of the larynx using nasendoscopy or FEES to assess the safety of ACV would mitigate this risk. Reports of COVID-19 associated upper airway oedema have been identified and therefore close observation and careful evaluation is recommended for both one-way valve and ACV techniques (McGrath et al. 2020).

Dysphagia Rehabilitation in COVID-19 Critical Illness

Dysphagia in the critically ill impedes recovery and is associated with adverse outcomes (Schefold et al. 2017; Macht 2011). Post extubation dysphagia is common, with an incidence reported as between 40-60% in ICU patients, with 38% presenting with silent aspiration due to altered glottic and subglottic sensation (McIntyre et al. 2020). Initial guidance recommending the cessation of FEES for COVID-19 patients was borne out of concern regarding the nasopharynx being a known reservoir for high concentrations of the virus (Zou et al. 2020). Our understanding of the infectious period for COVID-19 patients is evolving, and the viral load of patients at the time of a FEES examination is likely to have declined, given that the initial intubation is likely to be up to 20-24 days after the onset of symptoms (McGrath et al. 2020; Bolton 2020). Rapid guidance has been developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to address the initial cessation of FEES, and following thorough review its use has been restored with additional protective measures in place (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapy [RCSLT] 2020; Zaga 2020; Herazo 2020). SLTs have also been exploring alternative adjuvant methods to support clinical decision-making for the assessment of upper airway and swallowing. An international working party of SLTs are currently evaluating the potential contribution of ultrasound to evaluate vocal cord function and airway patency, particularly for use in the ICU.

Lima et al. (2020) suggested that whilst those with COVID-19 remain intubated for longer, the number of rehabilitation sessions focusing on swallowing was fewer and patients appeared to return to oral intake sooner than the comparison cohort. The authors reiterate this finding, except in the presence of neurological complications and severe global weakness. Isolated cranial nerve impairment must also be considered, with a case study by Aoyagi et al. (2020) reporting glossopharyngeal and vagal neuropathy resulting in dysphagia. Tailored rehabilitation for dysphagia usually consists of swallowing exercises to target the physiological impairment identified on instrumental examination. These may include established rehabilitation exercises or newer equipment-based therapies such as Pharyngeal Electrical Stimulation (PES) and Expiratory Muscle Strength Training (EMST). PES is indicated for patients with sensory dysphagia, which is frequently the main component in laryngeal dysfunction in critical illness. Research in this population is in its early stages but indications are that it may be beneficial for return to oral intake (Wallace 2020). The use of compensatory strategies as directed by SLT can also support return to safe oral intake, including altering bolus size and delivery and diet and fluid modification.

Dysphonia Rehabilitation in COVID-19 Critical Illness

For those with persistent dysphonia, a multidisciplinary team approach is advisable. Though for the majority of extubated patients dysphonia is typically transient, up to 10-35% of patients may present with residual symptoms (Mota et al. 2012). In those with persistent dysphonia, surgical intervention for glottal insufficiency may be indicated following joint comprehensive assessment and evaluation by ENT surgeons and SLTs. Alterations to a person’s typical vocal quality may have implications for their vocational rehabilitation, and further justifies the need for careful consideration and validation for timely intervention.

Prolonged Rehabilitation Following COVID-19 Critical Illness

Rehabilitation Frameworks

The longer a patient remains in ICU, the greater the risk for long term and residual complications (Stam et al. 2020). Post intensive care syndrome (PICS) describes physical, cognitive and/or mental impairments in patients following critical illness, with these impairments persisting beyond the intensive care unit (Biehl and Sese 2020).

While data pertaining to the length of recovery for those who survive a COVID-19 related intensive care admission is still being collated, anecdotal experience across ICUs in the United Kingdom indicates a high proportion have significant residual impairments (RCSLT 2020). Multidisciplinary team pathways have previously been established for those recovering from intensive care admission (GPICS 2019; NICE 2014). During COVID-19 a national multi-professional collaborative led by the Intensive Care Society (ICS) developed a gold standard rehabilitation framework for assessing early rehabilitation needs post ICU (ICS 2020). Guidance on potential laryngeal, voice and swallowing sequelae, methods of screening using the PICUPS tool and a rehabilitation prescription tool are all embedded within the guidance. Now, more than ever, the need for a coordinated rehabilitation approach is essential (Biehl and Sese 2020; McGrath et al. 2020; Stam et al. 2020).

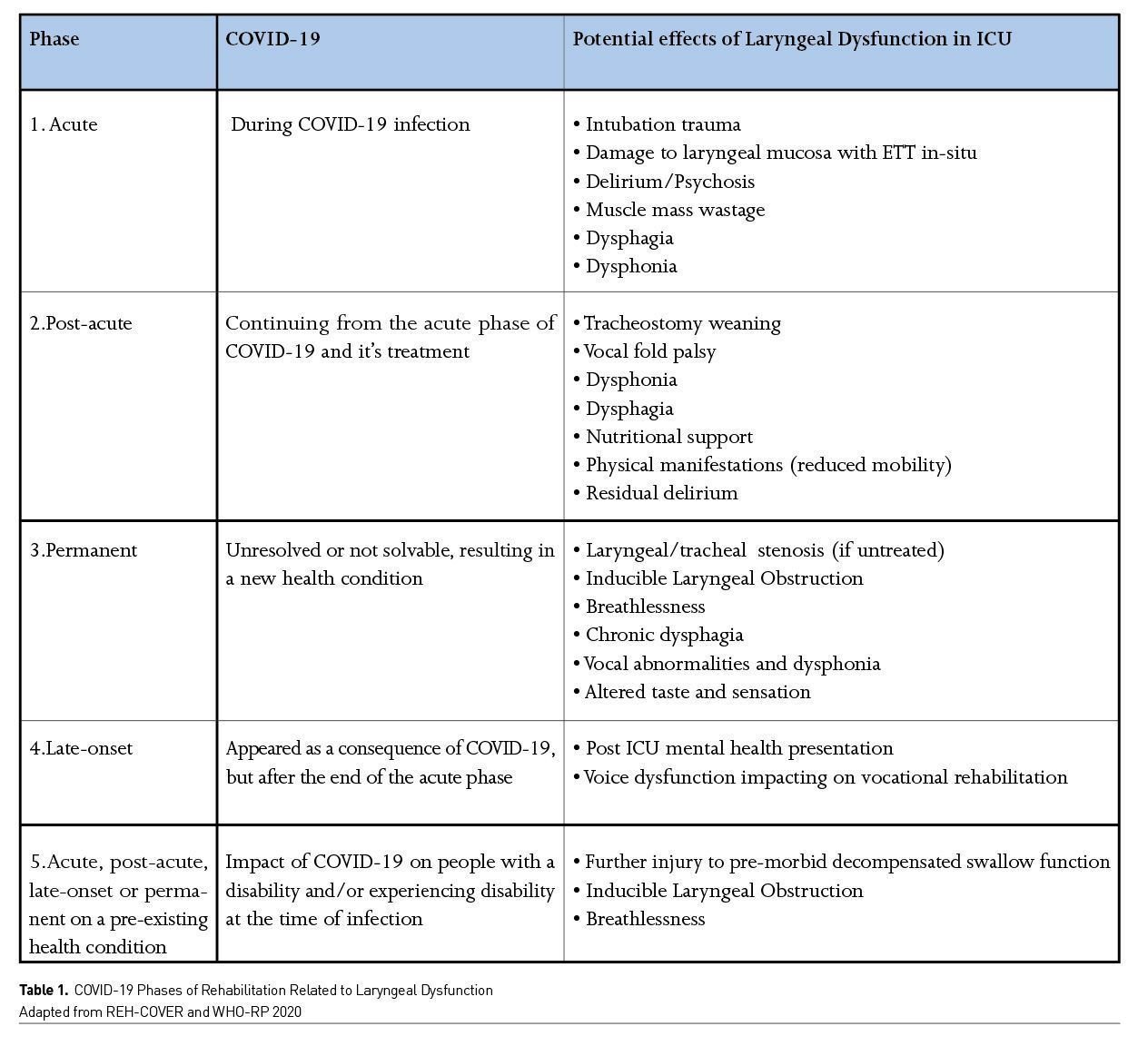

REH-COVER and WHO-RP have delineated proposed phases of COVID-19, which have been adapted below to serve as a guide when evaluating laryngeal dysfunction and it’s long term implications. Guidance on in-depth assessment by SLTs is also provided in ICS framework and the RCSLT documents (ICS 2020; RCSLT 2020).

Evaluation of the most appropriate rehabilitation pathway for COVID-19 patients at step-down from ICU to ward and from ward to discharge may be structured using the PICUPS tool (ICS 2020). The tool supports early detection of issues on ICU, triggers referral for specialist assessment and may also serve to include the patient in the ongoing assessment process.

ICU Follow-Up Clinics

Previous research has identified the potential for long term and residual complications of laryngeal injury (Brodsky et al. 2017). While published evidence on the long term effects of post COVID-19 laryngeal dysfunction is pending, the RCSLT have prepared an evaluation tool to guide clinicians running ICU follow up clinics in order to signpost those requiring additional intervention (RCSLT 2020). Persistent laryngeal dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, dysphonia, altered taste/sensation, breathlessness or chronic cough. Clinicians must also remain cognisant of laryngotracheal stenosis and inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) as potential aetiologies for long term airway and laryngeal dysfunction (Halvorsen et al. 2016).

Lessons Learned from Initial COVID-19 Peak

In the early stage of the pandemic, clinicians were advised to minimise the risk of AGPS. For these reasons, cuff deflation and application of a one-way valve (PMV) in-line with mechanical ventilation was delayed as was use of endoscopy for swallow assessment. Given our emerging knowledge regarding the reduction in the patient's viral load over time, once local risk assessments have been carried out, the treating team may wish to explore initiating these interventions at an earlier stage in the COVID-19 patient’s recovery.

The effect of PPE on ICU delirium has yet to be reported, however given anecdotal reports from patients the need for early facilitation of communication cannot be overemphasised. Early intervention by SLTs in critical care is needed now more than ever (GPICS 2 2019; NCEPOD 2014; ICS FICM 2020).

Recovery of laryngeal function may be prolonged and requires an integrated MDT approach. Patients being followed up by ICU outreach nurses and SLTs via telehealth have reported ongoing problems with voice, swallowing solid oral diets and taste alteration during the recovery phase. Further research is required to evaluate the nature of these residual impairments, to explore the unknown potential for residual SARS-Cov-2 pathogens in the larynx, and impact of prolonged intubation on laryngeal function in COVID-19 patients.

Conclusion

Early identification and consideration of laryngeal dysfunction in the ICU patient is essential to minimise further respiratory compromise and commence the patient on the most appropriate treatment. Laryngeal dysfunction impacts the wider ICU multidisciplinary team, given its impact on verbal communication, liberation from ventilation, respiratory function and nutrition. The role of the SLT is essential for robust assessment, diagnosis and management of laryngeal dysfunction and any consequent dysphagia or dysphonia and airway concerns. Whilst we await further research, evaluation of laryngeal dysfunction should remain a vital part of clinicians evaluations to promote optimal recovery post COVID-19.

Conflict of Interest

ZP has received honoraria for consultancy from GlaxoSmithKline, Lyric Pharmaceuticals, Faraday Pharmaceuticals and Fresenius-Kabi, and speaker fees from Orion and Nestle.

References:

Aoyagi Y, Ohashi M, Funahashi R, Otaka Y, Saitoh E (2020) Oropharyngeal Dysphagia and Aspiration Pneumonia Following Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Case Report. Dysphagia, 35(4):545-548. doi:10.1007/s00455-020-10140-z

Assessment of Swallowing After Prolonged Intubation in the ICU Setting. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 125(1):43-52. doi: 10.1177/0003489415596755

Biehl M, Sese D (2020) Post-intensive care syndrome and COVID-19 - Implications post pandemic. Cleve Clin J Med. doi:10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc055

Bolton L, Mills C, Wallace S, Brady M (2020) Aerosol generating procedures, dysphagia assessment and COVID‐19: A rapid review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 55(4):629-636. DOI: 10.1111/1460-6984.12544

Bonvento B, Wallace S, Lynch J, Coe B, McGrath BA (2017) Role of the multidisciplinary team in the care of the tracheostomy patient. J MultidiscipHealthc, 10:391-

398. doi:10.2147/jmdh.S118419

Brodsky MB, Levy MJ, Jedlanek E et al. (2018) Laryngeal Injury and Upper Airway Symptoms After Oral Endotracheal Intubation With Mechanical Ventilation During Critical

Care: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med, 46(12), 2010-2017.doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000003368

Brodsky MB, Pandian V, Needham DM(2020) Post-extubation dysphagia: a problem needing multidisciplinary efforts. Intensive Care Med 46, 93–96. doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05865-x

Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B et al. (2020) Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia, 75(6):785-799. doi:10.1111/anae.15054

El-Anwar, MW, Elzayat S, Fouad YA (2020) ENT manifestation in COVID-19 patients. Auris, nasus, larynx, S0385-8146(20)30146-2. Advance online publication.

doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2020.06.003

Ford DW, Martin-Harris B (2016) I Miss the Sound of Your Voice: Earlier Speech in Tracheostomy Patients. Crit Care Med, 44(6), 1234-1235.

Garuti G, Reverberi C, Briganti A et al. (2014). Swallowing disorders in tracheostomised patients: a multidisciplinary/multiprofessional

approach in decannulation protocols. Multidisciplinary respiratory medicine, 9(1), 36. doi.org/10.1186/2049-6958-9-36

Guidelines For The Provision of Intensive Care Services V2 (2019) Available from ficm.ac.uk/standards-research-revalidation/guidelines-provision-intensive-care-services-v2.

Halvorsen T., Walsted, E. S., Bucca et al. (2017). Inducible laryngeal obstruction: an official joint European Respiratory Society and European Laryngological Society statement. Eur Respir J, 50(3). doi:10.1183/13993003.02221-2016

Herazo J.V.; Starmer H.M.; Wallace S.; Bolton, L.; Seedat, J.; Madeira de Souza, C.; Freitas, S.V.; Skoretz, S.A.,. (2020). Assessment, diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a review of the literature and international guidelines. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 22 Sep 2020. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00163

Horby, P., Lim, W. S., Emberson, J. R., Mafham, M., Bell, J. L., Linsell, L.,Landray, M. J. (2020). Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

Intensive Care Society and FICM - Guidance for Tracheostomy Care (2020). Short-life Standards and Guidelines Working Party of the UK National Tracheostomy Safety Project.

https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-08-tracheostomy_care_guidance_final.pdf

Intensive Care Society, Responding to Covid-19 and beyond. A framework for assessing early rehabilitation needs following ICU (August 2020)

Intensive Care Society. (2014). Guidelines and standards for assessing early rehab needs following ICU.

Kortebein P, et al. (2018) Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(10):1076–1081. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1076.

Kotfis, K., Williams Roberson, S., Wilson, J. E., Dabrowski, W., Pun, B. T., & Ely, E. W. (2020). COVID-19: ICU delirium management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care,

24(1), 176. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-02882-x

Koukourikos, K., Tsaloglidou, A., &Kourkouta, L. (2014). Muscle atrophy in intensive care unit patients. Acta informatica medica : AIM : journal of the Society for Medical Informatics

of Bosnia & Herzegovina : casopisDrustva za medicinskuinformatikuBiH, 22(6), 406–410.

https://doi.org/10.5455/aim.2014.22.406-410

Krusciunas, GP., Langmore, SE, Gomez-Taborda, S., Fink, D., Levitt, J., McKeehan, J., McNally, E., Scheel, R., Rubio, A.C., Siner, J., Vojnik, R., Warner, H., White, D., Moss,M.(

2020) The association between endotracheal tube size and aspiration (during FEES) in acute

respiratory failure survivors. August 14, 2020 - Volume Online First - Issue - doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004554

Kwee, M. M., Ho, Y. H., &Rozen, W. M. (2015). The prone position during surgery and its complications: a systematic review and evidence-based guidelines. International surgery,

100(2), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00256.1

Lima, M., Sassi, F., Medeiros, G., Ritto, A., & Andrade, C. (2020). Preliminary results of a clinical study to evaluate the performance and safety of swallowing in critical patients with

COVID-19. Clinics, 75. doi:10.6061/clinics/2020/e2021

Liney, T., Dawson, R., Seth, R., Wallace et al. (2019). Anxiety levels amongst patients with tracheostomies. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 123(4), E504-E505

Lovato, A., de Filippis, C., &Marioni, G. (2020). Upper airway symptoms in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). American journal of otolaryngology, 41(3), 102474.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102474

Macht, M., Wimbish, T., Clark, B. J., Benson, A. B., Burnham, E. L., Williams, A., & Moss, M. (2011). Postextubation dysphagia is persistent and associated with poor outcomes in

survivors of critical illness. Crit Care, 15(5), R231. doi:10.1186/cc10472

McGrath B, Wallace S. (2014). The UK National Tracheostomy Safety Project and the role of speech and language therapists. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head Neck Surgery

22(3)

McGrath, B. A., Brenner, M. J., Warrillow, S. J., Pandian, V., Arora, A., Cameron, T. S., Feller-Kopman, D. J. (2020). Tracheostomy in the COVID-19 era: global and multidisciplinar guidance. Lancet Respir Med, 8(7), 717-725. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30230-7

McGrath, B. A., Wallace, S., & Goswamy, J. (2020). Laryngeal oedema associated with COVID-19 complicating airway management. Anaesthesia, 75(7), 972-972.

doi:10.1111/anae.15092

McIntyre, M., Doeltgen, S., Dalton, N., Koppa, M., & Chimunda, T. (2020). Post-extubation dysphagia incidence in critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Crit

Care. doi:10.1016/j.aucc.2020.05.008

Meng, L., Qiu, H., Wan, L., Ai, Y., Xue, Z., Guo, Q., . . . Xiong, L. (2020). Intubation and Ventilation amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: Wuhan's Experience. Anesthesiology, 132(6),

1317-1332. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000003296

Miles, A., McLellan, N., Machan, R.et al. (2018). Dysphagia and laryngeal pathology in post-surgical cardiothoracic patients. J Crit Care 45, 121-127. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.027

Mota, L. A., de Cavalho, G. B., & Brito, V. A. (2012). Laryngeal complications by orotracheal intubation: Literature review. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 16(2), 236-245. doi:10.7162/s1809-

97772012000200014

National Institute for Health Excellence and Care (2014). Rehabilitation after critical illness.NICE Clinical Guideline 83. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,

London,UK 2009.Availablefrom:http:/www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg83

Ng FK, Wallace S, Khallil U, McGrath BA. (2019) Duration of trans-laryngeal intubation before tracheostomy is associated with laryngeal injury when assessed using Fibreoptic

Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallow. British J of Anaesthesia, Vol. 123, Issue 3, e447.

Parry, S. M., & Puthucheary, Z. A. (2015). The impact of extended bed rest on the musculoskeletal system in the critical care environment. ExtremPhysiol Med, 4, 16.

doi:10.1186/s13728-015-0036-7

Paterson, R. W., Brown, R. L., Benjamin, L et al. (2020). The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. doi:10.1093/brain/awaa240

Piazza, C; Filauro, M; Dikkers, F.G.; Reza Nouraei, S.A.; Sandu, K; Sittel, C; Amin, M.A.; Campos, G; Eckel, H; Peretti, G.(2020) Long-term intubation and high rate of tracheostomy in

COVID-19 patients might determine an unprecedented increase in airwy stenoses: a call to action from the European Laryngological Society. Eur Arch of Oto-Rhino-Laryngol, epub: 06 June 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06112-6

Ponfick, M; Linden, R; Nowak, D.A. (2015). Dysphagia—A Common, Transient Symptom in Critical Illness Polyneuropathy, Critical Care Medicine: 43(2), 365-372 doi:

10.1097/CCM.0000000000000705

RCSLT COVID-19 Speech and language therapy rehabilitation pathway: Part of the Intensive Care Society Rehabilitation Framework, developed by the Working Party. Deep dive speech and language therapy section. 14th July 2020

Royal College of Speech and Language Therapy (2020). Speech and Language Therapist-Led

Endoscopic Procedures in the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Scheel, R., Pisegna, J. M., McNally, E et al. (2017). Dysphagia in Mechanically Ventilated ICU Patients (DYnAMICS): A Prospective Observational Trial. Crit Care Med, 45(12), 2061-2069. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000002765

Stam, H. J., Stucki, G., &Bickenbach, J. (2020). Covid-19 and Post Intensive Care Syndrome: A Call for Action. J Rehabil Med, 52(4), jrm00044. doi:10.2340/16501977-2677

Suiter, D. M., McCullough, G. H., & Powell, P. W. (2003). Effects of cuff deflation and one-way tracheostomy speaking valve placement on swallow physiology. Dysphagia, 18(4), 284-

292. doi:10.1007/s00455-003-0022-x

Tadié, J. M., Behm, E., Lecuyer, L.et al. (2010). Post-intubation laryngeal injuries and extubation failure: a fiberoptic endoscopic study. Intensive Care Med, 36(6), 991-998. doi:10.1007/s00134-010-1847-z

Wallace

S and McGrath BA. (2020) Laryngeal complications after tracheal intubation and

tracheostomy: a multi-disciplinary approach. Brit J Anesth Ed (commissioned

article accepted for publication Sept 2020)

Wallace,

S; Sloan, L; Knight, S; McGrath, B; Templeton, R. (2020) Efficacy of pharyngeal

electrical stimulation treatment (PES) for dysphagia in critical care patients.

Dysphagia 35;173-174

Williamson, E. J., Walker, A. J., Bhaskaran, K., Bacon, S., Bates, C., Morton, C. E.,Goldacre, B. (2020). Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY.

Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4

Zaga, C., Pandian, V., Brodsky, M., Wallace, S., Cameron, T., Chao, C., Orloff, L., Atkins, N., McGrath, B.A., Lazarus, C., Vogel, A., Brenner, M. (2020) Speech-Language Pathology

Guidance for Tracheostomy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Multidisciplinary Perspective American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology DOI:

10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00089

Zang, X., Wang, Q., Zhou, H., Liu, S., Xue, X., & Group, C.-E. P. P. S. (2020). Efficacy of early prone position for COVID-19 patients with severe hypoxia: a single-center prospective

cohort study. Intensive care medicine, 1-3. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06182-4

Zhao, W. T., Yang, M., Wu, H. M., Yang, L., Zhang, X. M.,

& Huang, Y. (2018). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between

Sarcopenia and Dysphagia. J Nutr

Health Aging, 22(8), 1003-1009. doi:10.1007/s12603-018-1055-z

Zou, L., Ruan, F., Huang, M., Liang, L., Huang, H., Hong, Z., . . . Wu, J. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med, 382(12),

1177-1179. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001737