ICU Management & Practice, Volume 16 - Issue 4, 2016

This review article focuses on research-based advances in pain assessment practices in intensive care units (ICUs), and stresses clinician consideration of multimodal analgesic techniques for pain management in ICUs.

Over the past 30 years, attention devoted to pain experienced by intensive care unit (ICU) patients has evolved from recognising pain as co-existing with ICU illness and treatment (Puntillo 1990) to development of research-based guidelines to support assessment and treatment of pain (DAS-Taskforce 2015; Barr et al. 2013; Celis- Rodriguez et al. 2013). Guidelines recommend that monitoring pain in all ICU patients be a routine part of practice through use of subjective (self-report) or objective (behavior observation) pain assessment scales validated for ICU use. Furthermore, guidelines promote the use of analgesic interventions customized to the individual patient (DAS-Taskforce 2015). While opioids are identified in the guidelines as being the preferential analgesic (Barr et al. 2013), there is an ever-growing emphasis on use of multimodal analgesia. The purpose of this review is to address recent advances in ICU pain assessment and to discuss ICU pain management that emphasises analgosedation and multimodal analgesia, while identifying areas needing further attention.

ICU Pain Assessment

Evaluating pain intensity and pain behaviours prepares ICU practitioners to intervene and relieve patient suffering. A visually enlarged 0–10 linear numeric rating scale (NRS) has been determined to be the most valid and reliable self-report pain intensity scale for use with ICU patients (Chanques et al. 2010). Two pain behaviour scales were identified (Barr et al. 2013) to be the most valid and reliable for monitoring pain in medical, surgical, and non-brain injured trauma patients unable to self-report: the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) (Payen et al. 2001) and the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) (Gélinas et al. 2006). When compared recently in a mixed adult ICU, the CPOT had greater discriminant validation than the BPS (Rijkenberg et al. 2015). However, Chanques and colleagues (Chanques et al. 2014) compared these scales as well as a third behaviour scale, the Non-Verbal Pain Scale (NVPS). They found the psychometric properties to be similar between the BPS and CPOT and better than the NVPS, and the BPS was rated as easiest to use. Until further research determines otherwise, clinicians can be comfortable using either the CPOT or BPS for many types of patients in their ICU.

However, there are a few patient group exceptions. Until recently, there was little guidance on the use of the CPOT or BPS in ICU patients with delirium. Kanji and colleagues (2016) tested the psychometric properties of the CPOT on 40 delirious positive [i.e., Confusion Assessment Method-ICU (CAMICU)] (Ely et al. 2001) patients. Patients had multiple types of diagnoses and were noncomatose; 90% were mechanically ventilated. The patients were CPOT-tested during both painful and non-painful procedures, and the CPOT showed excellent validity and reliability. A modified version of the BPS was tested in 30 non-intubated, mostly delirious patients, who were unable to self-report their pain but could vocalise sounds, during both painful and non-painful procedures (Chanques et al. 2009). A “vocalisation” section was substituted for the “ventilator” section of the original BPS. The BPS-Non-Intubated (BPS-NI) showed excellent psychometric properties as well. Thus, clinicians now have a choice of two pain behaviour scales for assessing pain in their delirious patients.

Until recently there was also little guidance on the use of pain behaviour scales for brain-injured ICU patients. There is incipient evidence that traumatic brain-injured patients’ pain behaviours differ from other ICU patients, especially in relation to facial expressions ( Gélinas and Arbour 2009) and level of consciousness (Arbour et al. 2014). While this research shows promise, as well as research of pain behaviours in non-trauma-related brain injury (Echegaray-Benites et al. 2014; Wibbenmeyer et al. 2011), a pain behaviour scale for braininjured patients is not developed enough for adoption by ICUs. Research is also limited on pain behaviour scales for several other patient populations, since they were excluded from research studies: those with motor response limitations such as patients with quadriplegia or other spinal cord injuries, patients with burn injuries, especially to the face, patients with a history of chronic pain or chronic substance abuse, those receiving neuromuscular blocking agents, and patients with dementia or other cognitive deficits (Chanques et al. 2009; Gélinas and Arbour 2009; Payen et al. 2001; Puntillo et al. 2014b; Helfand and Freeman 2009). Regarding ICU patients with cognitive deficits, until further research is conducted on pain assessment methods for them, clinicians can use research findings from non-ICU settings. For example, patients with cognitive impairment may be able to accurately report pain. Those who are markedly cognitively impaired report less intense pain and have a smaller number of pain complaints than those mildly impaired. However, cognitively impaired patients will report pain, if present, when specifically asked, and many can understand some self-assessment scale such as the NRS or a verbal rating scale. Unfortunately, cognitively impaired patients are less likely to ask for and receive analgesics, and providers underestimate their pain (Helfand and Freeman 2009; Buffum et al. 2007).

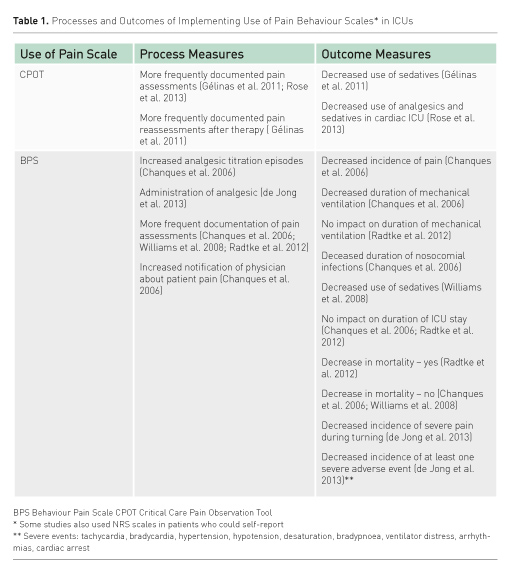

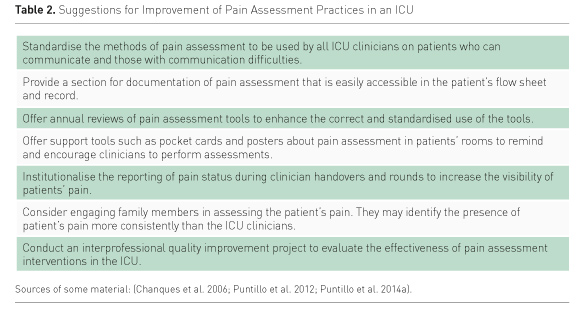

Important to ICU clinicians is that use of pain behaviour tools in patients unable to selfreport has been shown to improve the processes of pain assessment as well as patient outcomes. Table 1 presents the effects of CPOT or BPS use as a result of unit-based pain education programmes. However, in spite of this work, some challenges remain to be addressed in order for patients to reap the benefits of pain assessment practices in ICUs. Rose and colleagues (Rose et al. 2012) found, from 802 ICU nurse surveys, that only 33% of the nurses used a pain assessment tool if patients were unable to communicate. In only 74% of the surveys was the use of behavioural assessment tools noted to be moderately to extremely important. Having pain assessment tools available for clinicians and having a pain assessment protocol in place have been associated with greater odds of tools being used in practice.(Rose et al. 2012) Table 2 offers suggestions for improvement of pain assessment practices in an ICU.

ICU Pain Management

Management of pain is not only a humane approach to the care of ICU patients; adequate pain management helps prevent both shortterm and long-term morbidities from increased physiological and psychological stress(Sigakis and Bittner 2015). Currently, there is increased support for two approaches to pain management in ICU patients: analgosedation and multimodal analgesia.

Analgosedation

Analgosedation refers to the use of analgesics before sedatives in order to focus first on pain relief. An “analgesia first” approach to pain management is recommended for patients who may be demonstrating agitation and restlessness as well as pain behaviours and/or for patients that have identifiable, potential causes of pain (Barr et al. 2013; Devabhakthuni et al. 2012). Using analgesics first may also lead to the use of lighter sedation resulting in more awake, responsive patients and better clinical outcomes such as shorter mechanical ventilation and ICU stay durations (Devabhakthuni et al. 2012). Devabhakthuni and colleagues (2012) present a critical evaluation of analgosedation studies. They concluded that, despite limitations of the research to date, analgosedation can focus on patient outcomes while providing pain relief. For example, use of an analgosedation protocol in a neurointensive care unit demonstrated the protocol to be feasible in this patient population with unique needs such as strict control of mean arterial, cerebral perfusion and intracranial pressures (Egerod et al. 2010).

Multimodal Analgesia

The second recommended approach to ICU pain management is use of multimodal analgesia, which often includes opioid use. Use of intravenous (IV) opioids as the first-line approach to pain management in the ICU is supported by recent guidelines (Barr et al. 2013). The most commonly used opioids are morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and remifentanil. Reviews exist that compare opioids’ mechanisms of action, side-effect profiles, and recommended dosing regimens (Trescot et al. 2008; Erstad et al. 2009; Lindenbaum and Milia 2012). Comparison of IV remifentanil to fentanyl in ICU patients found those drugs to be equianalgesic (Spies et al. 2011). An advantage of remifentanil is that it has a faster onset, shorter half life, and is not metabolised by the liver or kidneys (Sigakis and Bittner 2015). An IV remifentanil-based intervention for sedation compared to a midazolam-based intervention tested in a random sample of medical-surgical ICU patients on long-term mechanical ventilation (i.e. longer than 96 hours) showed that the former was associated with better outcomes: shorter mechanical ventilation duration, shorter weaning-to-extubation time, and shorter offset of medication effect when discontinued (Breen et al. 2005). There were similar findings in a sample of ICU neurotrauma or neurosurgery patients when a primarily remifentanil regimen was compared to a primarily hypnotic (propofol) regimen (Karabinis et al. 2004). However, remifentanil is more frequently associated with secondary hyperalgesia after its withdrawal as an analgesic agent (Angst et al. 2003; Joly et al. 2005) and is more expensive (Sigakis and Bittner 2015). All opioids should be used cautiously due to their well-known potential adverse effects (Erstad et al. 2009). Of additional concern is the possible development of opioid tolerance (Dumas and Pollack 2008), opioid-induced hyperalgesia (Wachholtz et al. 2015) and opioid withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of opioids (Liatsi et al. 2009, Korak- Leiter et al. 2005). Another current concern is the ongoing opioid epidemic, especially in the United States (Rudd et al. 2016). However, while research-based data are limited on patient progression from acute-to-chronic opioid use after hospitalisation, this progression was not found in a recent study of post-ICU patients (Yaffe et al. 2015). Yet, this topic is in need of further study. In the meantime, patients’ pain relief should remain a high priority, with use of opioids continuing for patients in need.

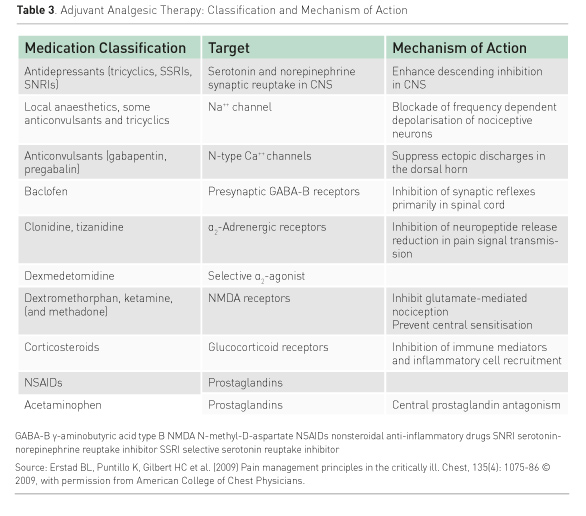

A multimodal analgesia approach to pain management, through the use of opioids and non-opioid analgesics as combination therapy, provides a balanced approach to analgesia (White and Kehlet 2010; Erstad et al. 2009). Advantages of multimodal therapy are that it is an opioid-sparing technique, which helps to avoid the adverse effects of, and possible negative sequelae from, opioid use. It promotes the use of smaller doses of each drug being used, and complements the drugs’ effects because of their different pharmacodynamics. Table 3 presents types of non-opioid agents and their mechanisms of action. Some of these agents, such as antidepressants, baclofen, and corticosteroids are not first-line medications used for pain in ICU due to their side-effect profiles, methods of administration, and/or long onset to effectiveness. However, they could be considered for an individual patient under special circumstances

Some of the other agents on Table 3, along with opioids, could more likely be part of a multimodal analgesia approach. Anaesthetic agents, alone or with opioids, are used in regional analgesia techniques (epidural, intrathecal, intercostal, femoral nerve) (De Pinto et al. 2015; Lindenbaum and Milia 2012). Nonopioids such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, acetaminophen, gabapentin, nefopam, dexmedetomidine, and paracetamol or acetaminophen can be considered for multimodal analgesia, according to the particular type of patient pain, mode of administration availability, and co-existing conditions (Payen et al. 2013; Chanques et al. 2011; Pandey et al. 2002). Finally, ketamine, a phencyclidine derivative, has both anaesthetic and analgesic properties (Lindenbaum and Milia 2012). IV infusions of ketamine used for analgosedation may decrease opioid consumption, reduce airway resistance, spare bowel motility, lower opioid tolerance, and prevent opioid hyperalgesia (Patanwala et al. 2015; Joly et al. 2005; Lindenbaum and Milia 2012; Erstad and Patanwala 2016). As a phencyclidine derivative, ketamine has potential psychotomimetic effects such as dysphoria, hallucinations, disorganized thinking and delirium. Use of lower doses may help to avoid these effects (Erstad and Patanwala 2016).

Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as the use of music, relaxation techniques, and/ or providing information about expectations during procedures can be considered part of multimodal analgesia (Erstad et al. 2009; Sigakis and Bittner 2015). While research is limited on the effectiveness of these techniques on pain relief, they are generally low-cost, safe, and relatively easy to implement. Further research is warranted on the role of nonpharmacologic interventions in multimodal analgesia.

Conclusions

The assessment and treatment of pain continue to be challenges for ICU clinicians. These challenges can be mitigated by adoption of wellvalidated pain assessment methods and a standardized organisational approach to assessment, documentation, and communication of patient pain among ICU team members. Applying the principle of “analgesia first” helps to assure that pain is treated before sedatives and hypnotics are introduced since analgesia may negate the need for other medications. Multimodal analgesia techniques accentuate the positive effects of a combination of opioids and non-opioids while minimising the adverse effects of both. Further research is necessary to demonstrate the beneficial effects of these approaches to pain assessment and treatment in heterogeneous groups of ICU patients.

Abbreviations

BPS Behavioral Pain Scale

BPS-NI Behavioral Pain Scale-Non-Intubated

CAM-ICU Confusion Assessment Method-ICU

CPOT Critical Care Pain Observation Tool

ICU intensive care unit

IV intravenous

NRS numeric rating scale

NVPS Non-Verbal Pain Scale

References:

Angst MS, Koppert W, Pahl I et al. (2003) Short-term infusion of the mu-opioid agonist remifentanil in humans causes hyperalgesia during withdrawal. Pain, 106(1-2): 49-57.

PubMed ↗

Arbour C, Choinière M, Topolovec-Vranic J et al. (2014) Detecting pain in traumatic brain-injured patients with different levels of consciousness during common procedures in the ICU: typical or atypical behaviors? Clin J Pain, 30(11): 960-9.

PubMed ↗

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K et al. (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med, 41(1): 263-306.

PubMed ↗

Breen D, Karabinis A, Malbrain M et al. (2005) Decreased duration of mechanical ventilation when comparing analgesia-based sedation using remifentanil with standard hypnotic-based sedation for up to 10 days in intensive care unit patients: a randomised trial [ISRCTN47583497]. Crit Care, 9(3): R200-10.

PubMed ↗

Buffum MD, Hutt E, Chang VT et al. (2007) Cognitive impairment and pain management: review of issues and challenges. J Rehabil Res Dev, 44(2): 315-30.

PubMed ↗

Celis-Rodriguez E, Birchenall C, De La Cal MÁ et al. (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for evidence-based management of sedoanalgesia in critically ill adult patients. Med Intensiva, 37(8): 519-74.

PubMed ↗

Chanques G, Jaber S, Barbotte E et al. (2006) Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med, 34(6): 1691-9.

PubMed ↗

Chanques G, Payen JF, Mercier G et al. (2009) Assessing pain in non-intubated critically ill patients unable to self report: an adaptation of the Behavioral Pain Scale. Intensive Care Med, 35(12): 2060-7.

PubMed ↗

Chanques G, Pohlman A, Kress JP et al. (2014) Psychometric comparison of three behavioural scales for the assessment of pain in critically ill patients unable to self-report. Crit Care, 18(5): R160.

PubMed ↗

Chanques G, Sebbane M, Constantin JM et al. (2011) Analgesic efficacy and haemodynamic effects of nefopam in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth, 106(3): 336-43.

PubMed ↗

Chanques G, Viel E, Constantin JM et al. (2010) The measurement of pain in intensive care unit: comparison of 5 self-report intensity scales. Pain, 151(3): 711-21.

PubMed ↗

DAS-Taskforce (2015) Evidence and consensus based guideline for the management of delirium, analgesia, and sedation in intensive care medicine. Revision 2015 (DAS-Guideline 2015) - short version. Ger Med Sci, 13, Doc19.

PubMed ↗

de Jong, A, Molinari N, de Lattre S et al. (2013) Decreasing severe pain and serious adverse events while moving intensive care unit patients: a prospective interventional study (the NURSE-DO project). Crit Care, 17(2): R74.

PubMed ↗

De Pinto M, Dagal A, O’Donnell B et al. (2015) Regional anesthesia for management of acute pain in the intensive care unit. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci, 5(3): 138-43.

PubMed ↗

Devabhakthuni S, Armahizer MJ, Dasta JF et al. (2012) Analgosedation: a paradigm shift in intensive care unit sedation practice. Ann Pharmacother, 46(4): 530-40.

PubMed ↗

Dumas EO, Pollack GM (2008) Opioid tolerance development: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic perspective. AAPS J, 10(4): 537-51.

PubMed ↗

Echegaray-Benites C, Kapoustina O, Gélinas C (2014) Validation of the use of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) with brain surgery patients in the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs, 30(5): 257-65.

PubMed ↗

Egerod I, Jensen MB, Herling SF et al. (2010) Effect of an analgo-sedation protocol for neurointensive patients: a two-phase interventional non-randomized pilot study. Crit Care, 14(2): R71.

PubMed ↗

Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J et al. (2001) Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med, 29(7): 1370-9.

PubMed ↗

Erstad BL, Patanwala AE (2016) Ketamine for analgosedation in critically ill patients. J Crit Care, 35, 145-9.

PubMed ↗

Erstad BL, Puntillo K, Gilbert HC et al. (2009) Pain management principles in the critically ill. Chest, 135(4): 1075-86.

PubMed ↗

Gélinas C, Arbour C (2009) Behavioral and physiologic indicators during a nociceptive procedure in conscious and unconscious mechanically ventilated adults: Similar or different? J Crit Care, 24(4): 628.e7–628.e17.

PubMed ↗

Gélinas C, Arbour C, Michaud C et al. (2011) Implementation of the critical-care pain observation tool on pain assessment/management nursing practices in an intensive care unit with nonverbal critically ill adults: a before and after study. Int J Nurs Stud, 48(12): 1495-504.

PubMed ↗

Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA et al. (2006) Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care, 15(4): 420-7.

PubMed ↗

Helfand M, Freeman M (2009) Assessment and management of acute pain in adult medical inpatients: a systematic review. Pain Med, 10(7): 1183-99.

PubMed ↗

Joly, V, Richebe P, Guignard B et al. (2005) Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia and its prevention with small-dose ketamine. Anesthesiology, 103(1): 147-55.

PubMed ↗

Kanji S, MacPhee H, Singh A et al. (2016) Validation of the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med, 44(5): 943-7.

PubMed ↗

Karabinis, A, Mandragos, K, Stergiopoulos, S, Komnos, A, Soukup, J, Speelberg, B. & Kirkham, A. J. 2004. Safety and efficacy of analgesia-based sedation with remifentanil versus standard hypnotic-based regimens in intensive care unit patients with brain injuries: a randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN50308308]. Crit Care, 8(4): R268-80.

PubMed ↗

Korak-Leiter M, Likar R, Oher M et al. (2005) Withdrawal following sufentanil/propofol and sufentanil/midazolam. Sedation in surgical ICU patients: correlation with central nervous parameters and endogenous opioids. Intensive Care Med, 31(3): 380-7.

PubMed ↗

Liatsi D, Tsapas B, Pampori S et al. (2009) Respiratory, metabolic and hemodynamic effects of clonidine in ventilated patients presenting with withdrawal syndrome. Intensive Care Med, 35(2): 275-81.

PubMed ↗

Lindenbaum L, Milia DJ (2012) Pain management In The ICU. Surg Clin North Am, 92(6): 1621-36.

PubMed ↗

Pandey CK, Bose N, Garg G et al. (2002) Gabapentin for the treatment of pain in Guillain-Barré syndrome: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Anesth Analg, 95(6): 1719-23.

PubMed ↗

Patanwala AE, Martin JR, Erstad BL. 2015. Ketamine for analgosedation in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. J Intensive Care Med, 41, 255-37.

PubMed ↗

Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL (2001) Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Critical Care Medicine, 29(12): 2258-63.

PubMed ↗

Payen JF, Genty C, Mimoz O et al. (2013) Prescribing nonopioids in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. J Crit Care, 28(4): 534 e7-12.

PubMed ↗

Puntillo K (1990) Pain experiences of intensive care unit patients. Heart Lung, 19)5 Pt 1): 526-33.

PubMed ↗

Puntillo K, Nelson JE, Weissman D et al. (2014a) Palliative care in the ICU: relief of pain, dyspnea, and thirst--a report from the IPAL-ICU Advisory Board. Intensive Care Med, 40(2): 235-48.

PubMed ↗

Puntillo KA, Max A, Timsit JF et al. (2014b) Determinants of procedural pain intensity in the intensive care unit. The Europain® study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 189(1): 39-47.

PubMed ↗

Puntillo KA, Neuhaus J, Arai S et al. (2012) Challenge of assessing symptoms in seriously ill intensive care unit patients: can proxy reporters help? Crit Care Med, 40(10): 2760-7.

PubMed ↗

Radtke F M, Heymann A, Franck M et al.(2012) How to implement monitoring tools for sedation, pain and delirium in the intensive care unit: an experimental cohort study. Intensive Care Med, 38(12): 1974-81.

PubMed ↗

Rijkenberg S, Stilma W, Endeman H et al. (2015) Pain measurement in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: Behavioral Pain Scale versus Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool. J Crit Care, 30(1): 167-72.

PubMed ↗

Rose L, Haslam L, Dale C et al. (2013) Behavioral pain assessment tool for critically ill adults unable to self-report pain. Am J Crit Care, 22(3): 246-55.

PubMed ↗

Rose L, Smith O, Gélinas C et al.(2012) Critical care nurses' pain assessment and management practices: a survey in Canada. Am J Crit Care, 21(4): 251-9.

PubMed ↗

Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE et al. (2016) Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths--United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 64(50-51): 1378-82.

PubMed ↗

Sigakis MJ, Bittner EA (2015) Ten myths and misconceptions regarding pain management in the ICU. Crit Care Med, 43(11): 2468-78.

PubMed ↗

Spies C, Macguill M, Heymann A et al. (2011) A prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study comparing remifentanil with fentanyl in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med, 37(3): 469-76.

PubMed ↗

Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M et al. (2008) Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician, 11(2 Suppl): S133-53.

PubMed ↗

Wachholtz A, Foster S, Cheatle M (2015) Psychophysiology of pain and opioid use: implications for managing pain in patients with an opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend, 146: 1-6.

PubMed ↗

White PF, Kehlet H (2010) Improving postoperative pain management: what are the unresolved issues? Anesthesiology, 112(1): 220-5.

PubMed ↗

Wibbenmeyer L, Sevier A, Liao J et al. (2011) Evaluation of the usefulness of two established pain assessment tools in a burn population. J Burn Care Res, 32(1): 52-60.

PubMed ↗

Williams TA, Martin S, Leslie G et al. (2008) Duration of mechanical ventilation in an adult intensive care unit after introduction of sedation and pain scales. Am J Crit Care, 17(4): 349-56.

PubMed ↗

Yaffe PB, Green RS, Butler MB et al. (2015) Is admission to the intensive care unit associated with chronic opioid use? a 4-year follow-up of intensive care unit survivors. J Intensive Care Med,doi: 10.1177/0885066615618189