Incentivising patients with tokenomics of health data

A cryptocurrency that represents the value of health information can motivate individuals

to make their health data shareable to those who are willing to pay for it.

Tokens are well established in the context of

Blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies.

It’s a digital asset that has a utility or a

payment function. Very often, it’s a hybrid token and

possesses both properties. However, technically, it

is just a piece of cryptographic code of no intrinsic

value. Although Blockchain and its related cryptocurrencies

are a recent development, tokens have been

the subject of psychological research for a long time.

In psychology, tokens are used to shape a target

behavior, and therefore tokens have to be backed by

reinforcers. A relation between a token of no intrinsic

value with an unconditioned reinforcer like food or

a conditioned one like money has to be established

by reinforcement. The law of effect (Thorndike 1898) describes that behaviour which is followed

by pleasant consequences as having a higher likelihood

of being repeated, whereas unpleasant consequences

decrease the likelihood of repeat behaviour.

The effectiveness of a token reward as a means of

behaviour modification has not only been observed

in humans but also in primates (Wolfe 1936) or

pigeons and rats (Skinner 1948; Skinner 1953). In humans,

it is often applied in cognitive behavioral therapy

and childrearing.

But how does that apply to health data and how

could the tokenisation of health data be the solution

of some of the most pressing problems in modern

healthcare?

Health data as the currency of healthcare

systems

Modern healthcare runs on data. Everybody is on

the hunt for data in order to optimise processes or develop better therapies. Tremendous amounts of

data are being generated by medical documentation,

regulatory requirements, and patient care (Raghupathi 2010). In addition, precision medicine and the

general trend of digitisation in healthcare lead to a

constant rise of data being gathered at the individual

user or patient’s level (Andreu-Perez et al, 2015;

HM Government UK 2014). Another driving force in

this massive growth of data is the individual himself

when using a fitness or wellness app.

There are only estimates what personal health

data are worth, but it can be deducted from what

companies are willing to invest in order to gather

those data. IBM bought Truven Health Analytics for

$2.6 billion to train Watson on 200 million patient

records, meaning that one record was worth 13 USD.

It is a low price if you take into account what pharmaceutical

companies invest in order to gather clinical

trial data and real-world evidence. Prices that

are being paid for so-called post-market surveillance

might be a good indicator of the data value, with an

average of €441 per patient paid to the physician

providing the data (Spelsberg et al 2017).

It is needless to say, that in today’s data economy, wherever there is a value generated out of data, it

is not the individual as a data provider who profits

directly from the monetisation of its data. It results

in a lack of incentives for individuals to demand or

record, digitise, and update their health data. Hence,

it perpetuates the current system of monopolisation

of health data leading to siloes and inefficiencies

instead of motivating the individual being in

control of his data.

Tokens as incentives to digitise health data

Most people are only interested in their health data

when they are sick or when somebody they know is

suffering from a health problem, but there are ways

to motivate them to tend to their health data. In a

recent survey in Switzerland, 43% of all people said

they would be willing to provide their personal data

to medical research, either for free or for a reduction

of their health insurance premium (Tagesanzeiger 2017). In comparison, 54% of internet users are

willing to share their health data with their health

insurance, if they receive incentives such as vouchers

or premium reduction (Statista 2015). However, 79%

of German online users want the power to decide

who can access their health data (BKK Dachverband

Gesundheitsreport 2016). It shows that healthcare

systems must incentivise individuals to take control

over their data. At the same time a technical infrastructure

is needed, where everybody who seeks data can ask individuals for their consent to make

their health data shareable.

A decentralised marketplace to tokenise

health data

Blockchain technology can facilitate such an infrastructure

in the form of a decentralised marketplace

where the access to health data is under the control

of the individual.

Information seekers can post their query and individuals

can remain anonymous and decide whether

or not they want to share their data. With the tokens

in a Blockchain-based marketplace, a reward can be

automatically transferred on the basis of a digital

contract once the data has been delivered. Such a

system has a clear advantage over a fiat currencybased

system where always a middleman has to be

involved and the large population of unbanked individuals

cannot participate.

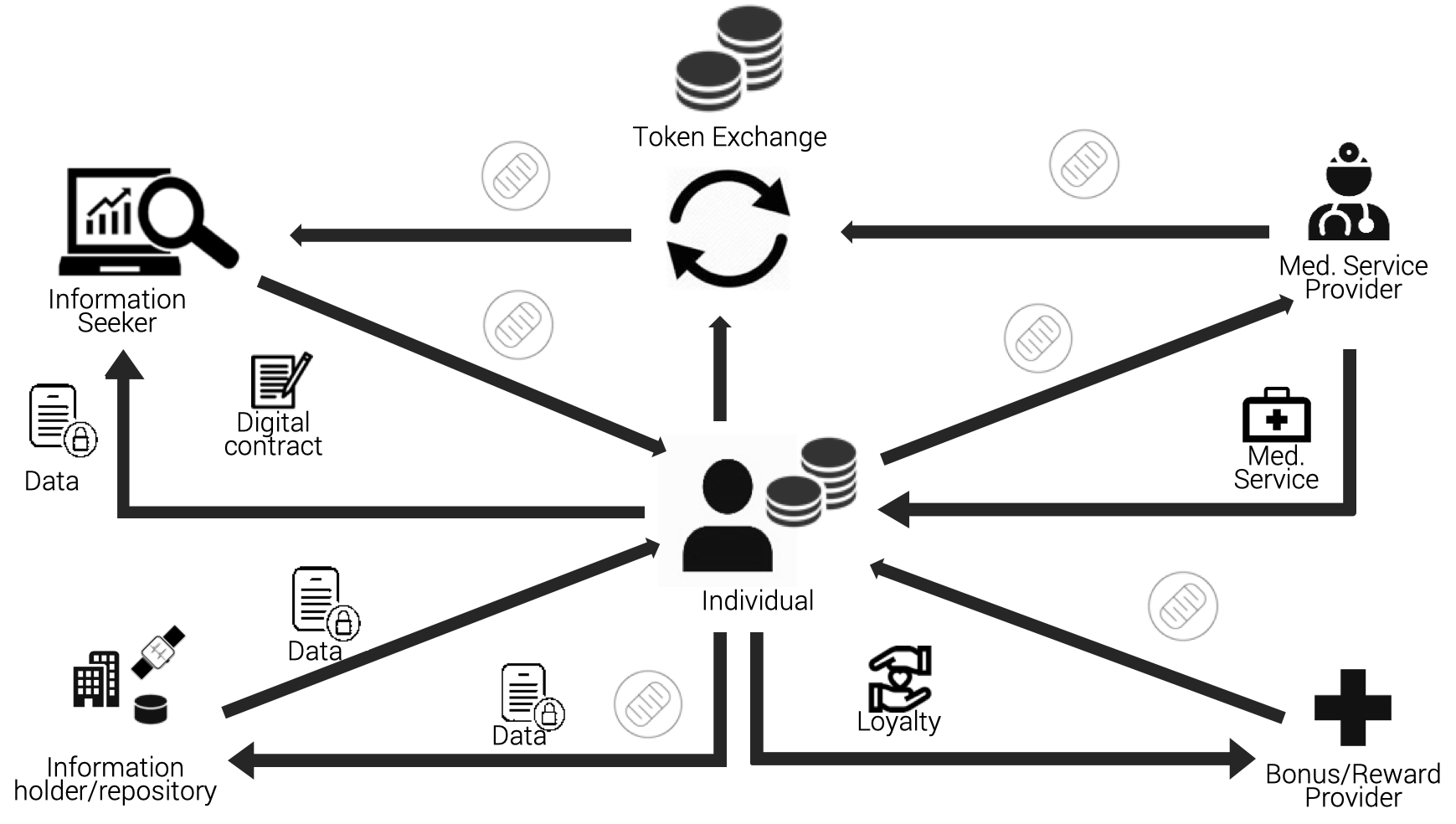

In Figure 1 the token economy of the Health

Information Traceability platform is presented. A

payment and utility token facilitates transactions

of health information. Information seekers acquire

tokens to incentivise individuals to digitise and share

their data, while individuals can: a) redeem bonuses/

services that are offered by service providers on the

platform; b) trade it for another cryptocurrency; or c)

exchange it for cash at designated exchanges. Individuals

can also monetise their data that is stored in external repositories and share revenues with the

information holders such as personal health records,

claims processing companies, hospitals and pharmacies.

The central asset to be exchanged in the

HIT-ecosystem is information that has a token value

attached to it. The token value depends on how

much the network participant values the information

in question.

Figure 1. HIT Token economy (HIT Foundation 2018)

Use cases for tokenising health information

• Research

Researchers have direct access to potential

study participants

• Population health data

Population survey and representative surveys

can be conducted via contacting individuals

directly

• Compliance Support

Individuals receive tokens when predefined health goals that are incorporated in a digital

contract are achieved.

Solutions with Blockchain-enabled

ecosystem

Such a distributed ecosystem can be implemented

with Blockchain technology, making transaction

processes transparent and more efficient at the

same time. A Blockchain-based token system is

predestined to align incentives among ecosystem

participants, for example, providers of health information

and those who want to analyse health data.

It allows the latter to have direct access to providers

of health information without the need for intermediaries.

At the same time, it puts individuals in

control of the use and monetisation of their health

data. Tokenisation of health data motivates individuals

to make their data shareable, thus solving

the fundamental problem of modern healthcare.

Key points

- Healthcare runs on huge volumes of data

- Value of health data varies

- Patients can be financially-incentivised to control their health data

- Blockchain technology can facilitate establishment of decentralised data marketplace

BKK Dachverband Gesundheitsreport 2016. Splendid Research.

HIT Foundation (2018) Whitepaper. Available from: hit.foundation/documents/Personalised Health and Care 2020, Framework for Action.

National Information Board HM Government UK (2014) Available from gov.uk/government/uploads/system/

uploads/attachment_data/file/384650/NIB_Report.pdf

Raghupathi W (2010) Data Mining in HealthCare. In Healthcare Informatics: Improving Efficiency and Productivity. Edited by Kudyba S. Taylor & Francis 211– 223.

Skinner, BF (1948) 'Superstition' in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology 38, 168-172.

Skinner, BF (1953) Science and human behavior. SimonandSchuster.

Spelsberg A, Prugger C., Doshi P, Ostrowski K., Witte T, Hüsgen D et al. (2017) Contributi on of industry funded postmarketing studies to drug safety: survey of notifications submit ed to regulatory agencies. BMJ 356:j 337

Statista (2015). Gesundheitsdateneine Fragedes Preises. Available from de.statista.com/infografik/3822/eebermittlung-elektronischer-gesundheitsdaten-fuer-verguenstigungen/

Tagesanzei ger (2017) So käuflichsind wir. Available from mobile2. tagesanzeiger.ch/articles/599ac823ab5c37

455e000001

Thorndike, EL (1898) Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals.

Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 2(4),i-109.

Wolfe, JB (1936) Effecti veness of token rewards for chimpanzees. Comparative Psychological Monographs 12, 1–72.

Figure 1. HIT Token economy (HIT Foundation 2018)

Figure 1. HIT Token economy (HIT Foundation 2018)

![Tuberculosis Diagnostics: The Promise of [18F]FDT PET Imaging Tuberculosis Diagnostics: The Promise of [18F]FDT PET Imaging](https://res.cloudinary.com/healthmanagement-org/image/upload/c_thumb,f_auto,fl_lossy,h_184,q_90,w_500/v1721132076/cw/00127782_cw_image_wi_88cc5f34b1423cec414436d2748b40ce.webp)