With ageing populations in Europe and North America, the number of elderly patients presenting to emergency departments with abdominal pain continues to rise. Individuals over 75 face unique diagnostic challenges due to atypical clinical presentations and the prevalence of serious underlying conditions. Computed tomography (CT) has become a cornerstone in diagnosing acute abdominal pathologies in this group, addressing diagnostic uncertainties and improving patient outcomes. A recent review published in Insights into Imaging explores the limitations of traditional diagnostic methods, common causes of acute abdomen in older patients and the critical role of CT in their evaluation.

Clinical and Biological Limitations in the Elderly

Diagnosing abdominal pain in elderly patients is complicated by several factors that impair the accuracy of anamnesis, physical examination, and laboratory tests. Cognitive impairments, such as dementia, sensory deficits, and altered mental states from medications or infections, frequently obscure patients’ histories. Older adults may not present with typical signs of infection or peritonitis; for example, fever and localised tenderness may be absent even in severe conditions. Chronic comorbidities, reduced muscle tone, and medications like beta-blockers further mask symptoms such as tachycardia or guarding.

Must Read: DL Harmonisation in Abdominal CT Imaging: Advancing Radiomics Reliability

In laboratory testing, inflammatory markers such as white blood cell count may not rise in the elderly, and liver function tests can appear normal in acute cholecystitis. Meanwhile, asymptomatic bacteriuria is common, particularly in institutionalised women, and may be misattributed as the cause of abdominal pain. These factors often lead to delayed or missed diagnoses, which contribute to higher morbidity and mortality rates in elderly patients. As a result, CT imaging is essential not only for detecting the source of abdominal pain but also for identifying silent yet life-threatening complications.

Prevalent Abdominal Pathologies in Older Adults

The distribution of abdominal pathologies varies significantly with age. In patients over 75, large bowel obstruction (LBO), ischemic events, and biliary disorders are more frequent than in younger cohorts. LBO is often caused by left-sided colorectal cancer, presenting with symptoms such as abdominal distension and altered bowel habits. Sigmoid volvulus, another form of LBO, is commonly seen in older adults with chronic constipation or neuropsychiatric disorders. CT imaging provides clarity by identifying the transition point and the “whirl” sign, crucial for surgical planning.

Bowel ischemia, particularly acute mesenteric ischemia and ischemic colitis, occurs with much greater frequency after age 80. CT findings—such as bowel wall thickening, decreased enhancement, pneumatosis, and mesenteric fat stranding—are vital for early diagnosis and treatment. Similarly, faecal impaction in elderly patients can lead to stercoral colitis, ischemia, or perforation, all of which are best detected through CT. Perforation due to foreign body ingestion or obstructive complications from urinary retention may also present atypically in the elderly, necessitating advanced imaging to guide intervention.

CT Imaging Protocols and Strategic Use in Emergency Departments

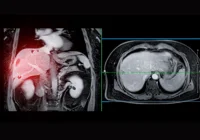

Given the limitations of clinical assessment and the high prevalence of complex conditions, CT scans are invaluable in emergency settings. However, contrast-enhanced CT carries risks, particularly in elderly patients with renal insufficiency. A practical strategy involves initially performing an unenhanced CT scan, followed by contrast-enhanced imaging only if necessary. This staged approach allows for evaluation of vascular calcifications, dense faecal masses, or foreign bodies while reducing the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

For suspected ischemia or when unenhanced CT yields inconclusive results, contrast is administered based on findings at the CT suite. Arterial phase imaging is especially important for diagnosing vascular causes such as mesenteric thrombosis. For colonic pathologies like uncomplicated diverticulitis or appendicitis with classic features, non-contrast CT may suffice. Yet, in many institutions, the need for workflow efficiency may necessitate immediate contrast-enhanced scans when radiologists cannot be present during the procedure.

CT protocols generally include imaging from the diaphragm to the pubic symphysis, with thin-slice reconstructions and multiplanar reformats to evaluate the extent and severity of pathology. Adjusting contrast volume to patient weight and timing arterial and portal phases appropriately enhances diagnostic accuracy, particularly in complex cases such as gangrenous cholecystitis or mesenteric ischemia.

Acute abdominal conditions in the elderly are more frequent, diverse, and complex than in younger populations. Traditional clinical assessments often fall short due to atypical presentations and comorbidities. CT imaging bridges this diagnostic gap, enabling accurate identification of life-threatening conditions and facilitating timely surgical or medical intervention. A personalised CT approach—balancing diagnostic accuracy with patient safety—should be integrated into emergency protocols for elderly patients. With appropriate triage and imaging strategies, outcomes for this vulnerable group can be significantly improved.

Source: Insights into Imaging

Image Credit: iStock