ICU Management & Practice, Volume 18 - Issue 4, 2018

Bedside ultrasound of the whole body

Bedside ultrasound, also known as point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), has been considered the new fifth pillar of physical examination (Narula et al. 2018) and is poised to replace the stethoscope. Based on its Greek etymology, the term “stethoscope” composed of stetho (breast) and scope (look into) may better suit miniaturised handheld ultrasound devices rather the tool invented by Laënnec in 1819 for auscultation. However, portable ultrasound devices have the ability to look beyond the chest. Therefore, the term “bodyscope” or whole-body ultrasound (WHOBUS) would more appropriately describe the potential of bedside ultrasound (Karabinis et al. 2010). It does not imply that the whole body should be examined every time, but rather that ultrasound can be used to complement clinical evaluation where indicated. Applications of ultrasound in the intensive care unit (ICU) are numerous, enabling simultaneous assessment of multiple organs. Two-dimensional (2D) or three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound offers a window into the anatomy of the patient, while haemodynamic physiology can be assessed using Doppler. In this article we describe current impact of the integration of WHOBUS into clinical care including specific clinical conditions that are common in the ICU and how WHOBUS can be used to identify the mechanism.

WHOBUS and the encephalopathic patient

Altered mental status in a critically ill patient requires consideration of a broad differential diagnosis, including various causes of intracranial hypertension, metabolic derangements and drug intoxication. The diagnostic approach requires careful history, physical examination, and complementary diagnostic investigations. Point-of-care neurologic ultrasound in the encephalopathic patient enables the critical care physician to rapidly detect life-threatening conditions including (but not restricted to) the presence of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) (Maissan et al. 2015; Lau and Arntfield 2017; Denault et al. 2018), midline shift from a space occupying lesion such as traumatic brain injury or stroke (Denault et al. 2018), and cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage (Denault et al. 2018). Furthermore, it can be used to confirm brain death (Ducrocq et al. 1998).

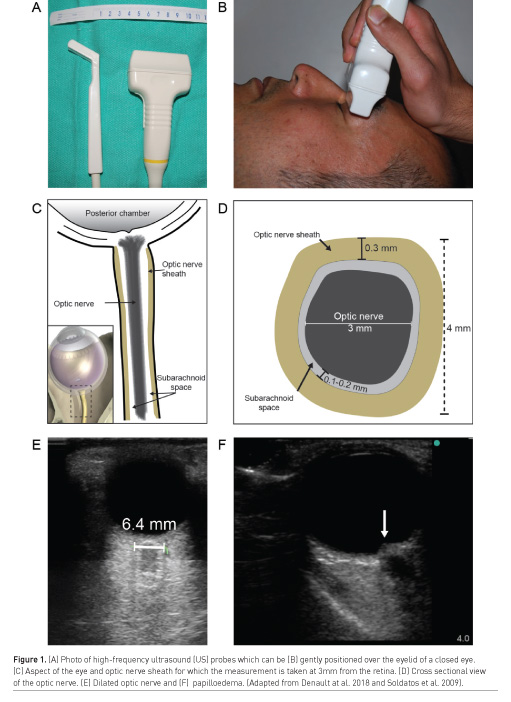

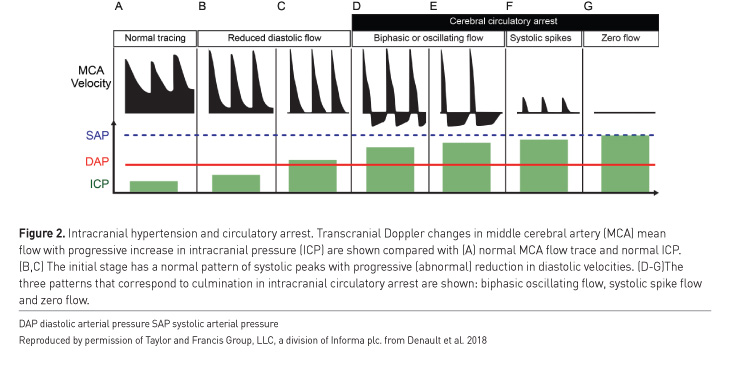

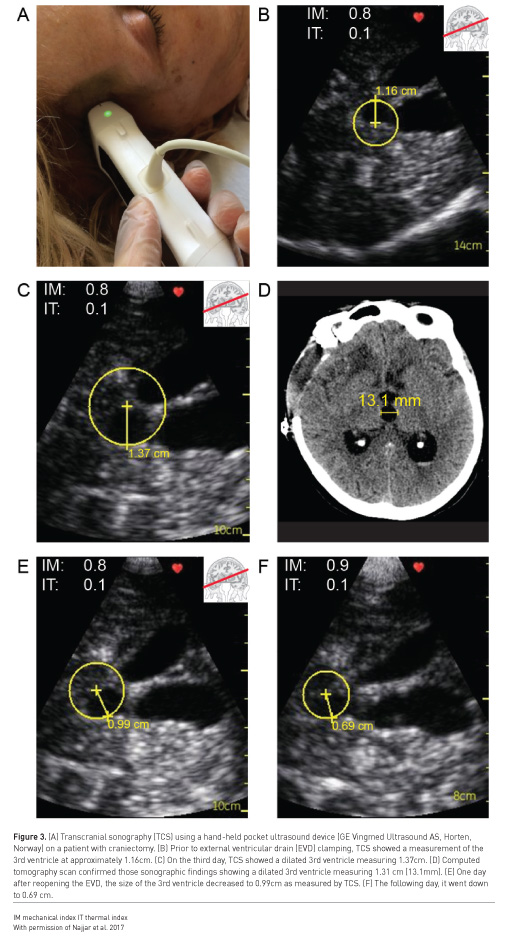

Examples of situations where point-of-care ultrasound may be useful in detection of intracranial hypertension include when invasive ICP monitoring is contraindicated (such as coagulopathy), or when a patient is too unstable to be transported for diagnostic imaging. Bedside intracranial pressure measurement with ultrasound is performed by placing a high frequency linear probe on the orbit to identify the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) (Figure 1). An ONSD > 5.0 mm predicts the presence of ICP > 20 mmHg with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 98% (Maissan et al. 2015), representing excellent diagnostic performance (area under the curve [AUC] of 0.99) (Maissan et al. 2015) (Figure 1). Serial ONSD measurements can be done to follow the progression of ICP. Intracranial hypertension may also be detected with ultrasound by measurement of blood flow velocity of the middle cerebral artery with spectral Doppler, known as transcranial colour-coded sonography (TCCS) (Lau and Arntfield 2017) (Figure 2). The pulsatility index (PI) is a Doppler-derived measure of the resistance to blood flow and is calculated as the difference between the peak systolic flow velocity and end-diastolic flow velocity, divided by the mean velocity. An elevated PI correlates with increased ICP, regardless of the nature of the intracranial pathology (Bellner et al. 2004). Typically a PI > 2.3 (normal PI value < 1.2) correlates with an ICP > 22 mmHg (Lau and Arntfield 2017). Presence of a midline shift of the cerebrum, a condition associated with ipsilateral intracranial hypertension, can also be detected by two-dimensional transcranial ultrasound. A transtemporal view of the third ventricle (Figure 3), a midline structure, is obtained and the distance to the middle of the third ventricle from the ipsilateral and contralateral edges of the cranium are measured; a discrepancy between the measured distances indicates presence of a midline shift (Denault et al. 2018).

An important caveat is that transcranial ultrasound requires an experienced operator, and even then is very difficult or impossible in up to 10% of patients (Denault et al. 2018). Detailed description of this technique is beyond the scope of this article but is well described elsewhere (Lau and Arntfield 2017; Denault et al. 2018).

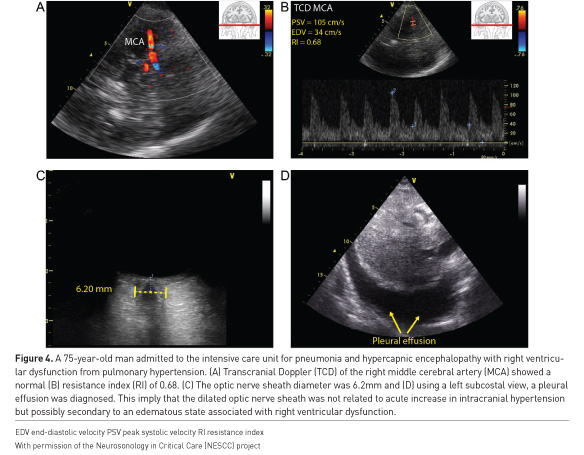

Finally, it is important to perform a systematic evaluation of the encephalopathic patient, as extra-cranial causes of altered mental status are numerous, such as cerebral congestion secondary to right heart dysfunction or volume overload (Figure 4), or cerebral hypoperfusion due to various causes of shock. WHOBUS can help identify the presence of these contributing pathologic states as we will describe in the following sections.

WHOBUS in the hypoxaemic patient

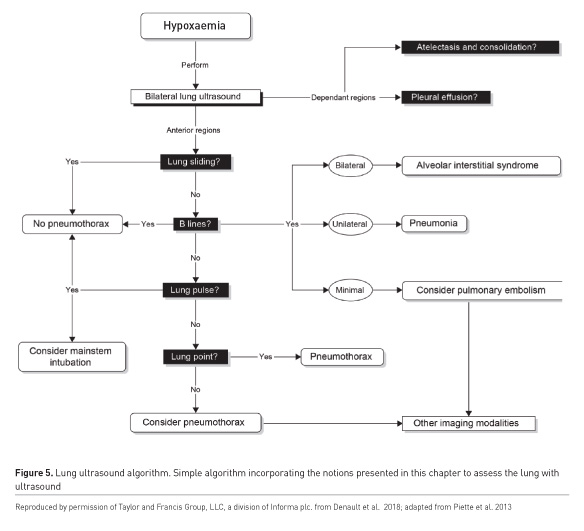

The approach to the hypoxaemic critically ill patient can be greatly simplified and enhanced with the use of point-of-care ultrasound (Piette et al. 2013). Lung and pleural ultrasound, as an adjunct to the clinical exam, can readily identify important causes of hypoxia and respiratory distress such as pulmonary oedema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothoraxes, pneumonia and pulmonary embolus.

The systematic, complete bilateral assessment of the chest allows the identification of key artefacts that are the result of the interplay between air, physiologic and pathologic tissue, pleura and fluid. When performed and interpreted correctly, the user can reach an accurate diagnosis, perhaps even obviating the need for other investigations such as chest radiography or computed tomography (Zanobetti et al. 2011; Volpicelli et al. 2008).

Numerous algorithms exist to direct users in the evaluation of the hypoxaemic patient (Figure 5), of which the BLUE protocol is probably the most well-known (Lichtenstein and Mezière 2008). The assessment begins with an examination of the anterior chest. The presence of lung sliding below the probe rules out a pneumothorax in that location. The absence of lung sliding does not enable a definitive diagnosis; however, a pneumothorax can still be ruled out by identifying a lung pulse in the pleura (fine oscillatory lung sliding from cardiac activity) or B lines, vertically projected pleural artefacts. Conclusive evidence of a pneumothorax can be identified by lung ultrasound by identification of a junction where areas of normal lung sliding and absent lung sliding meet the lung point (Zhang et al. 2006). Alveolar interstitial syndrome is identified if more than two B lines are seen in one intercostal space. Bilateral anterior B lines that have increased density in the dependent portions of the lung are characteristic of pulmonary oedema, where focal or skipped areas are more pathognomonic of pneumonitis or chronic interstitial disease respectively. A peripherally located focal lung consolidation could be a pulmonary embolus (Comert et al. 2013), which could be confirmed by detection of a deep venous thrombosis with ultrasound (Denault et al. 2018). Pleural effusion (Figure 4), consolidation and atelectasis (Lichtenstein et al. 2004) are usually found in the dependent lung regions. The volume of effusion can be estimated (Froudarakis 2008).

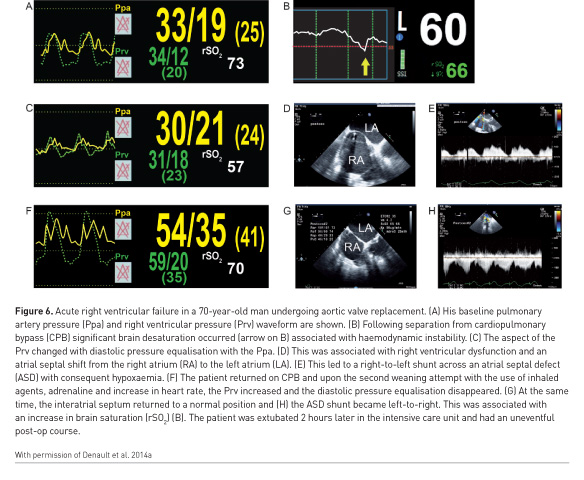

This modality is not without limitations, including the need for appropriate training, difficult imaging in obese patients or lung pathology that is very central with unaffected pleural boundaries (Mayo et al. 2009; Denault et al. 2018). In such a situation, a transoesophageal approach can be considered (Cavayas et al. 2016). However, in conjunction with WHOBUS of other relevant organ systems as well as conventional clinical tools, the diagnostic yield remains high and will likely grow in conjunction with user expertise (Denault et al. 2018). Lung ultrasound has surpassed the popularity of transthoracic echocardiography in many centres (Yang et al. 2016). In 5 to 10% of the time, hypoxaemia will be associated with normal lung ultrasound. In those conditions, a cardiac aetiology such as intracardiac shunt (Figure 6), obstructive pulmonary diseases or acute pulmonary embolism should be suspected.

WHOBUS in the haemodynamically unstable patient

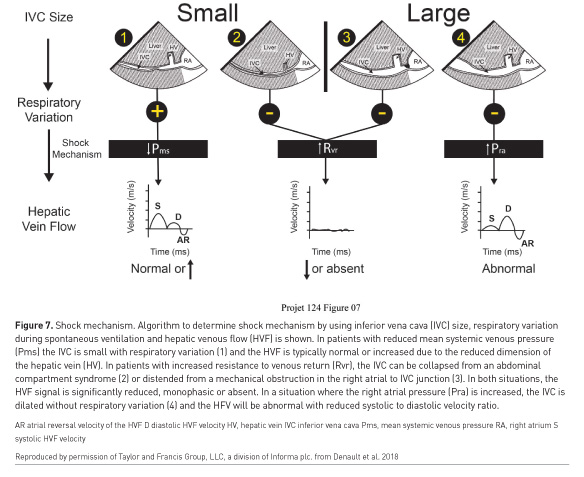

A reported method of using WHOBUS to assist in management in haemodynamic instability involves a two-step approach (Vegas et al. 2014; Denault et al. 2014b). The first is to identify the mechanism of haemodynamic instability (distributive, haemorrhagic, cardiogenic or resistive), using a combination of inferior vena cava (IVC) and hepatic venous flow (HVF) interrogation (Figure 7). The second step is to identify the aetiology.

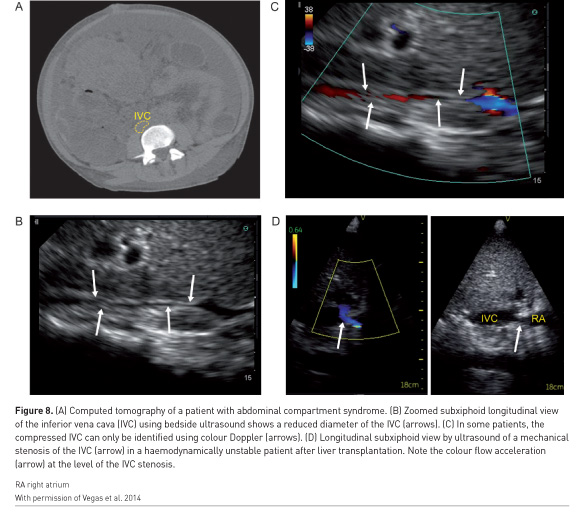

The initial step of identification of the mechanism of shock can be determined using the concept of venous return, which was popularised by Guyton et al. (1957). Haemorrhagic and distributive shock are typically associated with reduced systemic venous pressure. Cardiogenic shock is associated with an increase in right atrial pressure. Resistance to venous return can result from an infra-diaphragmatic obstruction such as abdominal compartment syndrome or a supra-diaphragmatic obstruction such as cardiac tamponade or tension pneumothorax. The IVC will be small in compartment syndrome (Figure 8A-C) and distended in tamponade. Rarely, IVC stenosis can occur after certain procedures such as liver transplantation (Figure 8D) and will be associated with a distended IVC with reduced ventricular cavities (Hulin et al. 2016). The hepatic venous flow will remain normal in shock states associated with preserved cardiac function (Figure 7, pattern 1) but will be abnormal when right ventricular dysfunction is present (Figure 7 pattern 3). However, in cases of resistance to venous return, absent or monophasic will be observed (Figure 7 pattern 2&3) (Beaubien-Souligny et al. 2018c).

A major advantage of WHOBUS over pressure and flow-based monitors is the ability of WHOBUS to be used to identify the aetiology of shock. Reduced venous systemic pressure from blood loss into the pleural and peritoneal spaces is readily detected with WHOBUS, but gastrointestinal bleeding and retroperitoneal bleeding are more difficult to detect. Septic shock will reduce venous systemic venous pressure through an increase in venous compliance. Many infective causes are detectable with WHOBUS, such as pneumonia, empyema, cholecystitis, pyelonephritis, bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis and endocarditis. Echocardiography is the gold standard for diagnosis of the aetiology of cardiogenic shock.

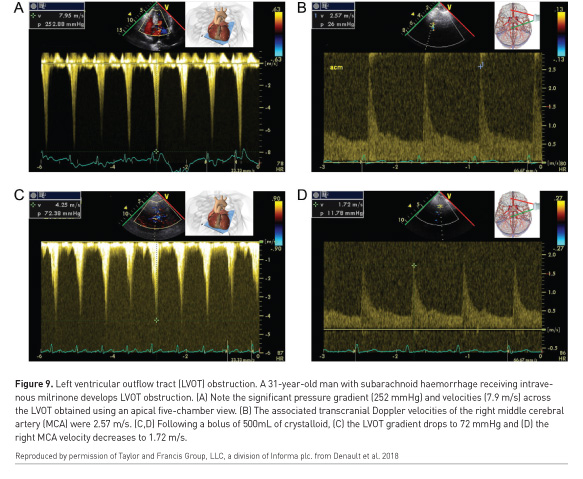

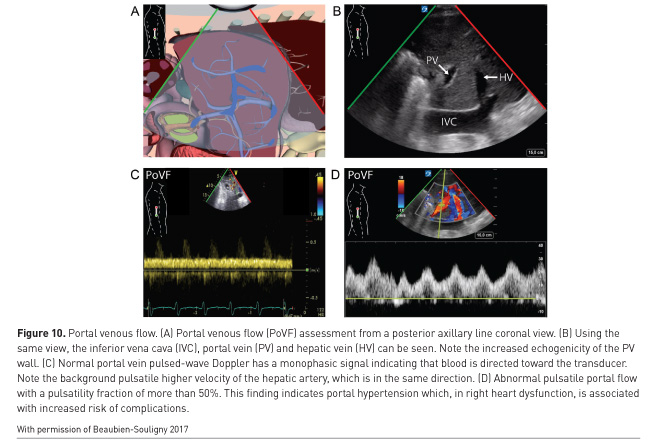

An important caveat is that two or more co-existing causes of haemodynamic instability may be present (Costachescu et al. 2002). In subarachnoid haemorrhage, myocardial depression can occur but also left ventricular outflow tract obstruction from the use of milrinone (Figure 9). In septic shock both left and right-sided myocardial depression can be present (Kimchi et al. 1984; Romero-Bermejo et al. 2011; Turner et al. 2011; Vallabhajosyula et al. 2017), which if missed, may result in excessive fluid overload (Andrews et al. 2017). As mentioned, pulmonary oedema is readily detected with WHOBUS (Beaubien-Souligny et al. 2017). Portal pulsatility (Figure 10) predicts both portal hypertension and complications after cardiac surgery (Eljaiek et al. 2018 In press), including renal failure (Beaubien-Souligny et al. 2018a).

WHOBUS in the oligo-anuric patient

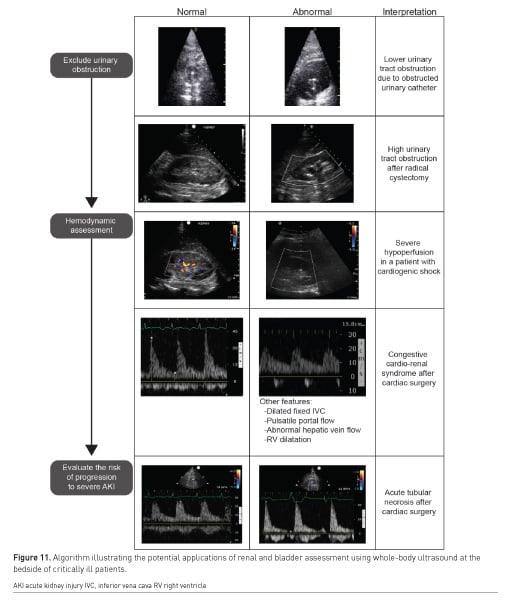

The approach to the critically ill patient with an acute reduction of urine output involves multiple aspects. These include the rapid recognition of reversible causes and the accurate identification of patients who will progress to severe acute kidney injury (AKI). A blind approach consisting of administration of fluids in an attempt to increase urine output is often ill-advised as renal fluid responsiveness is absent in 50% of oliguric critically ill patients and resulting fluid overload may lead to complications (Prowle et al. 2010). Urinary sodium measurements are ineffective in identifying responders (Legrand et al. 2016).

WHOBUS may be used as an adjunct to enhance the evaluation of the oligoanuric patient. A proposed approach is presented in Figure 11. WHOBUS can not only be used to identify both presence and level of renal obstruction and urine formation, fluid responsiveness but can also be used to determine renal hypoperfusion and extra-renal haemodynamic factors contributing to renal hypoperfusion. These concepts are beyond the scope of this short article.

Kidney and bladder ultrasound are enabling clinicians to rapidly screen for the possibility of lower or higher urinary tract obstruction. Lower urinary tract obstruction can occur frequently in critically ill patients because of urinary catheter dysfunction. Hydronephrosis may occur in the setting of urologic or other types of abdominal surgery (Narita et al. 2017) as well as retroperitoneal bleeding (Yumoto et al. 2018). After excluding urinary obstruction, Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess intra-renal blood flow velocities. Colour Doppler showing no signals in the renal parenchyma after adequate scale adjustments may offer a simple way to identify kidney hypoperfusion (Schnell and Darmon 2012; Barozzi et al. 2007; Schnell et al. 2014). The use of pulse-wave Doppler may have two applications. Arterial Doppler of the interlobar artery can identify patients with a highly abnormal resistive index (RI > 0.70). While this parameter is modified by numerous factors, a high RI has been demonstrated to be predictive of subsequent AKI or progression to severe AKI in critically ill patients and thus may be useful to identify which oliguric patients are the most concerning (Ninet et al. 2015). Venous Doppler at the level of the interlobar veins can assess whether alterations in intra-renal venous flow (periods of interrupted flow) are present (Iida et al. 2016; Nijst et al. 2017). The presence of severe alterations (venous flow present only in diastole) may suggest that venous hypertension is present and have a deleterious effect on kidney function, as it has been associated with AKI after cardiac surgery (Beaubien-Souligny et al. 2018b; 2018a).

The impact of WHOBUS

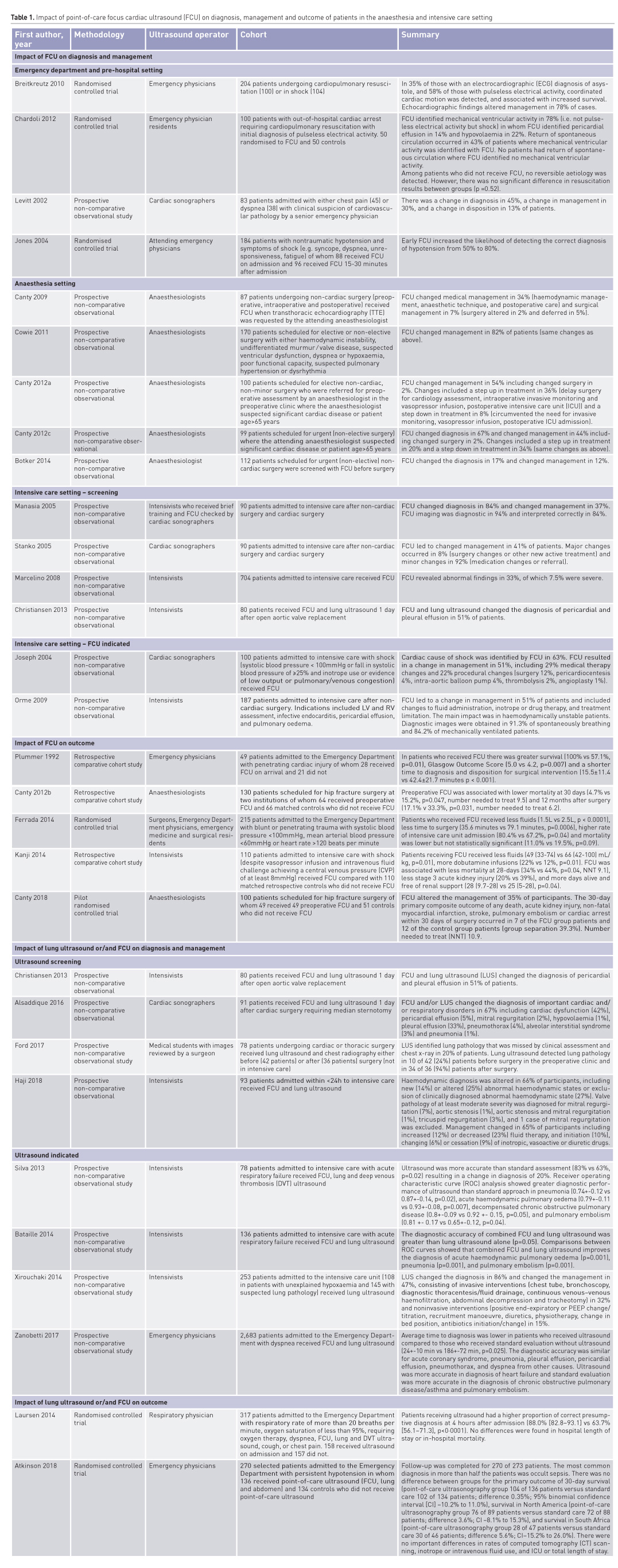

In order to explore the impact of WHOBUS, we performed a search based on a systematic review reported by Heiberg et al. (2016) with the aim of identifying the impact on diagnosis, management and outcome of POCUS in the emergency room, intensive care unit and the operating room. PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE electronic databases were searched using the following search terms: (“Echocardiography” OR “Ultrasonography”) OR “Heart Diseases/Ultrasonography” AND (“Perioperative Care” OR “Intensive Care” OR “Emergency Department”) AND (“Humans”). The references of each publication were searched for eligible publications. The search was restricted to peer-reviewed, original research, including prospective, retrospective cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies, but excluded systematic reviews, case reports, non-English language publications, studies published before 1 January 1995 or publications without the full text being available. Participants were humans aged at least 18 years. The intervention was focused echocardiography, lung ultrasound, abdominal ultrasound or deep venous thrombosis ultrasound performed either before, during or after non-cardiac surgery or in a critical care or emergency medicine setting. Outcomes included changes in clinical diagnosis, management, cardiac complications and death. For each individual publication, an outcome-level assessment of bias was performed that included the following parameters: patient selection, sonographer expertise, indication for surgery and indication for ultrasound. This bias assessment was considered in the synthesis of the result, but no scoring system was used. The impact on diagnosis, management and outcome of ultrasound of 2,020 patients are summarised in Table 1. Most studies were observational studies with few, randomised controlled trials. Changes in management and diagnosis range from 8% to 78%. Many of these studies have limited the use of ultrasound to the chest or the abdomen. There is a paucity of studies investigating whether an approach guided by ultrasound improves clinical outcomes. Consequently, there is an unmet need to design pragmatic trials to address these questions.

Conclusion

The clinical uses of ultrasound in critical care are increasing. Whole-body ultrasound is becoming a routine and useful tool for the critical care physician and is becoming incorporated into critical care training (Diaz-Gomez et al. 2017).

Conflict of interest

André Denault is on Speakers Bureau for CAE Healthcare and Masimo.

Abbreviations

AKI acute kidney injury

HVF hepatic venous flow

ICP intracranial pressure

ICU intensive care unit

IVC inferior vena cava

ONSD optic nerve sheath diameter

PI pulsatility index

POCUS point-of-care ultrasound

TCCS transcranial colour-coded sonography

WHOBUS whole-body ultrasound

References:

Alsaddique, A., A. G. Royse, C. F. Royse, A. Mobeirek, F. El Shaer, H. AlBackr, M. Fouda, and D. J. Canty. 2016. "Repeated Monitoring With Transthoracic Echocardiography and Lung Ultrasound After Cardiac Surgery: Feasibility and Impact on Diagnosis." Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 30 (2):406-12. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.08.033.

Andrews, B., M. W. Semler, L. Muchemwa, P. Kelly, S. Lakhi, D. C. Heimburger, C. Mabula, M. Bwalya, and G. R. Bernard. 2017. "Effect of an Early Resuscitation Protocol on In-hospital Mortality Among Adults With Sepsis and Hypotension: A Randomized Clinical Trial." JAMA 318 (13):1233-40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10913.

Atkinson, P. R., J. Milne, L. Diegelmann, H. Lamprecht, M. Stander, D. Lussier, C. Pham, et al. 2018. "Does Point-of-Care Ultrasonography Improve Clinical Outcomes in Emergency Department Patients With Undifferentiated Hypotension? An International Randomized Controlled Trial From the SHoC-ED Investigators." Annals of Emergency Medicine 72 (4):478-89. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.04.002.

Barozzi, L., M. Valentino, A. Santoro, E. Mancini, and P. Pavlica. 2007. "Renal ultrasonography in critically ill patients." Critical Care Medicine 35 (5 Suppl):S198-205. doi: 10.1097/01.Ccm.0000260631.62219.B9.

Bataille, B., B. Riu, F. Ferre, P. E. Moussot, A. Mari, E. Brunel, J. Ruiz, et al. 2014. "Integrated use of bedside lung ultrasound and echocardiography in acute respiratory failure: a prospective observational study in ICU." Chest 146 (6):1586-93. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0681.

Beaubien-Souligny, W., A. Benkreira, P. Robillard, N. Bouabdallaoui, M. Chasse, G. Desjardins, Y. Lamarche, M. White, J. Bouchard, and A. Denault. 2018a. "Alterations in Portal Vein Flow and Intrarenal Venous Flow Are Associated With Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study." J Am Heart Assoc 7 (19):e009961. doi: 10.1161/jaha.118.009961.

Beaubien-Souligny, W., J. Bouchard, G. Desjardins, Y. Lamarche, M. Liszkowski, P. Robillard, and A. Denault. 2017. "Extracardiac Signs of Fluid Overload in the Critically Ill Cardiac Patient: A Focused Evaluation Using Bedside Ultrasound." Canadian Journal of Cardiology 33 (1):88-100. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.08.012.

Beaubien-Souligny, W., R. Eljaiek, A. Fortier, Y. Lamarche, M. Liszkowski, J. Bouchard, and A. Y. Denault. 2018b. "The Association Between Pulsatile Portal Flow and Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study." Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 32 (4):1780-7. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.11.030.

Beaubien-Souligny, W., M. N. Pepin, L. Legault, J. F. Cailhier, J. Ethier, L. Bouchard, B. Willems, and A. Y. Denault. 2018c. "Acute Kidney Injury Due to Inferior Vena Cava Stenosis After Liver Transplantation: A Case Report About the Importance of Hepatic Vein Doppler Ultrasound and Clinical Assessment." Can J Kidney Health Dis 5:2054358118801012. doi: 10.1177/2054358118801012.

Bellner, J., B. Romner, P. Reinstrup, K. A. Kristiansson, E. Ryding, and L. Brandt. 2004. "Transcranial Doppler sonography pulsatility index (PI) reflects intracranial pressure (ICP)." Surgical Neurology 62 (1):45-51; discussion doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.12.007.

Botker, M. T., M. L. Vang, T. Grofte, E. Sloth, and C. A. Frederiksen. 2014. "Routine pre-operative focused ultrasonography by anesthesiologists in patients undergoing urgent surgical procedures." Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 58 (7):807-14. doi: 10.1111/aas.12343.

Breitkreutz, R., S. Price, H. V. Steiger, F. H. Seeger, H. Ilper, H. Ackermann, M. Rudolph, et al. 2010. "Focused echocardiographic evaluation in life support and peri-resuscitation of emergency patients: a prospective trial." Resuscitation 81 (11):1527-33. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.07.013.

Canty, D. J., J. Heiberg, Y. Yang, A. G. Royse, S. Margale, N. Nanjappa, D. Scott, et al. 2018. "Pilot multi-centre randomised trial of the impact of pre-operative focused cardiac ultrasound on mortality and morbidity in patients having surgery for femoral neck fractures (ECHONOF-2 pilot)." Anaesthesia 73 (4):428-37. doi: 10.1111/anae.14130.

Canty, D. J., and C. F. Royse. 2009. "Audit of anaesthetist-performed echocardiography on perioperative management decisions for non-cardiac surgery." British Journal of Anaesthesia 103 (3):352-8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep165.

Canty, D. J., C. F. Royse, D. Kilpatrick, L. Bowman, and A. G. Royse. 2012a. "The impact of focused transthoracic echocardiography in the pre-operative clinic." Anaesthesia 67 (6):618-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07074.x.

Canty, D. J., C. F. Royse, D. Kilpatrick, A. Bowyer, and A. G. Royse. 2012b. "The impact on cardiac diagnosis and mortality of focused transthoracic echocardiography in hip fracture surgery patients with increased risk of cardiac disease: a retrospective cohort study." Anaesthesia 67 (11):1202-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07300.x.

Canty, D. J., C. F. Royse, D. Kilpatrick, D. L. Williams, and A. G. Royse. 2012c. "The impact of pre-operative focused transthoracic echocardiography in emergency non-cardiac surgery patients with known or risk of cardiac disease." Anaesthesia 67 (7):714-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07118.x.

Cavayas, Y. A., M. Girard, G. Desjardins, and A. Y. Denault. 2016. "Transesophageal lung ultrasonography: a novel technique for investigating hypoxemia." Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 63 (11):1266-76. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0702-2.

Chardoli, M., F. Heidari, H. Rabiee, M. Sharif-Alhoseini, H. Shokoohi, and V. Rahimi-Movaghar. 2012. "Echocardiography integrated ACLS protocol versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest." Chinese Journal of Traumatology. Zhonghua Chuang Shang Za Zhi 15 (5):284-7.

Christiansen, L. K., C. A. Frederiksen, P. Juhl-Olsen, C. J. Jakobsen, and E. Sloth. 2013. "Point-of-care ultrasonography changes patient management following open heart surgery." Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal 47 (6):335-43. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2013.859294.

Comert, S. S., B. Caglayan, U. Akturk, A. Fidan, N. Kiral, E. Parmaksiz, B. Salepci, and B. A. Kurtulus. 2013. "The role of thoracic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism." Annals of Thoracic Medicine 8 (2):99-104. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.109822.

Costachescu, T., A. Denault, J. G. Guimond, P. Couture, S. Carignan, P. Sheridan, G. Hellou, et al. 2002. "The hemodynamically unstable patient in the intensive care unit: hemodynamic vs. transesophageal echocardiographic monitoring." Critical Care Medicine 30 (6):1214-23.

Cowie, B. 2011. "Three years' experience of focused cardiovascular ultrasound in the peri-operative period." Anaesthesia 66 (4):268-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06622.x.

Denault, A., Y. Lamarche, A. Rochon, J. Cogan, M. Liszkowski, J. S. Lebon, C. Ayoub, et al. 2014a. "Innovative approaches in the perioperative care of the cardiac surgical patient in the operating room and intensive care unit." Canadian Journal of Cardiology 30 (12 Suppl):S459-77. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.09.029.

Denault, A., A. Vegas, and C. Royse. 2014b. "Bedside clinical and ultrasound-based approaches to the management of hemodynamic instability--part I: focus on the clinical approach: continuing professional development." Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 61 (9):843-64. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0203-0.

Denault, AY, A Vegas, Y Lamarche, JC Tardif, and P Couture. 2018. Basic Transesophageal and Critical Care Ultrasound: Taylor and Francis, CRC Press.

Diaz-Gomez, J. L., H. L. Frankel, and A. Hernandez. 2017. "National Certification in Critical Care Echocardiography: Its Time Has Come." Critical Care Medicine 45 (11):1801-4. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002707.

Ducrocq, X., M. Braun, M. Debouverie, C. Junges, M. Hummer, and H. Vespignani. 1998. "Brain death and transcranial Doppler: experience in 130 cases of brain dead patients." Journal of the Neurological Sciences 160 (1):41-6.

Eljaiek, R., Y. A. Cavayas, E. Rodrigue, G. Desjardins, Y. Lamarche, F. Toupin, A.Y. Denault, and W. Beaubien-Souligny. 2018 (In press). "Pulsatile portal venous flow as a marker of the clinical impact of venous hypertension in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study." British Journal of Anesthesiology.

Ferrada, P., D. Evans, L. Wolfe, R. J. Anand, P. Vanguri, J. Mayglothling, J. Whelan, et al. 2014. "Findings of a randomized controlled trial using limited transthoracic echocardiogram (LTTE) as a hemodynamic monitoring tool in the trauma bay." J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76 (1):31-7; discussion 7-8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a74ad9.

Ford, J. W., J. Heiberg, A. P. Brennan, C. F. Royse, D. J. Canty, D. El-Ansary, and A. G. Royse. 2017. "A Pilot Assessment of 3 Point-of-Care Strategies for Diagnosis of Perioperative Lung Pathology." Anesthesia and Analgesia 124 (3):734-42. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001726.

Froudarakis, M. E. 2008. "Diagnostic work-up of pleural effusions." Respiration 75 (1):4-13. doi: 10.1159/000112221.

Guyton, A. C., A. W. Lindsey, B. Abernathy, and T. Richardson. 1957. "Venous Return at Various Right Atrial Pressures and the Normal Venous Return Curve." American Journal of Physiology 189 (3):609-15.

Haji, K., D. Haji, D. J. Canty, A. G. Royse, D. Tharmaraj, M. Azraee, L. Hopkins, and C. F. Royse. 2018. "The Feasibility and Impact of Routine Combined Limited Transthoracic Echocardiography and Lung Ultrasound on Diagnosis and Management of Patients Admitted to ICU: A Prospective Observational Study." Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 32 (1):354-60. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.08.026.

Heiberg, J., D. El-Ansary, D. J. Canty, A. G. Royse, and C. F. Royse. 2016. "Focused echocardiography: a systematic review of diagnostic and clinical decision-making in anaesthesia and critical care." Anaesthesia 71 (9):1091-100. doi: 10.1111/anae.13525.

Hulin, J., P. Aslanian, G. Desjardins, M. Belaidi, and A. Denault. 2016. "The Critical Importance of Hepatic Venous Blood Flow Doppler Assessment for Patients in Shock." A A Case Rep 6 (5):114-20. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000252.

Iida, N., Y. Seo, S. Sai, T. Machino-Ohtsuka, M. Yamamoto, T. Ishizu, Y. Kawakami, and K. Aonuma. 2016. "Clinical Implications of Intrarenal Hemodynamic Evaluation by Doppler Ultrasonography in Heart Failure." JACC Heart Fail 4 (8):674-82. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.03.016.

Jones, A. E., V. S. Tayal, D. M. Sullivan, and J. A. Kline. 2004. "Randomized, controlled trial of immediate versus delayed goal-directed ultrasound to identify the cause of nontraumatic hypotension in emergency department patients." Critical Care Medicine 32 (8):1703-8.

Joseph, M. X., P. J. Disney, R. Da Costa, and S. J. Hutchison. 2004. "Transthoracic echocardiography to identify or exclude cardiac cause of shock." Chest 126 (5):1592-7. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1592.

Kanji, H. D., J. McCallum, D. Sirounis, R. MacRedmond, R. Moss, and J. H. Boyd. 2014. "Limited echocardiography-guided therapy in subacute shock is associated with change in management and improved outcomes." Journal of Critical Care 29 (5):700-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.04.008.

Karabinis, A., M. Fragou, and D. Karakitsos. 2010. "Whole-body ultrasound in the intensive care unit: a new role for an aged technique." Journal of Critical Care 25 (3):509-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.07.001.

Kimchi, A., A. G. Ellrodt, D. S. Berman, M. S. Riedinger, H. J. Swan, and G. H. Murata. 1984. "Right ventricular performance in septic shock: a combined radionuclide and hemodynamic study." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 4 (5):945-51.

Lau, V. I., and R. T. Arntfield. 2017. "Point-of-care transcranial Doppler by intensivists." Crit Ultrasound J 9 (1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13089-017-0077-9.

Laursen, C. B., E. Sloth, A. T. Lassen, Rd Christensen, J. Lambrechtsen, P. H. Madsen, D. P. Henriksen, J. R. Davidsen, and F. Rasmussen. 2014. "Point-of-care ultrasonography in patients admitted with respiratory symptoms: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial." Lancet Respir Med 2 (8):638-46. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70135-3.

Legrand, M., B. Le Cam, S. Perbet, C. Roger, M. Darmon, P. Guerci, A. Ferry, et al. 2016. "Urine sodium concentration to predict fluid responsiveness in oliguric ICU patients: a prospective multicenter observational study." Critical Care (London, England) 20 (1):165. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1343-0.

Levitt, M. A., and B. A. Jan. 2002. "The effect of real time 2-D-echocardiography on medical decision-making in the emergency department." Journal of Emergency Medicine 22 (3):229-33.

Lichtenstein, D. A., N. Lascols, G. Meziere, and A. Gepner. 2004. "Ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill." Intensive Care Medicine 30 (2):276-81. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2075-6.

Lichtenstein, D. A., and G. A. Meziere. 2008. "Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol." Chest 134 (1):117-25. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2800.

Maissan, I. M., P. J. Dirven, I. K. Haitsma, S. E. Hoeks, D. Gommers, and R. J. Stolker. 2015. "Ultrasonographic measured optic nerve sheath diameter as an accurate and quick monitor for changes in intracranial pressure." Journal of Neurosurgery 123 (3):743-7. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS141197.

Manasia, A. R., H. M. Nagaraj, R. B. Kodali, L. B. Croft, J. M. Oropello, R. Kohli-Seth, A. B. Leibowitz, et al. 2005. "Feasibility and potential clinical utility of goal-directed transthoracic echocardiography performed by noncardiologist intensivists using a small hand-carried device (SonoHeart) in critically ill patients." Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 19 (2):155-9. doi: 10.1053//j.jvca.2005.01.023.

Marcelino, P. A., S. M. Marum, A. P. Fernandes, N. Germano, and M. G. Lopes. 2009. "Routine transthoracic echocardiography in a general Intensive Care Unit: an 18 month survey in 704 patients." European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (3):e37-42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.09.015.

Mayo, P. H., Y. Beaulieu, P. Doelken, D. Feller-Kopman, C. Harrod, A. Kaplan, J. Oropello, et al. 2009. "American College of Chest Physicians/La Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography." Chest 135 (4):1050-60. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2305.

Melniker, L. A., E. Leibner, M. G. McKenney, P. Lopez, W. M. Briggs, and C. A. Mancuso. 2006. "Randomized controlled clinical trial of point-of-care, limited ultrasonography for trauma in the emergency department: the first sonography outcomes assessment program trial." Annals of Emergency Medicine 48 (3):227-35. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.008.

Najjar, A., A. Y. Denault, and M. W. Bojanowski. 2017. "Bedside transcranial sonography monitoring in a patient with hydrocephalus post subarachnoid hemorrhage." Crit Ultrasound J 9 (1):17. doi: 10.1186/s13089-017-0072-1.

Narita, T., S. Hatakeyama, T. Koie, S. Hosogoe, T. Matsumoto, O. Soma, H. Yamamoto, et al. 2017. "Presence of transient hydronephrosis immediately after surgery has a limited influence on renal function 1 year after ileal neobladder construction." BMC Urology 17 (1):72. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0263-x.

Narula, J., Y. Chandrashekhar, and E. Braunwald. 2018. "Time to Add a Fifth Pillar to Bedside Physical Examination: Inspection, Palpation, Percussion, Auscultation, and Insonation." JAMA Cardiol 3 (4):346-50. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0001.

Nijst, P., P. Martens, M. Dupont, W. H. W. Tang, and W. Mullens. 2017. "Intrarenal Flow Alterations During Transition From Euvolemia to Intravascular Volume Expansion in Heart Failure Patients." JACC Heart Fail 5 (9):672-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.05.006.

Ninet, S., D. Schnell, A. Dewitte, F. Zeni, F. Meziani, and M. Darmon. 2015. "Doppler-based renal resistive index for prediction of renal dysfunction reversibility: A systematic review and meta-analysis." Journal of Critical Care 30 (3):629-35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.02.008.

Orme, R. M., M. P. Oram, and C. E. McKinstry. 2009. "Impact of echocardiography on patient management in the intensive care unit: an audit of district general hospital practice." British Journal of Anaesthesia 102 (3):340-4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen378.

Piette, E., R. Daoust, and A. Denault. 2013. "Basic concepts in the use of thoracic and lung ultrasound." Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 26 (1):20-30. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32835afd40.

Plummer, D., D. Brunette, R. Asinger, and E. Ruiz. 1992. "Emergency department echocardiography improves outcome in penetrating cardiac injury." Annals of Emergency Medicine 21 (6):709-12.

Prowle, J. R., J. E. Echeverri, E. V. Ligabo, C. Ronco, and R. Bellomo. 2010. "Fluid balance and acute kidney injury." Nat Rev Nephrol 6 (2):107-15. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.213.

Romero-Bermejo, F. J., M. Ruiz-Bailen, J. Gil-Cebrian, and M. J. Huertos-Ranchal. 2011. "Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy." Current Cardiology Reviews 7 (3):163-83.

Rozycki, G. S., R. B. Ballard, D. V. Feliciano, J. A. Schmidt, and S. D. Pennington. 1998. "Surgeon-performed ultrasound for the assessment of truncal injuries: lessons learned from 1540 patients." Annals of Surgery 228 (4):557-67.

Schnell, D., and M. Darmon. 2012. "Renal Doppler to assess renal perfusion in the critically ill: a reappraisal." Intensive Care Medicine 38 (11):1751-60. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2692-z.

Schnell, D., M. Reynaud, M. Venot, A. L. Le Maho, M. Dinic, M. Baulieu, G. Ducos, et al. 2014. "Resistive Index or color-Doppler semi-quantitative evaluation of renal perfusion by inexperienced physicians: results of a pilot study." Minerva Anestesiologica 80 (12):1273-81.

Silva, J. M., Jr., A. M. de Oliveira, F. A. Nogueira, P. M. Vianna, M. C. Pereira Filho, L. F. Dias, V. P. Maia, et al. 2013. "The effect of excess fluid balance on the mortality rate of surgical patients: a multicenter prospective study." Critical Care (London, England) 17 (6):R288. doi: 10.1186/cc13151.

Soldatos, T., K. Chatzimichail, M. Papathanasiou, and A. Gouliamos. 2009. "Optic nerve sonography: a new window for the non-invasive evaluation of intracranial pressure in brain injury." Emergency Medicine Journal 26 (9):630-4. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.058453.

Stanko, L. K., E. Jacobsohn, J. W. Tam, C. J. De Wet, and M. Avidan. 2005. "Transthoracic echocardiography: impact on diagnosis and management in tertiary care intensive care units." Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 33 (4):492-6.

Turner, K. L., L. J. Moore, S. R. Todd, J. F. Sucher, S. A. Jones, B. A. McKinley, A. Valdivia, R. M. Sailors, and F. A. Moore. 2011. "Identification of cardiac dysfunction in sepsis with B-type natriuretic peptide." Journal of the American College of Surgeons 213 (1):139-46; discussion 46-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.03.027.

Vallabhajosyula, S., M. Kumar, G. Pandompatam, A. Sakhuja, R. Kashyap, K. Kashani, O. Gajic, J. B. Geske, and J. C. Jentzer. 2017. "Prognostic impact of isolated right ventricular dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock: an 8-year historical cohort study." Ann Intensive Care 7 (1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0319-9.

Vegas, A., A. Denault, and C. Royse. 2014. "A bedside clinical and ultrasound-based approach to hemodynamic instability - Part II: bedside ultrasound in hemodynamic shock: continuing professional development." Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 61 (11):1008-27. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0231-9.

Volpicelli, G., V. Caramello, L. Cardinale, and M. Cravino. 2008. "Diagnosis of radio-occult pulmonary conditions by real-time chest ultrasonography in patients with pleuritic pain." Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology 34 (11):1717-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.04.006.

Xirouchaki, N., E. Kondili, G. Prinianakis, P. Malliotakis, and D. Georgopoulos. 2014. "Impact of lung ultrasound on clinical decision making in critically ill patients." Intensive Care Medicine 40 (1):57-65. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3133-3.

Yang, Y., C. Royse, A. Royse, K. Williams, and D. Canty. 2016. "Survey of the training and use of echocardiography and lung ultrasound in Australasian intensive care units." Critical Care (London, England) 20 (1):339. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1444-9.

Yumoto, T., Y. Kondo, K. Kumon, Y. Masaoka, T. Hiraki, T. Yamada, H. Naito, and A. Nakao. 2018. "Delayed hydronephrosis due to retroperitoneal hematoma after a seatbelt injury: A case report." Medicine (Baltimore) 97 (23):e11022. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000011022.

Zanobetti, M., C. Poggioni, and R. Pini. 2011. "Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED?" Chest 139 (5):1140-7.

Zanobetti, M., M. Scorpiniti, C. Gigli, P. Nazerian, S. Vanni, F. Innocenti, V. T. Stefanone, et al. 2017. "Point-of-Care Ultrasonography for Evaluation of Acute Dyspnea in the ED." Chest 151 (6):1295-301. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.003.

Zhang, M., Z. H. Liu, J. X. Yang, J. X. Gan, S. W. Xu, X. D. You, and G. Y. Jiang. 2006. "Rapid detection of pneumothorax by ultrasonography in patients with multiple trauma." Critical Care (London, England) 10 (4):R112. doi: 10.1186/cc5004.