ICU Management & Practice, Volume 16 - Issue 3, 2016

We argue that a jumble of rules, protocols, checklists has emerged, which jeopardises not only the pivotal relationship between doctor and patient, but also the quality and costs of care, and the quality of future healthcare workers. It must be emphasised that the introduction of protocols and checklists in clinical medicine has improved care at some points and in some places, and it has similarly contributed to a reduction in errors. However, the onerous bureaucratic rules, regulations, protocols, certifications and credentialing imposed by administrators and “oversight” organisations have become disproportionate to its original objectives. We plead that clinicians realise that the time has come to rebel against this and come into action.

Caring for the sick and dying is a privilege that society has bestowed upon physicians. Patients and their families trust physicians with their lives and health. Physicians spend years in training and ongoing professional development with the goal of providing the highest quality of care with compassion and humility. However, the culture of modern medicine has rapidly eroded the unique and time-honoured relationship the physician has with his/her patients.

Increasingly, hospital administrators, insurance providers, quality organisations and a myriad of regulatory agencies are dictating how physicians should practise medicine. Unfortunately, too many of the individuals creating and enforcing these regulations have little or no knowledge of the complexity of the practice of medicine. They regard physicians as labourers working in a widget factory. Consequently, physicians have lost autonomy and the sacred patient-physician relationship has been corroded. In this new environment, the dehumanisation of the patient-physician relationship is at risk of being exacerbated by the new generation of healthcare providers, trained in this—in our view—undesirable environment. This new generation of clinicians is at risk of being brought up lacking the concept of hard work and dedication, “patient ownership” and responsibility.

With the exponential growth of medical knowledge and technology, clinicians are continuously being challenged by complex new diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Simultaneously the organisation of patient care is changing with an ever-increasing number of organisations and non-medical individuals involved in the delivery of healthcare. Society demands, and rightly so, accountability regarding the quantitative, qualitative and financial aspects of patient care. In response to these demands, hospital managers and administrators, individuals with little or no knowledge of medicine, have become increasingly involved in almost all aspects of the delivery of care. In order to have—apparent—total control over the entire patient experience, these managers demand the use of numbers and measurements as a reflection of the quality of care delivered. An additional factor that is emerging in Europe, which has followed the movement in the United States, is the regulatory demand that all possible adverse outcomes be outlawed. At first sight this would seem reasonable; however, medicine is not a perfect science and sick patients will develop complications no matter how hard one tries to avoid them. The sicker and more complex the patient the greater the likelihood that a complication will occur. The institution of punitive measures (financial, otherwise or in terms of reputation damage) in response to a bad outcome will frequently lead to changes in behaviour which may compromise patient care, e.g. not doing blood cultures in a case of suspected catheter-related bloodstream infection to prevent the diagnosis being made.

Another misunderstanding is the belief that there is only one truth. Diversity in medicine, patients and diseases is so big that it seems inconceivable that one solution for complex syndromes like sepsis, with many possible underlying diseases, in the form of a protocol and checklists, is advocated. Yet what we see, with the intention to rule out all possible risks and errors, is an increasing number of rules, legislation and protocols. Oddly enough, professional medical societies have not protested against this movement; on the contrary, they have frequently endorsed and perpetuated this approach. The result is a jungle of rules and protocols from medical and scientific societies, governmental and other non-medical bodies such as insurance companies. Physicians and clinical leaders are confronted with more and more requirements, rules, audits, inspections, compliance training and protocols, imposed by governmental and non-governmental organisations, insurance companies, accreditation organisations, inspectorates and boards of directors of hospitals. With all the regulatory administrative tasks that physicians are forced to undertake, it is not rocket science to realise that less and less time remains available for the primary process: patient care. Apart from impacting patient care, the time wasted jeopardises clinical research, education and the training of students and registrars. Additionally, research and training are hampered by an increasing number of rules, regulations and mandatory non-functional courses. Many of these mandatory courses are not only meant for the teachers, but also for their PhD students. The distance between workers on the shop floor, the healthcare workers, and on the other hand those people who make the regulations is growing and they speak different languages. All kinds of bodies and committees in hospitals offer training programmes, the additional value of which is questionable in terms of patient outcome or educational quality. It might come to one’s mind that these bodies are mainly preoccupied with providing new work for themselves, creating rules, work and training programmes of unclear benefit.

See Also: Medical Documentation: Fair Return on Time Investment?

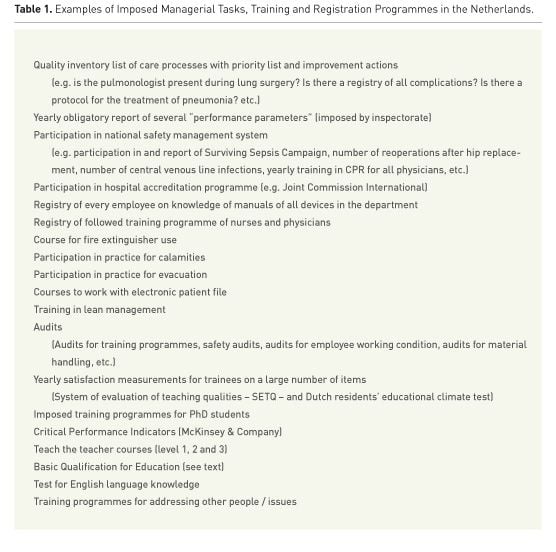

A simple recent survey that the

first author (AG) conducted among some board directors of hospitals,

demonstrated that they have insufficient insight into the huge number of

obligations imposed by different bodies on medical specialists and nurses. Table

1 provides an incomplete but illustrative overview of the Dutch situation.

The quality movement has imposed

the increased use of protocols and checklists with the intention to improve

quality of care. This is accompanied by obligatory ticking off and securing of

lists that go through implicit procedures. While protocols were initially

intended to provide up-todate medical knowledge translated into clinically and

practically applicable information, currently all kinds of procedures need to

be embodied in protocols, which need to be secured by checklists and repeated

evaluation according to a plan-docheck- act cycle. Subsequently, compliance to

the protocol is used as a marker of quality. Undeniably this approach has

induced improvement on certain fronts (Girbes et al. 2015; 2016). But it is

now getting out of control. Moreover, a trend can be observed that for every

rare incident a new protocol is created, without taking into account how a new

protocol might induce new errors. For example, in addition to double checking

the preparation of a medicine by an intensive care nurse, a new additional

obligatory protocol was introduced (in the Netherlands) without any evidence

or calculation of the consequence. This protocol requires that immediately

after the double check of the medication an additional double check is

required at the time of administration of the medicine. This of course

requires another ICU nurse to abandon their current activity, move to another

patient, check what is given, and then go back to continue the interrupted

work. It is beyond doubt that frequent interruption of work will induce other

errors (Westbrook et al. 2010). Of course continuous double checking would be

a dream scenario, if feasible in terms of human factors. This would however

require double the number of nurses: one nurse to do the work and another to

check the work. Considering the pressure on and shortage of human resources,

one wonders whether this is the most effective way to save lives. Furthermore,

one of the nurses would surely become bored, which is not conducive to good

concentration on doing the best work they can.

By no means do we want to argue

that errors, mistakes and undesirable outcomes should not be investigated to

recognise the “holes” in the system. However, the solution is not always the introduction

of a new protocol or checklist.

We strongly believe that the policy of

increasing the number of protocols and checklists should be reversed if we

want to keep good medical care affordable. An issue that is easily forgotten is

that we must be able to keep and attract young talented people. Increasing

rigidity of the system is, to say the least, not an incentive to motivate young

talents to work in medicine. We argue that protocols and checklists are

comparable to medicines: it is the dose that makes poison and the indication

always remains pivotal. The dose has now reached the level of poison and the indication

is too often wrong.

Jumble of Protocols and Checklists

The purpose of clinical protocols is to translate the best possible up-to-date medical knowledge into practical, clinically applicable instructions. Several studies have shown an improvement in patient outcome with the introduction of a protocol or checklist. Whether a protocol or checklist will introduce an improvement in care largely depends on how good or bad the situation was before the introduction of the protocol. Introduction of a protocol is therefore especially useful in situations of suboptimal circumstances or where inexperienced or less trained healthcare workers are employed. Furthermore, checklists are not universal. Checklists need to be intrinsically supported by staff, based on the local applicability of the checklist and support from the leadership.

Protocols will by definition lead to regression to the mean and mediocrity. Rigid application of protocols will hamper progress and innovation, and protocols are by definition not up-to-date. Finally, many protocols are made on the basis of insufficient scientific data, insufficiently possible external validation of studies or even only on the basis of the judgement of self-proclaimed “experts”. Unfortunately, healthcare managers, “organisations for quality”, supervisory bodies and healthcare insurance companies mandatorily impose the introduction of protocols and checklists for all kinds of aspects of care. The forced introduction on a national level of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in the United States and in the Netherlands, apart from many other examples, is a tragic example of this. There is insufficient scientific evidence to impose per protocol treatment according to the surviving sepsis guideline in all hospitals and even evidence that it might be harmful (Marik 2016a).

The introduction of protocols with doubtful benefit may lead to waste of time, work and money. The obligatory introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) from the ICU, implementation of all components of the time-out procedure in the operating room, reporting standard screening of feeding condition in the elderly, and scoring of community-acquired pneumonia, are examples of so-called safety programmes that cost a lot of time and money, but are of doubtful benefit for society and individual patients.

Filling in all kinds of lists is

promoted by the introduction of electronic patient record programmes. These

have been designed for administrative and financial reasons and not, as one

would expect, to improve patient care and help healthcare workers to do their

work correctly. It is no surprise that the introduction of such electronic

health records has been shown to increase the risk of professional burnout in physicians

(Shanafelt et al. 2016).

Treating individual patients optimally will always

require aspects of craftsmanship with an academic attitude and thereby

individualised treatment. Translating the use of protocols and checklists to

another craft, food preparation, might clarify some aspects. Application of protocols

only works very well in the fast-food industry. In “restaurants” where no chef

is needed the employees are easier to handle by the management of the

“restaurant” and can be paid less. Food will always be according to the guidelines

and protocols and checklists, but in the end will not fit everybody. Likewise,

even if written by a great chef, reading and following the instructions of a

cookery book will not match the quality and craft of a real chef. Proponents

of the unrestrained use of protocols and checklists often point to the analogy

and similarities between aviation and building construction. We reject that

comparison. Patients are not airplanes and doctors are not pilots. Pilots

receive very specific training in general for a single type of airplane. Since

every patient is different, it would pose serious problems if doctors were

trained like pilots.

Jumble of the Quality Movement

There should be no doubt that doctors and nurses should be accountable to patients and those who pay for them: society. And society is all of us. The healthcare payer has the right to know how their money is spent and where to find quality for the money. However, this is quite difficult to measure and instruments to measure quality are readily available. Nevertheless the “Quality Movement” has triggered a “quality tsunami” where multiple organisations have now become preoccupied with developing quality tools, quality indicators and measuring the “quality of outcomes.” These quality indicators and scorecards are frequently publicly reported and may influence reimbursement. The scientific validity of most of these quality indicators is highly questionable. It would appear that those who expend the most resources measuring quality provide the worst care (Thomson et al. 2013). The refuge that seems to be chosen now by the administrators and managers can best be described as: “If you can’t measure what is important, you make important what you measure”. So orthopaedic surgeons obligatorily record and report on the rate of reoperations for hip fractures. This of course will result in a figure, but this figure is of course full of confounders and biases (e.g. region, population characteristics, referral pattern, etc.) and nobody can tell what the figure means. A rapid survey among chairmen of university departments of orthopaedics in the Netherlands confirmed this. Nevertheless, whenever criticism is expressed about this obligation the answer is: “It is simply an obligation” or “everybody complies with it”.

Registrations furthermore do not

take into account the pollution of data that is not expressed in the data.

Subjective data are reduced to figures in a spreadsheet, suggesting that

different figures and outcomes can be compared. This becomes most hilarious

when comparing opinions. For example, during regularly performed so-called employee

satisfaction measurements we add the opinions of ambitious, looking for

security, lazy, adventurer, genius, hypochondriac, disappointed (in private

life or their career) people, divide this by the number of participants and

then we conclude that the satisfaction is 7.3! (We do not take into account

the number of employees who for several reasons do not wish to participate). The

manager will surely advocate a leadership programme to fulfil the goal for

next year: 7.8.

In the U.S. Medicare has embarked on hundreds of “quality

initiatives”, and records over 1000 “quality measures” with the purported goal

of improving the “quality of care” (Casalino et al. 2016). It has been

reported that physicians and their staff spend 15.1 hours per physician per

week dealing with external quality measures at an annual cost of over $40, 000

per physician. There is scarce data that these quality measures improve

patient outcomes. In 2006 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

developed the “Surgical Care Improvement Project” (SCIP), which became

federally mandated and linked to pay for performance in 2007 (Joint Commission

2015). SCIP incorporated a number of measures, including glycaemic control and

strict timing of prophylactic antibiotics that were required to be performed

in every patient undergoing elective surgery. In January 2015 the SCIP

project was quietly “retired” (Joint Commission 2015), after it became clear that

this very expensive and time-consuming endeavour did not improve patient

outcomes (Hawn et al. 2011; Dua et al. 2014; McDonnell et al. 2013). In 2015

CMS adopted the “SEP-1 Early Management Bundle for Severe Sepsis and Septic

Shock” for the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Programme. Most

alarmingly, it is likely that this “quality” programme” will harm patients

(Marik and Varon 2016). In the U.S. and progressively in the Netherlands,

physician’s medical records are scrutinised by individuals with limited

educational training to ensure that all elements of the history and physical examination

are documented, no matter how irrelevant. Rather than being a tool to communicate

medical information, the medical record is used as a quality indicator and a

means to punish physicians for incomplete documentation. And again a new

industry is filling this created gap: a “quality company”. Their slogan is: “Let

me measure if you have a quality issue, all your colleagues did it already.

Indeed you have a problem and we know people who can solve it”.

Jumble of Obligatory Training

Fortunately, the time of “see one, do one, teach one” is over. Many skills can be learned and improved with good training programmes and simulation sessions. This includes not only hard skills and knowledge but also so-called “soft” skills such as advanced life support in a team, team performance, bringing bad news to families and patients, and calling someone to account. Complex tasks with a low incidence cannot be dealt with in a training programme. Intentional publication fraud cannot be prevented with a course on ethics in science and neither will a course, obligatory in the Netherlands, with a duration of more than one week on regulations and organisation of clinical research prevent that. However, these rules mean that professors with many publications in leading journals, and with a research desk to guarantee all responsibilities and compliance with regulations, fail an exam because they do not know by heart how many years all records need to be stocked. The goal of good clinical practice and research, will also be missed whenever those who conduct the courses get too much influence on making it an obligation to follow these courses. This again will result in a “course industry” both within and outside the hospital, whose sole purpose is that of self-preservation. In the Netherlands, PhD students in medicine have been guided and supported for decades by established researchers and professors during their PhD study. The study outline and the interpretation of data were discussed almost on a daily basis. They participated in international congresses and presented their data during national and international meetings. However, all of a sudden specific time-consuming courses have been made obligatory for PhD students with no data to support impact on student outcome. Another remarkable obligatory regulation without any supporting data was the introduction of the Basic Qualification for Education (BQE). This training programme consists of 5 full days training, 165 hours of study, 90 hours of which are with the help of an assigned mentor. Someone with more than 30 years of educational experience, educational diplomas outside the field of medicine, who has students who value the courses and applaud during presentations and over 260 international presentations is called to follow this obligatory BQE training programme.

A long list can be generated of time-consuming training programmes with concomitant registration obligation, which can be related to demands by health insurance companies, legal authorities and accreditation programmes. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the benefit-time ratios of these programmes, but in general we would challenge those who make these regulations to demonstrate their benefit.

The question remains of how to make progress in medicine and how to prevent errors and wrong treatment. We think the key is good training programmes and a culture where healthcare workers continuously give feedback to each other. Medicine has to stay attractive for young people with an academic mindset that is challenged by all the complex problems encountered in healthcare. Whatever protocol or checklist, it should be used as a mental support for highly educated professionals and never get the force of law.

Conflict of interest

Armand Girbes declares that he has no conflict of interest. Jan Zijlstra declares that he has no conflict of interest. Paul Marik declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References:

Casalino LP, Gans D, Weber R et al. (2016) US physicians’ practices spend more than $15.4 billion annually to report quality measures. Health Aff (Millwood), 35(3): 401-6.

PubMed ↗

Dua A, Desai SS, Seabrook GR et al. (2014) The effect of Surgical Care Improvement project measures on national trends on surgical site infections in open vascular procedures. J Vasc Surg, 60(6): 1635-9.

PubMed ↗

Girbes AR, Robert R, Marik PE (2015) Protocols: help for improvement but beware of regression to the mean and mediocrity. Intensive Care Med, 41(12): 2218-20.

PubMed ↗

Girbes AR, Robert R, Marik PE (2016) The dose makes the poison. Intensive Care Med, 42(4): 632. PubMed ↗

Hawn MT, Vick CC, Richman J et al. (2011) Surgical site infection prevention: time to move beyond the surgical care improvement program. Ann Surg, 254(3): 494-9.

PubMed ↗

Joint Commission (2015) Surgical care Improvement Project (SCIP) [Accessed: 23 August 2016] Available from jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project

Marik PE (2016a) Fluid responsiveness and the six guiding principles of fluid resuscitation. Crit Care Med, Nov 13.

PubMed ↗

Marik PE, Varon J (2016) Precision medicine and the Federal sepsis initiative! Crit Care Shock, 19: 1-3. Article ↗

Marik PE(2016b) Tight glycemic control in acutely ill patients: low evidence of benefit, high evidence of harm! Intensive Care Med, 42(9): 1475-7.

PubMed ↗

McDonnell ME, Alexanian SM, Junquiera A et al. (2013) Relevance of the Surgical Care Improvement Project on glycemic control in patients undergoing cardiac surgery who receive continuous insulin infusions. J Thorac Cardiavasc Surg, 145(2): 590-4.

PubMed ↗

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C et al. (2016) Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc, 91(7): 836-48.

PubMed ↗

Thomson S, Osborn R, Squires D, Jun M. International profiles of health care systems, 2013: Australia, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the United States. New York: Commonwealth Fund. [Accessed: 23 August 2016] Available fromcommonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2013/Nov/International-Profiles-of-Health-Care-Systems.aspx

Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI et al. (2010) Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med, 170(8): 683-90.

PubMed ↗