ICU Management & Practice, Volume 16 - Issue 3, 2016

The enteral route is commonly accepted as the first choice for providing nutrition to patients in the ICU with stable haemodynamics and a functional gastrointestinal (GI) tract. However, there is wide uncertainty regarding safe enteral nutrition in patients with critical pathology in the abdomen. In the current review we address different abdominal conditions in critically ill patients where safety and feasibility of enteral nutrition might be questioned. We discuss respective pathophysiological mechanisms, existing evidence and practical aspects.

Enteral nutrition (EN) prevents loss of physical and immunological barrier function (Kudsk 2002; McClave 2009). Early EN reduces infections and is recommended in critically ill patients with stable haemodynamics and functional gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Taylor et al. 2016).

Feeding in the Early Phase of Critical Illness

Even if feeding is started early, a negative energy balance in the first acute phase of critical illness is generally unavoidable. New insights show that early hypocaloric nutrition may even be preferred (Casaer and Van den Berghe 2014) because of an inflammation-induced endogenous energy production and nutrition-induced inhibition of autophagy. Therefore early EN should be started at a low rate in the acute phase and be slowly increased towards target. This is especially true in patients with, or after, abdominal crisis, with continuing vulnerability of GI tract.

Based on common sense, EN is considered harmful in the case of the clinical syndrome called “acute abdomen”, in case of obvious gut ischaemia, mechanical obstruction or perforation, and in cases with no continuity of GI tract. In most other abdominal pathologies initiation of EN remains a matter of “try and see”, e.g. starting low dose EN and evaluating feeding tolerance/intolerance.

Feeding intolerance (FI) is not uniformly defined; gastric residual volumes (GRV) have been mainly used for assessment of FI (Reintam Blaser et al. 2014). Some authors suggest abandoning GRV measurements all together (Reignier et al. 2013). We suggest that GRVs may still be useful to avoid gastric overfilling in the initial phase of EN or in the presence of abdominal symptoms (e.g. abdominal distension or pain). Evaluation of gastric filling with ultrasound may offer a good alternative to GRV (Gilja et al. 1999).

Enteral Nutrition in Specific Abdominal Conditions

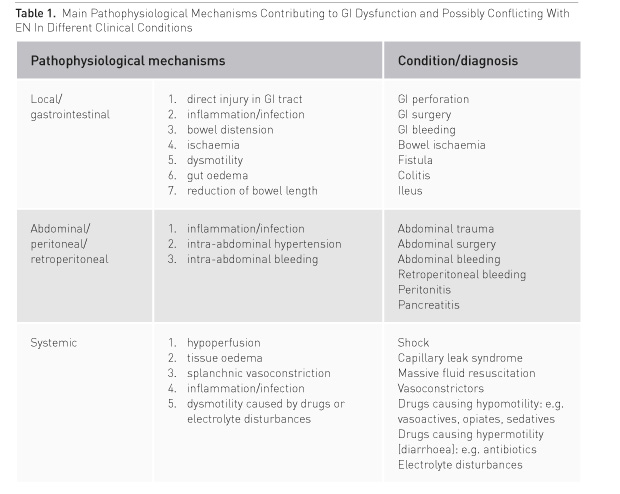

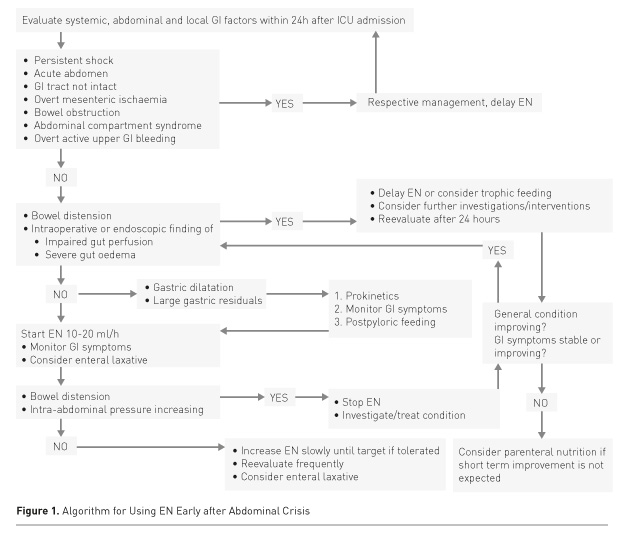

In critically ill patients with severe abdominal pathology, both abdominal pathology and systemic disease may contribute to GI dysfunction (Table 1). GI function will usually recover if haemodynamics and gut perfusion improve, fluid resuscitation-induced gut oedema resolves and analgo-sedation can be reduced. On the contrary, a patient with persisting severe general condition is prone to complications. Thus EN should be initiated at a low rate and slowly increased under careful monitoring of abdominal symptoms to avoid dilatation of the stomach, bowel distension and increasing intraabdominal pressure (IAP) (Figure 1).

Emergency Gastrointestinal Surgery

Direct injury of the GI tract due to trauma or surgery and/or infection/inflammation leads to gut oedema and dysmotility. Denervation, discontinuation of spinal reflexes and resection of enterochromaffin cells producing motilin may add to gut paresis. In emergency GI surgery, gut hypoperfusion due to shock, bowel oedema and intra-abdominal hypertension, exacerbated by inflammation and massive fluid resuscitation, is often evident. Therefore, major factors to consider for recovery after emergency GI surgery (if bowel continuity is restored) are: bowel perfusion, bowel oedema and bowel distension. The intraoperative evaluation of bowel viability is important; therefore good communication with surgeons is crucial. If a stoma is created and bowel cranial to stoma has normal appearance, low dose EN can usually be started within 24 hours. In elective surgery, performed anastomoses will likely heal better with EN than without (Boelens et al. 2014). The risk of anastomotic leak is much higher if an anastomosis is performed during emergency surgery, but there is no evidence on harmfulness of early EN in this situation. A positive effect of early EN regarding infections after emergent GI surgery has been shown in one randomised controlled study (Singh et al. 1998).

Damage control surgery enables postponement of restoration of bowel continuity until hypoperfusion, oedema and distension are resolved. Still, trophic EN might already be considered if a diverting stoma is present and the next surgery is not planned within the next 24 hours.

In patients with prolonged abdominal sepsis requiring multiple interventions and clearly not reaching their energy and protein targets with EN, supplemental PN should be considered after a couple of days, while avoiding overfeeding. Supplemental PN should also be considered if such patients have severe diarrhoea with impaired absorption of nutrients.

Open Abdomen

Patients with open abdomen often require multiple surgeries and have increased risk for fistula formation. A few studies have shown that EN is feasible in patients with open abdomen and is associated with a higher rate of abdominal closure and a lower incidence of ventilatorassociated pneumonia (Collier 2007; Byrnes et al. 2010; Dissanaike 2008).

EN should be applied early, as soon as bowel continuity is confirmed or restored and haemodynamic and tissue perfusion goals can be reached with or without vasopressors/ inotropes. Continuing need for fluid resuscitation may refer to unsolved abdominal pathology, whereas losses due to the open abdomen need to be taken into account.

See Also: What’s the Benefit of Enteral Nutrition? Updated Review

Abdominal Aortic

Surgery

Rupture of the abdominal aorta and associated surgery carry a risk of massive bleeding and transfusion, retroperitoneal haematoma formation and impaired gut perfusion, which might be an argument for delaying EN in these patients. The major adverse event after abdominal aortic surgery is colonic ischaemia (CI), which occurs in about 2% of patients after elective surgery for aneurysm, and 10% in case of rupture (Björck et al. 1996; Van Damme et al. 2000), somewhat less in endovascular repair (Becquemin et al. 2008). Presumed causes of CI are ligation or obstruction of supply arteries (inferior mesenteric artery, hypogastric arteries, meandering mesenteric arteries), non-occlusive ischaemia due to shock or vasopressor drugs, and (micro) embolisation (Steele 2007).

Length of operation, aneurysm rupture and renal insufficiency are independent risk factors of CI (Becquemin et al. 2008). Surgical details (reimplantation of inferior mesenteric artery, intraoperative assessment of blood flow by Doppler flowmetry, large bowel viability, etc.) should be carefully recognised. The main clinical symptoms of CI are early diarrhoea, haematoschisis (Björck et al. 1996) and ileus (Valentine et al. 1998). Colonoscopy remains the method of choice to detect ischaemic lesions of colonic mucosa, but its routine application is not supported (Steele 2007). Whether and how the endoscopic findings can guide EN is not clear. Circulating biochemical markers such as intestinal fatty acid-binding protein may facilitate the recognition of CI (Vermeulen Windsant et al. 2012), but whether this information can be used for feeding decisions remains unknown.

Taking the relatively low incidence of CI, it is not rational to delay EN in all patients routinely for several days after abdominal aortic surgery. Instead, EN should be initiated with low dose under careful monitoring of abdominal symptoms, IAP and signs of CI, and increased gradually (van Zanten 2013). In overt bowel ischaemia, EN should be withheld.

Abdominal Trauma

Abdominal trauma is a complex injury, where a multidisciplinary approach has made non-operative management increasingly feasible and effective (Prachalias and Kontis 2014). Early EN may be well integrated in this approach. However, obstacles such as GI tract discontinuity, compromised gut perfusion and/or abdominal compartment syndrome may necessitate delay of EN. At the same time, some older RCTs using needle catheter jejunostomy have shown benefit of early EN over early PN (Kudsk 1992) and over delayed EN (Moore 1986) regarding infectious complications. We suggest starting EN early after abdominal trauma if continuity of GI tract is confirmed/restored, and abdominal compartment syndrome and bowel ischaemia excluded.

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS), defined as IAP above 20 mmHg along with new or worsening organ failure, is an immediately life-threatening condition, where prompt measures to reduce IAP are needed. These measures include decompression of GI tract and avoidance of adding any volume into the abdomen (Kirkpatrick et al. 2013), thereby excluding EN. Moreover, splanchnic perfusion is severely jeopardised during ACS.

EN should be considered at elevated IAPs between 12 and 20 mmHg without ACS, but high incidence of feeding intolerance has been described (Reintam et al 2008). Further, EN itself may cause an increase in IAP. We suggest incorporating IAP measurements into standard monitoring of critically ill patients with abdominal pathologies in the initial phase of EN, and cessation of feeding to be considered if worsening of clinical status is possibly attributed to increasing IAP.

Severe GI Bleeding

Patients admitted to the ICU due to acute GI bleeding require immediate diagnostics and intervention to localise and stop bleeding. EN might be considered when the bleeding has been stopped endoscopically or surgically. The main rationale to withhold EN after stopping active bleeding is disturbed visibility if a new endoscopy is needed; therefore delaying enteral intake for at least 48 hours in case of high risk of rebleeding has been suggested (Hébuterne and Vanbiervliet 2011). Such a time frame is not well justified nor supported by the evidence. We suggest that when upper GI bleeding has been stopped and there are no signs of rebleeding, low dose EN can be started within 48 hours. In case of lower GI bleeding EN could be started immediately.

Bowel Ischaemia

EN increases gut perfusion (Matheson 2000), but only if the vasculature is intact and the systemic haemodynamics sufficient. There is broad consensus to withhold EN in patients with suspected small bowel ischaemia. This condition requires optimisation of the circulation and, if symptoms of ischaemia persist, a surgical or radiological intervention. In addition, continuous thoracic epidural anaesthesia may increase splanchnic blood flow by blocking afferent sympathic reflexes (Holte 2000). Local mucosal ischaemia of the colon has a tendency to heal when the general condition of the patient improves. Therefore EN should be considered in patients with colonic mucosal ischaemia without bowel distension. Bowel distension may possibly be aggravated by EN and lead to further impairment of bowel wall perfusion. We suggest that EN should not be started if transmural bowel ischaemia is confirmed or suspected or signs of local mucosal ischaemia are seen in severely distended bowel.

Bowel Obstruction

Bowel obstruction leads to obstructive ileus, with initial hypermotility (be warned: presence of bowel sounds is misleading) to force bowel contents through the obstruction and subsequent bowel distension above the obstruction. Bowel obstruction requires a surgical or endoscopic intervention to restore passage of bowel contents or to create a proximal stoma. EN should be withheld in case of obstructive symptoms, but can be carefully initiated as soon as passage is restored or a proximal stoma has been created. It may take a couple of days before bowel distension and paresis are resolved and EN can be increased.

Bowel Paralysis

EN itself promotes motility and has beneficial effects regarding the physical and immunological gut barrier, whereas prolonged enteral fasting will aggravate dysmotility and should be avoided. Since gastroparesis is often more pronounced than small intestinal paralysis, the use of prokinetics and postpyloric feeding should be considered early in case of gastric intolerance to EN. However, paralytic ileus is often encountered in patients with peritonitis. Inflammation-induced dysmotility is mediated by cytokines and nitric oxide produced by locally activated macrophages in the muscular layer, and by neuronal pathways (Schmidt et al. 2012). Non-abdominal sepsis may also be associated with bowel paresis, due to the release of nitric oxide, which causes bowel relaxation, oxidative stress and the systemic release of tumour necrosis factor (TNF), which inhibits the central vagal pathways (Emch et al. 2000). Furthermore, many conditions and therapies in critically ill patients (e.g. hyperglycaemia, hypokalaemia, acidosis, use of dopamine, opioids, clonidine and dexmedetomidine) may contribute to bowel paralysis.

In rare cases, isolated large bowel distension mainly in the caecum region occurs called Ogilvie’s syndrome seu colonic pseudoobstruction. This condition carries high risk of bowel ischaemia and perforation due to distension, and should be promptly recognised and managed (Oudemans-van Straaten 2011; De Giorgio and Knowles 2009) with intravenous neostigmine (van der Spoel et al. 2001; Valle and Godoy 2014), endoscopic decompression or temporary coecostomy. Early start of lactulose or polyethylene glycol (van der Spoel et al. 2007) and neostigmine, if defaecation does not occur, may help to prevent Ogilvie’s syndrome. In less severe cases of bowel paralysis, there are no confirmed contraindications to start a trial of low dose EN under careful monitoring of symptoms and promotion of defaecation with laxatives and neostigmine.

Acute Colitis with Toxic Megacolon

Acute colitis as a cause of diarrhoea in intensive care is a rare condition that is mostly caused by a Clostridium difficile infection. Sometimes severe enterocolitis is caused by chemotherapy for haematological disorders. In most severe cases toxic megacolon—a severe and life-threatening condition associated with systemic toxicity— may develop (Oudemans-van Straaten 2011). Colitis requires specific therapy, including antibiotics, discontinuation of motility impairing drugs, replacement of intravenous fluids, electrolytes, trace elements and vitamins (Dickinson 2014; Oudemans-van Straaten 2011). In rare cases of toxic megacolon, total colectomy becomes necessary for the patient’s survival. In most patients with colitis, there is no contraindication for EN, because the small intestine is intact. However, EN should probably not be applied to patients with toxic megacolon.

Conclusions

In most patients EN should be considered early after initial management of abdominal crisis, when continuity of GI tract is confirmed or restored, and bowel ischaemia and abdominal compartment syndrome are excluded. However, EN should be started at a slow rate under careful monitoring of GI symptoms and IAP.

Conflict of interest

Annika Reintam Blaser declares that she has no conflict of interest. Heleen M. Oudemans-van Straaten declares that she has no conflict of interest. Joel Starkopf declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ACS abdominal compartment syndrome

CI colonic ischaemia

EN enteral nutrition

FI feeding intolerance

GRV gastric residual volume

IAP intra-abdominal pressure

TNF tumour necrosis factor

References:

Becquemin JP, Majewski M, Fermani N et al. (2008) Colon ischemia following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the era of endovascular abdominal aortic repair. J Vasc Surg, 47(2): 258-63.

Björck M, Bergqvist D, Troëng T (1996) Incidence and clinical presentation of bowel ischaemia after aortoiliac surgery - 2930 operations from a population-based registry in Sweden. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 12(2): 139-44.

PubMed ↗

Boelens PG, Heesakkers FF, Luyer MD et al. (2014) Reduction of postoperative ileus by early enteral nutrition in patients undergoing major rectal surgery: prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg, 259(4): 649-55.

PubMed ↗

Byrnes MC, Reicks P, Irwin E (2010) Early enteral nutrition can be successfully implemented in trauma patients with an "open abdomen". Am J Surg, 199(3): 359-62.

PubMed ↗

Casaer MP, Van den Berghe G (2014) Nutrition in the acute phase of critical illness. N Engl J Med, 370(13): 1227-36.

PubMed ↗

Collier B, Guillamondegui O, Cotton B et al. (2007) Feeding the open abdomen. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 31(5): 410-5.

PubMed ↗

De Giorgio R, Knowles CH (2009) Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Br J Surg, 96(3): 229-39.

PubMed ↗

Dickinson B, Surawicz C (2014) Infectious diarrhea: an overview. Curr Gastroenterol Rep, 16(8): 399.

PubMed ↗

Dissanaike S, Pham T, Shalhub S et al. (2008) Effect of immediate enteral feeding on trauma patients with an open abdomen: protection from nosocomial infections. J Am Coll Surg, 207(5): 690-7.

PubMed ↗

Emch GS, Hermann GE, Rogers RC (2000) TNF-alpha activates solitary nucleus neurons responsive to gastric distension. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 279(3): 582-6.

PubMed ↗

Gilja OH, Hausken T, Odegaard S et al. (1999) Gastric emptying measured by ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol, 5(2): 93-4.

PubMed ↗

Hébuterne X, Vanbiervliet G (2011) Feeding the patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 14(2): 197-201.

PubMed ↗

Holte K, Kehlet H (2000) Postoperative ileus: a preventable event. Br J Surg, 87(11): 1480-93.

PubMed ↗

Kirkpatrick AV, Roberts DJ, De Waele J et al. (2013) Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med, 39(7): 1190-206.

PubMed ↗

Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Fabian TC et al. (1992) Enteral versus parenteral feeding. Effects on septic morbidity after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Ann Surg: 215(5): 503-11.

PubMed ↗

Kudsk KA (2002) Current aspects of mucosal immunity and its influence by nutrition. Am J Surg, 183(4): 390-8.

PubMed ↗

Matheson PJ, Wilson MA, Garrison RN (2000) Regulation of intestinal blood flow. J Surg Res, 93: 182–96. PubMed ↗

McClave SA, Heyland DK (2009) The physiological response and associated clinical benefits from provision of early enteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract, 24(3): 305-15.

PubMed ↗

Moore EE, Jones TN (1986) Benefits of immediate jejunostomy feeding after major abdominal trauma - a prospective, randomized study. J Trauma, 26(10): 874-81.

PubMed ↗

Oudemans-van Straaten HM (2011) Acute megacolon in the critically ill. In: Vincent JL, Abraham E, Kochanek P et al. eds. Textbook of Critical Care, 6th ed. , Philadelphia: Elsevier, Ch 107. [Accessed: 4 August 2016] Available from eu.elsevierhealth.com/textbook-of-critical-care-9781437713671.html?dmnum=12449

Prachalias AA, Kontis E (2014) Isolated abdominal trauma: diagnosis and clinical management considerations. Curr Opin Crit Care, 20(2): 218-25.

PubMed ↗

Reignier J, Mercier E, Le Gouge A et al. (2013) Effect of not monitoring residual gastric volume on risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults receiving mechanical ventilation and early enteral feeding: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 309(3): 249-56.

PubMed ↗

Reintam A, Parm P, Kitus R et al. (2008) Gastrointestinal Failure score in critically ill patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care, 12: R90. Erratum in Crit Care, 12(6): 435.

PubMed ↗

Reintam Blaser AR, Starkopf J, Kirsimägi Ü et al. (2014) Definition, prevalence, and outcome of feeding intolerance in intensive care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 58(8): 914-22.

PubMed ↗

Schmidt J, Stoffels B, Chanthaphavong RS et al. (2012) Differential molecular and cellular immune mechanisms of postoperative and LPS-induced ileus in mice and rats. Cytokine, 59(1): 49-58.

PubMed ↗

Singh G, Ram RP, Khanna SK (1998) Early postoperative enteral feeding in patients with nontraumatic intestinal perforation and peritonitis. J Am Coll Surg, 187(2): 142-46.

PubMed ↗

Steele SR (2007) Ischemic colitis complicating major vascular surgery. Surg Clin North Am, 87(5): 1099-114.

PubMed ↗

Taylor BE, McClave SA, Martindale RG et al. (2016) Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). Crit Care Med, 44(2): 390-438.

PubMed ↗

Valentine RJ, Hagino RT, Jackson MR et al. (1998) Gastrointestinal complications after aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg, 28(3): 404-11.

PubMed ↗

Valle RG, Godoy FL (2014) Neostigmine for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: a meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 3(3): 60-4.

PubMed ↗

Van Damme H, Creemers E, Limet R (2000) Ischaemic colitis following aortoiliac surgery. Acta Chir Belg, 100(1): 21-7.

PubMed ↗

van der Spoel JI, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Stoutenbeek CP et al. (2001) Neostigmine resolves critical illness-related colonic ileus in intensive care patients with multiple organ failure—a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Med, 27(5): 822–7.

PubMed ↗

van der Spoel JI, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Kuiper MA et al. (2007) Laxation of critically ill patients with lactulose or polyethylene glycol: a two-center randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med, 35(12): 2726–31.

PubMed ↗

van Zanten AR (2013) Nutrition barriers in abdominal aortic surgery: a multimodal approach for gastrointestinal dysfunction. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 37(2): 172-7.

PubMed ↗

Vermeulen Windsant IC, Hellenthal FA, Derikx JP et al. (2012) Circulating intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as an early marker of intestinal necrosis after aortic surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Surg, 255(4): 796-803.

PubMed ↗