ICU Management & Practice, ICU Volume 14 - Issue 2 - Summer 2014

Author

Shirish Prayag, MD, FCCM

Chief Consultant in Critical Care Medicine

Shree Medical Foundation, Pune, India

ICU Management Editorial Board Member

[email protected]

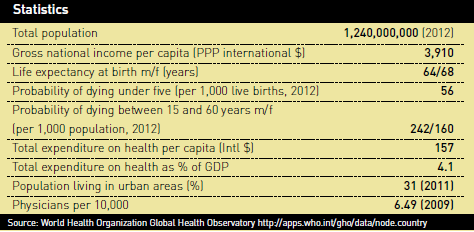

Critical care in India has grown from a relatively small body of professionals to a fully-fledged active speciality. The Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine publishes a MEDLINE®-indexed monthly journal, hosts an increasingly popular annual congress, but more importantly runs an extremely successful training programme. All this has been a part of the phenomenal growth in the field of critical care in India. With a projected rise in medical tourism to India, critical care as a speciality is poised to grow even further. Future challenges will include giving the speciality a meaningfully socialist angle to serve the multitudes where critical care has not reached as yet. The era ahead seems promising and exciting

Introduction

The growth of the field of critical care medicine in India is a great story of how the economic changes in a country can lead to the evolution of a scientific subspecialty. It is a story of how the private hospital industry can accelerate the growth and development of a service-oriented sector in the community.

Like everywhere else in the world, critical care in India, in the beginning, was practised in major public hospitals as part of the general management of seriously ill patients, without being labelled as a separate service. Attempts to segregate seriously ill patients in specialised areas dedicated to advanced management began in 1968 with the development of coronary care units in Mumbai (Yeolekar 2008). Very soon the concept of attempting to save the life of a seriously ill patient with the help of a specialised unit consisting of special equipment and staff engulfed non-cardiac patients as well. The availability of ventilators was responsible to a significant extent for the development of this concept. The early 1970s saw the development of the first critical care units, again in Mumbai, dedicated to the management of critically ill non -cardiac patients as well ( Prayag 2002). These units, like most other units in the world, were being run by dedicated staff, who had interest and enthusiasm for this field.

Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine

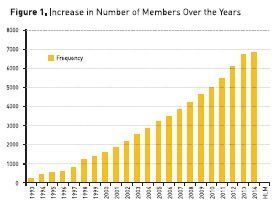

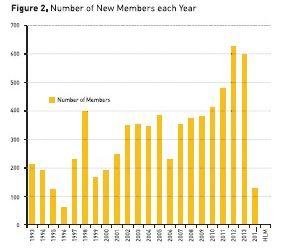

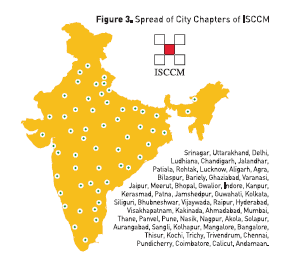

The real impetus for the development and evolution of this speciality came in the early 1990s. A group of physicians, back in various cities of India after training in the western world, started the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine (ISCCM) in 1993. Although it started off as a body of professionals, mainly for exchange of knowledge and discussions amongst the group, the leadership quickly realised that the main work it needed to do was to create an awareness of the speciality of critical care medicine. The popularity of the ISCCM can be seen from the growth in membership (see Figures 1 and 2) and the spread of the city units across the country over the last 20 years (see Figure 3). As of 2014, the membership stands at nearly 7000, and the number of city units is around 80.

Training

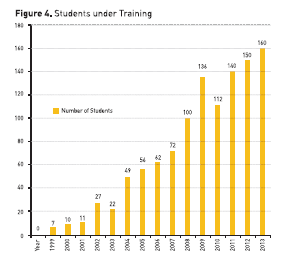

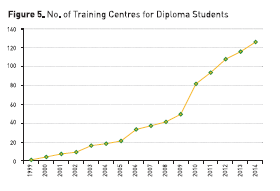

The need for developing a training programme for upcoming graduates was also felt quite strongly. Unfortunately, at that time in the 1990s, the universities and official licensing councils were not convinced about the need for developing a strong training programme in this upcoming speciality. ISCCM then took upon itself to start this training programme. It laid down the course curriculum, identification process of training institutes and their certification as well as a well structured exit examination. Initially a one-year certificate course was started, which soon evolved into a one-year diploma and a two-year fellowship course. Figure 4 shows the growth in the number of candidates registering for these courses over the last 16 years of these training programmes; Figure 5 shows the increasing number of training institutes for these courses.

The period of growth of the ISCCM coincided with the strong economic growth of India. The industrial policies of the country opened up, and as a result the healthcare sector grew significantly. The public sector, controlled by the government, has always been a smaller player in healthcare delivery in India. Private healthcare organisations, predominantly for-profit organisations, form almost 80% of the total healthcare delivery sector (Prayag 2004). Because of the extra cost of equipment and specialised manpower, critical care is a hospital segment, which is heavily driven by high-end economics, and the growth in the critical care sector in India over the last two decades has been essentially in private sector organisations. The exact number of ICU beds in India is not available, since the registration of ICUs and hospitals is not a centralised process. There appears to be a shortage of beds in hospitals in most parts of the country compared to the population, the demands and also to western standards (Yengkhom 2013). With the increasing development of large multi-speciality hospitals and the growing penetration of health insurance, this deficit is expected to be reduced significantly over time. The centralised National Board of Medicine in India and the Medical Council of India approved the critical care training programmes only recently, and these are currently run in a limited number of centres in the country. The contribution of ISCCM is significant in this regard, since it could provide the bulk of a large number of trained specialists to staff these ICUs from the mid-1990s, at a time when there was a significant shortage of manpower.

Specialist Congresses with International Experts

One of the other major contributions in the growth of this speciality in India has come from the annual national congresses of ISCCM, which have been extremely successfully conducted over the last 20 years in various parts of the country. Many international stalwarts in the field of critical care have presented their latest work to the Indian audience at these congresses. In an era when very few Indian specialists could attend International meetings such as ISICEM, ESICM or SCCM, the presence of these specialists from all across the globe has done wonders to raise the scientific standards and act as appropriate role models for the average ICU physician of India. The currently started programme of “Best of Brussels” is also another significant step in the same direction since it carries the mini-programme of ISICEM into India.

Critical Care Research

Original research in critical care in India has been limited. Traditionally, Indian medical students have not been taught research methodology during medical school. The emphasis during training had always been on clinical medicine and patient care rather than research and publications. Despite the strong pool of good quality clinicians, original research therefore has been extremely poor in volume, as revealed by the fact that the SCOPUS database since 1977 revealed only 72 articles from India published in three major critical care journals (Divatia and Jog 2013). ISCCM has now developed its own research section, and data collection in various issues peculiar to ICUs across India has begun. The first corroborative study involving collection of data from Indian ICUs – INDICAPS – was presented in 2012. Indian ICUs have contributed significantly to data in various International studies, including EPIC II (Vincent et al. 2009) ICON, (Vincent et al. 2013), OSCILLATE, (Ferguson et al. 2013) PROWESS SHOCK (Ranieri et al. 2012), INICC data (Mehta et al. 2013) amongst others. Although this is a good beginning in the culture of research methodology, this really is not original work from India. Hence the Indian critical care community is now leaning towards making meaningful contribution towards the management of conditions peculiar to their subcontinent, and trying to publish this research. Patients with severe Dengue infections coming to ICU (Schmitz et al. 2011) or ARDS related to H1N1 epidemics managed with high frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) (Jog et al. 2013 ) are amongst the examples of contributions which the Indian intensive care community is trying to make in the world of critical care. These kind of contributions will be extremely meaningful given the volumes of case material available in India and the maturing research abilities of the Indian critical care community.

Publications

The Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine (http://www.ijccm.org) was established in 1996, and has been indexed in MEDLINE® since 2007. It has evolved to become a strong representative mirror of the work of the critical care community in India. It is now published monthly, and gets a large number of articles from outside the Indian subcontinent. ISCCM has other publications, including a newsletter Critical Care Communications, an ICU protocol book, audio journal series podcast and now a textbook called the ICU Book. It has also published numerous guidelines (e.g. on catheter-related bloodstream infections, management of tropical infections, end-of-life care, ICU planning and designing in India etc.) (Mani et al. 2012). These are substantial contributions to evolve the critical care community in India to a group of committed, meaningful, scientific group of physicians.

Conclusion

The increasingly important role of the Indian critical care community is being recognised all over the world. An Indian representative was elected on the Council of the World Federation of Societies for Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (WFSICCM) for the first time in 2001, and since then India continues to be present in the council. Asia Pacific critical care also has a significant contribution from India. An Indian consultant has become the Asia Pacific representative on the council of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). India is now represented on the editorial boards of prestigious International journals like Intensive Care Medicine, ICU Management and Critical Care (in future).

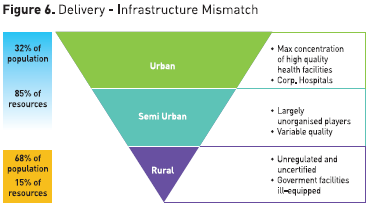

Critical care in India has evolved very rapidly and significantly in the last two decades of its existence. Not only has the number of ICUs and the number of properly equipped beds increased, but the trained manpower has increased leaps and bounds. More importantly, there has been a meaningful pragmatic direction to this movement to make sure that this growth is in an extremely scientific, academically oriented atmosphere. Where will all this lead to in the future ? India is gearing up for a possible meaningful change in political leadership. This could add substance to the numerical economic growth which it has been experiencing. This meaningful growth, if and when it happens, will hopefully reach the multitude of masses which are still struggling below poverty line. A strong socialistic direction is needed in the modern way to really service the masses of critically ill patients struggling to get high quality care due to prohibitive costs (see Figure 6). Hopefully, India will be able to achieve a balance in the progress and its appropriate distribution. Unless that happens, critical care would remain a relatively exclusive service for the minority who can afford its ever increasing costs. This perhaps is the biggest challenge for the Indian critical care community for the future. Either way, we look forward to interesting and exciting times ahead.

For full references, please email [email protected], visit the website at www.icu-management.orgor use the QR code at the top of the article