ICU Management & Practice, Volume 23 - Issue 2, 2023

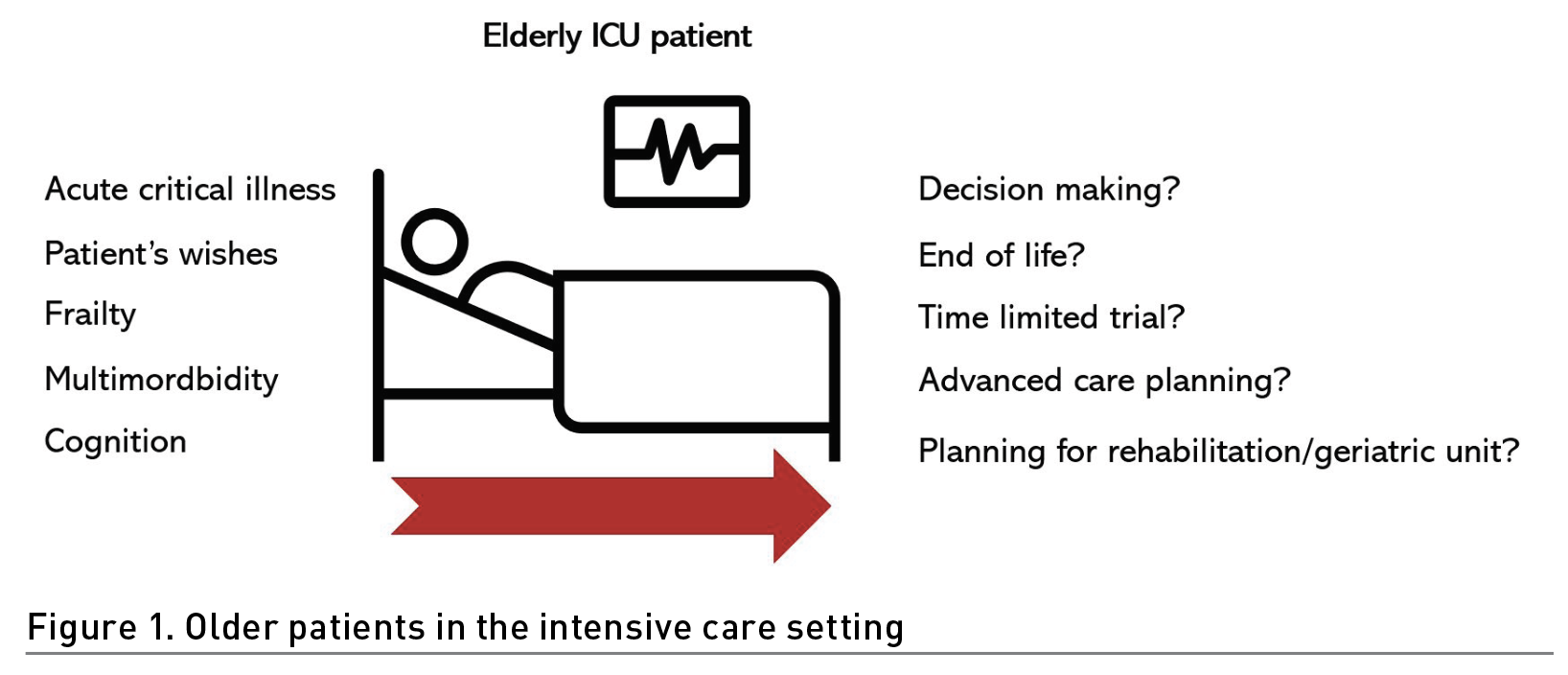

Treating an elderly patient in intensive therapy requires the integration of many components. The purpose of this paper is to promote a comprehensive assessment of the critically ill patient aged 80 or more years.

Introduction

Ageing of the population combined with a shortage of intensive care unit (ICU) beds results in a demand for intensive care continuously outstripping supply of resources even in highly developed healthcare systems (Guidet et al. 2017). At the same time, the invasiveness and high cost of ICU procedures necessitate careful decision-making in regard to patients who may or may not benefit from admission to the ICU. Such issues are especially relevant in the case of critically ill patients over 80 (Guidet et al. 2018). Accumulation of chronic diseases, depletion of biological reserves, cognitive impairment, and malnutrition are inseparably associated with ageing. In older adults, critical illness often occurs in the context of a baseline depletion of physiologic reserves, not only posing a medical challenge, but also raising ethical questions about patients’ willingness to receive aggressive treatment which may prove futile in the end (Boumendil et al. 2011). Long-term outcomes after intensive care are strongly determined by pre-ICU functional trajectories (Ferrante et al. 2015). Hence, a complex assessment of a patient's health may enhance clinicians’ ability to distinguish those who are most likely to benefit from hospitalisation in the ICU and to guide post-ICU treatment strategies. The purpose of this paper is to promote a comprehensive assessment of the critically ill patient aged 80 or more years.

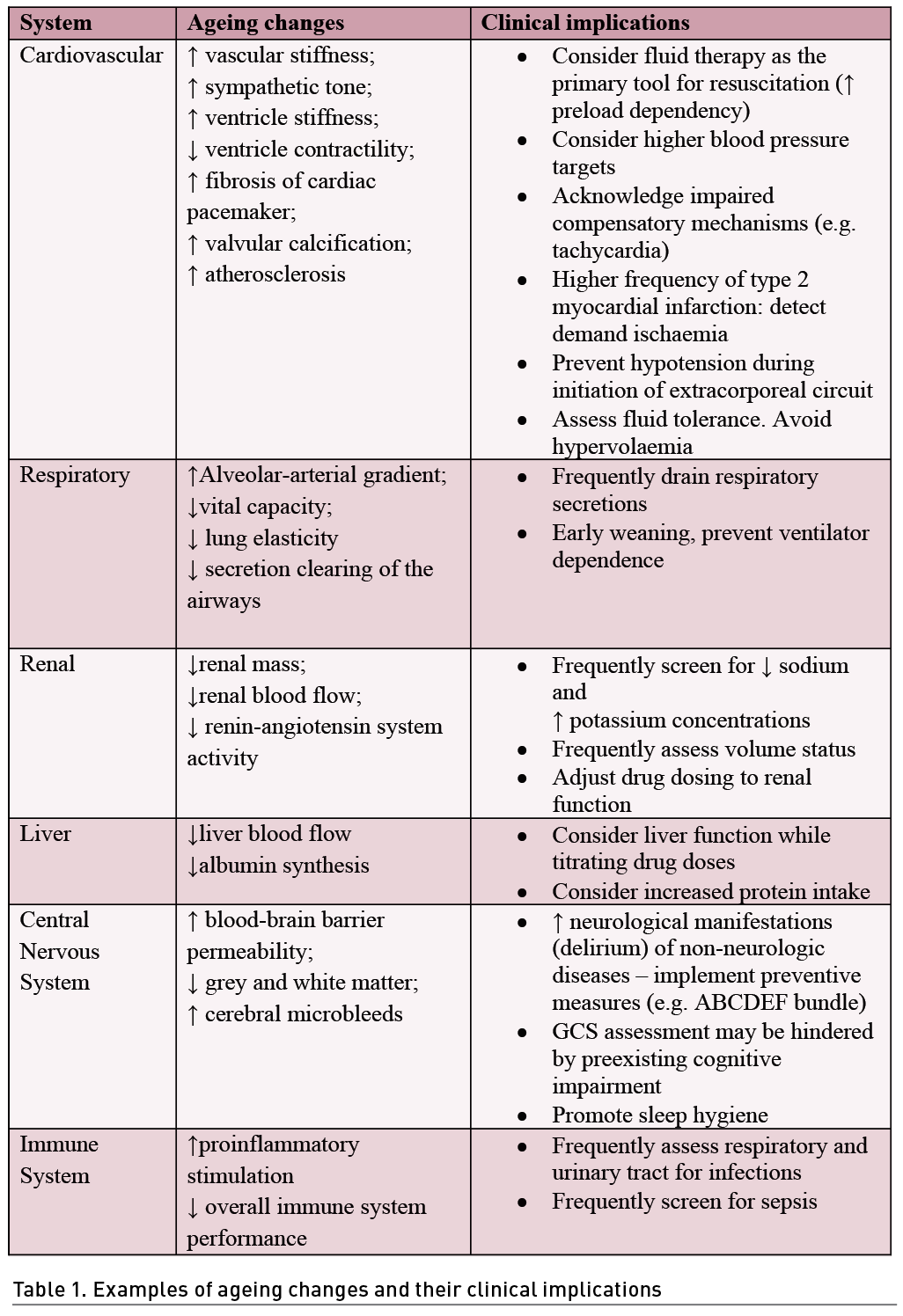

Acute Organ Dysfunction

The incidence of acute organ dysfunction increases with age (Flaatten et al. 2017a). Older patients are more likely to suffer from sepsis than the younger counterparts (Angus et al. 2001). This is usually closely related with acute respiratory failure which constitutes the primary cause for an urgent ICU admission in the older population (Flaatten et al. 2017b). The functional ageing of organs should be considered when treating acute critical illness (Brunker et al. 2023). Examples of such organ changes and the resulting clinical implications are shown in Table 1 (Brunker et al. 2023). The most popular tool used for the assessment of organ dysfunction is the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (Vincent et al. 1996). First introduced as a tool to describe the severity of organ dysfunction, it was later found to be well correlated with mortality (Lopes Ferreira et al. 2001). Despite a number of caveats (Lambden et al. 2019), SOFA score continues to be a globally utilised universal method for multi-organ failure assessment. With the introduction of the VIP (very old intensive care patients) network, a number of large observational studies have been conducted in this population (Van Heerden et al. 2021). For example, in the VIP-1 study (5021 patients), one-point increase in submission SOFA score was independently associated with 30-day mortality: a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.13 (1.12-1.14) (Flaatten et al. 2017b). In a subsequent VIP-2 study (3920 patients), one-point increase in SOFA produced a similar HR of 1.15 (1.14-1.17) (Guidet et al. 2020). Moreover, in a cluster analysis of the VIP-2 and COVIP studies, the authors derived seven different phenotypes based on SOFA, SOFA sub-scores, age, and geriatric features (Mousai et al. 2022). The phenotype based on the highest SOFA score produced a 30-day mortality of 57% compared to 17% in patients with lower SOFA score. Interestingly, the phenotype based solely on the oldest age was associated with an excellent prognosis (30-day mortality of 2%).

Frailty

Frailty is defined as a state of decreased physiologic reserve that heightens vulnerability to acute stressors (Chen et al. 2014). Older patients, who are most susceptible to frailty, often exhibit various degrees of decreased mobility, weakness, sarcopenia, malnutrition, and impaired cognition (Muscedere et al. 2017). Importantly, a stay in the ICU may be associated with an exacerbation in the above pathologies due to neuropathy, increased catabolism and inflammation (Shepherd et al. 2017; Van Gassel et al. 2020; Paul et al. 2020). Undergoing critical illness may then be associated with ICU-acquired weakness which aggravates the already existing functional impairment (Vanhorebeek et al. 2020). Frailty increases mortality and prolongs ICU and hospital stay with increased use of organ support (Muscedere et al. 2017). The evaluation of frailty on admission to the ICU requires the use of a validated scoring system. One of the simplest and most-utilised tools in critical care research is the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (Rockwood et al. 2005). The CFS, being a 9-point scale, stratifies patients based on their functionality. For example, a CFS grade of 1 describes a very fit patient who exercises regularly and is not dependent on any personal assistance. On the other hand, a grade of 8 corresponds to a person who is very severely frail, who is completely dependent and is approaching the end of life. Commonly, CFS ≥5 is regarded as clinical frailty (Church et al. 2020). Using this threshold, it has been observed that frailty is present in 46% of acutely admitted elderly ICU patients (Flaatten et al. 2017b). One-point increase in CFS is associated with a 30-day mortality HR of 1.11 (1.08-1.15) (Guidet et al. 2020). Importantly, frailty should not be diagnosed as "present" or "absent" - different grades of CFS have different prognostic implications, thus no single threshold discriminating patients who are “frail” from those “fit” can be deemed optimal. In sum, frailty contributes up to 9% of new prognostic information about 30-day mortality after adjusting for basic patient characteristics (Fronczek et al. 2021).

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity is a state in which two or more chronic diseases overlap (Salive 2013). Older age is the single most important risk factor accounting for multimorbidity. Hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiac failure are most common diseases in older, multi-morbid patients (Salive 2013). An average patient over 80 years old struggles with roughly three chronic diseases (Barnett et al. 2012). Since multimorbidity is not a homogeneous entity, different disease-constellations determine different outcomes (Zador et al. 2019). Importantly, accounting for comorbidities improves prognostication in critical care (Nielsen et al. 2019). One of the validated tools to assess the grade of multimorbidity is the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (Charlson et al. 1987). In the ICU population, CCI has been shown as a valuable addition to predicting both in-hospital, 30-day or 1-year mortality, even after accounting for acute physiology scores (Zampieri and Colombari 2014; Stavem et al. 2017). In a study by Zampieri et al. (2014), an increase in 1 point in CCI corresponded with mortality odds ratio of 1.16 (1.07-1.27). Multimorbidity is often associated with polypharmacy, which is a risk in itself. For example, imposition of sepsis on an elderly patient receiving beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and paracetamol may not only hinder a rapid diagnosis, but also may impair certain compensatory mechanisms (e.g. tachycardia during vasodilation or renal vasoconstriction during relative hypovolaemia). Interestingly, in the VIP-2 study, accounting for polypharmacy (by using the Co-morbidity and Polypharmacy score) made it easier to single out those with a poorer prognosis but did not add any prognostic value to a model containing age, SOFA score, ICU admission diagnosis and frailty.

Cognition

Preexisting cognitive impairment (CI) may be present in over 40% of elderly patients admitted to the ICU (Pisani et al. 2003). CI assessment is difficult in the setting of acute critical illness. Critically ill patients are often exposed to various sedative and analgesic agents that may (at least temporarily) aggravate the already existing CI. Knowledge of the presence and severity of CI can be obtained either from medical history, from relatives or measured by the clinician [e.g. by using IQCODE score (Jorm 2004)]. Usually, IQCODE > 3.5 indicates cognitive decline. Interestingly, this score can be estimated by interviewing close family members, as done in the VIP-2 study (Guidet et al. 2020). In their study, cognitive decline was present in 30% of elderly patients. Greater cognitive decline was associated with 30-day mortality. However, calculation of frailty alone added just as much prognostic value as frailty and cognition measured together, which indicates close relationship between these two entities. Indeed, frail patients are more often found to have a preexisting CI (Sanchez et al. 2020). Nevertheless, CI is a strong vulnerability factor for delirium (Krzych et al. 2020), which is a known and independent risk factor for mortality and long-term cognitive impairment (Pandharipande et al. 2014). Prevention of delirium improves patient outcomes (Kotfis et al. 2022). One strategy for avoiding delirium is to implement the ABCDEF bundle which underlines the importance of pain management, rapid extubation, non-use of benzodiazepines, routine delirium screening (e.g., CAM-ICU), early mobilisation and family support (Marra et al. 2017). In the elderly, implementation of such measures may be more challenging due to the preexisting CI (impaired communication), frailty (delayed mobilisation) or higher baseline pain due to immobility (Brunker et al. 2023). Importantly, choosing dexmedetomidine over propofol as a sedative drug has shown promise in reducing delirium incidence in the older population (Pereira et al. 2020).

Patient Wishes

Patient-centred care requires a deep understanding of patients' autonomy and wishes. Hospitalisation in the ICU can be one of the most traumatic experiences in a patient's life, and surviving a critical illness can be just the beginning of long-term psychological and functional sequelae (Burki 2019). In a study by Heyland et al. among the survivors, after 6 months only one-third was independent for all activities listed in Katz’s scale (Burki 2019). Importantly, in the ETHICA study, elderly individuals were often reluctant to accept life-sustaining treatments, especially invasive mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy. This highlighted quality of life as a factor valued the most by these individuals (Philippart et al. 2013). Meanwhile, in the ICE-CUB study, only 13% of elderly ICU patients were asked about their opinion regarding the ICU treatment prior to ICU admission (Le Guen et al. 2016). Understanding the patient's wishes means that even if organ support can be discontinued, comfort measures cannot be withdrawn, and suffering should be avoided at all times (Vincent and Creteur 2022).

Conclusion

In summary, treating an elderly patient over the age of 80 in intensive therapy requires the integration of many components (Figure 1) (Guidet et al. 2018; Jung et al. 2023). At present, there is no single tool for describing the critically ill elderly patient. There is a lack of dedicated guidelines and sufficient evidence regarding the therapeutic management of such patients.

A comprehensive analysis of the patient's wishes, acute illness, multimorbidity, cognitive status and frailty can help clinicians take optimal action. In doing so, it is worth remembering that age alone should never determine our clinical decisions.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J et al. (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 29(7):1303-1310.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. (2012) Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 380(9836):37-43.

Boumendil A, Latouche A, Guidet B (2011) On the benefit of intensive care for very old patients. Arch Intern Med. 171(12):1116-1117.

Brunker LB, Boncyk CS, Rengel KF, Hughes CG (2023) Elderly Patients and Management in Intensive Care Units (ICU): Clinical Challenges. Clin Interv Aging. 18:93-112.

Burki TK (2019) Post-traumatic stress in the intensive care unit. Lancet Respir Med. 7(10):843-844.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 40(5):373-383.

Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX (2014) Frailty syndrome: An overview. Clin Interv Aging. 9:433-441.

Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O (2020) A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 20(1).

Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE et al. (2015) Functional trajectories among older persons before and after critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 175(4):523-529.

Flaatten H, de Lange DW, Artigas A et al. (2017a) The status of intensive care medicine research and a future agenda for very old patients in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 43(9):1319-1328.

Flaatten H, De Lange DW, Morandi A et al. (2017b) The impact of frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years). Intensive Care Med. 43(12):1820-1828.

Fronczek J, Polok K, de Lange DW et al. (2021) Relationship between the Clinical Frailty Scale and short-term mortality in patients ≥ 80 years old acutely admitted to the ICU: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 25(1).

Guidet B, van der Voort PHJ, Csomos A (2017) Intensive care in 2050: healthcare expenditure. Intensive Care Med. 43(8):1141-1143.

Guidet B, Vallet H, Boddaert J, et al. (2018) Caring for the critically ill patients over 80: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care. 8(1).

Guidet B, de Lange DW, Boumendil A et al. (2020) The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European ICUs: the VIP2 study. Intensive Care Med. 46(1):57-69.

Jorm AF (2004) The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): A review. Int Psychogeriatrics. 16(3):275-293.

Jung C, Guidet B, Flaatten H et al. (2023) Frailty in intensive care medicine must be measured, interpreted and taken into account! Intensive Care Med. 49(1):87-90.

Kotfis K, van Diem-Zaal I, Roberson SW et al. (2022) The future of intensive care: delirium should no longer be an issue. Crit Care. 26(1).

Krzych ŁJ, Rachfalska N, Putowski Z (2020) Delirium superimposed on dementia in perioperative period and intensive care. J Clin Med. 9(10):1-20.

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Ely EW (2014) Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 370(2):185-186.

Pereira J V., Sanjanwala RM, Mohammed MK et al. (2020) Dexmedetomidine versus propofol sedation in reducing delirium among older adults in the ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 37(2):121-131.

Lambden S, Laterre PF, Levy MM, Francois B (2019) The SOFA score - Development, utility and challenges of accurate assessment in clinical trials. Crit Care. 23(1).

Le Guen J, Boumendil A, Guidet B et al. (2016) Are elderly patients’ opinions sought before admission to an intensive care unit? Results of the ICE-CUB study. Age Ageing. 45(2):303-309.

Lopes Ferreira F, Peres Bota D, Bross A et al. (2001) Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 286(14):1754-1758.

Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, Patel MB (2017) The ABCDEF Bundle in Critical Care. Crit Care Clin. 33(2):225-243.

Mousai O, Tafoureau L, Yovell T et al. (2022) Clustering analysis of geriatric and acute characteristics in a cohort of very old patients on admission to ICU. Intensive Care Med. 48(12):1726-1735.

Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A et al. (2017) The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 43(8):1105-1122.

Nielsen AB, Thorsen-Meyer HC, Belling K et al. (2019) Survival prediction in intensive-care units based on aggregation of long-term disease history and acute physiology: a retrospective study of the Danish National Patient Registry and electronic patient records. Lancet Digit Heal. 1(2):e78-e89.

Paul JA, Whittington RA, Baldwin MR (2020) Critical Illness and the Frailty Syndrome: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Anesth Analg. 130(6):1545-1555.

Philippart F, Vesin A, Bruel C et al. (2013) The ETHICA study (part I): Elderly’s thoughts about intensive care unit admission for life-sustaining treatments. Intensive Care Med. 39(9):1565-1573.

Pisani MA, Inouye SK, McNicoll L, Redlich CA (2003) Screening for preexisting cognitive impairment in older intensive care unit patients: Use of proxy assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 51(5):689-693.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C et al. (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. C Can Med Assoc J. 173(5):489-495.

Salive ME (2013) Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 35(1):75-83.

Sanchez D, Brennan K, Al Sayfe M et al. (2020) Frailty, delirium and hospital mortality of older adults admitted to intensive care: the Delirium (Deli) in ICU study. Crit Care. 24(1).

Shepherd S, Batra A, Lerner DP (2017) Review of Critical Illness Myopathy and Neuropathy. The Neurohospitalist. 7(1):41-48.

Stavem K, Hoel H, Skjaker SA, Haagensen R (2017) Charlson comorbidity index derived from chart review or administrative data: Agreement and prediction of mortality in intensive care patients. Clin Epidemiol. 9:311-320.

Van Gassel RJJ, Baggerman MR, Van De Poll MCG (2020) Metabolic aspects of muscle wasting during critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 23(2):96-101.

Van Heerden PV, Beil M, Guidet B et al. (2021) A new multi-national network studying very old intensive care patients (vips). Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 53(4):290-295.

Vanhorebeek I, Latronico N, Van den Berghe G (2020) ICU-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med. 46(4):637-653.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J et al. (1996) The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 22(7):707-710.

Vincent JL, Creteur J (2022) Appropriate care for the elderly in the ICU. J Intern Med. 291(4):458-468.

Zador Z, Landry A, Cusimano MD, Geifman N (2019) Multimorbidity states associated with higher mortality rates in organ dysfunction and sepsis: A data-driven analysis in critical care. Crit Care. 23(1).

Zampieri FG, Colombari F (2014) The impact of performance status and comorbidities on the short-term prognosis of very elderly patients admitted to the ICU. BMC Anesthesiol. 14.