HealthManagement, Volume 16 - Issue 4, 2016

How and Why Standardization Can Help Healthcare Providers Improve Quality and Increase Efficiency

Standards can improve efficiency, particularly in complex areas such as healthcare. Standardized clinical pathways are increasingly influencing the debate about sustainable, affordable, and efficient healthcare. Proven, standardized procedures can make the quality of care more measurable and reproducible for providers, patients, and payers.

Clinical Pathways: A Promising Instrument for Managing Quality

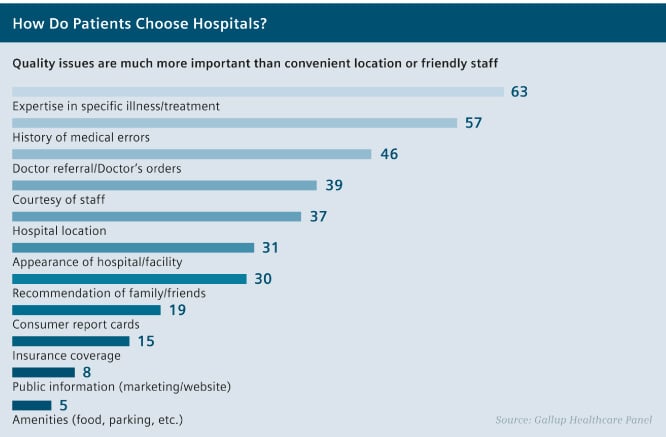

Patient surveys indicate that quality of care is a decisive criterion when choosing a hospital.1 For many years now, quality related selection factors such as expertise in a specific illness or treatment and the history of low numbers of medical errors top the list from the patient’s perspective.2 Therefore, the quality of healthcare influences occupancy and the commercial success of a hospital. Accordingly, systematic quality management is an important task. Improvements along clinical pathways can positively influence the quality of care. This makes enhancing the pathway a promising focus for achieving reliable, reproducible care improvements in daily routines.Evidence of this can be found all over the world. For example, a 2014 study of cancer patients at Xi’an general hospital in China produced impressive results. A specific clinical pathway was designed to standardize the treatment processes of partial hepatectomy (removal of the liver) for patients with HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver cell carcinoma). In all areas of postoperative outcomes – total complications, mortality, and readmissions – the results were clearly in favor of the patients who were treated according to the clinical pathway, as opposed to the patients who were not.3

Quality of Care: Large Differences, Poor Transparency

The concept of defining clinical pathways has existed since the 1980s in healthcare systems worldwide. Despite promising results from various projects, the concept has only recently received widespread attention in conjunction with the buzzword “evidence-based practice.”

The reason for this is growing economic pressure: In the interests of sustainable, cost-effective healthcare, resources must be used as effectively and efficiently as possible. Therefore, hospital financing is strongly linked to objective, verifiable quality criteria, such as successful surgeries or treatment and readmission rates. Current examples of specific initiatives include Germany’s Hospital Structure Act, and the Affordable Care Act in the U.S.

Indeed, there is a need for action on quality of care. There are significant differences in the quality of treatment between developed countries on the one hand and emerging or developing countries on the other. This is reflected in, for example, the survival rates of cancer patients. For breast and prostate cancer patients, the home country seems to be a factor in their survival, since sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic options do exist, but not necessarily in all countries. In many countries, there is a call for reliable quality standards from payers, government officials, and patients’ organizations. Figures from the German Cancer Society (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, DKG) confirm the contribution that quality standards can make to better patient care. They indicate that the society’s approximately 950 certified cancer centers achieve significantly higher survival rates than many of the non-certified hospitals.6,7 In the future, German hospitals must therefore expect deductions or could even be completely excluded from providing some health services if they fail to reach a certain number of cases or if they permanently fall below a defined minimum standard, which would indicate that they do not provide adequate treatment quality. For hospital managers, therefore, it is increasingly becoming an existential matter to prove their hospital’s quality of care by means of evaluation criteria.

Managing Complexity

through Evidence-Based Standards

Wherever standards and guidelines serve as a basis for treatment, it is important to develop them using the best possible evidence and to regularly review them using reliable measurement and comparative data. The collection and evaluation of appropriate datasets often involves considerable additional work for employees.5 Thus, in the interests of having the broadest and most up-to-date database possible, hospitals could rely on routine data, i.e., data they have to collect anyway for billing purposes or official health statistics. This significantly reduces the burden on the staff compared to using separately developed process indicators, and increases the willingness to cooperate.

Evidence-based standards not only improve cost efficiency, but can also help doctors make decisions, avoid medical errors and omissions, explain therapeutic decisions to patients, and can support high-quality care. For example, Helios, a German hospital chain, has relied on structured quality management and continuous improvement processes for many years. As part of the Initiative for Quality Medicine (IQM), the quality indicators developed by Helios for its companies are now also used in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland by numerous hospitals outside the group.8 Ideally, participating providers can use the figures to compare efficiency across institutions, and the IQM process to manage quality and derive optimum treatment paths.

Limitations and Challenges

For doctors and patients, the introduction of standards in combination with increasing economic pressure also leads to misgivings. Many doctors fear that standardization will restrict them in their individual treatment decisions. And patients are worried that they will not receive individualized – and therefore maybe more expensive – therapy. To enforce standards within healthcare facilities, resolute and well-thought-out change management is required. One important prerequisite for success in standardization projects is that providers persuade everyone involved of the benefits and motivate them to participate.9

Even with clinical guidelines in place, a doctor’s individual clinical decision-making and individual opinions about the patient will still be needed in the future. This is particularly true in regard to the increasing number of patients with multiple chronic diseases, for whom using various clinical guidelines developed for single diseases may have adverse effects.5 Decisions must continue to be made individually and sometimes subjectively if there is insufficient empirical knowledge to secure a specific clinical pathway. To apply evidence to a specific patient care situation, the clinician needs evidence plus good judgment, clinical skills, and knowledge of the patient’s unique needs

In a Nutshell

Standardization Challenges in Healthcare

- Standardization does not aim solely at lowering costs, but

first and foremost at ensuring reliable, high-quality results. This makes it a

key issue for providers, payers, and patients.

- Standardized clinical pathways can make quality of care more

measurable and reproducible for providers, patients, and payers, supporting

more consistent, reliable treatment decisions.

- For standardization projects to succeed, hospital managers

must actively address the concerns of clinical staff and patients, persuade all

parties, and motivate them to participate.

- In view of rising

costs and the existing differences in quality, payers, government officials and

patients’ organizations in many countries are calling for reliable quality

standards. For hospital managers, they are increasingly becoming a matter of

survival.

- Evidence-based standards and guidelines can provide support

to doctors in making complex decisions, help them avoid medical errors and omissions,

and help ensure that all patients get a consistently high quality of treatment.

- Existing standards and guidelines should be subjected to

regular empirical reviews and adapted to current findings. Rules that are based

solely on tradition, or pragmatic consensus can endanger the quality of care.

References:

- Bertelsmann Stiftung und Barmer/GEK, Gesundheitsmonitor

2012, www.gesundheitsmonitor.de

- Gallup Healthcare Panel, 2005, www.gallup.com

- The Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, Vol. 15,

2014

- The Lancet, Vol. 385, No. 9972, 2015

- Institute of Medicine, Mark Smith (et.al.), Best Care at

Lower Cost, 2013

- AOK Bundesverband, Pressemappe zum Krankenhaus-Report 2015,

www.aok-bv.de

- Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Zentrenmodell,

www.krebsgesellschaft.de/deutschekrebsgesellschaft/zertifizierung.html

- Health Leaders Media Industry Survey 2015

- Healthcare Information and Management Society (HiMSS),

Healthcare Provider Innovation Survey, 2013, www.himss.org