HealthManagement, Volume 23 - Issue 3, 2023

Procurement plays a crucial role in achieving affordability and profitability in the healthcare sector. With ever-rising healthcare expenditures, the focus on procuring products and services efficiently and effectively is essential. Collaboration between healthcare providers as buyers and with their suppliers is vital. By embracing a broader notion of responsible procurement, healthcare providers can promote innovation, sustainability, and better healthcare outcomes for all.

Key Points

- Procurement is a crucial lever for achieving affordability and profitability in the healthcare industry.

- Collaboration on many fronts is essential.

- Dealing with the systemic challenges highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic requires systemic change.

- This, in turn requires a new market- (not just supplier-) oriented perspective on responsible procurement

Healthcare Procurement – An Important Lever for Affordability

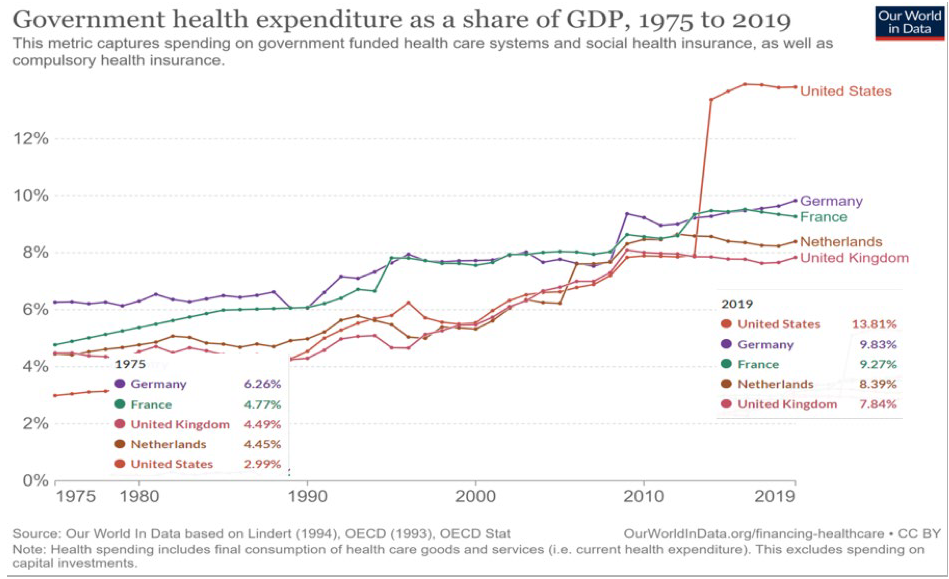

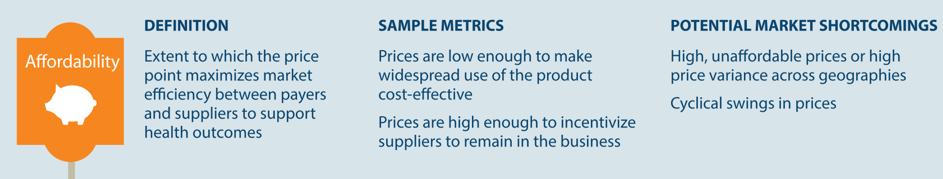

Healthcare expenditure is high, ever-rising, and playing an ever-greater part in the economy (Figure 1). Typically, after payroll, the second largest expense for healthcare providers is product acquisition and services, at some 30-50% of annual budgets. So, we cannot discussaffordability and profitability in healthcare without paying close attention to the suppliers of products and services and procurement effectiveness. Procurement strategies and practices directly influence costs and consequently quality and innovativeness of care. Even the smallest changes in how and what products and services are bought by healthcare providers can significantly impact the healthcare system and its affordability.

Figure 1: Rising health expenditure as a share of GDP, 1975 to 2019. Source: Our World in Data

The bar is rising for procurement teams in healthcare. Pressures are increasing, driven by multiple factors, including outsourcing of services, rising supplier prices (a function of costs and profits) and changing patterns of care enabled by the adoption of new technologies. It’s worth noting that procurement in healthcare has tended to lag behind that of other sectors (e.g., the automotive industry) in mobilising suppliers. Leading manufacturers invest in procurement because it plays a vital role in delivering the firm’s innovation strategy and long-term competitive advantage. A similar logic applies even where profit is not the buying organisation’s primary motive. Rather than gaining an advantage over competitors, the ‘advantage’ being sought relates to delivering better health outcomes for the wider communities served.

Recent systemic shocks, such as COVID-19, have provided new insights into long-running, deep-rooted procurement and supply chain management (PSCM) challenges. Based on our own recent research and insights from research in other sectors, in this article, we argue that buyers need to cooperate with others in the supply chain, collaborating in various ways both with other buyers and suppliers. We review some more conventional approaches to securing affordability and value with and from suppliers and advocate some less well-established approaches.

The Basics of Collaboration—Levels and Axes of Collaboration (and Rivalry)

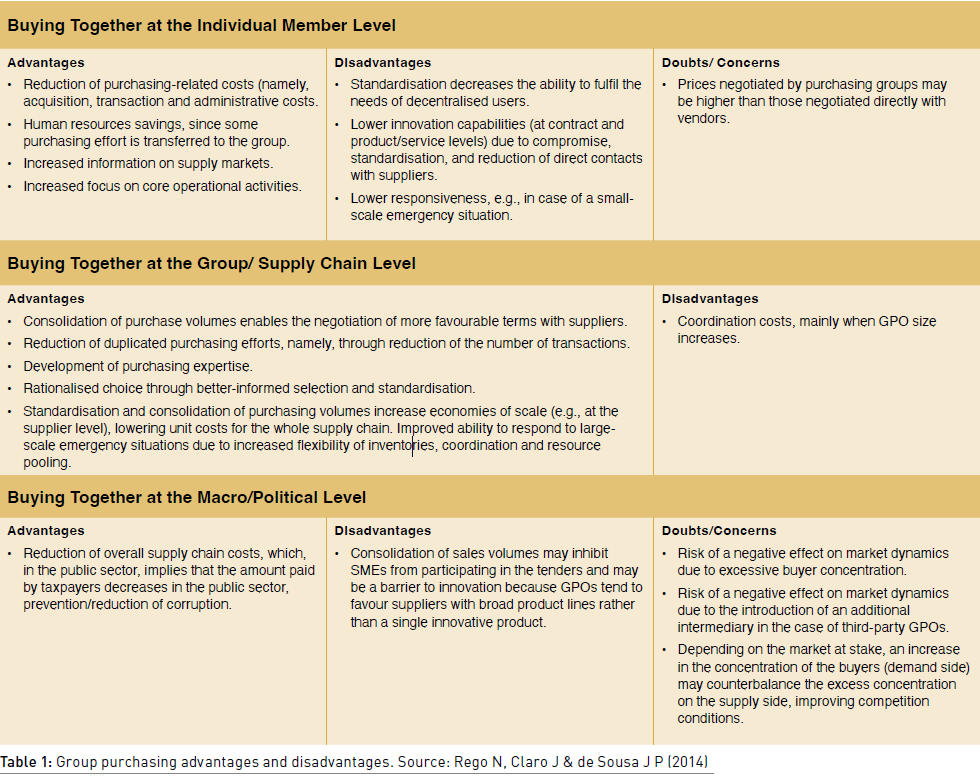

The value of group purchasing organisations (GPOs) is widely recognised. Better prices and lower transaction costs are primary motivations for joint buying, but there are also significant risks and drawbacks at various levels in the system (Table 1). Some of the concerns are the long-term, market-level consequence of decisions which – at the level of the individual care provider – yield short-term price benefits.

Learning from Crises— The Collective Influence of Buyers on Markets

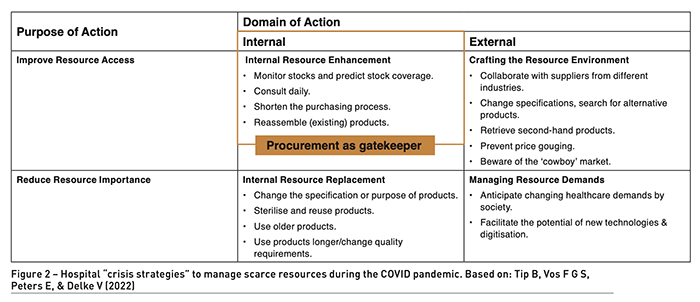

The COVID-19 crisis led to a great many lessons in PSCM. Research provides insights into the 5Rs (refuse, reduce, reuse, repurpose, recycle) and better ways of working in times of resource scarcity. Figure 2 summarises various strategies that stakeholders followed during the pandemic to ensure the security of supply and demonstrates the key role played by procurement in improving resource access. Dysfunctional allocation of resources was found at several hospitals studied, with individual departments stockpiling supplies, at the expense of other departments experiencing scarcity. The intervention of procurement professionals at the intra- and inter-hospital level resolved helped distribute the product fairly within the system. At the interorganisational level, price-gouging and counterfeiting by suppliers, governments ‘hijacking’ of supplies, unchecked rivalry between buyers and inventory hoarding were just some of the problems encountered by healthcare institutions. There were multiple points of system failure.

Contracting for personal protective equipment and vaccines brought PSCM, as well as buyers’ successes and failures and companies’ (anti)competitive practices, to the public’s attention. That attention continues today due to rising inflation and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. More questions are being asked about suppliers’ pricing strategies and profit levels, especially given evidence that in some sectors, rising profit levels are associated with rising dividends (and, conversely, falling wages and salaries) rather than rising R&D spending.

In combination with compelling evidence of rising market concentration in many sectors, this implies healthcare leaders need to take account of trends in supply market competitiveness, profit levels and value appropriation when looking at the (un)affordability of healthcare in the long term.

These factors are not just matters for regulators, but also for healthcare providers collectively, as the buyers in the market. It is in buyers’ common interest to act today in ways which promote healthy markets in the future – that is, markets in which sufficient suppliers compete effectively and consistently to reliably deliver high-quality products at a reasonable cost with fair profits and with an acceptable rate of innovation. Suppliers’ market barriers to entry and exit, and buyers’ switching costs, should be low enough to sustain market diversity and dynamism without leading to chaotic churn.

A key role for procurement could be what we call ‘market stewarding’ by buyers: first, recognising that today’s (individual) buying decisions create tomorrow’s markets and then actively anticipating how buying decisions and practices may shape those markets in the longer term. Only then is it possible to identify options for action which can influence the development trajectory of the market towards a more competitive, healthy, and dynamic ecosystem for the long-term advantage of all buyers in the market (and most suppliers, though not those which would seek to unfairly exploit their market dominance). Joint market consultations to promote innovation would be one such option, though market stewarding is also relevant to many other supply situations. Market stewarding is very much future-focused and concerned with promoting positive developments. It also relates to tackling problems in the market, as outlined next.

Tackling Excessive Profits and Unacceptable Practices

Procurement also has a role to play in directly addressing market failures, unfair value distribution and questionable practices. These are rife in many sectors, including – and some would say especially – in healthcare. For example, recent media has highlighted excessive profits, particularly concerning vaccines (Buchholz 2021) and energy (King 2023).

A study focusing on leading pharmaceutical companies revealed that their earnings as a fraction of revenue were almost double those of other S&P 500 Index companies (Buchholz 2021). Additionally, the largest MedTech firms enjoy profit margins ranging from 20-30% and impose widely varying prices for identical products in different countries. And yet, discussions about the impact of profit levels in markets and value distribution in supply chains on healthcare affordability and environmental impact are not common. In contrast, the need to protect companies’ margins to incentivise R&D and secure innovation is often emphasised (see example in Figure 3).

During the pandemic, extensive media coverage highlighted corruption and incompetence in healthcare PSCM, both on the buying and supplying side. When facing supply challenges such as personal protective equipment, chips, vaccines, and energy, governments often intervene, leveraging their political influence and economies of scale to manage turbulent markets. Excessive prices and supply (in)security motivate these reactive measures. While there is plenty of advice on recognising and addressing anti-competitive practices (e.g. from the OECD [OECD]), they mostly remain an undiscussed theme when developing procurement or debating healthcare affordability. To name a few examples of questionable practices (Knight 2023):

- Insisting buyers sign non-disclosure agreements, which prevents price benchmarking and facilitates price gouging.

- Buying up and then closing down innovative market entrants.

- Forcing customers to prematurely buy system upgrades and expensive staff training.

- Shielding profit increases behind talk of inflation.

- Realising increased profit through unethical marketing practices generates an ‘artificial’ demand for healthcare.

- Bid rigging.

- Prioritising wealth creation over health creation and care quality.

- Gaining price advantage by reducing costs through tax avoidance facilitated by complex ownership arrangements.

- Management strategies and financial practices which jeopardise basic services such as social care and core government services.

Procurement experts have a significant role to play in taking collective action to identify, assess, and tackle these harmful strategies. This is not instead of regulation but rather complementing it to promote genuine competition among suppliers. Procurement experts are well-placed to identify procurement policies and contracting strategies for addressing market entry barriers and barriers to switching and establishing appropriate and aligned incentives. The challenge for health executives and procurement leaders lies in ensuring that the essential resources within the buying functions are available, motivated, and skilled for additional, novel roles.

Conclusion

With ever-rising healthcare costs, we cannot talk about affordability and profitability in healthcare without talking about procurement and supply chain management. Recent crises have exposed multiple points of system failure, indicating the urgent need to rethink and reorganise how we manage (in) the system.

Based on government reviews and research, we argue that healthcare institutions can and should do more as buying organisations working together. Responsible procurement in healthcare can encompass more than improving social and environmental performance. It can also be about proactively addressing market-level issues, where these affect resource and value distribution, affordability, quality, sustainability, innovativeness, and, ultimately, healthcare outcomes.

Healthcare providers cannot combat the ever-rising healthcare expenditures by acting alone. By fostering an understanding of the challenges and aligning their efforts on strategic and structural solutions, they can more vigorously and effectively mobilise suppliers to adapt and develop to meet rising expectations, promote healthy markets, avoid the unchecked rivalry between buyers and tackle questionable practices by suppliers.

Post-script: At the European Lab for Innovative Purchasing and Supply (EL-IPS) at the University of Twente (NL), we are pursuing several lines of research in healthcare procurement to better frame and develop these ‘business-not-as-usual’ roles for procurement and evaluate their potential impact. The link below takes you to an overview of our current projects and recent findings and recommended reading/sources we have drawn on in preparing this article. The quality and value of management research depend on excellent dialogues with policymakers and managers – we would be very pleased to hear from readers! See the link or scan the QR code for our contact details.

Conflict of Interest

None. Profitability_Healthcare_25AugAA-web-resources/image/60.png)

References:

Best Practice Roundtables on Competition Policy. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/competition/roundtables.htm

Buchholz K (2021) How COVID-19 Vaccines Changed Pharma Company Profits. Statista. Statista Inc.

European Laboratory of Innovative Purchasing and Supply at the University of Twente (2023) University of Twente. Available: https://www.utwente.nl/en/bms/el-ips/

Healthy Markets for Global Health: A Market Shaping Primer (2014) USAID’s Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact (CII). Available: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/healthymarkets_primer.pdf

King B (2023) Why are BP, Shell, and other oil giants making so much money right now? BBC News. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-64583982

Knight L (2023) Future Procurement We Need to Talk About Markets. University of Twente. Available: https://www.utwente.nl/en/academic-ceremonies/inaugural-farewell-lectures/booklets/booklets-2022-2023/inaugural-lecture-booklet-professor-louise-knight-23-march-2023.pdf

Public healthcare expenditure as a share of GDP, 2019. Our World in Data. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/public-healthcare-spending-share-gdp

Rego N, Claro J, Pinho de Sousa J (2014) A hybrid approach for integrated healthcare cooperative purchasing and supply chain configuration. Health care management science, 17, 303-320.

Tip B, Vos F G S, Peters E, Delke V (2022) A Kraljic and competitive rivalry perspective on hospital procurement during a pandemic (COVID-19): a Dutch case study. Journal of public procurement. 22(1), 64-88.