HealthManagement, Volume 4 - Issue 1, 2010

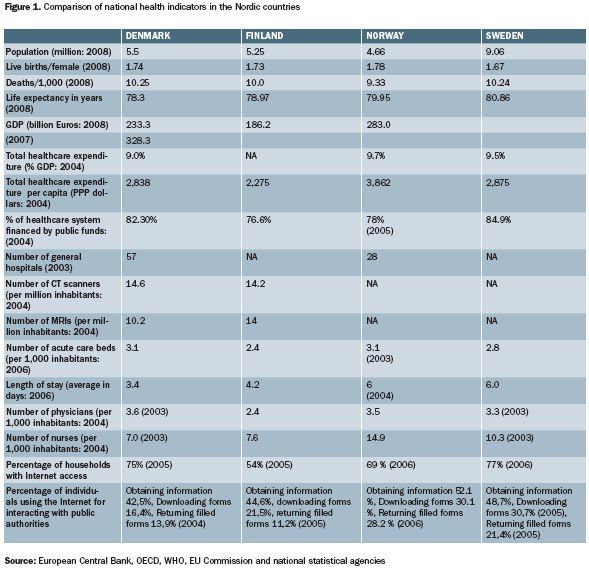

The Nordic healthcare system has a long heritage. It is especially well-established with regard to primary and preventive healthcare. These couple into sophisticated occupational health standards which are considered to be models by the outside world. All Nordic countries also have highly-developed hospital services. Nordic healthcare systems are taxation based, and locally administrated with every citizen having equal access to services. All countries, however, require co-payments by patients for hospital care and medicines. In general, the markets have a low level of influence on the functioning of healthcare systems. At a political level, equity and equality are important priorities. At the same time, productivity and efficiency are coming to the political agenda. In spite of a generally high level of commonality, there are some important differences in the Nordic region with regard to healthcare. Some of these are, moreover, growing as each country seeks to adapt to budgetary pressures and an ageing population. Explicit moves to cut down waiting times and improve hospital productivity have been made in Denmark and Finland. Variable user fees for hospitalisation are charged in Finland and Sweden. A brief description and overview of such issues in the four principal Nordic countries is provided below.

Denmark

Like the country itself, Denmark’s healthcare sector has three political and administrative levels: the State, the regions and the local municipalities. The healthcare service is organised in such a way that responsibility for services provided by the health service lies with the lowest possible administrative level. Services can thus be provided as close to the users as possible.

The Ministry of Health and Prevention was established on 23 November 2007 when the Ministry of the Interior and Health was separated into two.The Health and Prevention Ministry is in charge of administrative functions related to the organisation and financing of the healthcare system, psychiatry and health insurance as well as the approval of pharmaceuticals.

Earlier in 2007, local government reforms in January saw a system of 15 counties (including the metropolitan area) and 271 municipalities replaced by five regions primarily focused on the healthcare sector and 98 municipalities responsible for a broad range of welfare services.

Overall, within such a decentralised system, the State is responsible for legislation and supervision, while counties and municipalities are charged with operating health services (the former for hospital service and health insurance, and municipalities for other areas of healthcare, as well as nursing and child/school healthcare). Most hospitals are owned by the counties.

Some private hospitals have contracts with their county, while a handful of mainly small private hospitals operate outside the public hospital system. Specialist hospitals are not organised separately. Neither does Denmark have health centres with hospital beds.

GPs are the primary point of contact for patients except in an emergency, when they directly use hospital services. Specialist physicians work based on an agreement with a health insurance scheme, and most patients are referred to them by general practitioners.

To cut down waiting times, the Danish Government has been making supplementary allocations to health services since the turn of this decade. The sum has averaged DKK 1.2 billion a year, and has been rising steadily (it was DKK 1.4 billion in 2006). This has been combined with opening up possibilities for patients to receive treatment at private hospitals or certain accredited hospitals overseas, should waiting times be more than one or two months, respectively.

The reforms have had a significant impact. Waiting times for 18 major surgical procedures fell from 27 weeks in 2002 to 21 in 2005, and an estimated one of eight non-acute patients are now treated outside Denmark.

Since 2004 a move has been made to expand own management of funding by hospitals, with an eventual target of 50% of overall hospital allocations. Though this has led to some uncertainty about hospital budgets, it has contributed to increased efficiency and reduced waiting times.

The federal state block grant still constitutes the most significant element of financing – about 75%. In order to give the regions equal opportunities to provide healthcare services, the subsidy is determined by a number of criteria such as demographics, and the social structure of each region (the percentage of employed, the elderly, etc.).

Following the local government reforms of January 2007, one novelty is that the municipalities contribute to financing healthcare. The purpose is to encourage them to initiate efficient preventive measures for their citizens with regard to health issues.

Local financing consists of both a basic contribution and an activity-related contribution. Together they constitute approximately 20 percent of total financing of healthcare in the regions.

The basic contribution remains determined by the regions. The maximum limit is fixed by statute (DKK 1,500 per inhabitant at the price and wage level of 2003). The local basic contribution is initially fixed at DKK 1,000 per inhabitant.

The activity-related contribution depends on how much the citizens use the regional health services (hospitalisations and out-patient treatments at hospitals, as well as the number of services from general practitioners). In this way the municipalities that succeed in reducing the need for hospitalisation, etc. through efficient measures within preventive treatment and care will be rewarded.

Finland

Finland has a highly decentralised, three tier system of public healthcare, coupled to a much smaller private healthcare system. Physiotherapy, dentistry and occupational health services are the main areas covered by private care. Employers are legally obliged to provide occupational healthcare services for their employees.

Responsibility for healthcare is devolved to the municipalities (local government, according to the Public Health Act of 1972). Groups of municipalities run specialised central and regional hospitals. Municipalities are also responsible for providing health and social services for elderly people, including assisted living.

Primary healthcare is obtained from district health centres employing general practitioners (GPs) and nurses. These provide most day-to-day medical services and act as gatekeepers to more the more specialized services in the secondary and tertiary care sectors. Secondary/specialist care is also provided by the municipalities through district hospitals.

At the top of the hospital system in Finland is a network of five university teaching hospitals located in the major cities of Helsinki, Turku, Tampere, Kuopio, and Oulu. These provide tertiary care and contain the country’s most advanced medical expertise. The university hospitals are also funded by the municipalities, but supported by the national government.

The Finnish National Public Health Institute and the National Institute for Occupational Health are presently investigating the healthcare sector on issues concerning the structure and division of roles and responsibilities between the State, county councils and the municipalities.

In the public health service system, as mentioned, patients need a referral for specialist treatment, except in the case of emergency. At private clinics, however, patients need no referral to visit private specialists. Physicians working in private clinics can refer their patients either to public or private hospitals.

From March 2005, bar injury, patients are required to be examined and treated within a given time. Appointments have to be given within three working days. Treatment assessments have to be made within three weeks of referral to a hospital. In cases where treatment cannot be given at the first visit to the health centre, it is required to be started within three months, and within six months for specialised treatment. If a patient’s own health centre or hospital cannot provide treatment within the specified time limit, it has to be offered at another municipality or a private institution, at no extra cost to the patient.

Finland also has Europe’s first law on patients’ status and rights. This ensures a patient’s right to information, to informed consent to treatment, the right to see any relevant medical documents, and the right to autonomy. Backing this a Patient’s Injury Law, which gives patients the right to compensation for unforeseeable injury that occurred as a result of treatment or diagnosis. To receive compensation, it is sufficient that unforeseeable injury as defined by law occurred. This system has struck a balance between a litigious blame culture like the U.S. and the development of defensive medical practices as in many parts of Europe.

As principal providers of healthcare (accounting for two thirds of all spending), the municipalities are funded by national and local taxation. The balance third of spending is met by the national insurance system and private finance (either employer funded or by patients themselves). Barely 10 percent of the income of the private care sector comes from private insurance.

Though spending on healthcare is below the European average, the quality of healthcare service in Finland is high. According to a survey published by the European Commission in 2000, Finland has the highest number of people satisfied with their hospital care system in the EU: 88 percent of Finnish respondents were satisfied compared with the EU average of 41.3 percent.

Finland's National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and

Health is establishing a single, accessible, web-enabled repository for

healthcare indicators gathered from healthcare providers across Finland.

Norway

The State is responsible for healthcare policy and capacity issues as well as the quality of healthcare through budgets and laws. The State is also responsible for hospital services through regional health authorities who organise hospitals as health trusts. Municipalities have responsibility for primary healthcare, including both preventive and curative treatment. Regional health authorities and municipalities are free to operate public health services as they deem fit, although budgetary factor limit choices in the real world.

Private healthcare does not play a major role in Norway, due to the high standards and reach of the State system. Some private insurers offer complementary health insurance to those seeking to avoid hospital waiting lists or receive certain treatments such as cosmetic surgery. Private healthcare is also used for substance abuse, as well as dental treatment and certain forms of rehabilitation.

General practitioners (GPs) are gatekeepers in the Norwegian health system. GPs prescribe drugs and provide referrals to specialists and hospitals. They also treat acute and chronic illnesses, and provide preventive care. Citizens can choose the GP of their choice, but can change them up to a maximum of only two times a year. People seeking state medical care must make sure their GP is contracted into the State scheme; others require payment of full (rather than nominal) fees by the patients. Out of normal hours, GPs operate an oncall system. Specialist physicians are also referred to as consultants. GPs refer patients to a consultant if they need specialist diagnosis or intervention.

Norway has 80-plus hospitals located in major towns and cities. Patients are admitted to hospital either through the emergency department or via referral by their GP. Once admitted, treatment is the responsibility of a hospital doctor. In the rare cases where the Norwegian hospital system lacks the expertise to provide care, treatment is arranged overseas at no cost.

The Norwegian health system is funded predominantly through taxes taken directly from salaries. There is no specific health contribution fund. The Trygdeetaten (National Insurance Administration) is responsible for administering the State National Insurance Scheme (NIS), which guarantees everybody a basic level of health care and welfare (disability, unemployment, pension). All citizens and residents of Norway must contribute to the NIS.

In return, there are relatively few fees for using the State

system. Inpatient hospital treatment is free. However, visits to doctors and

specialists as well as purchases of prescription medicine incur small

copayments.So do radiology and laboratory tests. There are nevertheless a

number of exemptions, not least those afflicted by chronic diseases.

Sweden

The Swedish healthcare system is organised in seven sections: proximity or closeto- home care (this covers clinics for primary care, maternity care, out-patient mental healthcare, etc.), emergency services, elective care, hospitalisation, out-patient care, specialist treatment and dental care.

The healthcare system is administered by 21 councils, of which 18 are at the county level and three are regional. The population in these 21 areas ranges from 60,000 to 1,900,000. The councils have considerable freedom in planning for the delivery of care and this is one explanation for significant regional variations.

The role of the central government is to establish principles and guidelines for care and to set the political agenda by means of laws and regulations. This is also achieved by means of agreements with the Swedish Association of County Councils and Local Authorities.

At the national level, several expert bodies play a role in planning the healthcare. Social styrelsen (National Board of Health and Welfare) is the central government’s key supervisory authority. The others are Hälso-och sjukvårdens ansvarsnämnd (the Medical Responsibility Board), Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering (Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Healthcare), Läkemedelsförmånsnämnden (the Pharmaceutical Benefits Board), Läkemedelsverket (the Medical Products Agency) and the state-owned Apoteket AB chain of pharmacies.

Hospitals are run by both county and regional authorities. The former include specialised hospitals covering the entire county and general hospitals covering a part of the county.

Medical treatment is provided at both hospitals and outpatient clinics. Specialised treatment is provided by the regional hospital service.

There is a small presence of private (but publicly-financed) healthcare in Sweden, along with political controversy. About one third of medical consultations are with private medical practitioners.

Regulations, waiting times and patient fees vary in the different Councils. The national guarantee of care states that a patient should be able to get an appointment with a primary care physician within five days of contacting the clinic. If referred to a specialist by the GP, they should get an appointment within 30 days, and if treatment is deemed necessary by the specialist, it should be given within 90 days. However, urgent cases are always prioritised and emergent cases are treated immediately.

The main criticism is that waiting times are too long in practice, especially for low priority non emergency surgery such as hip and knee replacement, where the guaranteed time is 90 days.

Nevertheless, Sweden has a far higher rate of efficiency in its healthcare service delivery than most EU members. It has the EU’s highest rate of physicians per capita, at 3.3 per 1,000; although this slightly lags behind non-EU Nordic neighbour Norway, it compares to a rate of two in Britain.Such a ratio allows patients to have quickand easy access to healthcare professionals.

Sweden also recognised in the mid-1990sthat health services had to change to meetincreasing demand, especially as people beganto live longer. As hospital treatmenttends to be expensive compared to GPs oroutpatient/community care, it started topush for more patients to be treated in primarycare. Over the last decade, GP visitshave steadily grown while specialist interventionshave fallen. Sweden has also soughtto drive patients more quickly through thehospital system, a methodology now acknowledgedto be superior (not least interms of reducing nonsocomial infections).

Having less people treated in hospitals,for less time, has allowed Sweden toplough more investment into communityservices, which was one of its goals to beginwith.

Overall, the Swedish State finances the bulk of health care costs (about 95%), with the patient paying a small nominal fee for examination. Hospitalisation charges for patients are capped at SEK 80 per day. Patients under 40 pay only half the cost for the first 30 days of each sickness period.