Researchers at the University of Washington have developed an approach to image functional activity in the brains of individual fetuses, allowing a better look at how functional networks within the brain develop. The research team corrected images for motion, thus allowing a four-dimensional reconstruction of brain activity in moving subjects. The new strategy enables investigations into both normal brain development and the effects of a mother’s diet or environment on the functional development of the fetal brain. The research is funded by the U.S. National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

The research, published online in Human Brain Mapping, examines the naturally developing default mode network in the human fetal brain. Fetal brains are in default mode much of the time, but it is not very well known how this network develops.

The researchers created a four-dimensional movie of fetal default mode network activity using functional MRI. While typically just one measurement is collected for each position at each time point, the team collected multiple measurements, each providing slightly different perspectives. Using the multiple measurements, they were able to reposition the images to create an estimate of what the activation over a period of a few minutes would look like.

After showing they could successfully quantify brain activity in moving subjects by testing the method on adults, the researchers scanned eight fetuses between 32 and 37 weeks of pregnancy, as infants born prematurely at that age have been shown to have active default mode networks. The resulting images were compiled to create a four-dimensional view of each of the brains over a five-minute time window.

“It really hasn’t been explored when these activity networks—these collections of brain areas that start to work together in the brain—emerge and what types of cells and tissues they emerge in,” says Colin Studholme, PhD, a professor with joint appointments in pediatrics and bioengineering at the University of Washington and senior author of the paper. “What this is leading to is not just collecting data from individual babies but also understanding and building a four-dimensional map of brain activity and how it should emerge in a normal baby.”

The technique has potential use in comparing brain development in premature and full-term babies; the effects of alcohol, drug use, or stress during pregnancy; or if there are any prenatal differences in babies that go on to develop neurodevelopmental disorders like autism. Studholme also plans to study the placenta and how its development influences the brain.

The team received support for this study from NIBIB the National Institue of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

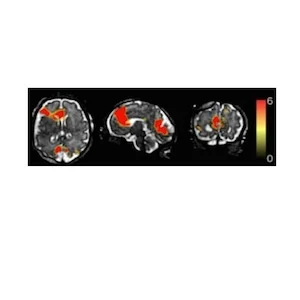

Image caption: Functional MRI of a fetal brain, showing activated regions (red) of the default mode network—a collection of areas that are active when the brain is at rest. Image credit: S. Seshamani et al.

Video credit: Colin Studholme, Biomedical Image Computing Group, University of Washington.

Source: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

The research, published online in Human Brain Mapping, examines the naturally developing default mode network in the human fetal brain. Fetal brains are in default mode much of the time, but it is not very well known how this network develops.

The researchers created a four-dimensional movie of fetal default mode network activity using functional MRI. While typically just one measurement is collected for each position at each time point, the team collected multiple measurements, each providing slightly different perspectives. Using the multiple measurements, they were able to reposition the images to create an estimate of what the activation over a period of a few minutes would look like.

After showing they could successfully quantify brain activity in moving subjects by testing the method on adults, the researchers scanned eight fetuses between 32 and 37 weeks of pregnancy, as infants born prematurely at that age have been shown to have active default mode networks. The resulting images were compiled to create a four-dimensional view of each of the brains over a five-minute time window.

“It really hasn’t been explored when these activity networks—these collections of brain areas that start to work together in the brain—emerge and what types of cells and tissues they emerge in,” says Colin Studholme, PhD, a professor with joint appointments in pediatrics and bioengineering at the University of Washington and senior author of the paper. “What this is leading to is not just collecting data from individual babies but also understanding and building a four-dimensional map of brain activity and how it should emerge in a normal baby.”

The technique has potential use in comparing brain development in premature and full-term babies; the effects of alcohol, drug use, or stress during pregnancy; or if there are any prenatal differences in babies that go on to develop neurodevelopmental disorders like autism. Studholme also plans to study the placenta and how its development influences the brain.

The team received support for this study from NIBIB the National Institue of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Image caption: Functional MRI of a fetal brain, showing activated regions (red) of the default mode network—a collection of areas that are active when the brain is at rest. Image credit: S. Seshamani et al.

Video credit: Colin Studholme, Biomedical Image Computing Group, University of Washington.

Source: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

References:

Seshamani S, Blazejewska AI, Mckown S, Caucutt J, Dighe M, Gatenby C, Studholme C (2016) Detecting default mode networks in utero by integrated 4D fMRI reconstruction and analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016 Nov;37(11):4158-4178. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23303.

Latest Articles

fetal, brain, fetus, MRI, functional MRI

Researchers at the University of Washington have developed an approach to image functional activity in the brains of individual fetuses, allowing a better look at how functional networks within the brain develop. The research team corrected images for mot