I work in a small intensive care

unit (ICU) where we have been writing diaries since 1992. Initially, they were

just little black books with notes by staff and families on how patients were

doing during their ICU stay. In 1999, we began taking photos of the patients to

illustrate their critically ill period, to help them understand and see what

happened. Follow-up teams were introduced in 2012 with guidance from the Swedish

Intensive Care Registry, including health form SF-36.

We visit patients in the ward after ICU discharge to see how they are and offer

them follow-up. The health form used since 2016 is RAND-36

and should be completed two, six and twelve months after discharge. Follow-up

is individual, voluntary and free of charge.

Patients

Patients are often very grateful for

the diary, although it is not unusual for them to just flick through it or even

not look at it at all during the first follow-up visit. Recovery will take time

and follow-up focuses on patients’ needs. It is important to listen to whatever

the patients want to talk about during the visit. The importance of the diaries

is demonstrated when patients have vivid memories and the diaries are able to

provide explanations. For example, a patient remembers his throat being cut

with a knife; the diary tells the patient he had a central venous catheter put

in and we can then explain the procedure to him. Patients have such

wide-ranging comments. It is often a relief for them to tell us stories their

relatives don’t believe and sometimes we can help them find some kind of

reality in the story or just reassure them that it can be like that after ICU.

For some patients, their entire stay is a blank, so for them the diary is a

precious tool. There are also patients who decline follow-up. They usually say

they don’t need it, but it is possible that they are suffering in silence, we

don’t always know.

Families

We encourage patients’ families and

friends to write in the diaries. They can write about anything, such as their

own feelings, their hope that the patient will recover, the weather outside or

something funny grandchildren did or said. Those small stories can help fill

the gap of time that patients can lose during illness. It is also valuable to

families of the critically ill whose world has been turned upside down. The

diaries become a chronological record of what happened during the stay.

Families are often eager to tell stories and share memories from ICU stays. Studies show that relatives can also suffer post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following ICU stays. Where possible, we try to show relatives and patients the actual place where patients spent most of their time at ICU. It is often more emotional for relatives than patients because of the memories it brings up.

As for staff, we try to write brief

details on a daily basis, including progress in conditions and training with

the physiotherapist. We also note any difficulties and whether patients’

conditions are deteriorating in any way.

The Physiotherapist

The physiotherapist sees the

patients every week day during their stay, and patients clearly remember her

for literally putting them back on their feet. At the follow-up, various tests

are carried out to monitor progress. Patients are often keen for tangible

evidence of their progress during recovery, in addition to new goals and

training schedules.

In conclusion, the diary is a very important resource to both patients and families. It can help patients recover lost time and increase their understanding of what happened to them during a period of critical illness.

Here are some photos from one of our diaries. It´s straightforward to use and is currently being updated. We also include a leaflet for relatives to describe what the patient likes to do when he or she is healthy, like sport, music, sleeping patterns (early bird or night owl). Things relatives would like us to know or what they think the patient would want us to know.

Diary cover |  Inside the diary, for writing and photos |

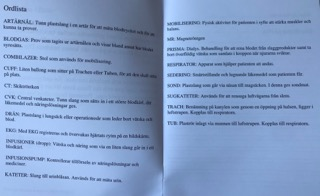

A glossary of words used in the ICU