ICU Management & Practice, Volume 25 - Issue 3, 2025

Music therapy’s (MT) integration into the ICU liberation bundle is underexplored. We highlight existing literature, present vignettes illustrating MT in action, and offer recommendations to optimise ICU MT across the lifespan.

Introduction

The Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Liberation Bundle (A-F) is a comprehensive set of evidence-based guidelines developed by the Society of Critical Care Medicine focused on assessment, prevention and management of physical, psychological and cognitive symptoms commonly experienced by critically ill patients across the lifespan (Society of Critical Care Medicine 2025). Each item of the bundle corresponds to a specific aspect of care management, with effective implementation requiring strong interdisciplinary collaboration and adaptation of interventions to meet individual patient needs (Dodds et al. 2023). Daily application of the ICU liberation bundle aims to improve survival, reduce delirium and prolonged mechanical ventilation, decrease length of stay and ICU readmission, and mitigate long-term impacts of hospitalisation (Barr et al. 2024; Ely 2017; Pun et al. 2020; Pun et al. 2019).

Music therapy (MT) is a potentially impactful but underutilised rehabilitation discipline in the ICU. MT is the clinical, evidence-based and holistic use of music in relationship with a trained music therapist (MT-BC) to address individualised healthcare goals. In the United States, music therapists complete a multi-year training process (minimum bachelor’s degree and clinical internship) and hold a national certification and state licensure (when applicable) to practice music therapy (American Music Therapy Association 2025). Available literature demonstrates the potential impact of MT on vital signs, anxiety, and pain in the ICU, primarily through the use of rhythmic entrainment (Thaut et al. 2015). MT has been utilised to promote physiologic stability, with significant reductions in heart rate noted for paediatric (Bush et al. 2021) and adult (Golino et al. 2023) patients receiving mechanical ventilation. MT may also reduce self-reported pain and anxiety in critically ill adults (Chahal et al. 2021; Golino et al. 2019) and improve COMFORT behaviour scale scores in critically ill children (Ferro et al. 2023).

Though Modrykamien (2023) proposed that MT may enhance the ICU liberation bundle given its current aims and uses, MT’s comprehensive integration has yet to be fully explored. A focus on MT is timely, given the increased emphasis on developing non-pharmacologic interventions to prevent ICU-induced sequelae that may develop into Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS) for patients and families (PICS-F) (Geense et al. 2019). It is imperative that paediatric and adult clinicians understand MT and its potential benefits to support timely clinical referrals and maximise access to the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial supports available through engagement in MT.

This article illustrates how MT integration may be optimised to support all six elements of the ICU liberation bundle, articulated through the lens of our team’s real-world experiences implementing a new MT programme at Johns Hopkins Hospital across the age spectrum. Our team is comprised of two MT-BCs working in adult (author 1) and paediatric (author 2) critical care, an adult critical care physician (author 3), and a paediatric critical care physician and anaesthesiologist (author 4).

For each bundle element, a short summary of related MT literature is provided alongside alternating paediatric (age 6) and adult (age 40) composite case vignettes depicting MT in action at two points across the lifespan for a patient with the same diagnoses and clinical needs. Within each vignette, interdisciplinary collaboration, patient preferences, and flexible use of music to support clinical outcomes are emphasised. While the case vignettes draw heavily on our team’s experiences of practicing in the ICU, they are fictionalised to protect confidentiality and highlight the changing role of MT for patients of different ages.

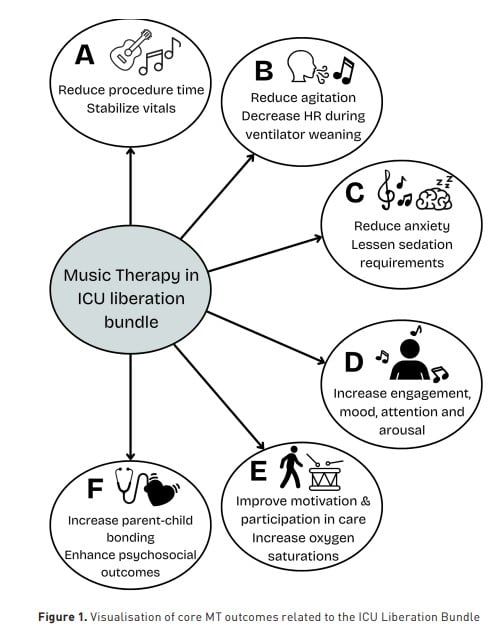

Figure 1 offers an overarching summary of core MT outcomes discussed in relation to ICU liberation bundle elements.

Introducing Isaiah: Clinical Background

Isaiah is a 6-year-old boy/40-year-old gentleman with a history of mild intermittent asthma. He presents with five days of fever, cough, and worsening shortness of breath. On exam, he is hypoxaemic with an oxygen saturation of 82% on room air and in visible respiratory distress with tachypnoea and accessory muscle use. A respiratory viral panel is positive for influenza A, and a chest x-ray shows bilateral infiltrates. He is intubated and admitted to the paediatric/medical intensive care unit for management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to influenza pneumonia. After two weeks on the ventilator, he is unable to be extubated due to hypoxaemia and agitation and undergoes tracheostomy.

A: Assess, prevent and manage pain

In adult critical care, MT is recommended as a nonpharmacologic intervention for pain in the ICU Liberation Bundle under the “A” element (Society of Critical Care Medicine 2021). Golino et al. (2019) found that a single MT session improved self-reported pain by 1.2 points and anxiety by 2.7 points in critically ill adults while simultaneously reducing heart rate and respiration rate. When MT was delivered to patients receiving palliative care, including ICU-based consults, MT decreased pain scores measured via the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability scale (FLACC) and Functional Pain Scale (FPS) (Gutgsell et al. 2013). Music therapist-led music listening and music-assisted relaxation has also been shown to decrease pain and anxiety in critically ill burn patients (Cordoba-Silva et al. 2024) and patients with polytrauma on a resuscitation unit (Contreras-Molina 2021). MT’s impact on pain has been underexplored in paediatric critical care, but initial findings demonstrate improved vital signs and decreased behavioural pain ratings following live MT (Ferro et al. 2023; Kobus et al. 2022b).

MT may also reduce pain perception associated with bedside procedures performed in the ICU. Adult ICU patients have described the calming impact of live MT during procedures ranging from endotracheal tube removal (ETT), tracheostomy replacement, and routine nursing care, framing participation in MT as a strategy to improve pain perception (Saldaña-Ortiz et al. 2025b). Live MT delivered during peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement for paediatric oncology patients resulted in shorter placement time, reduced use of sedatives, and reduced pain perception (Zhang et al. 2023). Further, MT-supported paediatric procedures including bedside sclerotherapy (Tulin-Silver et al. 2023), intravenous placement (Ortiz et al. 2019), and immunisations (Yinger 2016) also improved coping and reduced parental perceptions of their child’s distress.

Case Vignette: Managing Isaiah’s Pain (paediatric)

The MT-BC (JS) visited Isaiah on the second day of his admission following a nursing referral for uncontrolled pain. When the MT-BC arrived, Isaiah was intubated with a FLACC score of 6 (grimacing, arched back, crying). The MT-BC began by introducing MT to his parents. When asked about music preferences, they shared that Isaiah loves to sing and dance, specifically to the songs “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star”, “We Are the Dinosaurs” (Laurie Berkner), and “Wheels on the Bus”. The MT-BC invited Isaiah’s parents to join her at the bedside, saying, “Hi Isaiah! My name is Jamie, and I play music with kids in the hospital to help them feel better. I can see that you're hurting a lot. Is that right?" Isaiah turned his head and nodded tearfully. The MT-BC explained that she heard he loves the song “We are the Dinosaurs,” and asked if he would like to hear some music. Isaiah nodded again and reached out toward his mother.

The MT-BC noted Isaiah’s high heart rate (HR), high respiration rate (RR), and work of breathing, then began to play “We are the Dinosaurs” on the guitar at a tempo that closely matched his heart rate (~130bpm). As the song continued, the MT-BC gradually decreased the tempo of the song while transitioning into another preferred song (Twinkle Twinkle Little Star) in the same key. After 20 minutes of music entrainment, during which the MT-BC played songs continuously while gradually decreasing the tempo, Isaiah closed his eyes and fell asleep. Isaiah’s HR had returned to baseline (~85bpm), and he was no longer grimacing.

B: Both spontaneous awakening trials and spontaneous breathing trials

An emerging area of MT practice in ICU settings emphasises MT’s role for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. In adult critical care, findings are conflicting. Golino et al. (2023) found that live receptive MT that was synchronised with vital signs to stimulate a relaxation response reduced agitation and heart rate in vented patients. In contrast, Ettenberger et al. (2024) found trendstoward decreasing heart rate and respiration rate but no significant differences in anxiety for vented patients who received MT. Other teams have engaged a MT-BC in the design of patient-directed recorded music listening experiences, which lowered anxiety measured via the 100-mm Visual Analog Scale Anxiety (VAS-A) in ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation (Chlan et al. 2013). In paediatric patients receiving mechanical ventilation, live MT produced significant reductions in heart rate immediately and 60 minutes following MT (Bush et al. 2021).

Evidence for implementation of MT during spontaneous breathing trials is limited, particularly in terms of sedation holidays and/or spontaneous breathing trials on pressure support. MT has, however, been preliminarily explored during ventilator weaning. Hunter et al. (2010) began MT sessions 20 minutes prior to tracheostomy collar switch and 40 minutes into weaning trials, with results demonstrating decreased heart rate and respiration rate, increased relaxation, and high patient and staff acceptability. A recent study protocol for MT during weaning from mechanical ventilation in the ICU plans to explore the impact of MT on sedatives and analgesia, agitation, delirium, pain perception, and vital signs (Pereiro Martinez et al. 2024).

Case Vignette: Isaiah’s Tracheostomy Collar Trial (adult)

Following Isaiah’s tracheostomy, MT was consulted for support during his first spontaneous breathing trial. The MT-BC (KD) coordinated scheduling with the respiratory therapist (RT) and arrived before the trial began to build rapport with Isaiah, who communicated using gestures (e.g., thumbs up/down) and written phrases. When asked about music preferences, Isaiah sat up excitedly and wrote “Green Day”, “Blink 182”, and “Foo Fighters”, which he underlined for emphasis. The MT-BC proposed they make a set list for his tracheostomy collar (TC) trial and wrote song titles in the order Isaiah selected them in the corner of his dry-erase board. The MT-BC began playing and singing “Anthem, Part Two” (Blink 182) on the guitar, during which Isaiah was observed mouthing lyrics, bobbing his head to the beat, and approximating a "rock on" gesture with his right hand.

The RT arrived during this song and initiated the ventilator to TC switch. Isaiah appeared to panic and rapidly developed tachypnoea. The MT-BC prompted Isaiah to re-focus on the music, beginning to play power chords from “Everlong” (Foo Fighters) in a tempo aligned with his respiration rate. Isaiah’s eyes widened in recognition as the MT-BC began to sing relevant lyrics to further regulate the tempo of his breathing (e.g.,“Breathe out/So I can breathe you in/Everlong”). Across a 10-minute period, the MT-BC gradually slowed the tempo of the song as Isaiah’s respiration rate decreased, allowing the TC trial to continue without additional PRN delivery. The MT-BC remained for 30 minutes of Isaiah’s TC trial, concluding MT when he appeared calm and the RT and nursing staff expressed satisfaction with his vital signs.

C: Choice of analgesia and sedation

Less is known about the impact of MT on analgesia and sedation for critically ill patients. Chlan et al. (2018) found that their MT-BC designed, patient-directed recorded music listening intervention for adult ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation saved approximately $2,000 USD per patient due to better managed anxiety and lessened sedation requirements. A retrospective review of charts of hospitalised adult patients also demonstrated that MT sessions reduced verbal anxiety scores by an average of 2.93 points (Brown et al. 2024). Though music/MT were recommended to augment analgesia in the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s clinical practice guidelines for Pain, Agitation, Neuromuscular Blockade, and Delirium in critically ill paediatric patients with considerations of the ICU Environment and Early Mobility (PANDEM) (Smith et al. 2022), findings differ with respect to sedation levels. Guerra et al. (2021) MUSiCC pilot revealed that music therapist-selected recordings did not impact daily sedation intensity scores for paediatric ICU (PICU) patients.

Two study protocols plan to explore the relationship between MT and pain medication usage for adult burn patients in the ICU (Ettenberger et al. 2021) and MT-supported personalised and generalised music listening to reduce neuroactive drug needs in adult ICU patients (Mistraletti et al. 2024).

Case Vignette: Avoiding additional sedation (paediatric)

Immediately following the MT entrainment session to support Isaiah’s pain management, Isaiah’s nurse re-entered the room to assess the need for additional analgesic medication. After assessing Isaiah's FLACC pain score to be 1 (no grimacing; calm and restful state), Isaiah’s nurse asked the MT-BC (JS) what contributed most to the decrease in his pain and discomfort. The MT-BC explained that she had engaged Isaiah in a passive music experience during which he listened to preferred live music while the music decreased in tempo along with his heart rate. Music entrainment appeared to reduce his anxiety, discomfort, agitation, and pain. Isaiah’s parents shared their relief that Isaiah began to calm down immediately once the MT-BC began to play a preferred song. Because of the MT intervention, no additional sedation was required.

D: Delirium: Assess, prevent and manage

Music therapists have been involved in the design and delivery of live and recorded music interventions to prevent delirium in specific groups of critically ill patients, though recorded music listening is more commonly utilised (Golubovic et al. 2022). Cheong et al. (2016) found that active MT involving improvisation and familiar songs increased engagement, mood, and alertness in hospitalised older adults with delirium and dementia. Future feasibility trials are planned to explore the impact of live and recorded music interventions in acute geriatric patients with delirium (Golubovic et al. 2023; Seyffert et al. 2022), with preprint pilot data demonstrating significant improvements in attention (Golubovic et al. 2025). In contrast, Crew et al. (2025) found that their live MT and music listening protocol did not reduce delirium for mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU.

Other teams have utilised recorded music with (Head et al. 2022) and without (Khan et al. 2020) MT-BCs present for intervention delivery. Head et al. (2022) positive stimulation protocol for medically sedated adult patients involved recordings of stories told by family members paired with patient-preferred music, with MT-BCs monitoring for agitation and arousal. Khan et al. (2020) note that MT-BCs selected the music but were not consulted daily in their feasibility pilot on music listening for delirium in the adult ICU. Music therapist-selected classical music did not reduce delirium in critically ill children receiving mechanical ventilation but was found to have high acceptability while raising important questions about the impact of future parental engagement in music selection to optimise salience (Garcia Guerra et al. 2021). Dai et al. (2025) highlight low certainty of available evidence but suggest an optimal dose of recorded music for adults with delirium as 2–30-minute listening sessions a day for 7 days.

Case Vignette: Mitigating Isaiah’s delirium (adult)

Isaiah experienced an acute change in mental status and attempted to remove his endotracheal tube early in his ICU stay, requiring restraints for his safety. He scored +3 on the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) and scored positive for delirium on the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM-ICU) assessment. MT was offered when Isaiah’s wife Gabi was at bedside to maximise orientation and empower family engagement. When the MT-BC (KD) arrived, Isaiah was displaying frequent non-purposeful movement that Gabi found distressing. She said, “It looks like he’s trying to escape. I hate seeing his hands tied down.” The MT-BC engaged Gabi in therapeutic conversation, sharing information about delirium while simultaneously affirming Gabi’s lived experiences. Gabi told the music therapist that she had been playing Isaiah’s favourite rock albums prior to his change in mental status but now felt nervous about playing music, talking to, or touching Isaiah because he looked uncomfortable.

The MT-BC invited Gabi to move her chair closer to Isaiah’s bed and positioned herself on the other side with a clear line of sight to the monitor. She re-introduced herself to Isaiah, took his hand, and began tapping a steady, rhythmic beat while humming the chorus from “When I Come Around” (Green Day), a song that Gabi identified as personally salient. Gabi began humming along to the chorus, which was altered to include Isaiah’s name (“No time to search the world around/Cause you know where he’ll be found/When Isaiah comes around”). With encouragement and the addition of supportive guitar play, Gabi sang the chorus alone while holding Isaiah’s other hand. As Gabi continued to sing, Isaiah’s body noticeably calmed, and he was observed opening his eyes and fixing his gaze on her for brief periods of time before appearing to fall asleep.

As Isaiah slept, Gabi expressed gratitude for the opportunity to play an active role in helping Isaiah relax. The MT-BC suggested that moving forward, they work together to create a playlist of recorded songs that Gabi could take the lead in playing for Isaiah twice a day and/or when the MT-BC is not on unit.

E: Early mobility and exercise

While integration of MT into early mobilisation practices has been minimally explored, MT has been utilised to support motor and rehabilitation goals in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Many have explored the impact of rhythmic cueing on gait and upper extremity functioning in adults with movement disorders (Koshimori et al. 2024; Devlin et al. 2019), stroke (Palumbo et al. 2024), and those receiving care in inpatient rehabilitation settings (Edwards and Jayabalen 2023; Mercier et al. 2023), citing potentials for functional motor improvements in tandem with improvements in mood and engagement (Street et al. 2020; Mercier et al. 2023).

In paediatric medical settings, MT-BCs have co-treated with rehabilitation therapies to maximise physiological stability. In hospitalised children with neurologic diseases, live MT and physical therapy (PT) co-treatment lowered heart rate and respiration rates while increasing oxygen saturation compared to PT alone (Kobus et al. 2022a). Additionally, infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) who received music therapy and occupational therapy (OT) co-treatment sessions demonstrated a significant decrease in pre/post-session FLACC scores and increased oxygen saturations versus standard care OT (Brinkley et al. 2024). More broadly, MT has been used as a motivator to promote adherence to rehabilitative interventions (Burns et al. 2025).

Since the integration of a full-time MT-BC to our PICU in 2023, our team reports anecdotal benefit from their inclusion in monthly interdisciplinary meetings of our PICU Up! ICU Liberation Program. The PICU-Up! programme includes levels and tiered activity plans aimed at increasing early mobilisation activities in critically ill paediatric patients through collaborative engagement of key PICU staff, including but not limited to physicians, nursing, rehabilitation therapies, respiratory therapy, child life, and now, music therapy (Wieczorek et al. 2016). The opportunity for our MT-BC to interface with other rehabilitation professionals and engage in developing early mobilisation initiatives has increased the frequency of MT and PT and/or OT co-treatment sessions in our PICU.

Case Vignette: Mobilising Isaiah (paediatric)

Isaiah’s team identified readiness for mobilisation and exercise during PICU Up! rounds following extubation. An OT was consulted to assess Isaiah’s activity capacity, neurologic status, and physical strength. Isaiah’s OT contacted the MT-BC after observing his love for music and dancing during their initial assessment. The OT noted that Isaiah was not able to grasp a spoon and bring it to his mouth, but when presented with a small maraca, gripped it tightly and shook it while smiling. The MT-BC and OT met before co-treatment to discuss how music could support Isaiah’s physical rehabilitation goals of 1) increasing muscle tone and flexibility, 2) increasing endurance, and 3) increasing pelvic and lower extremity strength for weight bearing.

When the MT-BC and OT arrived, Isaiah was slumped over in bed, watching television with his father. Isaiah initially declined, loudly stating, “NO. I want to watch BLUEY”. However, when presented with a lollipop drum used in a previous MT session, Isaiah turned away from the TV and reached out for the drum. The MT-BC invited Isaiah to explore the drum while following along on the guitar (e.g., playing faster/slower). Noticing that Isaiah was using his right arm to strike the drum, Isaiah’s OT took hold of the drum handle. They strategically positioned the drum to encourage stretching, reaching, and mobility by holding the lollipop drum above Isaiah’s head, encouraging him to reach his right arm higher in order to strike it, then moving the lollipop drum below his torso, encouraging him to stretch his right arm down to strike it. Throughout, the MT-BC provided a steady beat while singing, "Tap to the beat/tap up high/tap down low”. Throughout this game, Isaiah was observed smiling, laughing, singing, and hitting the drum with 100% accuracy in each field.

Isaiah then stood at the edge of his bed with support from the OT, who coached Isaiah’s father to re-position the lollipop drum near Isaiah's feet. The MT-BC began playing "Wheels on the Bus” with altered lyrics (e.g., "Our feet on the drum go kick, kick, kick”), during which Isaiah was prompted to lift each leg in isolation to kick the drum. When the MT-BC and OT prepared to leave, Isaiah exclaimed, “That was fun! I want to keep going. Another song!”

F: Family engagement and empowerment

MT is well-positioned to support the psychosocial needs of patients andtheir care partners in settings including the paediatric and adult ICU, the NICU, hospice and palliative care, and oncology (Steiner-Brett 2023). Family members of critically ill adult patients highlight how MT humanises the ICU environment, improves relationships between family members and the healthcare team, and responds directly to family member needs (Saldaña-Ortiz et al. 2025a). Parents of PICU patients who received MT also believe MT promotes improved communication with the PICU team while simultaneously supporting their child’s well-being (Cousin et al. 2022). In the NICU, MT has been deployed to promote parent-infant bonding with the added benefit of more fully engaging parents as partners in their infant’s care (Ormston et al. 2022; Bansal et al. 2024; Ghetti et al. 2023a; Haslbeck and Hugoson 2017; Corrigan et al. 2022; Ettenberger and Ardilla 2018).

Stakeholders indicate that MT may be associated with immediate benefits in palliative care and end-of-life contexts, citing its ability to jointly enhance psychological, spiritual, physical, emotional, and social outcomes for patients and care partners pre- and post-loss (Burns et al. 2025; Gallagher et al. 2017; Gillespie et al. 2024; Kammin et al. 2024; Magill 2009). Engaging family members in process-oriented music-based legacy projects like heartbeat songs, which embed the recorded heartbeat of a patient as the drumbeat of a family-selected song, offers unique meaning-making opportunities that facilitate grief expression and coping (Ghetti et al. 2023b; Schreck et al. 2022; Walden et al. 2021).

Case Vignette: Supporting Isaiah’s family (adult)

MT sessions played a pivotal role in offering psychosocial support to Isaiah’s family throughout his hospitalisation. While Isaiah was not conscious during his first MT session, his wife Gabi offered essential information about his music preferences. Gabi shared that she, Isaiah, and their 8-year-old child Micah loved going to rock concerts together and showed the MT-BC (KD) videos from a Black Keys concert they attended. When not addressing Isaiah’s emergent clinical needs like delirium and ventilator weaning, MT sessions offered Gabi a space to process Isaiah’s hospitalisation and reconnect with him through the music they both love.

In each session, Gabi (and Isaiah, when able) chose songs for the MT-BC to play live, which facilitated opportunities for reminiscence, bonding, and song lyric discussion. For example, the song “Times Like These” (Foo Fighters) provided an important moment of emotional release for Gabi, who reflected on nuanced feelings of pressure given her role as Isaiah’s sole healthcare decision-maker coupled with deep feelings of gratitude for the ways in which this experience has strengthened her family system and faith.

When Isaiah’s delirium was more effectively managed, Gabi wondered if Micah should visit, though she worried they would fear the tubes and lines keeping Isaiah alive. The MT-BC worked with Gabi, the unit social worker, and a child life specialist to prepare Micah to come to the ICU. MT was planned during the first part of Micah’s visit as a way to humanise the environment through shared engagement in familiar, meaningful songs pre-selected by Gabi, Isaiah and Micah. During MT, Micah curled up on Isaiah’s bed and requested to hear “Everlasting Light” (The Black Keys), a song that Isaiah and Gabi had used as a lullaby throughout Micah’s childhood. The MT-BC repeated a particularly salient lyric from the song (“Loneliness is over/The dark days are through”) as Gabi, Micah, and Isaiah held each other while tearfully singing together.

Conclusion

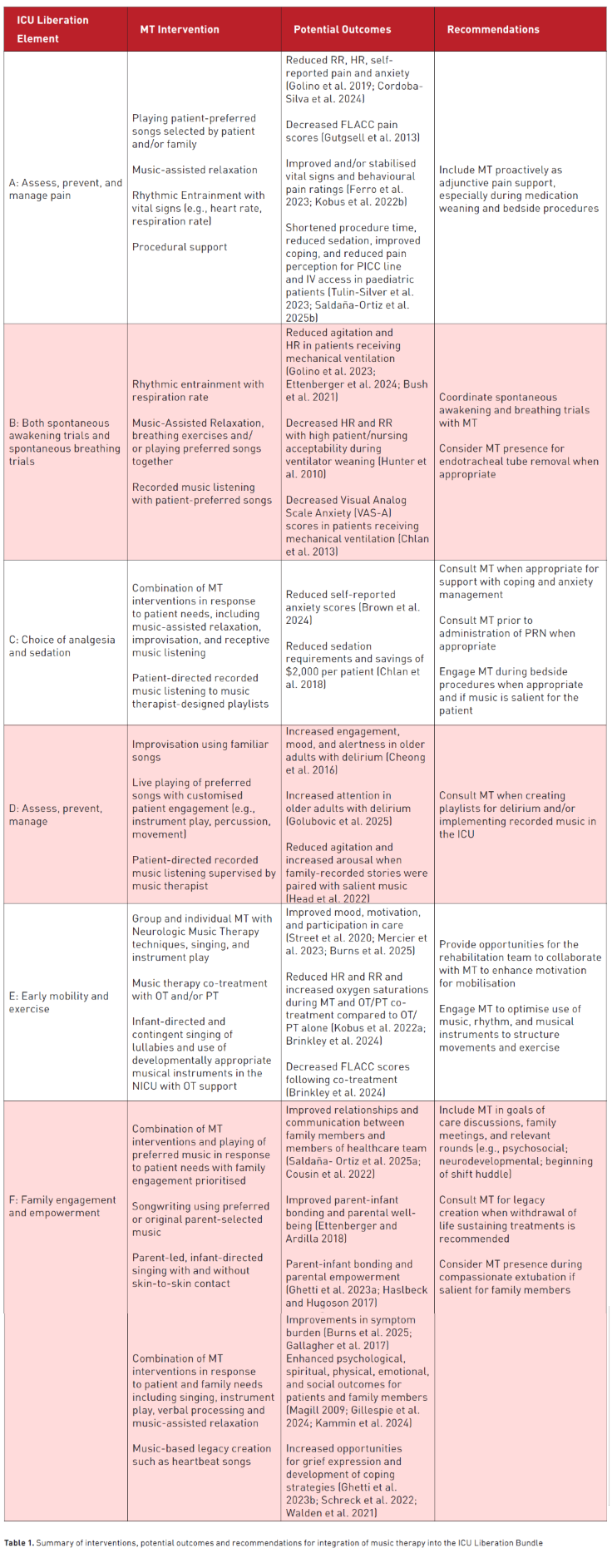

In the above vignettes, we illustrate how MT can be utilised to address the six core elements of the ICU liberation bundle for patients across the age spectrum. Table 1 summarises MT interventions and potential outcomes summarised in this article, as well as recommendations for critical care teams seeking to optimise MT’s integration into the ICU liberation bundle.

MT’s anxiolytic and physiologic effects have been documented with increasing frequency. However, more research is needed to uncover the specific role(s) and benefits of MT across various aspects of ICU liberation and critical care – particularly with regards to spontaneous breathing and awakening trials, delirium, sedation, and early mobilisation. In general, more MT literature was available in adult critical care, highlighting the urgent need for prospective MT research undertaken in paediatric critical care.

At a practical level, we invite hospitals to prioritise funding for the development of robust MT programming in ICU settings and beyond. Music therapists offer unique perspectives on patient care, ultimately enriching interdisciplinary collaboration through their engagement in medical rounds, goals of care discussions, and service delivery. There is potential for music therapist involvement at each level of the ICU liberation bundle, especially for patients and/or family members for whom music is salient. As in the fictionalised case of Isaiah, MT can address emergent clinical needs, such as pain, delirium, and ventilator weaning, while providing consistent, long-term psychosocial support.

More broadly, we urge medical providers to conceptualise music therapy not as a “nice to have” extra, but rather, as a new standard of care (Knott et al. 2022). The inclusion of MT in the ICU liberation bundle provides expanded opportunities to proactively engage patients and families in individualised, sensory-rich interventions aimed at mitigating ICU-induced sequalae (Inoue et al. 2024; Shirasaki et al. 2024). As such, integrating MT into the ICU milieu communicates a desire to care for patients and their families in ways that honour their medical andpsychosocial needs in tandem.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

American Music Therapy Association (AMTA). What you need to be a music therapist. Silver Spring (MD): American Music Therapy Association; 2021. Available from: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/requirements/

Bansal S, Molloy EJ, Rogers E, Bidegain M, Pilon B, Hurley T, Lemmon ME. Families as partners in neonatal neuro-critical care programs. Pediatr Res. 2024;96(4):912–21.

Barr J, Downs B, Ferrell K, Talebian M, Robinson S, Kolodisner L, Kendall H, Holdych J. Improving outcomes in mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients following implementation of the ICU liberation (ABCDEF) bundle across a large healthcare system. Crit Care Explor. 2024;6(1):e1001.

Brinkley M, Biard M, Masuoka I, Hagan J. Evaluation of occupational therapy and music therapy co-treatment in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2024;44(4):513–25.

Brown CS, Patmon F, Freilich J, Heiderscheit A. Reduction of anxiety through music therapy during hospitalization: a retrospective study. Music Ther Perspect. 2024;42(1):83–9.

Burns J, Healy H, O’Connor R, Moss H. Integrative review of music and music therapy interventions on functional outcomes in children with acquired brain injury. J Music Ther. 2025;62(1):thae017.

Bush HI, LaGasse AB, Collier EH, Gettis MA, Walson K. Effect of live versus recorded music on children receiving mechanical ventilation and sedation. Am J Crit Care. 2021;30(5):343–9.

Cheong CY, Tan JAQ, Foong YL, Koh HM, Chen DZY, Tan JJC, Ng CJ, Yap P. Creative music therapy in an acute care setting for older patients with delirium and dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2016;6(2):268–75.

Chlan LL, Weinert CR, Heiderscheit A, Tracy MF, Skaar DJ, Guttormson JL, Savik K. Effects of patient-directed music intervention on anxiety and sedative exposure in critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilatory support: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2335–44.

Chlan LL, Heiderscheit A, Skaar DJ, Neidecker MV. Economic evaluation of a patient-directed music intervention for ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilatory support. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1430–5.

Contreras-Molina M, Rueda-Núñez A, Pérez-Collado ML, García-Maestro A. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and pain in the critical polytraumatised patient. Enferm Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021;32(2):79–87.

Cordoba-Silva J, Maya R, Valderrama M, Giraldo LF, Betancourt-Zapata W, Salgado-Vasco A, Marín-Sánchez J, Gómez-Ortega V, Ettenberger M. Music therapy with adult burn patients in the intensive care unit: short-term analysis of electrophysiological signals during music-assisted relaxation. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23592.

Corrigan M, Keeler J, Miller H, Naylor C, Diaz A. Music therapy and family-integrated care in the NICU: using heartbeat-music interventions to promote mother–infant bonding. Adv Neonatal Care. 2022;22(5):e159–68.

Cousin VL, Colau H, Barcos-Munoz F, Rimensberger PC, Polito A. Parents’ views with music therapy in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: a retrospective cohort study. Children (Basel). 2022;9(7):958.

Crew J, Abdelmonem A, Wang X, Harmon C Jr, Modrykamien A. Music therapy in addition to music listening for the prevention of delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2025;38(3):285–90.

Dai RS, Wang TH, Chien SY, Tzeng YL. Dose–response analysis of music intervention for improving delirium in intensive care unit patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Crit Care. 2025:1–14.

Devlin K, Alshaikh JT, Pantelyat A. Music therapy and music-based interventions for movement disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19(11):83.

Dodds E, Kudchadkar SR, Choong K, Manning JC. A realist review of the effective implementation of the ICU Liberation Bundle in the paediatric intensive care unit setting. Aust Crit Care. 2023;36(5):837–46.

Edwards ER, Jayabalan P. Soothe the savage beast: patient perceptions of the benefits of music therapy in an inpatient rehabilitation facility. PM R. 2023;15(9):1092–7.

Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):321–30.

Ettenberger M, Beltrán Ardila YM. Music therapy song writing with mothers of preterm babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) – a mixed-methods pilot study. Arts Psychother. 2018;58:42–52.

Ettenberger M, Maya R, Salgado-Vasco A, Monsalve-Duarte S, Betancourt-Zapata W, Suarez-Cañon N, Prieto-Garces S, Marín-Sánchez J, Gómez-Ortega V, Valderrama M. The effect of music therapy on perceived pain, mental health, vital signs, and medication usage of burn patients hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit: a randomized controlled feasibility study protocol. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:714209.

Ettenberger M, Casanova-Libreros R, Chávez-Chávez J, Cordoba-Silva JG, Betancourt-Zapata W, Maya R, Fandiño-Vergara LA, Valderrama M, Silva-Fajardo I, Hernández-Zambrano SM. Effect of music therapy on short-term psychological and physiological outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients: a randomized clinical pilot study. J Intensive Med. 2024;4(4):515–25.

Ferro MM, Pegueroles AF, Lorenzo RF, Roy MÁ, Forner OR, Jurado CME, Julià NB, Benito CG, Hernández RH, Alcaraz AB. The effect of a live music therapy intervention on critically ill paediatric patients in the intensive care unit: A quasi-experimental pretest–posttest study. Aust Crit Care. 2023;36(6):967–973.

Gallagher LM, Lagman R, Bates D, Edsall M, Eden P, Janaitis J, Rybicki L. Perceptions of family members of palliative medicine and hospice patients who experienced music therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(6):1769–1778.

Garcia Guerra G, Joffe AR, Sheppard C, Hewson K, Dinu IA, Hajihosseini M, deCaen A, Jou H, Hartling L, Vohra S; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Music use for sedation in critically ill children (MUSiCC trial): A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Intensive Care. 2021;9(1):7.

Geense WW, van den Boogaard M, van der Hoeven JG, Vermeulen H, Hannink G, Zegers M. Nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse long-term outcomes among ICU survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(11):1607–1618.

Ghetti CM, Gaden TS, Bieleninik Ł, Kvestad I, Assmus J, Stordal AS, Aristizabal Sanchez LF, Arnon S, Dulsrud J, Elefant C, Epstein S, Ettenberger M, Glosli H, Konieczna-Nowak L, Lichtensztejn M, Lindvall MW, Mangersnes J, Murcia Fernández LD, Røed CJ, Gold C. Effect of music therapy on parent-infant bonding among infants born preterm: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023a;6(5):e2315750.

Ghetti CM, Schreck B, Bennett J. Heartbeat recordings in music therapy bereavement care following suicide: Action research single case study of amplified cardiopulmonary recordings for continuity of care. Action Res. 2023b;22(4):362–380.

Gillespie K, McConnell T, Roulston A, Potvin N, Ghiglieri C, Gadde I, Anderson M, Kirkwood J, Thomas D, Roche L, O’Sullivan M, McCullagh A, Graham-Wisener L. Music therapy for supporting informal carers of adults with life-threatening illness pre- and post-bereavement; a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23(1):55.

Golino AJ, Leone R, Gollenberg A, Christopher C, Stanger D, Davis TM, Meadows A, Zhang Z, Friesen MA. Impact of an active music therapy intervention on intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2019;28(1):48–55.

Golino AJ, Leone R, Gollenberg A, Gillam A, Toone K, Samahon Y, Davis TM, Stanger D, Friesen MA, Meadows A. Receptive music therapy for patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2023;32(2):109–115.

Golubovic J, Neerland BE, Aune D, Baker FA. Music interventions and delirium in adults: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 2022;12(5):568.

Golubovic J, Baker FA, Simpson MR, Neerland BE. Live and recorded music interventions for management of delirium symptoms in acute geriatric patients: Protocol for a randomized feasibility trial. Nord J Music Ther. 2023;33(1):62–83.

Golubovic J, Neerland BE, Simpson MR, Johansson K, Baker FA. A randomized pilot and feasibility trial of live and recorded music interventions for management of delirium symptoms in acute geriatric patients. BMC Geriatr. 2025;25(1):306.

Gutgsell KJ, Schluchter M, Margevicius S, DeGolia PA, McLaughlin B, Harris M, Mecklenburg J, Wiencek C. Music therapy reduces pain in palliative care patients: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(5):822–831.

Haslbeck F, Hugoson P. Sounding together: Family-centered music therapy as facilitator for parental singing during skin-to-skin contact. In: Filippa M, Kuhn P, Westrup B, editors. Early vocal contact and preterm infant brain development: Bridging the gaps between research and practice. Cham (CH): Springer Int Pub; 2017. p. 217–238.

Head J, Gray V, Masud F, Townsend J. Positive stimulation for medically sedated patients: A music therapy intervention to treat sedation-related delirium in critical care. Chest. 2022;162(2):367–374.

Hunter BC, Oliva R, Sahler OJZ, Gaisser D, Salipante DM, Arezina CH. Music therapy as an adjunctive treatment in the management of stress for patients being weaned from mechanical ventilation. J Music Ther. 2010;47(3):198–219.

ICU Liberation Bundle (A-F). Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). 2018. Available from: https://sccm.org/clinical-resources/iculiberation-home/abcdef-bundles

Inoue S, Nakanishi N, Amaya F, Fujinami Y, Hatakeyama J, Hifumi T, Iida Y, Kawakami D, Kawai Y, Kondo Y, Liu K, Nakamura K, Nishida T, Sumita H, Taito S, Takaki S, Tsuboi N, Unoki T, Yoshino Y, Nishida O. Post-intensive care syndrome: Recent advances and future directions. Acute Med Surg. 2024;11(1):e929.

Kammin V, Fraser L, Flemming K, Hackett J. Experiences of music therapy in paediatric palliative care from multiple stakeholder perspectives: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Palliat Med. 2024;38(3):364–378.

Khan SH, Xu C, Purpura R, Durrani S, Lindroth H, Wang S, Gao S, Heiderscheit A, Chlan L, Boustani M, Khan BA. Decreasing delirium through music: A randomized pilot trial. Am J Crit Care. 2020;29(2):e31–e38.

Knott D, Krater C, MacLean J, Robertson K, Stegenga K, Robb SL. Music therapy for children with oncology & hematological conditions and their families: Advancing the standards of psychosocial care. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Nurs. 2022;39(1):49–59.

Kobus S, Bologna F, Maucher I, Gruenen D, Brandt R, Dercks M, Debus O, Jouini E. Music therapy supports children with neurological diseases during physical therapy interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022a;19(3):1492.

Kobus S, Buehne AM, Kathemann S, Buescher AK, Lainka E. Effects of music therapy on vital signs in children with chronic disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022b;19(11):6544.

Koshimori Y, Kang K, Devlin K, Pantelyat A. Music for movement disorders. In: Devlin K, Kang K, Pantelyat A, editors. Music therapy and music-based interventions in neurology: Perspectives on research and practice. Cham (CH): Springer Int Pub; 2024. p. 49–70.

Magill L. The meaning of the music: The role of music in palliative care music therapy as perceived by bereaved caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(1):33-39.

Mercier LJ, Langelier DM, Lee CH, Brown-Hall B, Grant C, Plamondon S. Effects of music therapy on mood, pain, and satisfaction in the neurologic inpatient setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(18):2964-2975.

Mistraletti G, Solinas A, Del Negro S, Moreschi C, Terzoni S, Ferrara P, et al. Generalized music therapy to reduce neuroactive drug needs in critically ill patients. Study protocol for a randomized trial. Trials. 2024;25(1):379.

Modrykamien AM. Enhancing the awakening to family engagement bundle with music therapy. World J Crit Care Med. 2023;12(2):41-52.

Ormston K, Rose E, Gallagher K. George’s lullaby: A case study of the use of music therapy to support parents and their infant on a palliative pathway. J Neonatal Nurs. 2022;28(3):203-206.

Ortiz GS, O’Connor T, Carey J, Vella A, Paul A, Rode D, et al. Impact of a child life and music therapy procedural support intervention on parental perception of their child’s distress during intravenous placement. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(7):498-505.

Palumbo A, Kim SJ, Raghavan P. Music for stroke rehabilitation. In: Devlin K, Kang K, Pantelyat A, editors. Music Therapy and Music-Based Interventions in Neurology: Perspectives on Research and Practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 23-35.

Pereiro Martínez S, Beck BD, Torres Serna E, Cobos Campos R, Argaluza Escudero J, Corral Lozano E. Music therapy during weaning from mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: Study protocol for a randomised control trial. Nord J Music Ther. 2024;34(2):124-144.

Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, et al. The effect of music on pain in the adult Intensive Care Unit: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(6):1304-1319.e6.

Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47(1):3-14.

Saldaña-Ortiz V, Caballero-Galilea M, Mansilla-Domínguez JM, Lorenzo-Allegue L, Martínez-Miguel E. Music therapy in intensive care: Family perspectives on humanising care. Collegian. 2025a;32(2):111-119.

Saldaña-Ortiz V, Martínez-Miguel E, Navarro-García C, Font-Jimenez I, Mansilla-Domínguez JM. Intensive care unit patients’ experiences of receiving music therapy sessions during invasive procedures: A qualitative phenomenological study. Aust Crit Care. 2025b;38(2):101109.

Schreck B, Loewy J, LaRocca RV, Harman E, Archer-Nanda E. Amplified cardiopulmonary recordings: Music therapy legacy intervention with adult oncology patients and their families—A preliminary program evaluation. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(9):1409-1412.

Seyffert S, Moiz S, Coghlan M, Balozian P, Nasser J, Rached EA, et al. Decreasing delirium through music listening (DDM) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated older adults in the intensive care unit: A two-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):576.

Shirasaki K, Hifumi T, Nakanishi N, Nosaka N, Miyamoto K, Komachi MH, et al. Postintensive care syndrome family: A comprehensive review. Acute Med Surg. 2024;11(1):e939.

Smith HAB, Besunder JB, Betters KA, Johnson PN, Srinivasan V, Stormorken A, et al. 2022 Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines on prevention and management of pain, agitation, neuromuscular blockade, and delirium in critically ill pediatric patients with consideration of the ICU environment and early mobility. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2022;23(2):e74-e110.

Steiner-Brett AC. The use of music therapy to address psychosocial needs of informal caregivers: An integrative review. Arts Psychother. 2023;84:102036.

Street A, Zhang J, Pethers S, Wiffen L, Bond K, Palmer H. Neurologic music therapy in multidisciplinary acute stroke rehabilitation: Could it be feasible and helpful? Top Stroke Rehabil. 2020;27(7):541-552.

Thaut MH, McIntosh GC, Hoemberg V. Neurobiological foundations of neurologic music therapy: Rhythmic entrainment and the motor system. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1185.

Tulin-Silver S, Asch-Ortiz G, Tsze DS. Music therapy for pediatric pain management during bedside sclerotherapy. J Vasc Anomalies. 2023;4(4):e074.

Walden M, Elliott E, Ghrayeb A, Lovenstein A, Ramick A, Adams G, et al. And the beat goes on: Heartbeat recordings through music therapy for parents of children with progressive neurodegenerative illnesses. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(7):1023-1029.

Wieczorek B, Ascenzi J, Kim Y, Lenker H, Potter C, Shata NJ, et al. PICU Up!: Impact of a quality improvement intervention to promote early mobilization in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(12):e559-e566.

Yinger OS. Music therapy as procedural support for young children undergoing immunizations: A randomized controlled study. J Music Ther. 2016;53(4):336-363.

Zhang TT, Fan Z, Xu SZ, Guo ZY, Cai M, Li Q, et al. The effects of music therapy on peripherally inserted central catheter in hospitalized children with leukemia. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2023;41(1):76-86.