ICU Management & Practice, Volume 24 - Issue 2, 2024

This article highlights some particularities to be considered when making decisions in paediatric ICUs and the role of parents (or legal guardians) and the physician in the dilemma involved in paediatric decision-making.

In these times, an ill individual is believed to be an autonomous moral agent to make decisions regarding their health. Decision-making inevitably requires correct information that must be provided by the healthcare team in an explicit and comprehensible manner. For that, the necessary time and adequate space should be dedicated. But what about the paediatric patient: are they autonomous moral agents?

There are emergency situations in which there is no time for informed consent. In these situations, the physician must make the decision according to their best moral judgement. In their actions, moral responsibility with a sense of holistic treatment and protection must be applied without attempting to mask a paternalistic approach. However, in most situations, which are unurgent, it is necessary to make a more considered decision involving other agents, like the child and their environment.

Paediatric Patient Autonomy

In decision-making, when it comes to competent adults, it is usually the patient, by virtue of the principle of autonomy, who consents and decides. However, when we face people who cannot express their opinion, as is the case in paediatrics, the main difficulty lies in deciding what is in the best interests of these people. How can we define the best course of action according to the interests of someone who cannot express them or even recognise them?

We will now consider the role of parents (or other legal guardians) and the role of the physician in the dilemma that may be involved in paediatric decision-making.

Ethics and law give parents the power to decide on medical interventions for minors. Their authority is ethically and legally incontrovertible. It is structured as a fiduciary function, which is exercised on behalf of and for the benefit of the incapacitated person (presuming his or her will). But should we consider all minor patients as legally incapable of making decisions? The acquisition of autonomy is a dynamic process, and logically, we cannot consider a newborn child whose decision-making capacity is nil in the same way as a seven-year-old child or a fourteen-year-old adolescent. The latter may often be capable of making decisions in matters that affect him or her from the point of view of health and who may make demands to maintain his or her privacy and autonomy from his or her parents.

An individualised study of each case is necessary to assess the maturity of the minor and the importance of the decision. It is incorrect to consider a decision on which the life of the adolescent may depend the same as others whose consequences may be less serious. The greater the complexity of the decision, the greater the degree of maturity required.

It is particularly in these circumstances that parents or other legal guardians will have a much greater role to play. The parent's view of the child's best interests will obviously be of paramount importance in decision-making. This view will often coincide with that of the physician, but at other times it may be markedly discordant, although this does not mean it is wrong per se.

Even so, there are situations in which we observe their point of view with reservation, and it is desirable they do not assume the weight of the decision:

- When they are unable to understand the most relevant aspects of the case.

- When they show significant emotional instability, especially if this provokes a change of opinion between the decisions to be taken.

- When they place their own interests before those of their children.

In the first case, it is necessary to ensure the parents' level of information is optimal. That is to say, that they understand in an accurate way the information communicated about the diagnosis, the prognostic judgements and the treatment. It is necessary to avoid technicalities and make it easily intelligible, adapting it to the parents' level of assimilation, as well as repeating it frequently and when requested.

The second and third cases are more complex. If the situation allows it and the decision can be delayed without any harm, further discussion can be encouraged later. In cases where this is not possible, the professional responsible for the patient should communicate with the unit referent and the rest of the team to establish the best course of action. It should be remembered that the doctor is also the guarantor of the patient's health. If, either because of emotional instability or because of putting one's own interests first, a family makes a clearly detrimental choice to the child, it should not be carried out. Some resources may be necessary for the family to understand the best interests of the child. The role of nursing is also key, given its constant proximity to the patient, as well as that of the psychology, social work, or spiritual care team. Even so, if disagreement persists, there is the possibility of convening the health care ethics committee and, as a last resort, taking legal action.

The Figure of the Mature Minor

From what age is a patient's autonomy considered? In Spain, for example, the legal and criminal age of majority is 18. In contrast, the age of majority in healthcare is a legal concept incorporated by the Basic Law on Patient Autonomy and is established at the age of 16 (except in exceptional situations) or by emancipation, provided that the person is not considered incapacitated or incapable. Below this age, between 12 and 16 years of age, the figure of the mature minor is recognised. The mature minor is understood as a minor with sufficient capacity to make decisions in relation to a specific action. In other words, a patient who understands the information provided by the medical staff and the situation in which he or she finds him or herself and who, in addition, gives reasonable grounds for his or her decision, weighing up the risks and benefits of the various options.

The figure of a mature minor should be recognised by the physician, who should assess the minor's capacity to make decisions in specific matters in a progressive manner according to their age, degree of maturity, development, and personal evolution. If not considered mature, proxy consent should be considered. In practice, in intensive care units, given the critical state of the patients, it is very challenging to assess the degree of maturity of the minor, and in most cases, consent by representation is assumed.

The Complex Chronic Patient

In paediatrics, a complex chronic patient (CCP) is defined as a patient with a disease, or more than one, of a long evolution and with a clinical situation that is difficult for professionals to manage. These patients represent around 5% of the population and consume approximately 65-75% of healthcare resources. They have changing needs that require continuous reassessment and necessitate the orderly use of different levels of care and, in some cases, health and social services.

CCPs are often dependent on technology (tracheostomy, home ventilation, gastric button...) and, due to their frailty, require regular hospital admissions in the context of intercurrent diseases. Both throughout the course of their illness and during these admissions, the patient's baseline situation and the therapeutic horizon (whether it will improve over time or, on the contrary, will progressively deteriorate) must be assessed, and the family must be aware of the latter. Depending on these factors and the severity of the decompensation, the place of admission for these patients should be chosen. Sometimes, these patients are subject to a therapeutic ceiling (e.g. no admission to the PICU, no resuscitation manoeuvres, etc.), especially when they do not achieve a minimum quality of life.

According to Francesc Abel, one of the pioneers of bioethics in Europe and founder of the Borja Institute of Bioethics, "human life is not a supreme good in itself but is dependent on other values that can be achieved with it and that give it meaning". In general, it is necessary to assess whether an insufficient quality of life exists in the following cases: severe intellectual retardation, deprivation of the minimum capacity to relate to the environment, permanent immobility, and absence of cognitive and motor development. Therefore, the minimum quality of life to be preserved could be understood as a minimum capacity for affective and intellectual relationships with others.

Thus, in these patients, measures that could be provided and proportionate in other patients may be totally disproportionate and lead to therapeutic obstinacy, contrary to professional ethics. We must examine diagnostic or therapeutic medical practices that are not indicated due to the high risk of side effects and/or suffering in relation to the little benefit that can be obtained.

Positions of Vitalism-Abstentionism

In severe situations, we can define two types of attitudes that we consider incorrect as extremes of a spectrum of decision-making. On the one hand, vitalist attitudes can be proposed in situations in which it would be more reasonable to carefully delimit therapeutic actions (unrealistic or miraculous hopes of improvement or cure, cultural reasons and even acceptance of extremely complex situations that are assumed to maintain family dynamics). On the other hand, in a competitive and perfectionist society such as the one in which we find ourselves, abstentionist positions may be proposed from the therapeutic point of view, fearing precisely the survival of a child with certain disabilities or to whom they would have to dedicate more time and effort than desired.

Finally, although fortunately less frequent, there may be situations of agreement between certain healthcare professionals and the family that are not in the best interest of the patients. This can happen not merely with our PICU team but also when dealing with other teams (e.g. oncohaematology, cardiology, neurology, etc.). On the one hand, unrealistic messages or a very partial view of the patient (limited to their specialty) are sometimes conveyed to the family. Communication between the different people in charge is essential, as well as for everyone to have communication skills that allow them to speak honestly about the prognosis of different illnesses when these are relevant in relation to their quality of life and life expectancy. On the other hand, the growing interest in the diagnosis and treatment of new so-called rare diseases can lead to therapeutic obstinacy, encouraged by both specialists and families. In these situations, the proportionality of the different therapeutic measures needs to be carefully balanced, especially in the context of critical situations.

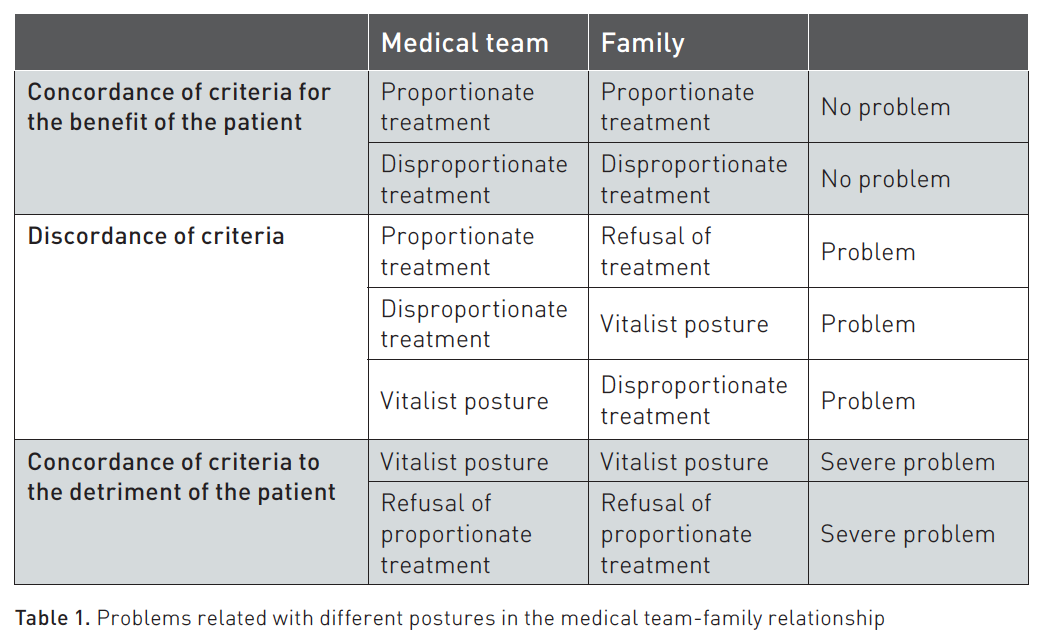

The following table outlines the various situations that can occur in the doctor-family relationship and the different problems they may present. This is obviously a theoretical level, but it allows the various aspects of the problem to be considered and analysed.

Confrontational situations can be challenging and tremendously problematic, creating situations of moral distress for intensive-care professionals.

The ideas expressed in this article may be of interest not only for decision-making in paediatric intensive care but also for many other situations in which the patient is not an autonomous moral agent to decide (neurodegenerative diseases, psychiatric pathologies, patient severity...). It is always advisable to individualise each case and invest the necessary time to clarify the situation. Currently, it is desirable that the opinion of the entire care team coincides, and consensus with the family is necessary. Every so often, the family simply requires more time to understand the situation and its implications. Even so, if consensus is not achieved or if the time is excessive to the detriment of the child, the resources previously discussed in this text should not be forgotten.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Bobillo-Perez S, Segura S, Girona-Alarcon M et al. (2020) End-of-life care in a pediatric intensive care unit: the impact of the development of a palliative care unit. BMC Palliat Care. 19(1).

Garros D, Austin W, Carnevale FA (2015) Moral distress in pediatric intensive care. JAMA Pediatr. 169(10):885.

Garros D, Rosychuk RJ, Cox PN (2003) Circumstances surrounding end of life in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 112(5):e371–e371.

Launes C, Cambra F-J, Jordán I, Palomeque A (2011) Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments: An 8-yr retrospective review in a Spanish pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 12(6):e383–5.

Limitación terapéutica en pediatría (2024) Tienda virtual Sant Joan de Déu - Campus Docent. Available at https://ediciones.santjoandedeu.edu.es/profesionalidad/30-limitacion-terapeutica-en-pediatria.html