ICU Management & Practice, Volume 25 - Issue 1, 2025

The critical care environment is a stressful work setting for physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals who provide care to critically ill patients. As a result, critical care clinicians are at risk for experiencing burnout. Addressing organisational, individual, and care related factors that are associated with an increased susceptibility to develop burnout in critical care can help to mitigate and prevent burnout and promote well-being in critical care.

Overview

The fast paced, often unpredictable nature of the work environment in critical care can be stressful for physicians, nurses, advanced practice providers, and other healthcare professionals providing care to patients with life-threatening conditions. Additionally, long work hours, shift rotations, on-call time, staffing conflicts, moral distress, and providing emotional support to patients and their family members can place critical care clinicians at risk for experiencing burnout (Moss et al. 2016). Burnout syndrome is characterised by three psychological domains: (1) emotional exhaustion, (2) depersonalisation, and (3) lack of personal achievement (Maslach and Leiter 2016). Burnout is a state of emotional, mental, or physical exhaustion brought on by prolonged or repeated stresses at work (Mealer et al. 2016).

Burnout is recognised as a major contributor to physician and nurse turnover and reduced work hours (Pastores et al. 2019; Hodkinson et al. 2022; Niven and Sessler 2022). Burnout also has financial and quality implications for healthcare systems and can adversely impact well-being and team dynamics (Hodkinson et al. 2022; Mehta et al. 2022; Niven and Sessler 2022; Papazian et al. 2023; Pastores et al. 2019). Strategies that address key drivers of burnout, enhance unit-based teams, and support individual resiliency are important to reduce critical care professional burnout and improve patient safety and outcomes (Niven and Sessler 2022).

Risk Factors and Consequences

Organisational, individual, and critical care related factors are associated with an increased susceptibility to develop burnout in critical care. Organisational risk factors such as understaffing, administrative burden, and lack of control over the work environment can promote burnout in the critical care setting. Additionally, critical care specific risk factors such as providing care to high acuity patients, variability in work schedules, navigating ethical issues and end-of-life care and complex care decision making also place critical care clinicians at risk. Individual factors for critical care related burnout can include overcommitment, being self-critical, and having unrealistically high expectations (National Academy of Medicine 2016; Hodkinson et al. 2022; Mehta et al. 2022; Niven and Sessler 2022; Papazian et al. 2023; Pastores et al. 2019; Ramirez-Elvira et al. 2021).

While there are numerous drivers of burnout, a simplified approach supports focusing first on the work and the workers. Both the quantity and the quality of the work matter. Specifically, long hours, work at night and on weekends, and even the intense concentrated daily work performed in the critical care unit can contribute to burnout. While caring for critically ill patients is meaningful, work in healthcare – including the critical care unit – is fraught with time consuming tasks such as excessive documentation. Critical care professionals are accustomed to working hard – but it is critical that there are adequate support and resources to do this hard work, as well as time for worker decompression and recovery to avoid burnout.

In regard to the people doing the work, critical care is a team sport and the quality of relationships, and the culture of the unit is immensely important. Workplace conflict is unfortunately common and is a key driver of burnout for physicians, nurses and other members of the healthcare team. Achieving mutual respect, collaboration, civility, and trust among team members requires constant attention and open dialogue (AACN 2024). Effective communication within the ICU team is key as is communication with institutional leaders to achieve alignment of vision and values (Moss et al 2016). Finally, when considering the importance of the work and the workers in mitigating burnout, it is critical to acknowledge that critical care professionals are first and foremost people – who have busy lives outside of work.

Relevant Research

A number of studies, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted on burnout in critical care physicians and nurses. One systematic review evaluated 25 studies that measured burnout using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a frequently used tool to estimate the prevalence of high-level burnout among physicians and nurses. The studies had a combined sample size of 20,723, including 8187 physicians and 12,536 nurses (Papazian et al. 2023). Of 8187 ICU physicians, 3660 reported high-level burnout (Papazian et al. 2023). The overall weighted prevalence of high-level burnout in physicians across 18 studies was 0.41, ranging from 0.15 to 0.71. Of the total of 12,536 ICU nurses included, 6232 reported high-level burnout. The overall weighted prevalence of high-level burnout in nurses across 20 primary studies was 0.44, with a range from 0.14 to 0.74 (Papazian et al. 2023). Additionally, when subscale results were evaluated, the proportion of high-level exhaustion was higher among nurses (Papazian et al. 2023).

A multicentre mixed-methods cohort study conducted in critical care units at three diverse hospitals recruited physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and other staff members who completed the MBI and a qualitative focus group or interview using a phenomenological approach (Mehta et al. 2022). Fifty-eight providers (26 physicians, 22 nurses, six respiratory therapists, three pharmacists, and one case manager) participated. Participants scored moderate or high levels across the three MBI subscales (emotional exhaustion, 71.4%; depersonalisation, 53.6%; and lack of personal achievement, 53.6%). Drivers of burnout aligned with three core themes: patient factors, team dynamics, and hospital culture. Individual drivers included medically futile cases, difficult families, contagiousness of burnout, lack of respect between team members, the increasing burden of administrative or regulatory requirements at the cost of time with patients, lack of recognition from hospital leadership, and technology challenges (Mehta et al. 2022).

Strategies for Addressing Burnout in Critical Care and Promoting Wellness

As clinician burnout is a complex and multifaceted problem, there is no single solution to achieve the needed changes (NAM 2019). Health care organisations should focus on the development, implementation, and evaluation of organisation-wide initiatives to reduce the risk of burnout, foster professional well-being, and enhance patient care by improving the work environment (NAM 2019).

Promoting a Healthy Work Environment

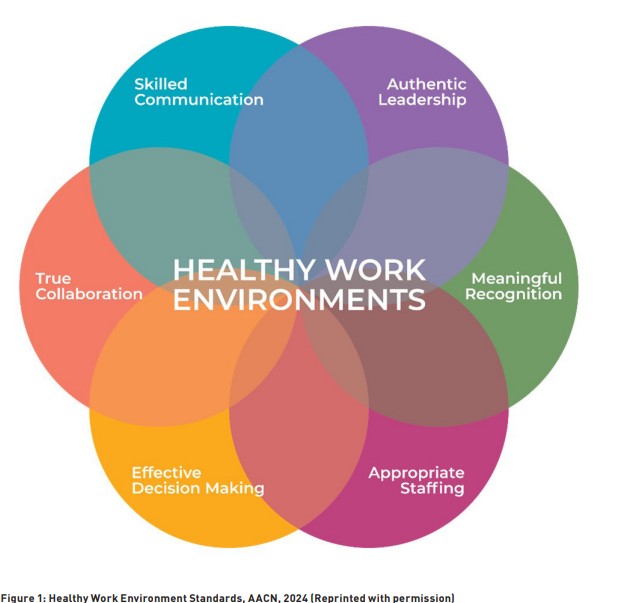

Establishing and sustaining a healthy work environment that fosters respect may be one key strategy to combat stress and burnout in the acute and critical care work environment. The importance of maintaining a healthy work environment underlies many organisational initiatives to mitigate burnout and enhance wellness. In 2001, the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) established a strategic priority to improve the health of the healthcare work environment. In 2005, the AACN Standards for Establishing and Sustaining Healthy Work Environments were published in response to increasing evidence that unhealthy work environments contribute to medical errors, ineffective delivery of care, and conflict and stress among health care professionals (AACN 2024). The standards provide an evidence-based framework for organisations to create work environments for health care professionals to practice to their full potential, ensuring optimal patient outcomes and professional fulfilment (AACN 2024).

The standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments are outlined in Figure 1.

Stress Management

A systematic review of 12 studies with 592 participants explored specific interventions to reduce burnout in ICU nurses and found that cognitive behavioural skills training and mindfulness-based programmes were more effective in reducing occupational related stress (Alkhawaldeh et al. 2020). Six studies used cognitive-behavioural skills training (emotional regulation training, neuro-linguistic programming, resilience training, emotional intelligence, assertiveness training, and time management); three studies used mindfulness-based training; and one study used massage, yoga, and aromatherapy. The length of the intervention period ranged from 4 to 24 weeks; however, most studies delivered interventions for 6 weeks or less (Alkhawaldeh et al. 2020). The authors identify six studies supporting cognitive-behavioural skills to increase ICU nurses' ability to cope with stress. However, the studies used different types of cognitive-behavioural interventions and different assessment instruments to measure effectiveness, limiting the generalisability of the results (Aklhawaldeh et al. 2020).

Creative Arts Therapy

The use of a 12-week creative arts therapy programme was examined in a clinical trial with 144 healthcare worker participants who attended weekly 90-minute group sessions led by a trained therapist (Mantelli et al. 2023; Moss et al. 2022). Participants included nurses, physicians and behavioural health specialists randomised to 1 of 4 creative arts therapy groups or to a control group. Intervention groups included creative writing, dance and movement, music, and visual arts. All participants completed surveys assessing psychological distress at baseline at 12 weeks, and at 4, 8 and 12 months. The creative arts therapy group demonstrated sustained improvement in distress scores for anxiety, depression and affect at 4 and 8 months postintervention (Mantelli et al. 2023; Moss et al. 2022). During the 12-month period, the creative arts group demonstrated sustained improvement in anxiety, depression and affect compared with the control group (Mantelli et al. 2023; Moss et al. 2022). The authors conclude that creative arts therapy has lasting benefits for healthcare professionals and represents another intervention that can be used to address burnout.

Fostering Professional Well-Being

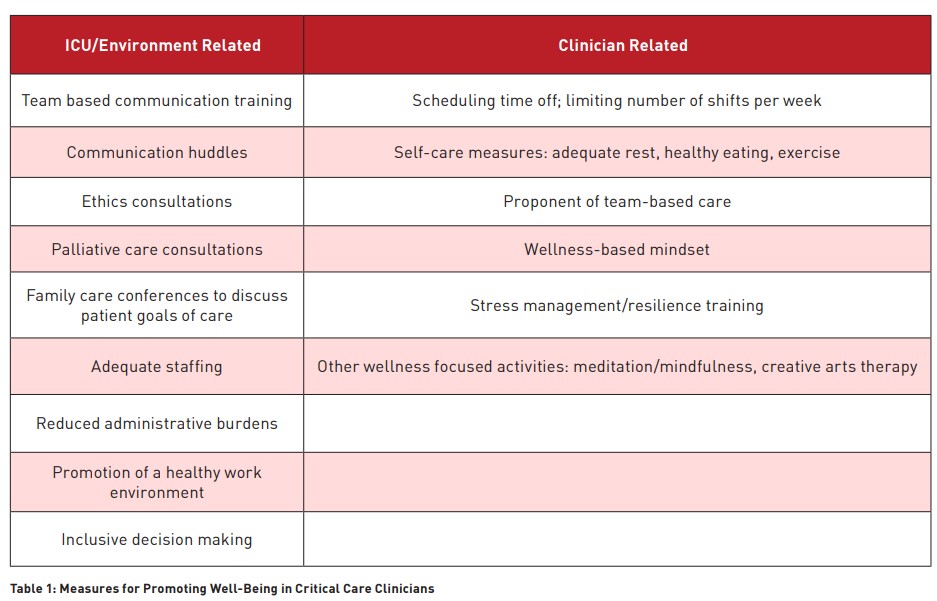

A number of measures can be helpful to critical care clinicians to promote professional well-being. These include taking rest and meal breaks when at work; scheduling time off and limiting the number of shifts per week; and self-care measures such as ensuring adequate rest, healthy eating habits, and exercise. Participating in team huddles and debriefings, use of ethics consultations, palliative care consultations and family care conferences can also be useful for balancing the demands of critical care (Moss et al. 2016; Kleinpell et al. 2020). Other measures include providing adequate staffing levels to manage patient workload, implementing stress management programmes, and fostering a supportive team culture that prioritises well-being (Table 1).

Recognising the importance of fostering the well-being of healthcare professionals, many health systems include health and wellness resources for clinicians, including exercise facilities, counselling services, and mental health resources.

A recent study examined the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention for improving well-being of critical care staff over a 2-year period. Interventions included social activities, fitness, nutrition, and emotional support (Lovell et al. 2023). Well-being of critical care staff was assessed with a convenience sample before (n = 96) and after (n = 137) the intervention. Focus groups were also held to explore participants’ perceptions of the intervention's effectiveness. Well-being scores after the intervention (mean = 6.95, standard deviation = 1.28) were not statistically different (p = 0.68) from baseline scores (mean = 7.02, standard deviation = 1.29) (Lovell et al. 2023). Analysis of focus groups data revealed three key categories: boosting morale and fostering togetherness, supporting staff, and barriers to well-being (Lovell et al. 2023). The authors highlight that an organisational focus on well-being that promotes critical care staff to flourish through positive affect, social connections, and building of resilience can potentially reduce the risk of psychological pathology and increase staff members' capacity to provide compassionate, patient-centred care (Lovell et al. 2023).

A cross-sectional survey study among 193 critical professionals examined opinions related to the work environment (van Mol et al. 2018). Work engagement was negatively related both to cognitive demands among intensivists and to emotional demands among critical nurses. No significant relationship was found between work engagement and empathic ability; however, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability were highly correlated with work engagement. Only the number of hours worked per week remained a confounding factor, with a negative effect of workload on work engagement after controlling for the effect of weekly working hours (van Mol et al. 2018). The authors conclude that work engagement counterbalances work-related stress reactions.

Other factors that promote well-being in critical care include daily rounds to acknowledge team-based efforts, authentic leadership, including family and friends as part of the critical care team, and focus on care that integrates clinical practice, teaching and research (Vincent 2018).

Conclusions

Providing a healthy work environment is essential in the mitigation and prevention of burnout and in promoting clinician well-being. Awareness of the causes, consequences, and strategies to manage and prevent burnout and promote well-being in the critical care setting is essential.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Alkhawaldeh JMA, Soh KL, Mukhtar FBM, Peng OC, Ashasi HA. Stress management interventions for intensive and critical care nurses: a systematic review. Nurs Crit Care. 2020;25:84-90.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Healthy work environment standards [Internet]. Available from: https://www.aacn.org/~/media/aacn-website/nursing-excellence/healthy-work-environment/execsum.pdf?la=en

Gomez S, Anderson BJ, Yu H, et al. Benchmarking critical care well-being: before and after the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0233.

Haslam A, Tuia J, Miller SL, Prasad V. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials testing interventions to reduce physician burnout. Am J Med. 2024;137:249-57.

Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442.

Kelsey EA. Joy in the workplace: the Mayo Clinic experience. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;17(3):413-7.

Kerlin MP, McPeake J, Mikkelsen ME. Burnout and joy in the profession of critical care medicine. Crit Care. 2020;24:98.

Kester K, Pena H, Shuford C, et al. Implementing AACN’s Healthy Work Environment Framework in an intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2021;30(6):426-33.

Kleinpell R, Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, Sessler CN. The critical nature of addressing burnout prevention: results from the Critical Care Societies Collaborative's National Summit and survey on prevention and management of burnout in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(2):249-53.

Lovell T, Mitchell M, Powell M. Fostering positive emotions, psychological well-being, and productive relationships in the intensive care unit: a before-and-after study. Aust Crit Care. 2023;36:28-34.

Mantelli RA, Forster J, Edelblute A, et al. Creative arts therapy for healthcare professionals is associated with long-term improvements in psychological distress. J Occup Environ Med. 2023;65:1032-5.

Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103-11.

Mealer M, Moss M, Good V, Gozal D, Kleinpell R, Sessler C. What is burnout syndrome (BOS)? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(1):P1-2.

Mehta AB, Lockhart S, Reed K, et al. Drivers of burnout among critical care providers. Chest. 2022;161:1263-74.

McKenna J. Medscape physician burnout & depression report 2024: "We have much work to do" [Internet]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2024-lifestyle-burnout-6016865?icd=login_success_email_match_norm#3

Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, Kleinpell R, Sessler C. An official Critical Care Societies Collaborative statement: burnout syndrome in critical care healthcare professionals: a call for action. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-21.

Moss M, Edelblute A, Sinn H, et al. The effect of creative arts therapy on psychological distress in healthcare professionals. Am J Med. 2022;135:1255-62.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Taking action against clinician burnout: a systems approach to professional well-being. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. p. 63-72.

Niven A, Sessler S. Supporting professionals in critical care medicine. Clin Chest Med. 2022;43:563-77.

Papazian L, Hrajeck S, Loundou A, Merridge MS, Boyer L. High-level burnout in physicians and nurses working in adult ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:387-400.

Pastores SM, Kvetan V, Coopersmith CM, et al. Workforce, workload, and burnout among intensivists and advanced practice providers: a narrative review. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:550-7.

Ramirez-Elvira S, Robero-Bejar JL, Suleiman-Martos N, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and burnout levels in intensive care unit nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11432.

van Mol MMC, Nijkamp MD, Bakker J, et al. Counterbalancing work-related stress? Work engagement among intensive care professionals. Aust Crit Care. 2018;31:234-41.

Vincent JL. 12 things to do to improve well-being in the ICU. ICU Manag Pract. 2021;21:66-8.