HealthManagement, Volume 10, Issue 2 /2008

Author:

Prof. Dr. med. Ottmar Leiß

Internist and Gastroenterologist

Gastroenterologische Gemeinschaftspraxis, Mainz, Germany

Email: [email protected]

According to the philosopher Odo Marquard (1), “The dominant trend

of modern global change is towards uniformity. Distinctions are being

neutralised. It is only through this process that the hard sciences can deliver

globally verifiable results; it is only through this process that technology

can replace global traditional realities with functional realities; it is only

through this process - recourse to the one-size-fits-all mechanism of money for

instance – that the modern economy can turn products into globally traded

goods; only through alignment with the best in the world and the acquisition of

the cheapest in the world is global progress possible.”

This trend towards global uniformity and the increasing independence of the means of production, labour and capital from location and tradition are encapsulated in the buzzword “globalisation”. It is precisely because modern science, technology and economics function in a tradition-neutral manner and modern in formation media, independently of traditional languages, communicate digitally and to an increasing extent globally that that which is new, the future, will become increasingly origin-neutral.

Aspects of Globalisation

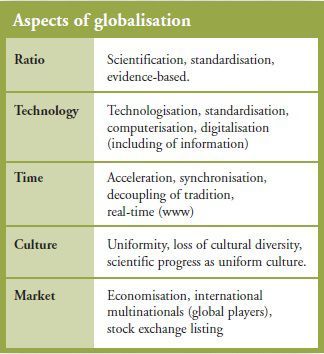

It is possible to formally differentiate various aspects of the globalisation process which are interdependently mutually reinforcing and contribute to the acceleration in the overall process.

From the perspective of society as a whole, objectivisation, standardisation and normalisation in science and production encourage cooperation across borders and cultures. Rationality and the rationalisation of work processes facilitate automation and technologisation, which, in turn, fosters standardisation and internationalisation. Information technology is one of the prime catalysts in this process.

What does Globalisation Mean for Medicine

as a Science?

Where medicine is an applied science and avails of new techniques and technologies (for example, information technologies), it benefits from globalisation, standardisation and progress. In many cases, technological innovations have been pre requisites for new insights. Through the use of macroscopes, microscopes and endoscopes, for example, we have gained new insights that have helped to create breakthroughs in our under -standing (2). The trends towards objectivisation, uniformity and technologisation in the globalisation process make no allowances for the evolution of tradition, culture and life-history. In this respect, integrative concepts in medicine, such as Engel’s biopsychosocial model (3), and health concepts which complement the pathogenetic orientation of medicine, such as Antonovsky’s salutogenesis (4), are in a difficult position because they have not (yet?) entered mainstream current thought.

Is Globalisation Changing Hospitals and

Medical Practices?

Rationalisation, uniformity and technologisation encourage the transformation of hospitals into medical service centres (5). The hospital doctor is evolving into a technician and becoming increasingly dependent on medical technicians and IT specialists. The complexity of modern medicine requires close interdisciplinary cooperation and communication and participation in continuing education. Standards must be observed and evidence translated into practice. The economisation of internal hospital procedures reduces individual patients to cases, while colleagues become competitors. “Group egoism” must be rolled back, conflicts managed (6), hierarchies dismantled, goals achieved and quality safeguarded (7, 8). Political conditions, markets and competition among hospitals encourage cherry-picking and the “McDonaldisation” (9, 10) of the health service.

What does Globalisation Mean for Doctors

and Patients?

From the patient’s perspective, recent developments have delivered much that is positive. The objectification of medical services strengthens the autonomy of patients (12) and “demystifies” the doctor-patient relationship. Normative rules laid down by lawmakers (e.g. legislation on medical devices) have enhanced the safety of invasive interventions in which medical de vices are used, while guidelines (13, 14) encourage safetyand prescribing security and offer patients transparencyvis-à-vis the standards they can expect. Asbranding and specialisation among practices increase,more alternatives become available at local level, andorganisational professionalism and customer-orientationimprove (the introduction of after-hours consultations,for instance), the patient is assuming the roleof client and the customer is becoming king. Old-fashionednotions of mutual trust and loyalty are in declineas changing social values create a “thrill-seekingsociety” in which temporary partnerships and “doctorshopping” (mainstream medicine, alternative therapies,acupuncture and so forth) are on the increase.

For doctors, too, progress and globalisation have both advantages and disadvantages. The Verwissen schaftlichung (scientification) of medicine means more rational and critical evaluation of diagnostic and therapeutic measures is indispensable. Only outcomes that have been achieved using placebo-controlled, double-blind studies may be described as evidence-based medicine and elevated to the standard or state-of-the-art approach. Because the experience of the individual is both deceptive and inadequate, technologies and options for accessing “objective knowledge” (databases) are becoming more and more important for rational action. Computer skills (the ability to perform electronic searches, download and update) are now more important than knowledge of percussion and auscultation.

Why the Unease About Progress and Globalisation?

Science and technology, the engines of progress and globalisation, are Trojan horses: we do not know what is hiding inside. The explosion in rationalisation stokes emotional fears and fosters suspicion, while the dimini - shing marginal utility of further progress creates scepticism. Can people tolerate an infinite amount of innovation? No, they cannot (15). “Conditioned by the brevity of life, people can never emerge far or quicklyfrom their “original skin”, so to speak, and they certainly cannot shed it completely. For this reason, they are fundamentally lethargic in the face of change, in other words, while they may be experts in modernisation, people are essentially slow (16).”

If we want to avoid being overrun by globalisation and if want to survive in a world of accelerating change, we must – from a salutogenic perspective – create coherence between the old and the new.

Conclusion

The benefits of globalisation for medicine as a science and medical-technical system lie in information technology, the digitalisation of imaging processes and the internationalisation of scientific interpretation constructs.

The danger facing medicine is that its role will diminish until and become one of disease management, doctors will become “strangers in medicine” (17) and people will no longer ask critical questions about how much medicine we really need (18). True medicine – medical help and relief (as well as the rare cases of healing) - is not global and universal but local and individual. The sick patient needs a doctor who is more than an illness manager or a brilliant technician or pill prescriber, he needs a doctor who will, to the limits of his ability and with empathy, endeavour to shape the way in which the patient copes with his illness (19).

To return to Odo Marquard: “The faster the process of modernisation, the more indispensable and important the slow among us become because the new world cannot exist without the old accomplishments. Humanity without modernity is lame; modernity without humanity is cold: modernity needs humanity because the future needs origin (16).”

The bibliography can be requested at [email protected].

Author:

Prof. Dr. med. Ottmar Leiß, Internist and Gastroenterologist

Gastroenterologische Gemeinschaftspraxis, Mainz, Germany

Email: [email protected]