HealthManagement, Volume 22 - Issue 4, 2022

Key Points

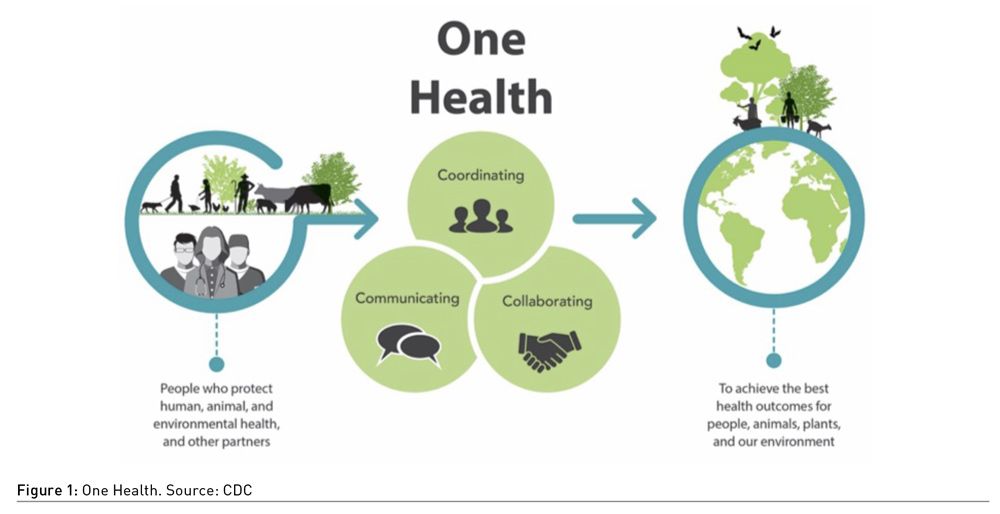

- One health is an approach that recognises that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment. One Health as a driving concept has become more important in recent years.

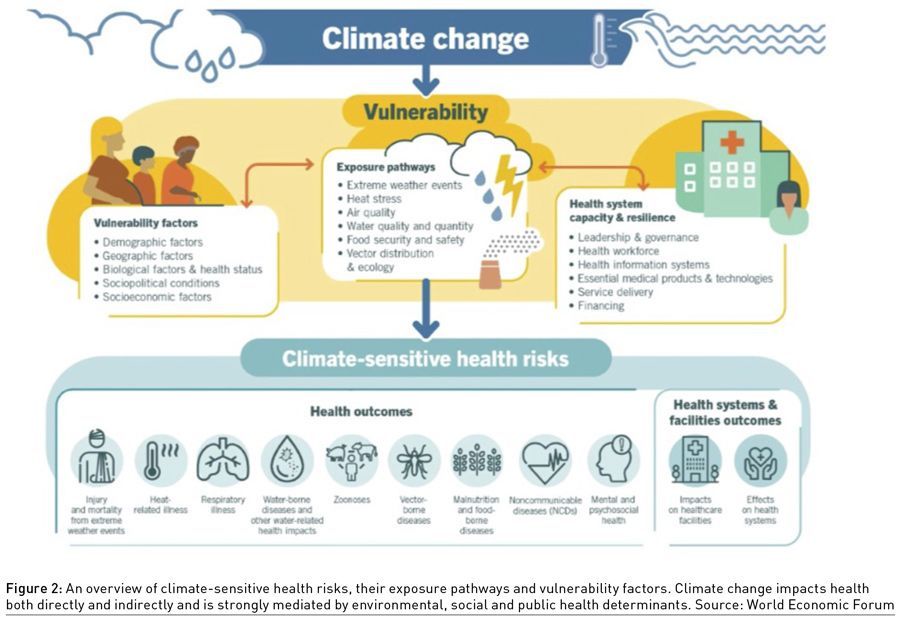

- Climate change is undermining many social determinants for good health, such as livelihoods, equality, access to healthcare, and social support structures.

- Public administration is the non-political public bureaucracy operating in a political system; it deals with the ends of the state, the sovereign will, the public interests and laws.

- Public Management is in charge of delivering the service and programmes of the public administration. Its commitment is the research of maximising efficiency and promoting the best methods.

- Healthcare public management is the complex of norms, rules, and forms of organisation to run a single healthcare unit or complex unit in a defined territory or a system. Its operational role and functionality are, at the present time, extremely important.

- The recurrent economic crises produced a progressive change also in public management. New Public Management (NPM) was characterised by an emphasis on cost-cutting, competition and the use of methods and goals from the private sector.

Framework

We are in difficult times. It is not necessary to use many words to prove it: an unforeseen pandemic, an unexpected war, a worsening economic crisis, and the amplification of social inequalities. On top of the list are the dramatic challenges posed by our overwhelming enemy: climate change.

Scientists have demonstrated that the effects of climate change have penetrated all aspects of our life. Until some time ago, a part of us, from scientists to researchers, from doctors to politicians, had reached a conclusion, a bit naively or too optimistically, that we were winning the battle against COVID-19, and our major objective was to return to the pre-pandemic status, simply taking into account some of the lessons learned.

In trying to understand where we are going and where we should be going, this article will focus on the field of public administration, paying specific attention to the health sector. The experience of COVID-19 has helped the diffusion of the consciousness that health is one of the most important factors, the strongest potential connector and influencer of many other areas. The paradigm One Health that the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union (EU) keep stressing, has made us more aware that the pursuit of human and planet health, on the one hand, and the fight against climate change, on the other hand, are two sides of the same coin.

In the framework of what we said above, we will explore the emerging need for change in public management, with a special focus on healthcare management. The selection of this theme for these reflections comes from, among others, these considerations. One comes from looking at a larger field than healthcare: public administration. Scholars dealing with this area have underlined that never before was there a greater need for highly performant public services and consequently for good managers running them. The same is certainly true for the public healthcare sector, especially after the pandemic.

Another consideration comes directly from the healthcare domain. We have seen in recent times loads of webinars, conferences, and articles focused on the lessons learned for hospital facilities, innovative models for new hospitals and/or revisions of the existing facilities, new materials for better resilience of hospitals etc., that can better develop concepts such as resilience, redundancy, improvement of materials and systems and other enhancements related to the physical infrastructures of healthcare, helping mitigation, energy efficiency etc., increasing preparedness for future pandemics and/or climate-related disasters. It is important to have a deep analysis of such subjects, but this is not sufficient for changing the delivery of care to people.

In fact, very little discussion is going on, to our knowledge, about management, governance, and the ability of public health systems to deliver healthcare. These are aspects appropriately called the “immaterial infrastructures” of healthcare. The attention is mostly on technology, digitisation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), virtual reality, and telemedicine. These are also useful, but again, not sufficient.

In this framework, we will address our attention to public management, defining some characteristics that appear fundamental for public healthcare delivery. This also makes it necessary to consider the figure of a public healthcare manager, who has the task of laying down the ground principles, programmes and plans made by the healthcare policymakers.

Relevant Steps in the Evolution of Public Healthcare Management

We will concentrate on Europe, supported by the knowledge of a few countries with which we have more acquaintance. At the end of World War II, in most European countries, there were deep signs of destruction in the cities, including the hospitals. Progressively reconstruction went on, mostly based on old models and criteria. The quality of the hospitals of this period is well defined by experts in the French health sector: HLM hospitals - buildings with the same low quality and construction metric costs as popular public housing. The care offered was old style, and the organisation was based on a model defined as bureaucratic and dependent on the national government for rules and financing. In many countries, the persons in charge of the general management had the status of an employee, with an executive role and very limited, if any, decisional power. The ‘60s, called the years of the economic miracle, witnessed a growing activity in many sectors. The ’70s brought to the Western world the first petrol shock that produced a diffusive and unexpected economic crisis and a sudden reduction of public budgets that also touched the healthcare sector.

In several countries, however, tangible changes from the previous pre-war and immediate post-war continued. For example, in Italy, the SSN (National Health System with universal rights or healthcare) was finally established in 1979 and in Spain in 1986. In parallel were the reforms introduced by Margaret Thatcher in 1979 in the U.K. and Ronald Reagan in the U.S. in 1980. These started to be known and became attractive, mostly because they promoted measures of containment of public expenses, privatisation, and externalisation (contracting out part of the public services). Some drawbacks started to occur in countries where public financial support was more relevant for the healthcare sector. The healthcare sector came more under scrutiny because it was considered too expensive. The goal of hospitals becoming financially self-sustainable started to be considered normal at the political level and inside healthcare management. Logic and instruments produced and used in the private sector were introduced in public healthcare organisations. A typical example would be the change in Italian levels of health organisations: national government, regions, second level of power, and USL (local unit of healthcare). The latter was transformed into local health agencies ASL (with some regional variation of the name), having a strong economic imprint, with control on expenditure directly coming from the regions on which they were financially dependent.

The introduction of systematic logic and managerial instruments of the private sector in the public institution became the common guidelines, and public management was given the name of New Public Management (NPM).

In certain European countries, as in Italy, the non-discussed imperative became cuts. The reduction of the national budget for health produced fewer resources for the regions and ASLs. Cuts were made in employing new personnel, and substituting persons retiring; there was a reduction in hospital stay, elimination of small hospitals, and impoverishment of territorial infrastructures. All these factors left a permanent imprint on the public delivery of healthcare and, in recent times, were identified as largely responsible for the high level of COVID-19 diffusion and death rate, especially in Italy.

European countries with the Bismarck healthcare models of care had settled down originally with a private managerial logic, and they had possibly less need for adjustments. The NPM, however, started to draw criticism from many sides, especially when applied to healthcare, where it was seen as treating the patients as clients. Individuals seeking help for their health recovery were not simply consumers of government services. The recognition of the limits of the business approach, in conjunction with the political and economic crises at the end of the ‘90s, stirred the introduction of further changes visible in the healthcare sector. The public administration realised that the contraposition between public and private was no more possible. The public alone couldn’t take the full weight of the growing need for health services. Referring to all sets of services provided by the public administration, Professor Rhodes stated that there was a need to develop “a non-hierarchical form of government in which public and private healthcare participated in the realisation of public policies and the consequent fulfilment of public needs” (Rhodes 1997).

The main characteristic of the approach to healthcare management was that it was focused on the creation of consensus and participation around public choices, more than guided by authority. This was referred to as “governance”. Dr Donato Greco, in his presentation on the Italian Ministry of Healthcare programme “Getting Healthier”, stressed that the programme was “based on the need for cooperation between various actors … national administrators and local ones (regional, provincial, municipal) the world of school, work and industry, healthcare professionals, welfare organisations of private nature: everyone is called upon to collaborate… skills and responsibilities of various sectors should interact in the interest of improving population health” (Greco et al. 2008).

The weaknesses of the governance approach became evident. The first issue that emerged was that governance was possible, or at least easier, to bear fruit in national and local environments where the social context is sufficiently cohesive and inclined to share. The other critical issue was the need for a different style of public management. As already mentioned, the subsequent crises and the current situation stressed the need to search for new parameters even more.

What Kind of Public Management Do We Need for Healthcare?

It is useful to start this part by stressing that innovation and improvements in healthcare management were considered necessary even before the dramatic, unexpected events in which we were suddenly immersed and are still struggling, with the pandemic still among us and the Russia-Ukraine war still producing destruction and death.

Changes, in fact, had occurred in these last decades involving not only European countries but the entire planet but had not significantly penetrated the world of public management. A significant example comes from the healthcare front and concerns the low awareness shown until recently by hospital managers about the need to reduce CO2 and GHGs in healthcare facilities, an intensive energy consumer, to help the fight against climate change. In a survey included in a co-funded EU project in 2013, specifically addressed to hospitals managers of eight EU nations regarding measures for energy saving and the attitude toward the introduction of renewable energy, it emerged that their concerns were about the burden of personnel and medicines on the budgets of their health agency. They considered energy as part of maintenance costs; therefore, only as an item of cost, not even sufficiently relevant as such. Some said that the energy matter was a technical aspect and not part of their core concern as managers. Fortunately, this attitude has changed, but the healthcare system can and must do much more to fight climate change.

Looking at the whole situation, the emergencies of the present moment and the pre-existing challenge of recovery, we conclude with Prof Mochi Sismondi that “public institution should become increasingly oriented towards results rather than fulfilment of standardised duties ……. and precisely define the objectives in terms of their impact on citizens and businesses…. Another fundamental aspect is that, at least European dimension in which public management must move; anyone still thinking in exclusively national terms or, worse, within the narrow confines of a region would be inexorably inadequate to interpret the present and plan for the future”.

The present commitments, in fact, cannot be made only by a few countries. As the first step in Europe, the healthcare sector has to focus on increasing cohesion among European health systems. The public healthcare sector would harvest more results from greater interaction among healthcare systems. Considering, as an example, the common limits that have been established in the fight against rising temperatures, air, water and sea pollution etc. It is clear that such objectives require the collaboration of all European countries. Confrontation of different health systems can stimulate innovation and become a motivation for more appropriate use of the available technologies - from digitisation to AI and IoT.

We had occasion in other articles to stress the complexity characterising our historical period. Linear relations and the principle of cause and effect are insufficient to comprehend reality. The complex set of interconnections between and among different segments of our world requires the knowledge and use of the systems approach theory, a fundamental tool in understanding our present reality. Furthermore, having the possibility of help from data and advanced tools such as the ones provided by AI, we can also anticipate certain developments and get better prepared to mitigate their impact.

Formal rules (laws, regulations, etc.) together with informal rules (coordination tables, joint planning, codes of conduct and self-regulation) derived from the principles of governance of the public management are an important source of support but are simply fulfilling their bureaucratic goals.

Type of Public Managers to Achieve Recovery in Difficult Times

Public managers have common characteristics, even when working in different areas, some more specific to their sector. At a round table talk of Forum PA, Dr Angelo Tanese, head of the Healthcare Public Agency n.1 of the Metropolitan Rome area, stressed the need for healthcare public management to take a leap from the present performance. The public manager has to lead this path, having the consciousness to be the connecting link between the political level that provides the roadmap, goals and financial related means and the aggregate of people, and the material and immaterial instruments that enable the realisation of the outlined programmes. The round table included contributions from other participants from different levels: national, regional, municipal, and the Institute for national statistics.

What was brought home from this discussion and direct conversations with others exercising the public manager’s role in healthcare and other sectors? Let’s summarise the ones that appear to be the most important requirements, especially for managing the current recovery and moving towards the “new normal” in this historical period, in which it is wise to assume the permanence (for how long?) of the present multiple problems:

- Sense of responsibility and, in parallel, demand some decision-making power.

- Vision and perspective longer than we are used to at present.

- Clear and transparent plans and the flexibility to make changes in case of sudden and unexpected events.

- Maximum attention to new technologies, considering that they are tools and to know them to ensure correct use and maximise their usefulness (e.g. the digitisation of healthcare).

Some personal characteristics appear to be important, not to say essential:

- Capacity to exercise daily leadership, showing positive motivation, inducing the same attitude in personnel at any level.

- Ability to exchange data.

- Collaborating transversely, that is, with people of other disciplines.

- These are the essential factors for innovation:

- Planning with longer-term vision.

- Precision with flexibility and preparedness to unpredicted events.

- Acquisition of complexity tools and use of system analysis methodology.

- Speeding up digital transition and telemedicine.

- From hospital to the territory: the opening of the silos.

- Continuity of care: home as the centre of care.

- Participation in changes in the urban environment, seen as common ground with city policymakers for prevention.

- Ecologic transition: the awareness of the great contribution that healthcare should give.

Conclusion

Even if not as publicised as the events concerning the physical aspects of the health facilities, there is, at least among the professional insider’s reflection about the necessary, important and urgent changes in public healthcare management, as well as in general, all the segments of public management and consequently, the fundamental figure of the public manager.

The same managers express the importance of the feeling of community inside and among public services, the need to increase the trust in public administration and public services and engaging themselves for a better quality of public activity. They conclude that all this is necessary, the fundamental remaining the capacity to interact and work on the same bases.

No manager succeeds alone. From the above-reported roundtable, an initiative was launched to build a cross-sectoral network of public managers, a platform at present for Italy, then scalable to Europe and involving the private sector.

Back to the questions posed in this article, we can say that while facing these challenging times, it is certainly positive to know that the insiders consider change necessary, but they also express the recognition of how difficult this change is and how high an engagement is required in keeping it. Furthermore, it is not only healthcare that needs to exit from its silos. Cross-sectoral collaboration is the right direction to go to tackle the dramatic problems of the present times, or at least some of them. It is time to apply the famous phrase attributed to Machiavelli, “never miss the occasion of a crisis”, and certainly, we are in multiple ones.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Greco D, Palumbo F, Martino MP et al. (2008) Stewardship and governance in decentralised health systems: an Italian case study. Italian Ministry of Labour, Health and Social Policy, Rome.

Rhodes RAW (1997) Understanding governance: policy networks, governance, reflexivity, and accountability. Buckingham Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 9780335197279.