Summary: With a rapidly growing older population, effective care for ageing patients will require healthcare stakeholders to collaborate in managing the whole health of these patients.

Throughout the world, but especially in Europe and Northern America, the population is ageing at an alarming rate. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs estimates that by 2050, older persons (aged 60 or older) will account for 35% of the population in Europe, and more of these persons are living independently than ever before (United Nations 2017).

These predictions should serve as a call to action for healthcare stakeholders. The importance of managing the whole health of ageing citizens will continue to skyrocket, and that effort will require commitment and cooperation from healthcare providers, healthcare IT vendors, government leaders, and others.

My KLAS Research colleagues and I have interviewed thousands of healthcare leaders about their software tools. These providers have taught us which tools and practices yield the best outcomes and which technologies need the most improvements. With this data in mind, I would encourage healthcare organisations to do the following in order to effectively help the ageing population:

- Partner with your vendor(s) on a solid population health management strategy.

- Take full advantage of remote patient monitoring tools; and

- Increase the focus on interoperability between acute, primary, and post–acute care facilities.

Partnership in Population Health Management

Healthcare stakeholders understand that there is no easy way to reduce the number of health crises that send patients to the hospital. The best tactic for many healthcare organisations is to focus on the whole health of particular groups of patients, typically high-risk patients such as the ageing. In other words, these provider organisations create population health management strategies.

Population health IT includes tools for data aggregation, data analysis, care coordination, finances and administration, patient and family engagement, clinician engagement, and more (KLAS Research 2016). Population health management could be defined as the coordinated application of population health IT tools. Effective population health management can improve and preserve the health of the ageing population by increasing the quality and value of care.

In a 2018 KLAS study on population health management, participants’ responses showed that “vendor partnership and guidance are the x factors provider organisations need to drive success” (Hunter and Warburton 2018). The vendors who received higher scores on questions related to their partnering efforts tended to receive higher scores on their products. This was probably because the providers who received more vendor help and training could use the tools more effectively. One study participant stated:

“[Our vendor] does a great job of optimising our available functionality. When we first rolled out the product, [our vendor] made themselves available to do in-person training. Our facilities are spread over a large area, and [our vendor] still made themselves available for in-person training at each of our facilities. [Our vendor] also made follow-up calls to make sure that they understood things, and they offered web-based training for anyone who might need it. [Our vendor] was able to tailor how they gave assistance so that the assistance made the most sense to our users. They spent a lot of time with our users” (Hunter and Warburton 2018).

Other happy customers described vendors who meet with provider organisations weekly, include needed functionality on transparent road maps, and work with the provider organisations toward the same goals. In short, providers with engaged population health vendors are able to do more for their patients.

This data shows how much responsibility population health vendors bear. But what can provider leaders do if they aren’t satisfied with the relations with their vendor? First, the provider organisation should confirm that both parties share a vision. If not, considering a different vendor might be beneficial. Once a vision has been agreed upon, provider leaders can invite the vendor to participate in conversations about population health management and the respective parties’ road maps. The parties must also agree on their individual responsibilities and set up an effective feedback mechanism.

Remote Patient Monitoring

Ageing patients are easily the most expensive ones. One reason for this is that they tend to have the most chronic health conditions. 75% of the United States’ healthcare spending goes to treating chronic conditions, and 77% of older patients have at least two of them (National Council on Ageing 2018).

Most healthcare organisations already know that managing patients with chronic conditions is key to reducing admissions to hospitals and long-term care facilities. But relatively few health systems have harnessed the power of remote patient monitoring (RPM) technology.

In 2018, KLAS Research partnered with the American Telemedicine Association to complete and publish a report on RPM; providers from 25 healthcare organisations were interviewed about their RPM software. We found that RPM tools have become indispensable to many providers, particularly those caring for patients (including older patients) who have chronic conditions (Sharp and Buckley 2018).

With RPM technology, patient’s health data is digitally collected and sent to healthcare providers, who can then track and assess the data. Customisable alerts let caregivers know when the patient needs attention. Some of the most advanced RPM software also offers disease-specific care plans that can be tailored to the individual patient. These capabilities have become favourites of healthcare providers and can save many trips to hospitals and other facilities.

Furthermore, a number of healthcare IT vendors are adding patient-education content, reminder functionality, and communication tools to their RPM software. Many patients can use the software for video conferences. Instead of travelling for an office visit, a patient can participate in a video call with their doctor and maybe even loop in a family member or other caregiver to the same call. RPM software can also cue patients to take medications, complete periodic surveys, or do other things to preserve their health.

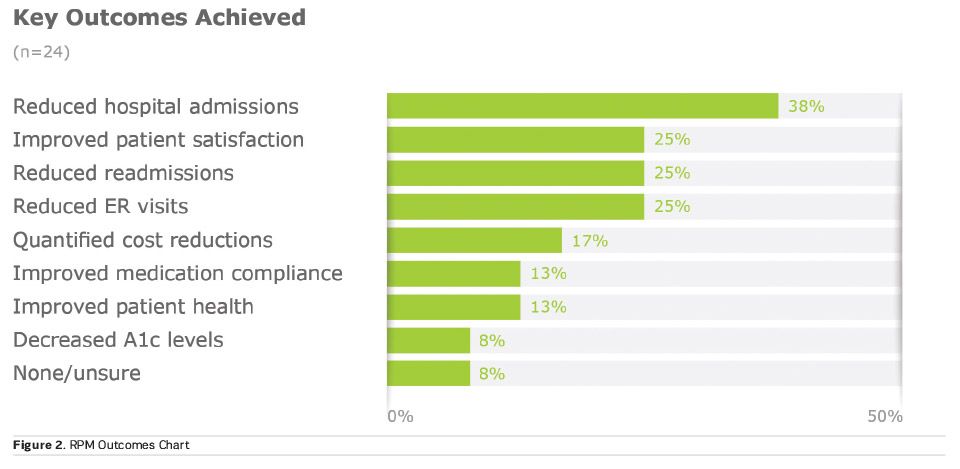

The following excerpt and chart from the report illustrate RPM technology’s potential for good:

“The majority of study participants are very pleased with the success of their RPM programs. Most have achieved measurable outcomes, particularly when it comes to keeping patients out of the hospital (ie admits, re-admits, and ER visits). Even those earliest in their RPM journeys share anecdotal victories, and only a few hesitate to call their efforts a success—not because of failure, but rather because of blurred lines between vendor monitoring and their own outreach work. Heart disease and COPD are the leading use cases, but organisations are branching out to less acute chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension" (Sharp and Buckley 2018).

Of course, RPM software is no silver bullet; stakeholders will need a few years to hone this new technology and related best practices. However, vendors are beginning to offer pay-as-you go models, value-added software, and vendor-managed logistics that are allowing more providers to make use of RPM tools. Even in this development phase, RPM software can allow providers to keep an eye on their high-risk patients, encourage family involvement, and help keep ageing patients healthy at home.

Increasingly Necessary Interoperability

Certain small victories in interoperability have been achieved in recent years. However, most healthcare organisations still have a long way to travel before achieving the ideal level of interoperability. KLAS Research’s 2018 report on the UK National Health Service (NHS) interoperability found that “even those NHS organisations with full integration don’t meet all clinician needs since their use cases are limited to ingesting results or transferring data from one GP to another who uses the same supplier” (Goff and Christensen 2018).

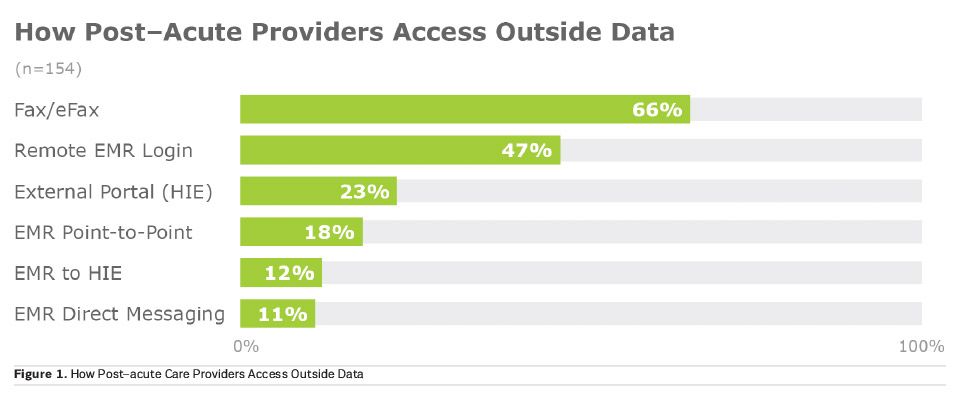

The post–acute space is falling particularly behind. Because post–acute care is less urgent than acute care, interoperability solutions for post–acute facilities receive less attention and funding than the solutions for hospitals. This means the ageing population doesn’t receive as many interoperability benefits as they should. As seen in a chart from a recent KLAS Research report on post–acute interoperability, most providers in the post–acute space (which includes the elderly-dominated long-term care) still rely heavily on faxing (Bermudez and Buckley 2018).

To be fair, faxing is quite convenient for many of the task-oriented providers at long-term care facilities. However, the industry is heading in the direction of normalised, integrated data from many sources, and as the older population grows, the importance of being able to share these patients’ health data digitally will grow as well.

To achieve the kind of interoperability that patients need, several roadblocks will need to be removed or circumvented. The first may be that too many providers—particularly in the post–acute care space—don’t know much about their interoperability tools. KLAS Research has found that “even leadership at post–acute care organisations regularly expressed uncertainty about what Electronic Medical Record-based interoperability tools they might or might not be using—a clear sign that vendors can improve communication around this important topic” (Bermudez and Buckley 2018).

Another barrier is, of course, money. Long-term care and home health organisations have notoriously low business margins and often can’t afford the high prices that Electronic Patient Record (EPR) vendors have traditionally charged for interoperability features. Vendors are beginning to abandon these traditional fees, but that change must be solidified.

The speed at which interoperability spreads will depend heavily on EPR vendors. If EPR vendors want their customers to be successful, they must offer affordable interoperability solutions that are easy to use, help providers understand the benefits of interoperability, urge customers to fully adopt the functionality, and provide thorough training for the clinicians.

Provider organisations that aren’t seeing such efforts from their EPR vendors can push for change. If provider leaders stay aware of what is happening with interoperability in the industry, they can use that knowledge as leverage with their vendors. In addition, provider leaders can make sure that their own organisation and their EPR vendor each have interoperability on their road map and that both sides have agreed on a way to achieve interoperability together.

As stakeholders continue to work together toward greater interoperability, particularly in the post-acute care world, they will create a better world for all parties, including the ageing population. Clinicians will have access to enough data to focus on the whole health of their patients, and patients will be spared from many clinical errors and receive quicker diagnoses and care.

Conclusion

The ageing population needs healthcare IT vendors, healthcare providers, and government leaders to understand the post–acute care space and how to care for the whole health of a patient. The following are steps I would encourage these stakeholders to take in order to help older patients:

- EPR and Population Health Vendors: Get to know your customers and form close relationships with them. Share your road map and make sure your goals are aligned with your customers’. Teach customers how to leverage all of their tools in a way that can help them establish a longitudinal record.

- Healthcare Providers: Implement and use tools (such as RPM software) that can help you be proactive in caring for your patients. Get patients and their family members involved and use the appropriate tools. Collaborate with your EPR and population health vendors; and

- Government Leaders: Use your influence to encourage interoperability, technology development, and certification processes for tools such as EPRs. Create a landscape of financial support and reimbursements that will allow healthcare providers to invest in effective tools and best practices.

Key Points

- Provider organisations will find the most success in population health management strategies when they partner with engaged vendors.

- Remote patient monitoring is reducing hospital-admittance rates and helping provider organisations engage their ageing patients.

- Interoperability between acute and post–acute facilities will become increasingly needed as the older population increases.

- Stakeholders must work toward ambitious interoperability goals in order to ensure progress.