HealthManagement, Volume 16 - Issue 4, 2016

For its fifth Deep Dive analysis of a patient safety topic,

ECRI Institute PSO selected patient identification. Safe patient care starts

with delivering the intended interventions to the right person. Yet, the risk

of wrong-patient errors is ever-present for the multitude of patient encounters

occurring daily in healthcare settings.

Many patient identification mistakes are caught before care is provided, but reports submitted to ECRI Institute PSO illustrate that others do reach the patient, sometimes with potentially fatal consequences.

In addition to their potential to cause serious harm, patient identification errors are particularly troublesome for a number of other reasons, including:

- Most, if not all, wrong-patient errors are preventable.

- Incorrect patient identification can occur during multiple

procedures and processes, including but not limited to patient registration,

electronic data entry and transfer, medication administration, medical and surgical

interventions, blood transfusions, diagnostic testing, patient monitoring, and

emergency care.

- Patient identification mistakes can occur in every healthcare

setting, from hospitals and nursing homes to physician offices and pharmacies.

- No one on the patient’s healthcare team is immune from

making a wrong-patient error. Mistakes have been made by physicians, nurses,

lab technicians, pharmacists, transporters, and others.

- Many patient identification errors affect at least two people.

For example, when a patient receives a medication intended for another patient,

both patients— the one who received the wrong medication and the one whose

medication was omitted—can be harmed.

Given that correct patient identification is fundamental to safe care, the Joint Commission has made accurate patient identification one of its National Patient Safety Goals since 2003 when the first set of goals went into effect. The Joint Commission is not alone in advocating for safe practices to ensure correct patient identification. The National Quality Forum lists wrongpatient mistakes as serious reportable events and also considers patient identification as a high-priority area for measuring health information technology (IT) safety.

Even the media has called attention to the issue. Of the 25

“shocking medical mistakes” listed by cable news network CNN in 2015, at least

6 involved wrong-patient errors. Despite the attention given to correct patient

identification, mistakes continue to occur.

See Also: ECRI - Automated External Defibrillators

Understanding Patient Identification

ECRI Institute PSO uses the following definition of “patient identification,” adapted from the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care:

Patient identification is the process of correctly matching a patient to appropriately intended interventions and communicating information about the patient’s identity accurately and reliably throughout the continuum of care.

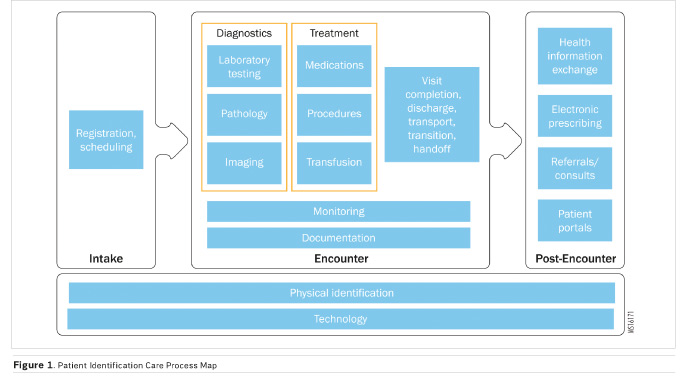

As shown in Figure 1, patient identification occurs throughout the patient’s encounter in the care continuum. ECRI Institute PSO developed a care process map to conceptualise a patient’s movement through any healthcare setting and to show key points when patient identification is necessary.

The patient’s care process involves three distinct phases for analysing patient identification events:

- Intake (ie, registration, scheduling)

- Clinical encounter (eg, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, discharge/visit

completion)

- Post-encounter (eg, referrals, health information exchanges,

electronic prescribing)

Underlying all three phases is physical identification of the patient using at least two patient identifiers as well as various technologies with features that facilitate patient identification. These technologies include electronic health records (EHR s), computerised provider order entry (CPOE ) systems, barcode scanners, physiologic monitors, electronic prescribing capability, and more. While the inappropriate use of these technologies can contribute to wrong patient errors, when used properly these systems also play a role in preventing identification mistakes.

What ECRI Institute PSO Found

For its Deep Dive on patient identification events, ECRI Institute PSO analysed 7,613 events submitted by 181 healthcare organisations. ECRI Institute PSO conducted a keyword search of its event report database to find events involving patient identification occurring over the 32-month period from January 2013 through August 2015. The term “event” includes near-miss events (events that are detected before reaching the patient) as well as events that reach the patient, some of which cause harm. We also asked member organisations and partner PSO s to submit at least 10 events related to patient identification during a six-week call to action (June 18 to July 31, 2015). We collected 10,915 events from these initiatives.

ECRI Institute PSO analysts individually classified each of the events using a unique taxonomy developed by the PSO for analysing patient identification events. Of the 10,915 events, the analysts eliminated 3,302 reports that were not wrong-patient events and classified the remaining 7,613 events using the patient identification event taxonomy.

Sample Wrong-Patient

Events from ECRI Institute PSO’s Database

- Medical-surgical

unit: A patient in cardiac arrest was mistakenly not resuscitated because

the care team pulled up the wrong patient’s record and adhered to a

do-not-resuscitate order.

- Surgery: A

cardiac clearance meant for a different patient was given to a patient who

previously had an abnormal electrocardiogram. The patient underwent surgery and

was found unresponsive in his hospital room the next day.

- Dietary: The

wrong meal tray was given to a patient with a nasogastric tube who was not to

receive any food or fluids orally. The patient attempted to eat the food and

choked.

- Diagnostic imaging:

The wrong patient was taken to the radiology department for a magnetic

resonance imaging exam with general anaesthesia. The patient was intubated and

sedated before the error was caught.

- Pharmacy: A

patient received a different patient’s hypertensive medication, at 10 times the

intended dose. The patient was admitted to intensive care for hypotension.

- Maternity ward:

An infant received another infant’s breastmilk. The mother who produced the

breastmilk was infected with the hepatitis B virus, so the infant had to be

treated with hepatitis B immune globulin.

- Doctor’s office:

The wrong patient was marked as deceased in the doctor’s office’s electronic

health record. All her outstanding appointments were automatically cancelled.

When the patient arrived for a previously scheduled appointment, she was not

happy that all her appointments had been cancelled.

- Eye clinic: Two

patients with the same first name were scheduled for cataract surgery. The

wrong patient was brought into the operating room and received the lens implant

intended for the other patient.

- Nursing home: A

patient from a nursing home was scheduled for a computed tomography scan at an

affiliated hospital. The wrong patient (who had a similar name) was picked up

from the nursing home, taken to the hospital, and underwent the exam.

The taxonomy assigns a failure mode associated with each event. Some of the events had more than one failure mode, resulting in 7,740 failures identified from the 7,613 events.

Examples of wrong-patient events submitted to ECRI Institute PSO by healthcare organisations are listed in “Sample Wrong-Patient Events.” The events occurred in a wide range of settings.

The events describe an array of factors that can contribute to wrong-patient errors, such as the following:

- Admitting a patient under another patient’s medical record

or creating duplicate records at registration

- Using a room number or bed assignment to identify a

patient who has been moved to a different room or bed

- Asking a patient to confirm his or her name (“Are you Mr.

X?”) instead of asking the patient to state his or her name (“Tell me your

name.”)

- Pulling the medical record of a patient with a name similar

to that of the intended patient

- Entering orders in the wrong patient’s chart

- Asking about the patient’s identity without using two

acceptable identifiers or checking the patient’s identification band

- Administering a patient’s medications before confirming the

patient’s identity with barcode scanning

- Retaining previously recorded patient demographic data

when a new patient is connected to physiologic monitoring equipment, or

matching portable telemetry equipment with the wrong patient

- Relying on patients with impaired ability to confirm their

identifying information

Analysis

Among the results from the analysis, ECRI Institute PSO found the following:

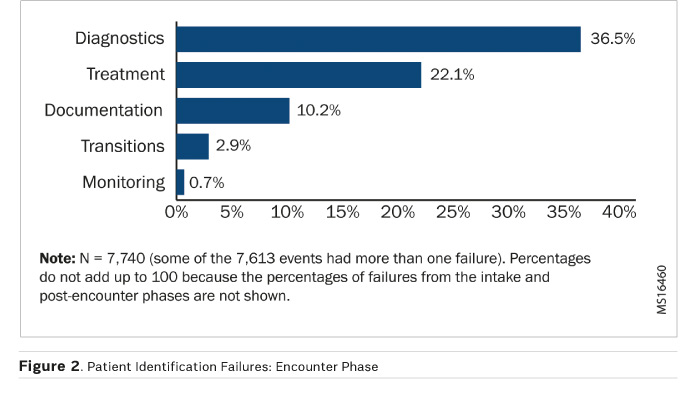

- The majority of the failures (72.3%) occurred during patient

encounters; another 12.6% occurred during the intake process. Very few failures

were identified during the post-encounter phase.

- More than half of the failures involved either diagnostic procedures

(2,824 or 36.5%) or treatment (1,710 or 22.1%). Diagnostic procedures cover

laboratory medicine, pathology, and diagnostic imaging. Treatment covers

medications, procedures, and transfusions. (See Figure 2.)

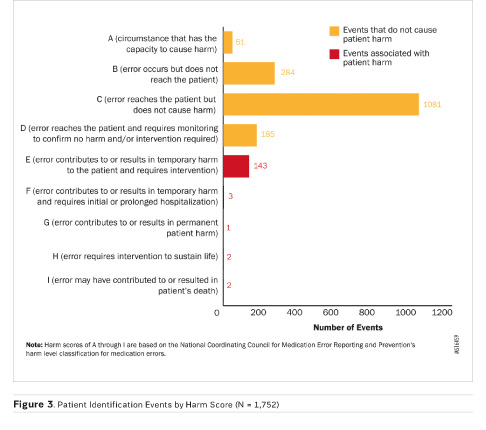

- The majority of the events for which a harm score was provided

were caught before they caused any harm (1,601 of 1,752 events, or 91.4%). (See

Figure 3.)

- The two wrong-patient events associated with patient

deaths involved documentation failures; in one event, the wrong patient record

was accessed, and in the other event, the wrong patient’s documentation was

used to give another patient clearance for surgery.

- Wrong-patient events involving physical identification of

patients constituted about 15% of all the failures identified; most of these

events fell into three categories: wristband missing, patient identity not

verified, or wristband identifiers incorrect.

- Almost 15% of events (1,148) were associated with

technology contributing to patient identification errors.

Key Recommendations

Leadership

- Communicate to staff the expectation that patient identification

is essential for safe care and is an organisational priority.

- Ask questions about the organisation’s patient

identification practices and experiences (eg, what adverse events and claims

activity at the organisation are related to patient identification processes?)

to identify strengths and opportunities for improvement.

- Provide support for the organisation’s patient

identification improvement initiatives to mobilise the many stakeholders who

contribute to the efforts and to provide the necessary resources and staff to

support the initiatives.

Policies and Procedures

- Examine the organisation’s work processes—for example,

conduct a failure mode and effects analysis—to uncover any latent system-wide

problems with patient identification; the Deep Dive analysis found that lapses

in adhering to an organisation’s patient identification policy were a

contributing factor for events that led to patient harm.

- Adopt a standardised protocol to verify a patient’s identity;

ensure that the policy and procedures spell out the details for patient

identification (eg, which identifiers to use and when).

- Ensure that all staff who have duties relating to patient

identification receive training about the policy and the importance of adhering

to the procedures for patient identification.

- Share with staff wrong-patient events that have occurred

at the facility to drive home the message that patient identification errors

can happen and may have serious consequences.

Patient and Family Engagement

- Engage patients and their family members in patient identification

by explaining the purpose of the organisation’s approach to patient

identification and emphasising patients’ and family members’ roles in ensuring

correct identification.

- Encourage patients to speak up if staff do not ask for

patient identifiers or if they are approached for unexpected tests or

treatments.

- Enable patients to view and access information about their

hospital admission and physician visits from a secure patient portal. Ask

patients to speak up if information is missing or incorrect; errors may be the

result of a patient mix-up.

Patient Registration

- Support registration staff with clearly defined policies and

procedures for the registration process; otherwise, incorrect patient

information introduced at registration can compromise quality of care

throughout the patient’s course of treatment if the mistakes are not identified

and corrected.

- Consider supplementing the registration process with biometric

methods to improve patient identification.

- Foster a work environment that supports registration staff

and values their contribution to patient safety through accurate patient

identification.

- Implement a quality assurance plan using metrics such as

duplicate record and record overlay rates to monitor the patient registration

process, and share the results with registration staff.

- Monitor various public and private initiatives to improve

patient record matching and to promote information exchange between

organisations.

Standardise and Simplify

- Adopt standard features for patient identification bands

(eg, information display, location of patient name) to improve usability and

readability.

- Ensure that the Joint Commission Universal Protocol to

prevent wrong-person procedures, including the time-out protocol, is uniformly

applied and consistently used by all providers.

- Provide a list of invasive procedures performed outside of

the operating room (eg, biopsy, injections into a joint space or body cavity,

insertion of central vascular access device) that require application of the

Universal Protocol to prevent wrong patient errors.

Technology

- Ensure the safe use of patient care technology to prevent

wrong-patient mistakes; adopt measures to prevent patient mismatches that occur

when patient information is incorrectly recorded in bedside equipment, such as

point-of-care tests and physiologic monitors.

- Consider technology, such as barcoding or radiofrequency identification,

to support patient identification, while addressing its limitations.

- Adopt a well-defined approach to evaluate and implement safety-enhancing

technologies and to monitor their use after implementation to achieve their full

benefit; otherwise, technology can contribute to errors if it is poorly designed,

staff do not know how to use it correctly or optimally, or staff perceive it as

interfering with their workload.

- Incorporate strategies to improve the usability of health

IT systems and to minimise the risk of human error; incomplete approaches to

the planning, implementation, and ongoing use of health IT can lead to

unintended consequences such as mistakes in managing patient records and data.

- Clearly display attributes used in patient identification (eg,

last name, first name, date of birth, calculated age, gender, medical record

number) across all health IT applications, and include a banner or header with

at least two patient identifiers in every display, view, or screen in the

electronic health record.

- Display patient names on adjacent lines of a computer screen

in a visually distinct manner to reduce the likelihood of selecting the wrong

patient name.

- Harness the functions of health IT to support patient verification

processes (eg, use patient verification decision support; embed patient

photographs in records). Event Reporting and Response

- Foster a culture in which staff recognise the importance of

reporting events and near misses involving identification errors as part of the

organisation’s overall commitment to safety.

- Analyse events identified by incident reporting in a structured,

step-by-step investigation to identify the process breakdowns that cause people

to make errors.

- Use the information learned from event reports to improve

patient identification and provide feedback to staff on improvements that are

made as a result of their event reporting.

- Conduct proactive risk assessments to uncover latent system-wide

problems contributing to wrong-patient errors, as well as problems that are

specific to particular departments or settings, such as nurseries, emergency departments,

or behavioral healthcare settings.

- Conduct periodic audits of patient identification processes

(including electronic processes) to monitor

- and detect trends in compliance.

- Provide reports to senior leaders and board members on the effectiveness of patient

identification initiatives to sustain the organisation’s commitment in this

area.

Conclusion

ECRI Institute PSO ’s Deep Dive analysis of wrong-patient events shows that the risk of errors is ever-present for the multitude of patient encounters occurring daily in healthcare settings.

These events occur during multiple procedures and processes and can involve nearly anyone on the patient’s healthcare team. As a result, no single strategy can prevent these events; instead, organisations must adopt a multipronged approach to prevent wrong-patient mistakes.

The report discusses patient identification strategies involving policies and procedures, registration, standardisation, technology, patient and family engagement, and event reporting and response. Crucial to the success of these strategies is the role of senior leadership in supporting initiatives to improve patient identification and to ban what one researcher calls a “culture of low expectations.” Patient identification must occur with every encounter and procedure. Staff cannot become lax and adopt unsafe habits by skipping patient identification. The leadership team must clearly communicate to staff that following patient identification practices is a top priority.

Several ECRI Institute PSO members and collaborating organisations shared their stories for this report about wrong-patient events and the steps they took to improve patient identification. Their experience makes clear that wrong-patient errors can be prevented, starting with an organisational commitment to improve. ECRI Institute PSO encourages all healthcare organisations to consider the recommendations of this report in order to deliver safe, high-quality patient care.

ECR I Institute, a nonprofit organisation, dedicates itself to

bringing the discipline of applied scientific research in healthcare to uncover

he best approaches to improving patient care. As pioneers in this science for

nearly 45 years, ECR I Institute marries experience and independence with the

objectivity of evidence-based research.

ECR I Institute, a nonprofit organisation, dedicates itself to

bringing the discipline of applied scientific research in healthcare to uncover

he best approaches to improving patient care. As pioneers in this science for

nearly 45 years, ECR I Institute marries experience and independence with the

objectivity of evidence-based research.

ECR I’s focus is medical device technology, healthcare risk and quality management, and health technology assessment. It provides information services and technical assistance to more than 5,000 hospitals, healthcare organisations, ministries of health, government and planning agencies, voluntary sector organisations and accrediting agencies worldwide. Its databases (over 30), publications, information services and technical assistance services set the standard for the healthcare community.

More than 5,000 healthcare organisations worldwide rely on ECR I Institute’s expertise in patient safety improvement, risk and quality management, healthcare processes, devices, procedures and drug technology. ECR I Institute is one of only a handful of organisations designated as both a Collaborating Centre of the World Health Organization and an evidence-based practice centre by the US Agency for healthcare research and quality in Europe. For more information, visit ecri.org.uk