HealthManagement, Volume 21 - Issue 5, 2021

Case Study: Amyloidosis on Portal of Mayo Clinic et al.

In the age of constantly accessible Internet, would-be patients and healthcare professionals often “Google it” when faced with an ailment or an unusual symptom or condition. In order to test how reliable and consistent the information is that is found there, we conducted a review of several Internet-based information sources which combine symptoms and underlying causes (diagnoses, diseases). As our findings show serious inconsistencies in symptoms/diseases mapping, we propose solutions for how to remedy this issue and suggest ways to make medical information on the Internet more secure and useful for both patients and healthcare providers.

Key Points

- Integral symptoms/diagnoses database must be established.

- Wordings of all terms must be checked and corrected (synchronised), preferably by using some standard classification or nomenclature.

- Both views should “look” at the same information source, where appropriate IT solutions are to be implemented aimed at ensuring information quality and security.

- “Symptoms’ view” has priority to be corrected, due to its prevailing importance over “diagnosis/condition view”.

- Symptoms feed directly from patients after they have a confirmed diagnosis is operationally advantageous.

- All portals must establish the feedback feature where users can report deficiencies experienced.

Introduction

This research was induced by a medical case which began when the patient reported severe unexplained weight loss. This was followed by a long diagnostic process, conducted in very different directions, including colonoscopies and major surgery on the patient’s bowels after suspicion of cancer. This final procedure and following histopathology finding turned out to be negative. After the patient experienced renal failure, a kidney biopsy was performed with subsequent complications. This specimen revealed amyloidosis as the diagnoses and because of the known association to multiple myeloma, the patient was quickly forwarded to haematology. Multiple myeloma was subsequently diagnosed, which was the underlying cause of secondary amyloidosis. As a result of the belated diagnosis and delayed start of treatment of the patient (nearly 8 months after detecting symptoms), there was severe and partially non recoverable damage to multiple organs.

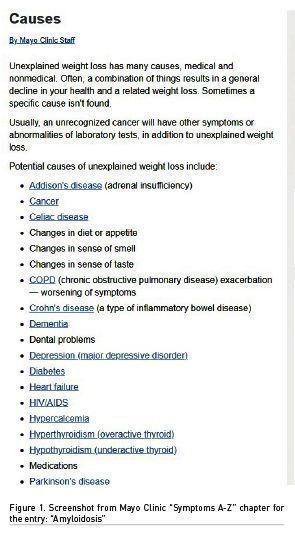

The delay in diagnosis and treatment was due in large part to the lack of association of the initial symptom and the condition. We searched possible causes of unexplained weight loss, consulting many online sources. The base for the review was our experience with the Mayo Clinic portal for patients (MayoClinic.org 2021). When we searched specifically for causes of unexplained weight loss, 23 possible causes of this symptom were listed; unfortunately amyloidosis was NOT mentioned at all (Figure 1.)

It was quickly found that the way to view to this information via symptoms is not consistent with that of the information found via disease and conditions, where in one symptom description page all related diseases (diagnoses) should be listed. In order to illustrate the inconsistencies, this paper is focused on the association between: diagnosis “Amyloidosis” and symptom “Unexpected weight loss”.

The symptom mentioned can be seen in “diseases view” (diagnosis “Amyloidosis”). The opposite “symptoms view” for “weight loss” does not yield diagnosis “amyloidosis” in the list of dozens of diagnoses listed. In the Mayo Clinic portal, this inconsistency is common practice: the same applies for “amyloidosis” also for the symptom “leg swelling” etc. In addition, inconsistency in naming the symptoms (as well as other entities) was detected. “Symptom Checker” page on the Mayo Clinic website offers very poor information with only 28 symptoms listed in total.

It is understandable that all symptoms cannot be mapped completely with all associated diagnoses, especially if a rare disease is concerned, such as secondary amyloidosis. However, after obtaining the respective diagnosis, the Mayo Clinic source was consulted again, with the result depicted in Figure 2.

The search for “Amyloidosis” yielded the article “What is amyloidosis and 10 signs you might have it” published on the Mayo Clinic website (Sparks 2019), where “unintentional weight loss”, is listed as the third most frequent/important symptom:

“Unintentional, significant weight loss. If you’re losing protein from your blood, you may lose your appetite and, as a result, lose weight without trying. If amyloidosis affects your digestive system, it can also affect your ability to digest your food and absorb nutrients. It’s common to lose 20 to 25 pounds.”

In the article, the author Dr Dana Sparks rightfully directs patients as follows: “Many of these signs and symptoms may be caused by other conditions. But if you experience any of them, talk with your healthcare provider about whether they might be caused by amyloidosis.“

Materials and Methods

Based on the patient case presented in the introduction, research was made on the following internet portals/sites/platforms which render the “symptoms checker” service or similar:

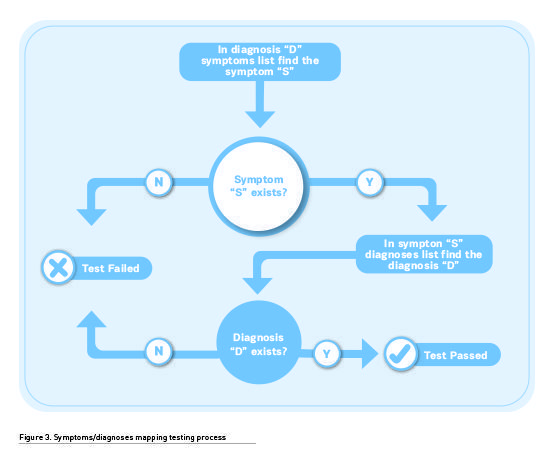

Material mentioned was analysed according to the aim of this paper to map between symptoms and diagnoses. This analysis was made in both directions: First the symptoms were found in the diagnosis (disease) description, and subsequently these symptoms descriptions were checked against diagnoses. This “test” resulted in “passed” if the same diagnosis was found in both searches. Analysis process is shown in Figure 3.

While the main focus of the analysis was on the symptom and final diagnosis of the case in discussion (unintentional weight loss and amyloidosis), some lateral symptom/diagnosis pairs were also examined, with the aim to find evidence of other general inconsistencies.

Results

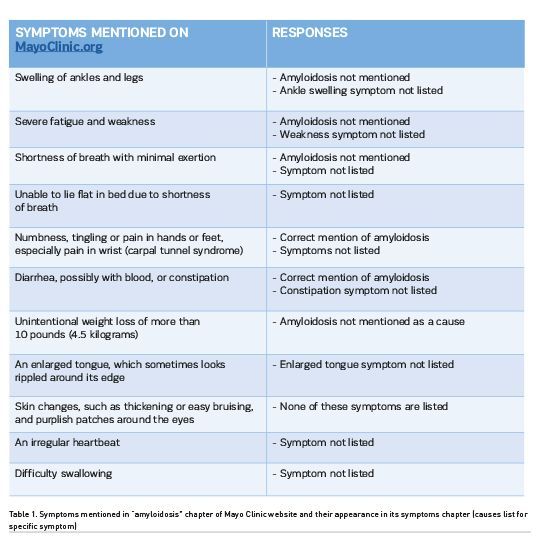

According to the materials and methods described, here the results are presented, for each and every web page examined and tested against consistency of symptoms/diagnoses mapping. From Table 1, we see that there are several types of inconsistencies. Either the diagnosis is not mentioned in the symptom’s description page, or the symptom mentioned in the diagnosis page is not existent in the symptoms list. The wording of symptoms is also inconsistent. Here we observe not less than five different wordings:

- “Unintentional weight loss” (in amyloidosis chapter)

- “Unexpected weight loss” (in symptoms list entry)

- “Unintentional, significant weight loss” (in Dana Sparks’ paper)

- “Weight loss” (in sarcoidosis chapter, even directing on “Obesity”)

- “Losing weight without trying“ (Lung cancer chapter)

Of course, neither “weight loss” nor “losing weight without trying” can be found in the symptoms list on Mayo Clinic portal. This means that sarcoidosis and lung cancer also cannot be added to the differential diagnoses list searching with such wording via symptoms. In addition, when we look for “weight loss” in the Mayo Clinic symptoms list, we also obtain a misleading result: “Weight loss (See: Obesity)”. Given these numerous issues, it is unclear why the Mayo Clinic has not implemented systematic quality control of their health and medical information intended for the broader public.

Proposed Solutions

In this situation, best practice would be to adhere to some standard, for instance ICD-10, R-classification. There are more than 700 hundred symptoms presented in a scrutinised manner. Focussing on the instance researched – “weight loss” – ICD-10-R uses standard wording “abnormal weight loss”. It is up to medical experts to evaluate whether the naming in Mayo Clinic portal for this instance corresponds fully to this standard symptom wording, but the final aim is to have it appear consistently in different parts of website.

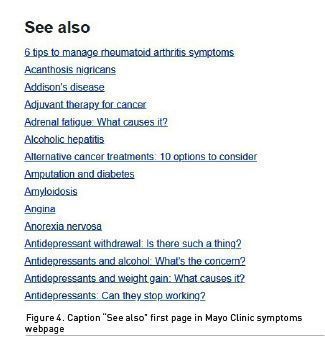

Here we want to mention one more deficiency of Mayo Clinic symptoms presentation. It relates to the “See also” caption, which we can see in the “Causes” table, as depicted in Figure 4.

As we can see, amyloidosis is listed here, but is among 300 other different symptoms, diagnoses, laboratory tests, conditions and other medical terms. Finding “amyloidosis” on the first page of this list is pure luck, because it begins with the letter “A”. This list is very questionable because of the example “Acanthosis nigricus”, which has, according to its description in the Mayo Clinic portal, only one symptom is mentioned and it has nothing to do with “Unintentional weight loss”. The same applies also for “angina” and a majority of the other terms listed here. Opposite inconsistency is observed for “sarcoidosis”: despite the fact that in the disease description “weight loss” is mentioned, in the symptom “unexpected weight loss” lists for “Causes” and “See also” this diagnosis does not appear. This “See also” list is huge and irrelevant and represents a kind of “information noise” that can only confuse the reader.

Amyloidosis is not the only diagnosis which demonstrates inconsistency in searching it through the symptoms list. The same is observed also in the case of very common diseases, such as GERD (Gastroesophageal reflux disease). One of the symptoms mentioned here is “Regurgitation of food or sour liquid”, however neither symptom nor any of its keywords was mentioned in the symptoms list.

There are also numerous instances of such inconsistencies in symptom/diagnosis “intersections”. As an example, the field of neurology was also examined, for a common disease such as multiple sclerosis. In the disease chapter, the symptom “tremor” was mentioned, while in the symptoms chapter, such symptom is not listed at all. Another manifestation of inconsistency for the diagnosis “multiple sclerosis” is the symptom “dizziness”. This common symptom was mentioned in the diagnosis chapter, but in the list of diagnoses stated as the cause of this symptom, it is not noted at all.

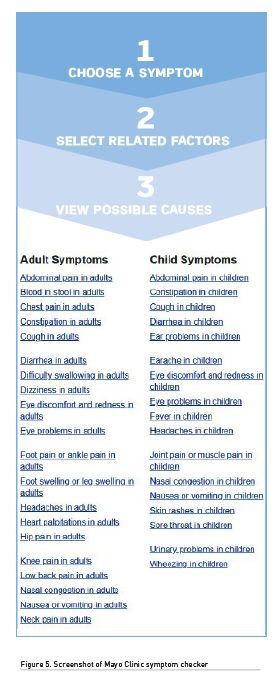

On the Mayo Clinic website, we also found the service called “Symptom checker”. Unfortunately, the content of this service is extremely poor. It consists out of only 28 different symptoms for adults, as can be seen on Figure 5. On the other hand, in the general symptoms table, there are some 300 different symptoms, whereas there are about 700 in ICD-10.

Similar inconsistencies were observed in another health information source – the NHS. On the amyloidosis webpage we examined the symptom “weight loss”. In the disease description, the symptom “loss of appetite” was mentioned, but when looking backwards in this symptom page, amyloidosis was not mentioned. In addition, this symptom naming is not recognised by ICD-10 at all.

On this portal similar inconsistency was observed related to “Carpal tunnel syndrome”, which was mentioned among “other symptoms” of amyloidosis. But if one goes to the symptoms page, there is no mentioning of amyloidosis.

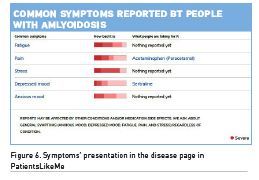

Another source examined on the issue of consistency of medical information is the portal PatientsLikeMe. A platform with a data feed (also) from patients can be very useful for building a proper database of symptom/diagnosis associations. On the PatientsLikeMe portal, this could be implemented rather than the current one depicted in Figure 6.

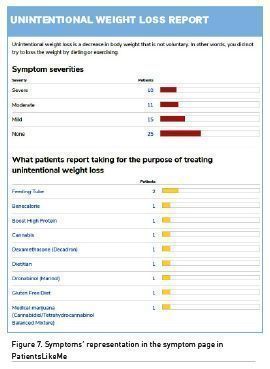

The PatientsLikeMe symptoms’ page presented in Figure 7. is very questionable, as it can direct the patient to take some steps by him/herself, instead of offering information about possible causes of this symptom. This page neglects a very straightforward diagnostic process, where first two steps are as follows:

- Gather all information about the patient and create a symptoms list. The list can be in writing or in the clinician’s head.

- List all possible causes (candidate conditions) for the symptoms.

This “list of all possible causes” or “candidate conditions” is what is missing in all of the internet services researched. Furthermore, after these first two steps, clinicians must then prioritise what should happen and then eliminate or confirm diagnosis, mostly based on laboratory tests and imaging procedures. The fifth and sixth steps are finally the diagnosis and therapy. (en.wikipedia.org 2021)

On portals such as PatientsLikeMe, the middle steps are neglected, and the patient gets information about how some other patient treated, without experiencing their own actual diagnosis.

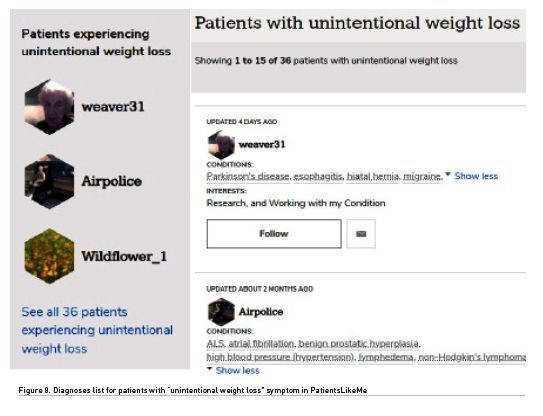

The architecture of PatientsLikeMe is deficient despite the fact that this website has complete symptoms and diagnoses information from patients, as shown in Figure 8.

Unlike the Mayo Clinic portal, PatientsLikeMe does not have a “symptoms view”, which could support medical doctors in a differential diagnosis search. This is despite the availability of such information in their database and the best practice of presenting information in a reliable way, meaning with integrity and transparency.

Discussion

Authors tried to get feedback about the main points set out in this paper from the medical sources mentioned. Reaction was poor. In addition, several medical experts and end users representing patients were consulted concerning the issue of inconsistencies observed. Within the Croatian Society for Medical Informatics all issues will be discussed further in a forum and these round table conclusions will be presented in separate paper.

In concluding this discussion about the issue researched, medical doctors should answer one very simple question related to the purpose of this research: “Is there any medical reason to mention a symptom in disease description and NOT to mention this very disease in this symptom’s causes list?”

A negative answer denotes the evidence that this issue was worth being researched. A positive answer must also give arguments as to why the information about the symptom in disease webpage is of some value, but the opposite is not.

The success of the diagnostic procedure relies heavily on the importance of clinicians obtaining as much information about the patients’ symptoms as possible, as well as the availability of a complete diagnostic hypothesis list.

Conclusion and Recommendations

There are obvious deficiencies in numerous medical portals which deal with symptoms/diagnoses mapping. In the case study noted, these shortcomings led to a kind of “malpractice” wherein the tissue from biopsy was not tested with Congo red stain for amyloidosis. While this is somewhat understandable because amyloidosis is a really rare disease and the working diagnosis was cancer. However, if the online list of diagnoses associated with “unintentional weight loss” was complete, the pathologist may have considered amyloidosis much sooner, after not finding another diagnosis.

Therefore, all subjects responsible for medical portals are strongly recommended to remove this architectural shortcoming by implementing improvements as follows:

- Integral symptoms/diagnoses database must be established

- Wordings of all terms must be checked and corrected (synchronised), preferably by using some standard classification or nomenclature

- Both views should “look” at the same information source, where appropriate IT solutions are to be implemented aimed at ensuring information quality and security

- “Symptoms’ view” type webpages corrections should be prioritised, as they are highly accessed by patients and more important than other views

- Symptoms feed directly from patients after they have a confirmed diagnosis is advantageous

- All portals must establish the feedback feature where users can report deficiencies experienced

- Links between symptoms and diseases should be presented as a quantitative measure of the “association strength” (in the next improvement phase)

Of course, such long list of suggested actions should be prioritised, “low hanging fruit” principle can be taken into account. In the case we analysed here, elementary information “cell” is the intersection of diagnosis and symptom. It would be a great advantage to state the strength of such an association as in Table 2. e.g. What is the percentage of detected weight loss symptom in diagnosed amyloidosis?

In this exemplary (fiction) case, the symptom/diagnosis can be indicated as follows:

- By the onset of the symptom “unintentional weight loss”, there are 1,23 % cases with diagnosis “amyloidosis” and vice versa.

- By the diagnosis “amyloidosis”, 3,21 % patients reported the symptom “unintentional weight loss”.

Of course, there is considerable work ahead to obtain these figures. Here, we return to the importance of information coding and standard medical terms wording. In the digital era, more information is entered by clicking on the screen rather than by writing free text on white paper. Without dictating how medical doctors will enter data in medical records, another possibility is to promote standard “free text” wording, which can be a posteriori analysed by algorithmic or AI based solutions. This can lead to obtaining a database with data structure, to which a simple model is depicted in Table 2.

The process of gathering data and preparing information should be designed as follows:

- MDs are asked about symptoms observed in diseases from their fields of expertise

- Previous symptom/disease data can be supplemented with patients’ personal experience

- This data is gathered and table diseases/symptoms is formed

- Diagnoses and symptoms have to be structured and named according to some official classification/nomenclature, preferably ICD-10

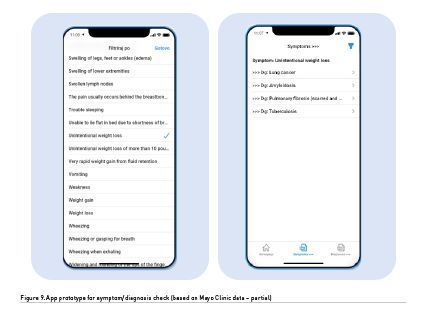

This process is substantially simpler compared to the one obviously used until now, yielding correct information for all groups of stakeholders (patients, medical doctors, students). The lack of values indicating the strength of symptom/diagnosis association should not hinder the efforts for immediate improvement of the systems mentioned. Until such figures will be available, instead of percentage only some kind of “X” in the crossing cell can be checked. This is nothing new, all these data exist in Mayo Clinic portal or other medical resources on the Internet. An example of such service can be seen in this prototype, developed with partial Mayo Clinic data available, and seen in screenshots in Figure 9.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References:

Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR (editors) (2015) Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015 Dec 29. 2, The Diagnostic Process. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338593/ (accessed 5.5.2021)

CDC ICD-10 Index. Chapter: Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00–R99). Available at: icdlist.com/icd-10/index/symptoms-signs-abnormal-clinical-laboratory-findings-not-elsewhere-classified (accessed 5.5.2021)

Kern J, et al. (2021) ‘Declaration on eHealth. 1st Revision’, Bilten Hrvatskog društva za medicinsku informatiku (Online), 27(1), pp. 1-9. Available at: hrcak.srce.hr/253259 (Accessed 5.5.2021)

Mayo Clinic, Amyloidosis description in HEALTH A-Z page. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/amyloidosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353178 (accessed 2.5.2021)

Mayo Clinic Lung cancer description in HEALTH A-Z page. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lung-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20374620 (accessed 7.5.2021)

Mayo Clinic Oesophageal cancer disease symptom page. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/esophageal-cancer/multimedia/esophageal-cancer-infographic/ifg-20442996 (accessed 2.5.2021)

Mayo Clinic Sarcoidosis description in HEALTH A-Z page. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sarcoidosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350358 (accessed 7.5.2021)

Mayo Clinic Symptoms chapter in HEALTH A-Z page. Available at: mayoclinic.org/symptoms (accessed 5.5.2021)

Mayo Clinic Unexplained weight loss symptoms page. Available at: mayoclinic.org/symptoms/unexplained-weight-loss/basics/definition/sym-20050700 (accessed 2.5.2021)

NHS Unintentional weight loss symptom page. Available at: nhs.uk/conditions/unintentional-weight-loss/ (accessed 5.5.2021)

PatientsLikeMe. Available at: patientslikeme.com (accessed 5.5.2021)

Sparks D (2019) What is amyloidosis and 10 signs you might have it. Mayo Clinic; newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/what-is-amyloidosis-and-10-signs-you-might-have-it/ (accessed 2.5.2021)

WebMD Symptoms list. Available at: symptoms.webmd.com/ (accessed 5.5.2021)

Wiki Differential diagnosis description. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Differential_diagnosis (accessed 2.5.2021)