HealthManagement, Volume 25 - Issue 3, 2025

The ageing population faces increasing patient safety risks due to complex care needs, multimorbidities, reduced physiological reserve and often cognitive decline, all managed within fragmented health systems. Common issues such as delirium, falls, pressure ulcers, malnutrition, dehydration, healthcare-associated infection and medication-related harm are often preventable. Ensuring safer, coordinated and patient-centred care requires systemic changes, better training and a strong safety culture across all care settings.

Key Points

- The ageing are at increased risk for adverse events in every clinical setting and are disproportionally affected by unsafe and low-quality care.

- Geriatric syndromes like delirium and falls are common patient safety challenges which are often preventable.

- Polypharmacy increases medication-related harm and adverse drug events in older adults.

- Care is often fragmented with poor coordination across diverse healthcare settings.

- A culture of safety and integrated, patient-centred care is urgently needed.

Introduction

Populations are ageing faster than ever before, while healthcare infrastructures are struggling to keep pace. As people live longer—due to medical advancements and better living conditions—they are also living with more complex health needs. This is not just a trend. It's a global shift with implications on how good quality care is provided to ensure patient safety.

The Ageing Surge

By 2050, the global population of ageing people will surpass 2 billion (WHO). Already, older adults outnumber children under five, and this trend is not limited to high-income countries. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) already have 80% of the world’s older adults—a number set to rise in the next decades (The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2021).

Population ageing is a key driver of the growing disease burden among older adults, significantly reshaping healthcare needs and straining health systems. They are prone to multiple chronic illnesses, comorbidities, disabilities and cognitive decline. Consequently, there is a growing need for specialised care. This necessitates continuous, coordinated support across a broad range of services—from prevention and treatment to rehabilitation and end-of-life care.

Patient Safety: An Overlooked Crisis for the Ageing Population

Despite three decades of global focus on patient safety, ageing patients remain particularly vulnerable. Older people are more likely to experience adverse events not because of their disease and comorbidities, but because of the way these diseases are treated. Ageing patients have complicated health needs and require a mix of services delivered by numerous health professionals in different types of facilities. When care is poorly coordinated—for instance, when treatments for one condition negatively affect another, or when medication causes harmful side effects—it is not just inefficient; it means that care is unsafe and of poor quality. In many cases, no single provider takes ownership of a patient’s full care journey. On many occasions, patient records are not shared among health professionals leading to dangerous gaps and missed information.

Ageing patients can be marginalised in healthcare. Even in resource-rich countries, chronically ill and home-bound patients have limited access to health services with delayed or no clinical responses, posing a serious risk. Cognitive decline (dementia), emotional and behavioural disorders require sensitive and safe healthcare approaches. These patients often cannot advocate for themselves and rely entirely on families or overstretched systems. Standardised treatment protocols may overlook their unique needs, leading to unintentional harm.

Nursing homes: A Gap in Patient Safety

Growing numbers of older people find themselves in nursing homes, residential care facilities (St Clair et al. 2022) rehabilitation centres and long-term care hospitals—places intended to offer support for those who cannot be cared for at home. Evidence shows that the safety culture in many of these environments lags behind that of hospitals (Bakerjian 2024). Nursing homes and rehabilitation centres performed poorly across nearly all safety domains and scored lower than hospitals (Castle 2007; Halligan 2014; Allen 2016).

Geriatric Syndromes: Preventable Harm in Ageing Patients

Geriatric syndromes—delirium, falls, pressure ulcers and malnutrition/dehydration —represent common and serious patient safety concerns. These conditions often stem from mismanagement of treatment, are largely preventable and demand a systems-based approach to care (Inouye et al. 2008).

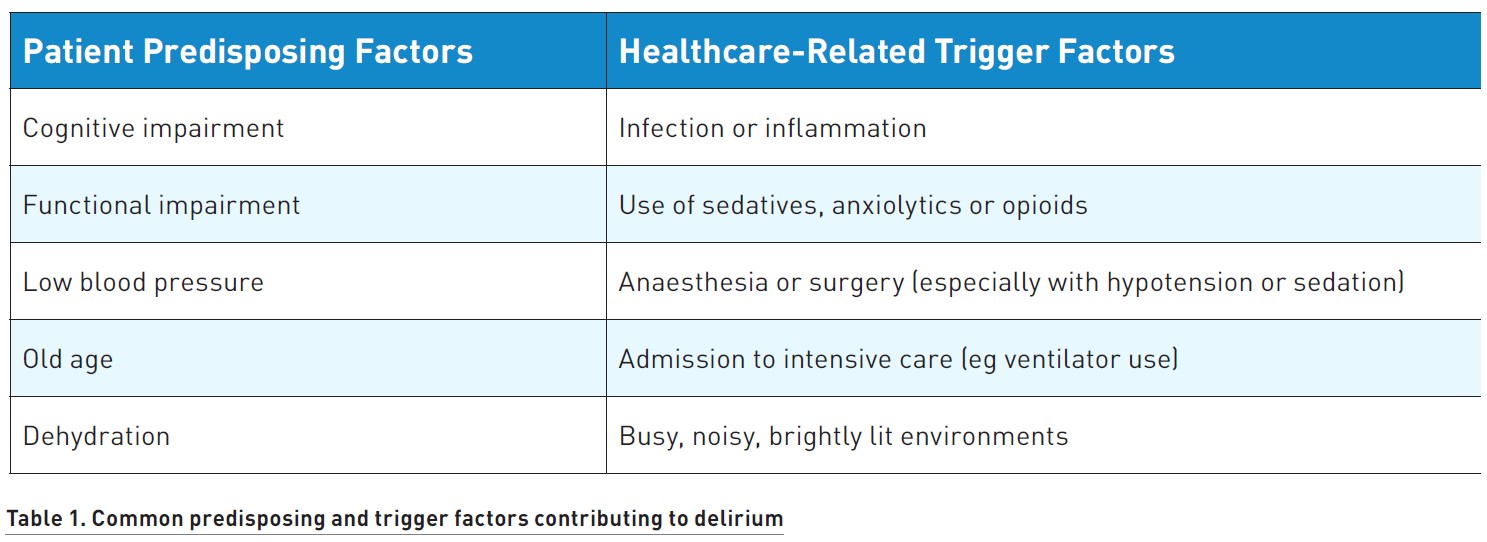

Delirium

A frequent and serious neuropsychiatric syndrome, characterised by a sudden disturbance in consciousness, attention and cognition. Up to 67% of cases go undiagnosed, are mistaken for dementia, psychosis or depression — largely due to a lack of screening and staff training (Wass et al. 2008). Delirium increases the risk of falls, dementia and accelerates towards death.

Prevalence: 30–50%; ICU up to 80%; post-surgery 15–70% (Martins et al. 2012).

Mortality: 25–33% in-hospital mortality (Al Farsi et al. 2023).

Length of hospital stay: 21 days vs. 9 days without delirium (Martins et al. 2012).

Preventing delirium in ageing patients requires a multifaceted approach:

- Implement routine screening for early recognition of patient risk.

- Regularly review medications, particularly anxiolytics and sedatives.

- Support patients’ physical health through proper nutrition and hydration.

- Address sleep deprivation.

- Enhance nursing care quality and provide targeted staff training.

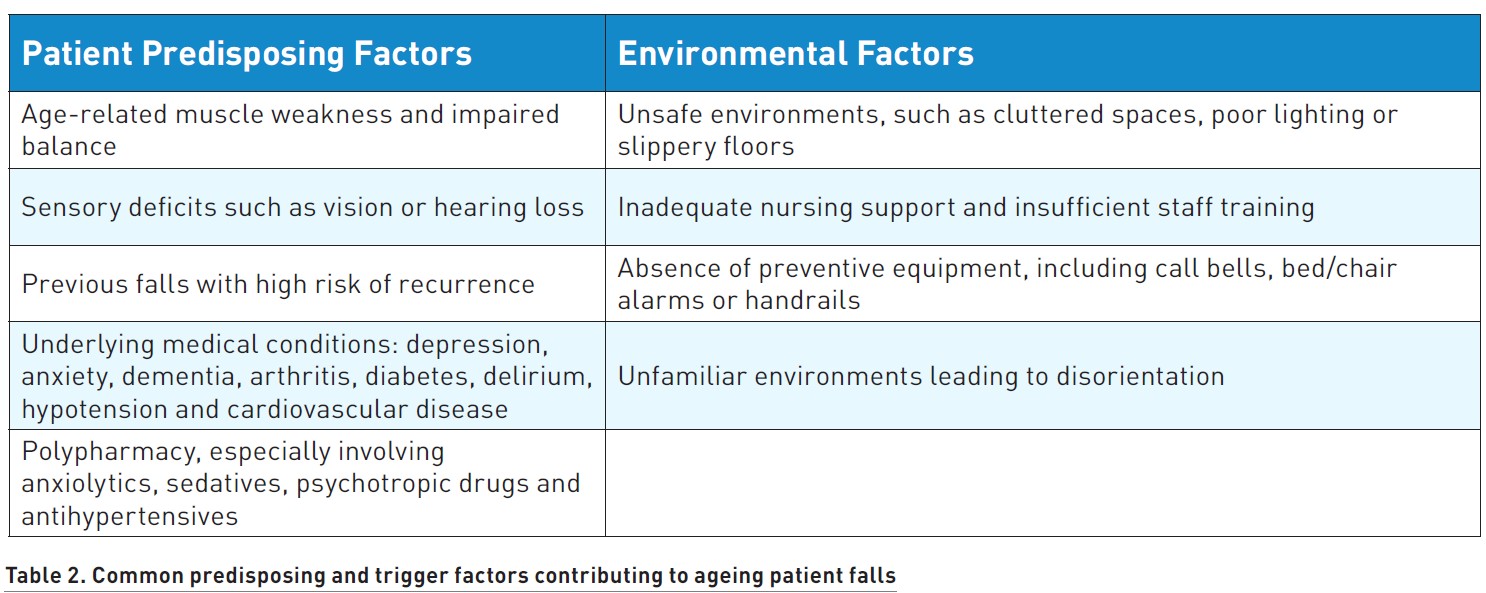

Falls

Another patient safety concern relates to falls among ageing patients. Falls are common and serious, occurring at high rates at home-bound and hospitalised patients.

Prevalence: 28% and 35% of people over 64, and 32% to 42% over 70, experience at least one fall each year (Xing et al. 2023).

Morbidity or mortality: 30% of falls lead to injury, with 4–6% of fractures, subdural hematomas or death (Krauss et al. 2005).

Length of hospital stay: 37.2 days of hospitalisation—compared to 25.7 days for controls (Locklear et al. 2024); according to one analysis in the UK, additional stay was 2.4 weeks per patient (Al Sumadi et al. 2023).

Preventing falls in ageing patients requires the following measures:

- Enhance the environment with safety modifications such as non-slip flooring, bed mat alarms and motion-sensitive lighting.

- Improved nursing care through hourly rounding and targeted staff training.

- Address patients’ sensory impairments by improving vision and hearing support.

- Conduct regular medication reviews, focusing on drugs that may cause dizziness, confusion, frequent urination or impaired balance.

- Educate patients and family members on fall risks and prevention strategies.

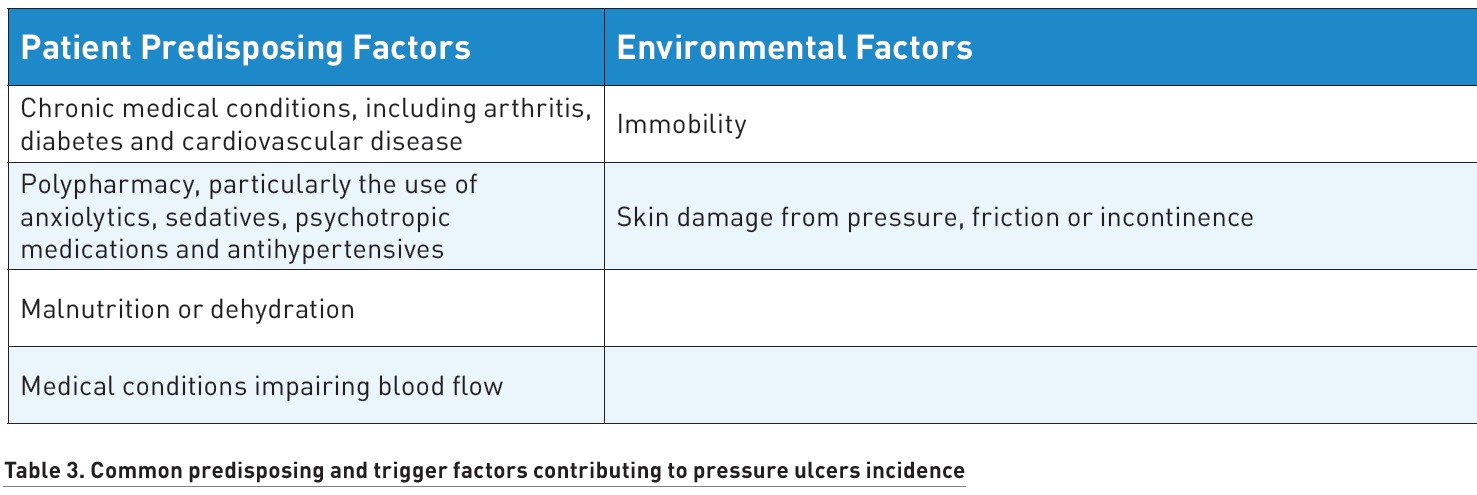

Pressure Ulcers

A third patient safety concern relates to pressure or decubitus ulcers, a significant concern for those who are immobile or in long-term care. Its high incidence indicates a diminished quality of care that can be considered unsafe.

Prevalence: 6.24% of patients over the age of 70 years compared to 3.41% in other age groups (NHS 2013). In nursing homes, the prevalence is around 11% (Lyder et al. 2008).

Morbidity or mortality: the risk of death doubles compared with those without ulcers (Song et al. 2019). 66% of those with pressure ulcers died within a 12-week follow-up (Khor et al. 2014).

Length of hospital stay: an average of 5–8 days to hospitalisation per ulcer (Labeau et al. 2020). 0.9 up to 14.1 days, depending on severity and setting (Triantafyllou et al. 2021).

Preventing pressure ulcers in ageing patients requires the following interventions:

- Conduct regular risk assessments using validated pressure ulcer assessment tools.

- Reposition patients at least every two hours to relieve pressure on vulnerable areas.

- Use pressure-redistributing surfaces, such as specialised mattresses, cushions or smart mattresses with sensors and alarms.

- Perform daily skin inspections, moisturise dry skin and manage incontinence.

- Ensure adequate nutrition and hydration with high-protein, high-calorie diets.

- Improve nursing care and provide ongoing staff education on pressure ulcer prevention.

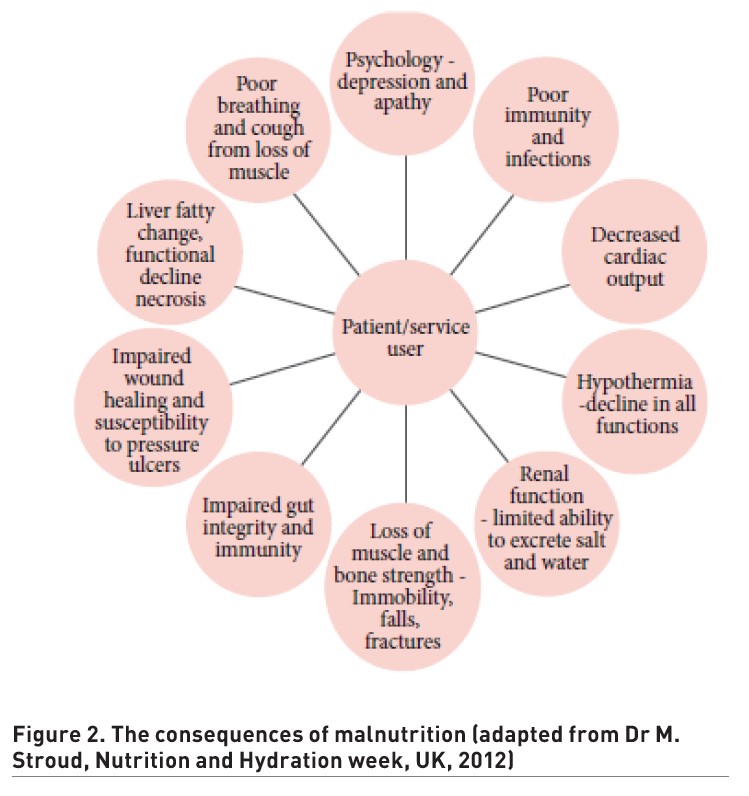

Malnutrition and Dehydration

Malnutrition and dehydration in ageing population is a widespread yet an under-recognised patient safety issue. Millions of older patients across diverse healthcare settings worldwide suffer from malnutrition and dehydration Both are associated with poor clinical outcomes, preventable contribution to illness and increased mortality.

Prevalence: A U.S. study found malnutrition affects 0–15% of ambulatory outpatients, 35–65% of hospitalised patients with acute illness and 25–60% of nursing home residents (Hajjar et al. 2003).

Morbidity or mortality: Malnutrition in hospitalised ageing patients is 2–3 times higher mortality compared to well-nourished peers (Norman et al. 2008). Loss of lean body mass leads to frailty, falls and fractures. Dehydration may lead to falls and orthostatic hypotension, urinary tract infections, impaired glucose control in diabetes, constipation and many other

Malnutrition and dehydration stem from a combination of individual risk factors and systemic failures in care delivery. Improving them requires the implementation of the following strategies:

- Screen patients regularly to identify those at risk of malnutrition or dehydration.

- Provide accessible food and fluids at all times in hospitals, clinics and nursing homes.

- Assist patients who require help with eating or drinking.

- Record all food and fluid intake accurately to monitor nutritional and fluid status.

More information is available in the landmark Francis Report (Francis 2013).

Medication Safety

Medication safety in older adults is a significant concern due to age-related physiological changes and the high prevalence of polypharmacy. As people age, they are more likely to use several medications simultaneously because of their multiple chronic conditions.

Ageing people process medicines less efficiently, making them more vulnerable to adverse drug events (ADEs). Compounding this risk is the tendency of healthcare providers to prescribe—and often overprescribe—medications for the multiple conditions that typically affect ageing patients. ADEs account for around 20% of emergency department visits among older people in the U.S., with nearly half being preventable (Pretorius et al. 2013; Shevni et al. 2019).

The hidden risks of polypharmacy in ageing patients include:

- Polypharmacy: Taking five or more medications simultaneously—a common scenario among older patients—is one of the most significant risk factors for ADEs.

- Age-related physiological changes: Decline in liver and kidney function affects how drugs are metabolised and cleared from the body.

- Cognitive impairment: Some medicines can trigger dementia. At the same time, dementia impacts the ability to manage medications safely and consistently.

- Frailty and mental decline: These factors can affect adherence and increase vulnerability to adverse effects.

Polypharmacy is a major factor contributing to medication-related harm. For instance, drugs used for one condition may negatively affect another. A medication prescribed for glaucoma might lower blood pressure too much, reducing brain oxygen supply and impairing cognitive function. In polypharmacy, adherence to treatment regimens can be challenging due to cognitive decline or physical limitations.

Medication errors can occur at any stage of the treatment process—prescribing, dispensing, administering or monitoring. Errors of commission, involve wrong action taken such as prescribing the wrong dose or choosing an inappropriate route of administration. Errors of omission, involve failure to act, such as failing to consider a medication’s impact on co-morbidities, its organ toxicity or potential drug-drug interactions. Both types of errors can lead to significant patient harm.

Even when medications are used correctly, some patients may experience side effects. The risk is particularly high in nursing homes, where residents may experience up to 10 ADEs per 100 resident–months, with 40% being preventable (Al-Jumaili et al. 2017).

Some medications carry heightened risks for ageing patients, particularly anticholinergics, psychiatric drugs and antibiotics. Anticholinergic agents—often used to treat incontinence or depression—can lead to confusion, memory loss and increased risk of dementia, especially with long-term use. Antipsychotics, sometimes prescribed for behavioural symptoms in dementia, are linked to serious complications including pneumonia, stroke and kidney injury, and should be reserved for short-term use when strictly necessary. Benzodiazepines, commonly used for anxiety or insomnia, significantly increase the risk of falls, memory impairment and dependence.

Most ADEs are caused by commonly used medications that have risks but offer significant benefits if used properly. These include:

- antidiabetic agents;

- oral anticoagulants;

- antiplatelet drugs;

- opioid pain medications.

Their potent physiological effects can complicate patient safety—for example, blood pressure medications may lower blood pressure too much, leading to dizziness and increasing fall risk.

Drug–drug interactions pose another serious concern. Warfarin, a commonly used anticoagulant, is especially prone to interactions with other drugs like antibiotics, and such interactions are a major cause of medication-related hospitalisations. If not used appropriately, these four medication classes are responsible for nearly 60% of emergency department visits for ADEs among patients over 65 (Shehab et al. 2016).

Patient Safety Issues in Medication Errors

Medication errors can result from both active failures and latent system flaws. Active errors, made by frontline clinicians, involve prescribing the wrong dose or medication and typically stem from cognitive issues: biases or knowledge gaps due to inadequate training. In some cases, clinicians may rely on outdated practices or fail to consider updated guidelines.

Latent errors, by contrast, arise from broader system weaknesses, including poor communication, time pressure, information overload, lack of standardised review processes and undue influence from pharmaceutical companies.

A persistent blame culture in healthcare further exacerbates the issue. When professionals fear punishment, they may avoid reporting near misses or ADEs, limiting opportunities for institutional learning and safety improvement.

Interventions to Reduce Medication-Related Harm

System-level interventions include regular pharmacist-led medication reviews, which are proven to reduce ADEs, and incorporating pharmacists into multidisciplinary care teams during hospital rounds to ensure that drug regimens are correct and optimised.

Person-centred care encourages shared decision-making and re-evaluation of medications in light of patient needs.

Education and training are also crucial. For healthcare professionals, understanding medication safety in ageing patients—such as recognising high-risk drug classes or common drug interactions—can significantly improve patient safety.

Technology-driven solutions, such as AI support tools, computerised physician order systems and bar-coded medication administration, enhance tracking, reduce transcription errors and promote safe administration of medicines.

Culture of safety is also critical. Encouraging the open reporting of errors and near misses, without fear of blame, enables health systems to detect patterns, identify systemic vulnerabilities and inform targeted interventions to improve medication safety.

Preventing patient harm from medication error requires a shift toward more individualised, appropriate prescribing and administration practices, as well as regular medication reviews. System-level changes—such as improved training, better reporting cultures and use of safety tools and technology—must complement person-centred care.

Healthcare-Associated Infections

Although not classified as a geriatric syndrome, healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) pose a significant risk to ageing patients due to weakened immune function, multiple comorbidities, malnutrition and reliance on invasive medical devices. Older adults account for approximately 55% of all HAI infections. Common HAIs in this population include catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), surgical site infections (SSI), central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and secondary bacteraemia.

Prevalence: A 2011 prevalence study (Cairns et al. 2011) reported HAI rates as follows:

- 11.5% in patients >85

- 11.27% in ages 75–84

- 10.64% in ages 65–74

- 7.37% in those <65

Reducing HAI burden in the ageing patient requires:

- Strict hand hygiene protocols;

- Effective antibiotic stewardship programmes;

- Standard precautions: gloves, masks, gowns, safe handling of sharps;

- Ongoing education and performance feedback for healthcare workers;

- Active surveillance and screening for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs);

- Targeted prevention strategies in high-risk patients (for example, catheter use) (WHO 2009).

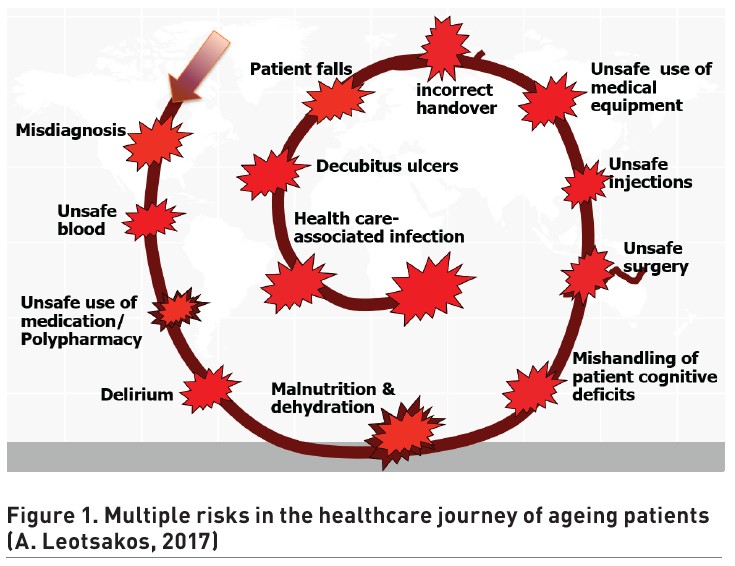

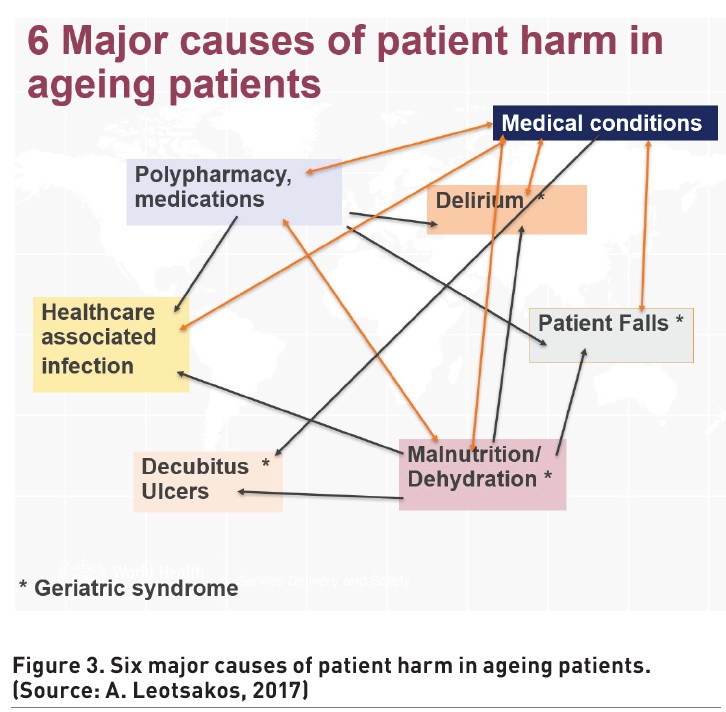

Interconnected Factors Contributing to Unsafe and Poor-Quality Care

The diagram illustrates the complex interconnections between medications, the four geriatric syndromes and HAI contributing to significant patient safety challenges in ageing patients. The overlapping arrows emphasise the interconnected nature of these health challenges.

Other common patient safety challenges in ageing populations include:

- Misdiagnosis or missed or delayed diagnosis

- Clinical decision making, for example, failure to act on test results, overuse or underuse of treatments, cognitive bias in clinical judgment.

- Mishandling of patient sensory, cognitive or functional impairments by healthcare professionals.

- All priority patient safety challenges affecting all ages, such as unsafe surgery, unsafe injections, unsafe blood products, injuries due to medical devices and others.

In addition, there are many structural factors contributing to unsafe care for the ageing populations including:

- communication failures such as poor coordination during patient handovers across different care settings;

- language and health literacy or understanding with patients;

- inadequate communication among healthcare professionals;

- organisational failures such as absence or weakness of safety culture in hospital and non-hospital facilities (nursing homes, rehabilitation centres and long-term care institutions);

- no regulation or accreditation;

- inadequate staffing or skill mix or untrained staff;

- fatigue and burnout of healthcare professionals;

- fragmented care coordination and others.

Conclusion

The global rise in ageing populations is creating unprecedented challenges for health systems. Ageing patients face a heightened risk of harm due to their complex health needs, care delivered across different settings, and environments not designed for their vulnerabilities. Geriatric syndromes, along with HAI, unsafe use of medication and other patient safety challenges, are major but preventable contributors to poor outcomes, extended hospital stays, morbidity and mortality. The current care landscape often lacks the safety culture, coordination, healthcare staff training and specialised attention ageing patients require. Meeting the needs of this growing population demands urgent investment in integrated, patient-centred and safety-focused care systems.

Conflict of Interest

None

References:

Al Farsi RS et al. (2023) Delirium in Medically Hospitalized Patients: Prevalence, Recognition and Risk Factors: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin, 7;12(12):3897.

Al Sumadi M et al. (2023) Inpatient Falls and Orthopaedic Injuries in Elderly Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis From a Falls Register. Cureus, 13(15):1–10.

Al-Jumaili AA & Doucette W (2017) Comprehensive Literature Review of Factors Influencing Medication Safety in Nursing Homes: Using a Systems Model. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(6):470–488.

Allen M (2016) Rehab hospitals may harm a third of patients, report finds. NPR, July 21 (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/07/21/486756178/rehab-hospitals-may-harm-a-third-of-patients-report-finds

Bakerjian D (2024) Long-term care and patient safety. AHRQ PSNet (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/39/Long-term-Care-and-Patient-Safety

Cairns S et al. (2011) The prevalence of health care–associated infection in older people in acute care hospitals. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 32(8):763–767.

Castle N (2007) Nursing home administrators' opinions of the resident safety culture in nursing homes. Health Care Manage Rev, 32(1):66–76.

Francis R (2013) Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Executive Summary. The Stationery Office (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-the-mid-staffordshire-nhs-foundation-trust-public-inquiry

Hajjar R et al. (2003) Malnutrition In Aging. The Internet Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology, 1(1) (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from ispub.com/IJGG/1/1/4920

Halligan M (2014) Understanding safety culture in long-term care: a case study. J Patient Saf, 10(4):192–201.

Inouye S et al. (2008) Geriatric Syndromes: Clinical, Research and Policy Implications of a Core Geriatric Concept. J Am Geriatr Soc, 55(5):780–791.

Khor HM et al. (2014) Determinants of mortality among older adults with pressure ulcers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr., 59(3):536–41.

Krauss M et al. (2005) A Case-control Study of Patient, Medication, and Care-related Risk Factors for Inpatient Falls. J Gen Intern Med., 20(2):116–122.

Labeau SO et al. (2020) Prevalence, associated factors and outcomes of pressure injuries in adult intensive care unit patients: the DecubICUs study. Intensive Care Med, 47(2):160–169.

Locklear T et al. (2024) Inpatient Falls: Epidemiology, Risk Assessment, and Prevention Measures: A Narrative Review. HCA Healthc J Med., 1;5(5):517–525.

Lyder CH et al. (2008) Pressure ulcers: A patient safety issue. In: Hughes RG (Ed.), Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2650/

Martins S & Fernandes L (2012) Delirium in elderly people: a review. Front. Neurol., 3:1–12.

NHS Safety Thermometer (2013) NHS Safety Thermometer Report: England 2013. NHS Digital (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-safety-thermometer

Norman K et al. (2008) Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr., 27(1):5–15.

Pretorius R et al. (2013) Reducing the Risk of Adverse Drug Events in Older Adults. Am Fam Physician, 87(5):331–336.

Shehab N et al. (2016) US Emergency Department Visits for Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013-2014. JAMA 316;(20):2115–2125.

Shevni C et al. (2019) Managing the Elderly Emergency Department Patient. Geriatrics/expert clinical management, 73(3):302–307.

Song Y-P et al. (2019) The relationship between pressure injury complication and mortality risk of older patients in follow‐up: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int Wound J, 13;16(6):1533–1544.

St Clair B et al. (2022) Incidence of adverse incidents in residential aged care. Aust Health Rev 46(4):405–413.

The Lancet Healthy Longevity (2021) Care for ageing populations globally. Lancet Healthy Longev., 2(4):e180.

Triantafyllou C et al. (2021) Prevalence, incidence, length of stay and cost of healthcare-acquired pressure ulcers in pediatric populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 115:103843.

Wass S et al. (2008) Delirium in the elderly: a review. Oman Medical Journal, 23(3):150–157.

Wimo A et al. (2013) The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 9:1–11.

World Health Organisation (2009) WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906

World Health Organisation (2012) Good Health Adds Life to Years: Global Brief for World Health Day 2012 (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-DCO-WHD-2012.2

World Health Organisation (2021) Global Health Estimates: Life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates

World Health Organisation (2025) Ageing (accessed: 04 July 2025). Available from who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1

Xing L et al (2023) Falls caused by balance disorders in the elderly with multiple systems involved: Pathogenic mechanisms and treatment strategies. Front Neurol, 23;14:1–8.