What is the potential for a more rounded healthcare approach?

If we want to implement the WHO definition of health, we need to build people-centred care and service systems that we will evaluate the patient as a whole.

In 1948, the World Health Organization defined the concept of health as follows: “A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO 2018). This definition suggests we evaluate the patient from a very broad perspective. However even today, it is still difficult to say we do so especially for the follow-up of chronic and complex illnesses.

Since people may not have a complete perception of their own health condition due to health literacy, as the healthcare sector and professionals, we have to think of the patient as a whole in order to provide him/her with an integrated quality healthcare. According to my observations, doctors adopt the same approach to all diseases in the direction of their own medical knowledge and experience. This approach may not meet the patient’s individual needs and values. I even know doctors who don’t take enough time to listen to the patient and don't look at his/her face. This is a kind of operational blindness.

Isn’t it still a valid definition after 70 years?

From those years until today, could we evaluate and treat the patient as a whole?

Dr. Samuel Silver (2008) writes these words about a cancer patient in his report 'Cancer care for the whole patient - a new Institute of Medicine report:

“In the rush of busy clinics, during our previous visits, I really had not paid attention to my patient's affect. If I did think about it, I would probably have passed it off to a minor, totally understandable “reactive” depression. I was not “Meeting the Psychosocial Health Needs” (the subtitle of the report) of my patient.”

According to a recent survey by Quest Diagnostics, 95% of primary care physicians (PCPs) say they became a doctor to treat the “whole patient.” Yet, 66% of PCPs say they don’t have enough time and/or bandwidth to worry about non-physical, social issues of their older patients with multiple conditions. The survey also demonstrates two out of five patients (44%) want to tell their doctor about their medical conditions, but not about non-medical issues they face such as loneliness, financial, and difficulties of transportation. Many of them are afraid of falling in or outside the home and of developing other conditions, but they do not share these concerns with others for fear of being a “burden” (Dlott 2018).

Integrative medicine seeks to embrace a more comprehensive view of healing and to see and care for individuals in their completeness. More and more research demonstrates that integrative care results in improved health outcomes. Contrary to expectations, today’s medical specialisations seem to focus on individual organs rather than systems. In addition, unless the patient is aware of his/her chronic condition and gets support to deal with it, it’s impossible to assess his/her health status holistically. For example, a cardiac patient with a sedentary life, inappropriate nutrition regimen, lack of health literacy and an unhappy professional life, cannot be fully evaluated. It is obvious that the healthcare model will continue to be reactive, rather than proactive, if health system isn’t designed to holistically understand and support patients.

A person who enters the healthcare system at any stage because of health needs do not easily achieve optimal benefits when the data received by health services from various departments hasn’t been integrated and evaluated by certain individuals. In this context, a holistic view of patients is significant. Basically, people do not have a perception of their own health conditions. Health is personal so that each patient should be evaluated with the environment they live in and work as well as the people who they interact with. In other words, we need to evaluate people within their own habitat as an individual and build health systems that will ensure that we get the right data to help us evaluating the patients holistically. Otherwise, there will be a communication gap between patient and healthcare provider, which will lead to poor clinical outcomes and negative patient experience.

The providers should meet patients where they are functionally, emotionally, and socially in order to establish a quality health services centred on a patient. Additionally, in order to understand the perception of health of the patient, providers should consider mental state, family life, and beliefs of patient.

Having created a holistic patient evaluation system, Iora Health Center writes on its website:

“We are restoring humanity to healthcare. We believe in primary care that puts people first. Because when we can connect on an individual level, we can impact the entire healthcare landscape” (Dudgeon 2015).

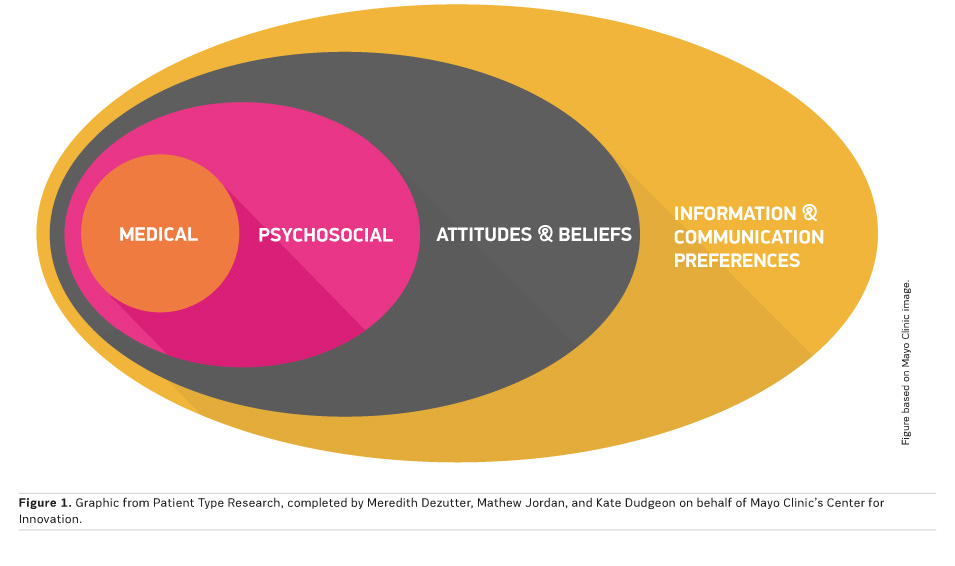

According to Mayo Clinic's Center for Innovation, holistic understanding of a patient comprises many layers (Figure 1).

At the core of every patient is “Medical” condition. According to this model, an individual who has a number of health issues perceives his/her medical needs as an interconnected whole. No matter whether it is a minor or major, medical or health-related need is what defines the care request and clinical interaction (Dudgeon 2015). The patient may have several healthcare problems and be aware of them, but the specialised clinician probably focuses on a single condition. Consequently, the condition cannot be evaluated as whole.

The second is “Psychosocial” layer denoting a patient’s mental and emotional state, social system, and functional capabilities, deeply affected by beliefs or perceptions he/she has formed over time regarding one’s health and care. This layer is crucial to understand because it can inhibit or enable a person’s ability to actively take part in caring for himself/herself. For example, many people find themselves in a deep depression upon a diagnosis, after having realising that their once-normal state no longer exists.

Another component of the whole patient is one’s “Attitudes and Beliefs”, which break into two parts. Beliefs often depend on the individual’s own experiences or those of his/her family and friends. People often share with others an overly positive or negative experience of receiving care. Second attitudinal category depends largely on how much involved the individual is in his or her own health and care (Dudgeon 2015).

According to this model, the last layer that makes up a whole patient is “Information and Communication” preferences: how someone learns, when someone is open to learning, how someone seeks out information, and how someone prefers to exchange information with a care team. Nowadays, I see and know that most patients communicate with the physicians via email, Whatsapp or any other digital way. They send messages to their doctor about their health problem rather than initially scheduling an appointment.

Another study, the Institute of Medicine’s report Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs makes a series of recommendations to improve cancer care. This article focuses on the recommendations for the oncologists. The report suggests that failure to address psychosocial issues “compromises the effectiveness of health care and thereby adversely affect the health of cancer patients.” The IOM therefore proposes a new standard of care for integrating psychosocial care into routine care to overcome these barriers and improve care for the whole patient.

We all know the saying, “Treat the patient, not just the disease.” Every disease can have a different course in every person. Diagnosis and treatment approaches may differ according to patient as individually. So, we have to build people-centred care and service systems that we will evaluate the patient as a whole. Models such as this one can be used as a tool to start. It is obvious that the physicians have the critical role within this system. And we know that the physicians want the best healthcare outcomes for their patients. So, what are we waiting for?