HealthManagement, Volume 17 - Issue 5, 2017

Why it should and how it can be done

How one healthcare body is introducing education on sustainable healthcare across the sector.

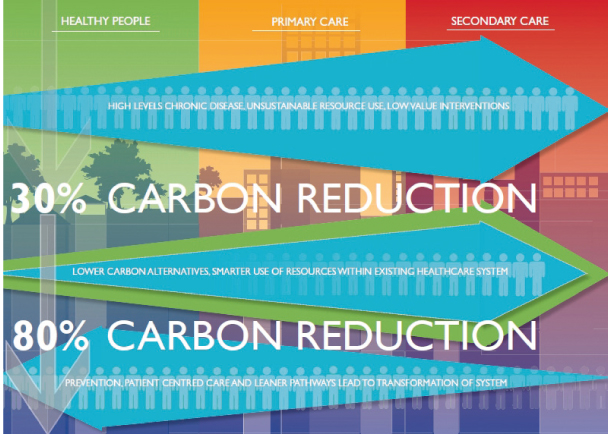

Environmental change is an increasingly important determinant of health and of the ability of societies and healthcare services to respond to ill health. Climate change has been recognised as the “biggest global health threat of the 21st Century” (Costello et al. 2009). Its effects on health are predicted to be overwhelmingly negative, impacting on the social and environmental determinants of health (World Health Organization, 2017). Healthcare professionals have a duty to protect health and can do this by focusing on the four principles of sustainable clinical care: prevention, patient empowerment and self care, lean systems and low carbon alternatives.

Furthermore, there is an imperative and a legal duty to reduce waste and resource use, in particular carbon emissions. The NHS is committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 80% on 1990 levels by 2050 (UK Parliament, 2008). In addition to this, environmental, social and financial resource constraints risk impacting on the quality of healthcare services. Recognising this, the Royal College of Physicians has identified sustainability as a domain of quality (Royal College of Physicians, 2011). Doctors need to be equipped to lead the delivery of a sustainable health service.

It is imperative that future doctors are capable of meeting these challenges and medical education is central to a sustainable future for healthcare. Current areas of focus such as public health and health inequalities, quality improvement, medical leadership and ethics can usefully be approached through the lens of sustainability.

Embedding sustainability into clinical care.

Embedding environmental sustainability into the health sector has been the goal of the Centre of Sustainable Healthcare (CSH ) since 2008, when it was established. NHS estates were originally the main focus of efforts to improve sustainability however this approach was reassessed when research on the carbon footprint of the NHS found that clinical services were responsible for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions (Sustainable Development Unit, 2008).

As a means to address this CSH developed a particular focus on engaging clinicians and promoting the concept of sustainable clinical practice. It has done this by setting up a sustainable specialties programme, developing a Sustainable Quality Improvement methodology and working with hospital Trusts on sustainability projects.

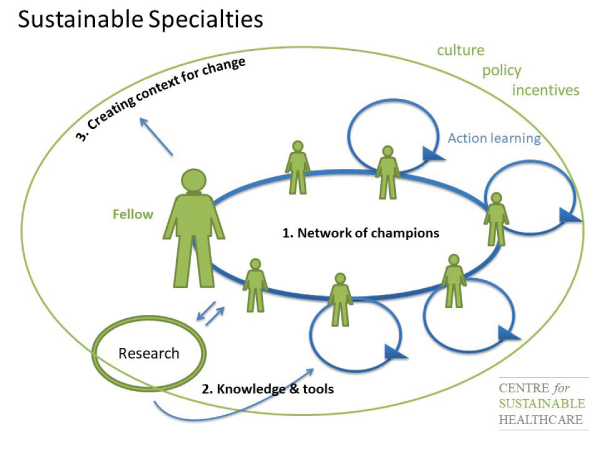

The Sustainable Specialties programme fosters change within clinical communities. It does this by supporting clinicians to learn about sustainability, promote and teach about it, evaluate their specialty and determine where sustainable changes can be made (in postgraduate colleges, at a commissioning and policy level or on the ground with colleagues and patients) and get involved in innovating themselves. This approach was originally and successfully demonstrated in kidney care in 2009-11 when CSH established a Green Nephrology Fellowship. The fellows developed a Network of local sustainability representatives in more than 80% of UK kidney units. They also worked on a programme of research, annual awards and practical initiatives developed within renal medicine. Following this, in 2013, The Royal College of Psychiatrists became the first medical Royal College to fund a Sustainable Specialty Research Fellowship. The fellow was responsible for organising a Sustainability in Psychiatry Summit and the launch of an RCPsych Sustainability Award. Focussing on policy and commissioning he produced a report for the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (Maughan and Ansell, 2014) and a guide to sustainable commissioning (Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health & Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, 2015).

As this approach has evidenced, enabling clinicians to make change from within their own specialties has the potential to have a significant impact on clinical care. CSH has therefore developed scholarship programmes within other specialties. CSH training on sustainability, mentoring, resources (including carbon footprinting), advisory groups and networks have all helped support the fellows and scholars in their efforts and have been a fundamental part of embedding sustainability into clinical practice. Specialty networks have been an invaluable tool in promoting sustainability and transformative models of care but also to provide support to those endeavouring to make sustainable change. They help avoid duplication of work and bring a wealth of knowledge and advice to all those engaged in sustainability networks.sustainablehealthcare.org.uk.

Other tools also help provide clinicians with a framework to make sustainable change. One of these tools is a Sustainable Quality Improvement (SusQI) methodology. Increasingly clinicians are being expected to get involved with quality improvement projects. Understanding how to study, plan and execute changes to healthcare pathways that involve not only improvements in health outcomes and reductions in financial costs (as in traditional quality improvement) but also reduce environmental and social costs as well can be difficult. The SusQI method provides a clear way to do this and has been used effectively by clinicians to develop and subsequently evaluate work to improve the quality of healthcare.

Along with its project and research work with CCG’s, industry and other bodies (e.g. carbon foot printing a service, comparing the sustainability of different care pathways, supporting the expansion of inhaler recycling) CSH also works with hospital Trusts to run the Green Ward Competition. This is a clinical engagement programme where clinical teams are recruited to compete against one another and are supported by CSH to develop sustainability projects and measure environmental, financial and patient/staff benefits. This alternative method of working with clinicians in a clinical setting has proved popular and successful leading to cost and carbon savings as well as patient benefits (Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, 2017).

Embedding sustainability in clinical care is not just about making change inside the clinic setting but also outside. Acknowledging that green spaces are part of the tapestry of promoting and sustaining health, CSH ’s NHS Forest project has worked with healthcare organisations to value their green spaces and promote better use of the natural environment by staff, patients and local communities.

Through these mechanisms above it has been possible to raise the profile of sustainability within clinical medicine and to make sustainable change. Using this approach has ensured that changes have been driven by those who know the system best and have not been imposed from above.

Embedding sustainability into medical education

Sustainability is gradually being embedded into medical education. CSH has facilitated this by hosting the Sustainable Healthcare Education (SHE ) Network. This is a network of students and educators interested in preparing health professionals to build and work in a sustainable health service. The network has been instrumental in driving sustainable change within medical education. In September 2011 the General Medical Council asked the SHE Network to make recommendations for priority learning outcomes for sustainability, to inform the on-going development of undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula. The resulting priority learning outcomes have been referenced in the GMC’s outcomes for graduates' (General Medical Council, 2015).

Since then the SHE network has continued to work in medical education nationally and internationally researching, teaching and promoting sustainability. Members of the SHE Network have worked with UK medical schools to develop courses on sustainability (Walpole and Mortimer, 2017) and a bank of case studies and teaching materials is being collated.

The SHE Network aims not only to support effective teaching, learning and assessment for sustainable healthcare literacy but also to effect change in curricula and work further with regulatory bodies to bring sustainable healthcare into mainstream teaching. Embedding sustainability into clinical care and medical education requires a multifaceted approach that utilises the ability, knowledge and networks of those working in healthcare and healthcare education, supported by a framework of resources, methodology and research. Regulatory bodies, guideline, research, standards and reference organisations as well as providers, commissioners, industry and other health groups have all been engaged in the approach that CSH has taken, focussing on the power of individuals and networks to drive improvement and a more sustainable way of working.

Key Points

- There are important legal, ethical and public health reasons

to embed sustainability into clinical care and medical education

- Clinicians can effectively drive sustainable change from

within their specialty

- Networks are essential to support and promote sustainability

- Sustainable healthcare education is fundamental to a

sustainable future

References:

Centre for Sustainable Healthcare. (2017) Green Ward Competition. [Accessed 4 Sept 2017] Available from http://sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/what-wedo/green-ward-competition [Accessed 4 Sep. 2017].

Costello, A., Abbas, M, Allen, A, Ball, S, Bell, S, Bellamy, R., Friel, S, Groce, N., Johnson, A, Kett, M and Lee, M (2009). Managing the health effects of climate change. The Lancet, 373(9676), pp.1693-1733.

General Medical Council, (2015) Outcomes For Graduates (Tomorrow’s Doctors). London: GMC. Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health & Centre for Sustainable Healthcare (2015) Guidance for Commissioners of Financially, Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Mental Health Services London: Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health.

Maughan, D. and Ansell, J. (2014) Protecting Resources, Promoting Value: a doctor's guide to cutting waste in clinical care London: Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.

Royal College of Physicians. (2011) A Strategy for quality: 2011 and beyond. London: Royal College of Physicians.

Sustainable Development Unit. (2008) NHS England Carbon Emissions Carbon Footprinting Report. Cambridge: Sustainable Development Unit.

UK Parliament. (2008) Climate Change Act. London: UK Government.

Walpole, S. and Mortimer, F. (2017) Evaluation of a collaborative project to develop sustainable healthcare education in eight UK medical schools. Public Health, 150, pp.134-148.

World Health Organization. (2017) Climate change and health. [Accessed 9 Sept 2017] Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs266/en/