HealthManagement, Volume 5 / Issue 3-4 / 2010

Author:

Tosh Sheshabalaya

HIT

Radical

healthcare reforms in the Netherlands in January 2006 saw the State replaced as

the central player in day-to-day operation of the healthcare system by private

health suppliers. Alongside, the difference between public and private health

insurance was abolished, and all adult residents were obliged to purchase basic

health insurance from a private firm.

The basic

package – based on an officially set premium – covers medical and dental care,

hospitalisation, and a variety of medical appliances, pharmaceuticals and

paramedical care. Complementing insurance can be purchased by individuals to

cover requirements beyond the basic package; insurance companies are, however,

free to set prices, and, unlike the basic package, can reject applicants.

In

spite of some early complaints that reforms would change the character of the

healthcare system in the Netherlands beyond recognition, the Dutch are

positive. The percentage of people who believe that the country’s health care system

functioned well has fallen only slightly – from 45 percent before reforms to 42

percent according to the government’s latest survey.

Structure of the System: Changing Roles

and Responsibilities.

The sweeping reforms of 2006 engendered a fundamental shift in the structure of the Dutch healthcare system. Nevertheless, in spite of the new dominance of the private sector and the transfer of responsibility to private insurance firms, healthcare providers and patients, the government retains a strong residual role in ensuring universal accessibility and affordability as well as ensuring the quality of healthcare.

A variety of new statutory and semi-official watchdog agencies have since been set up or their powers strengthened. They aim at avoiding the undesirable effects of over-reliance on market forces. Backing this is a legacy of self-regulation which characterised the Dutch healthcare system since the Second World War. Professional associations are responsible for re-registration schemes and are involved in quality improvement, for instance by developing professional guidelines.

Furthermore, in long-term care as well, increased competition among providers of outpatient services is changing the system considerably. The delegation of responsibility for domestic home care services to the municipalities has resulted in more diverse care arrangements.

In the aftermath of reforms, the Dutch health insurance system consists of three distinct components.

- A compulsory SHI (social health insurance) system, regulated by the Health Insurance Act (Zorgverzekeringswet) and covering the entire population for ‘basic’ healthcare. This is defined as essential curative care on the basis of demonstrable efficacy and cost-effectiveness, alongside an allowance to (partly) compensate lower incomes during their treatment. All Dutch residents contribute in two ways: a flatrate nominal premium, paid directly to the health insurer of their choice; an income-dependent employer contribution deducted from their pay and transferred to the Health Insurance Fund which allocates resources among the insurers according to a risk-adjustment system.

- A second compulsory social health insurance (SHI) scheme for long-term care, and covering those with chronic conditions. This is regulated by the Exceptional Medical Expenses Act (Algemene Wet Bijzondere Ziektekosten, AWBZ), and principally financed through income-dependent contributions. Payouts are regulated by (a rather complex) cost-sharing system and follows a formal medical assessment. Care is provided by dedicated care offices (Zorgkantoren), which are closely allied to health insurers.

- Complementary voluntary health insurance (VHI), which covers services excluded under the two above components.

Preventive healthcare and social support are financed through general taxation. According to the WMO Social Support Act, certain forms of home care are the responsibility of municipalities. These directly purchase the home care services from providers.

Certain municipalities have, however, developed their own regulations on eligibility and needs assessment, in some cases by outsourcing the process to the Centre for Needs Assessment (CIZ).

Primary Healthcare

In the Netherlands, general practitioners (GPs) function as gatekeepers for patient referral to specialists. All patients are listed with a GP. GPs thus play the key role in primary care in the country, a relatively rare situation compared to other continental EU countries – but with parallels to the UK.

Patients are free to choose and register with a GP and can also switch to another freely. GPs, however, retain the right to refuse a patient, principally if their rosters are too full, or should a patient live too far from their practice. This is crucial since patients access care outof- hours (at the night and weekends) through so-called GP

Posts (cooperatives of practitioners). The latter, in turn, also have a gatekeeping function for emergency care. Indeed, in certain cases, emergency care can be provided by GPs without referral to a hospital.

Nevertheless, the GP gatekeeper system is unhampered by logistics – given the demographic density of the Netherlands. According to a 2009 study by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, nearly 100 percent of the Dutch population can reach a GP within 15 minutes from their home. The central role of GPs dates back to efforts by the Dutch government in the 1980s to reduce fragmentation in the delivery of primary healthcare, which traditionally involved not only GPs but also pharmacists, psychologists, physiotherapists, nurses and midwifes.

However, after the 2006 reforms, the government has sought to reverse course and dilute over-dependency on GPs. Although the GP remains the key figure in the fabric of primary care, several tasks have been shifted towards other providers, most crucially specialised nurses. Since 2007, the latter have been allowed to prescribe medication – although diagnosis has to still be made by a physician. Overall, practice nurses have begun to play a major new role in general practice. Practice nurses take care of several categories of chronically ill, (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular diseases, as well as diabetes.

Meanwhile, physiotherapists and other categories of remedial after-care providers have also became directly accessible to patients, while occupational doctors have acquired eligibility to refer patients to secondary care.

In the Netherlands, patients contact their GP five times per year on average – well below the World Health Organisation’s Europe average of 7.9 and the EU- 12 average of 7.7 in 2007. During the same year, 41 percent of the population had an average of 1.8 contacts with a medical specialist. Just over 10 percent were admitted to hospital.

Source: European Central Bank, OECD, WHO, EU Commission, National Telecommunications Union (for Internet Statistics).

Hospitals in the Netherlands

The Netherlands has 93 healthcare organisations, covering a total of 141 hospitals and 52 outpatient clinics.

Hospitals provide secondary care, almost always after referral from GPs – as well as 24- hour emergency wards, to which access is obtained by both referrals and via public services such as the police and ambulance services.

Care is provided at both in-patient and outpatient departments (which also provide pre-hospitalisation diagnosis as well as posthospitalisation follow-up).

Apart from general hospitals, these include the following:

- 8 university hospitals

- 98 so-called categorical hospitals (for treatment of conditions such as renal failure, asthma, epilepsy) 120 independent treatment centres or ZBCs (providing elective, nonacute surgery via one-day admissions for conditions such as varicose veins, cataracts etc.)

- 50+ specialist referral centres (specialized in areas such as organ transplantation, IVF, cancer, and linked to university hospitals)

- 10 trauma centres, most of which are again linked to a university hospital or a group of university hospitals.

Most Dutch hospitals are non-profit institutions. Since 2008, however, the Dutch government has authorised a certain number of pilot projects which pay part of profits to shareholders. The scheme, which remains a topic of contentious debate, is part of the follow-up to the 2006 reforms, and seen as a means to generate investment for quality improvement and innovation. Since 2006, the government has abolished central planning of healthcare facilities; each institution has been given the mandate to develop its own capacity planning strategy.

Meanwhile, legislation to counterbalance ‘over-marketization’ of the hospital – in terms of a new corporate structure called a ‘social enterprise’ – is under discussion. Under such a structure, strategic decisions on quality and continuity of care will continue to be reserved for the hospital’s professional management and supervisory board.

Such concerns may not be wholly out of place. The quasi-marketisation of the Dutch healthcare system has resulted in the beginning of some vertical integration between different players. Although the legality of such moves remains disputed and their scale small, some health insurers have begun to open pharmacies and healthcare centres (one has made a bid, in a consortium, for taking over a hospital).

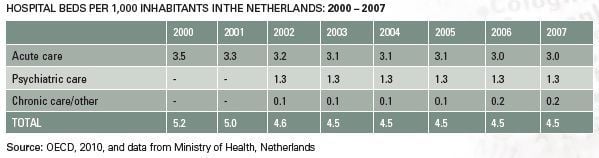

Bed Numbers

In 2007, licensed hospital bed availability in the Netherlands was 4.5 per 1,000 inhabitants. Of this, 3 beds (67 percent) were in acute care – a ratio which has remained steady since the year 2000. Psychiatric care accounted for the bulk of the remainder, with 1.3 beds per 1,000 inhabitants (a share of 29 percent of total beds).

In terms of numbers, the average hospital in the Netherlands has about 560 beds. The total number of beds in general acute care hospitals amounted to just under 45,000 and in academic hospitals about 6,600.

The variation per hospital was significant, between 135 and 1,350, while the larger academic hospitals showed far higher consistency In the same year, the size of general acute care hospital organisations varied between 138 and 1368 beds per hospital. The variation in availability in academic hospitals was much smaller: between 713 and 1307 beds.

Compared to other European countries, the number of hospital beds in the Netherlands is below the EU average. The rate of 4.5 per 1,000 compares to seven to eight in neighbouring Belgium and the Netherlands or France, and is closer (but slightly ahead of the 3.5 in Denmark, Norway and the United Kingdom).

Nevertheless, as in most European Union countries, the number of

hospital beds in the Netherlands has been steadily dropping, by over 15 percent

since the year 2000 – from 5.2 per 1,000 to its present 4.5. In terms of acute

care bed capacity, the number has also been steadily dropping – although, as

noted above, their share in total hospital bed capacity has been roughly the

same.

These trends are driven by a combination of similar factors as elsewhere in the European Union.

Firstly, spiralling healthcare costs have drawn attention to one of its largest components – length of stay, and there has been a rapid rise in the efficiency of use of bed capacity. Adding force to such a trend is the increase in availability of minimally invasive surgical techniques, which not only reduce length of stay in several interventions – but also permit one-day stays (a key factor underlining the presence of the 120 ZBC independent treatment centers). In 2009, Statistics Netherlands reported that approximately 46 percent of all hospital admissions were one-day admissions.

Secondly, treatment of chronically ill patients is increasingly being delivered in a patient’s home – and this is helped by enhancing the responsibility and mandate of specialist nurses (as discussed previously). In 2003, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport announced its goal of reducing the number of acute care beds per 1,000 inhabitants to approximately 2 in 2015. Nevertheless, after the 2006 reforms and the subsequent elimination two years later in central planning for hospitals, it is the latter themselves which are seeking such a goal.

Trends in Hospital Stay

The length of hospital stay in the Netherlands has traditionally been above the EU average (with the notable exception of Germany). In 2000, the average was nine days, as compared to five in Sweden, 5.6 in France, 7 in Italy, 7.7 in Belgium, 8.2 in the UK – and way above Denmark’s record of 3.8 days.

Such a state of affairs was due to several reasons. A near-scandalous level of waiting lists meant that patients needing continued care in a long-term care institution were forced to stay longer in acute hospitals. In addition, the Netherlands was late in seizing the possibilities of transferring patients from hospital to a home care setting – the subject of an in-depth study by the Board for Health Care Institutions in 2003.

Currently, the average length of hospital stay has fallen – especially sharply over the past five years – to an estimated six days (from nine in 2000). This compares well with fellow-straggler Germany’s performance (from 9.2 days in 2008 to 7.8 days in 2007).

As discussed, a key role in such a reversal has been played by the growth in oneday minimally invasive surgical interventions as well as home care.

Healthcare Financing

In spite of the ambitious reforms of 2006, overall health spending continues to rise in the Netherlands, growing marginally in 2007 to 9.8% GDP from 9.7% the year below. Although this is below the 10% peak in 2004, the share of health spending in GDP – as compared to just 8% in 2000 – has shown no sign so far of a trend reversal. This is due to underlying structural factors, not least an ageing population.

In constant PPP dollar terms, too, the rise in health spending is inexorable. On a per capita basis, between 2000 and 2007, this increased by 65% from just 2,337 USD to 3,837 USD.

Hospital Financing

Since 2005, Dutch hospitals are remunerated through a DRG-modelled system known as Diagnosis Treatment Combinations (DBCs). This involves price and quality negotiations between hospitals and insurers during the contracting process.

Free negotiations on price, however, remain confined to just over one-third of contracts, although their share has risen sharply from 20 percent in 2008 and 10 percent in 2005. In addition, capital investments have not been freely negotiable within the DBCs. Instead, the Dutch Health Care Authority (NZa) established a normative compensation. From 2009, capital investments have become part of the negotiation process between hospitals and insurers, but given the impact of the 2006 reforms, the situation remains in a state of flux.

In general, there are no third-party payers for home care. However, some municipalities outsource the settlement of income-dependent cost-sharing requirements to the Central Administration Office (CAK).

Physician Payment

Since the introduction of the 2006 reforms, payment of GPs has undergone a corresponding shift. GPs are now paid in the Netherlands via a combination of capitation fees and fee-for-service.

Private Spending

Out-of-pocket payments have been declining steadily in the Netherlands – from a share of 9 percent of total healthcare spending to 7.1 percent in 2005 and then sharply to 5.5 percent in 2007.

In constant PPP dollar terms, the sum has been stable. It was 213 dollars in 2007, compared to 210 dollars in the year 2000, but down from a peak of 246 dollars in 2005.

Co-payments range from a fixed amount for certain NHS services to a fixed proportion of the cost of a medicine.

Healthcare Staffing

Physician density in the Netherlands has risen steadily in recent years, from 3.2 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2000 to 3.9 in 2007. This is more or less in line with the EU average.

In 2008, there were over 8,800 practising GPs in the country, with an average 2,300 patients each. Just over half of all GPs (51 percent) work in group practices (3-7 GPs), 29 percent work in two-person practices and 20 percent work as sole practitioners. Most GPs are independent entrepreneurs or work in a partnership; some are also employed by another GP.

Latest available data on registered medical specialists date back to 2005, when there were a total of 16,500. The largest categories were psychiatrists (2,500), followed by interns (1,800) and anaesthesiologists (1,250). Within hospitals, approximately 75 percent of medical specialists are organised in (mainly independent) partnerships.

On the other hand, university hospitals in particular, have specialists directly employed, and on their payrolls.

In spite of efforts to emphasise the roles and responsibilities of nurses, their numbers have been declining – from over ten per 1,000 in 2000, to 8.7 in 2007. Although this reflects a reasonably satisfactory ratio of 2.2 per physician, nurse numbers will have to be boosted in the Netherlands, according to healthcare experts – in order to reduce physician and hospital workloads further, and contain costs. By comparison, nurse density per 1,000 inhabitants in 2007 in Germany was 9.9, in the UK ten, in Sweden 10.8 and in Belgium above 14.

Outlook and Prognosis

The 2006 package of health insurance reforms are seen as the first (albeit giant) step in an ambitious policy agenda on overhauling the Dutch healthcare delivery system. This highlights quality of care as a steering instrument and the promotion of cohesion in the entire care delivery chain (primary care, hospital care, at-home care and ambulatory care).

Towards this, the government aims to continue introducing incremental followon reforms to encourage a greater degree of managed competition. Some of the key steps expected to emerge in the near future include:

Functional payments across the entire episode of care (rather than on the basis of consultation/enounter) for specific conditions (mainly diabetes and cardio-vascular diseases).

The aim: to encourage GPs and specialists to work together on ensuring the highest and most cost-effective care, and provide health insurers a more active purchaser role in GP care.

Improved DBC system for hospital care by virtue of which diagnoses and treatments will be translated into so called ‘care products’. These would be based on ICDten specialty-specific protocols, and result in just 3,000 care products rather than the current 30,000 DBCs – with a multitude of specialty overlaps and gray zones. The new system would make it easier for providers and insurers to negotiate on the price of care products and the quality of delivered care.

Meanwhile, one of the loudest alarm bells seems to be a looming shortage of healthcare personnel, especially in certain categories. Although more recent figures are unavailable, in 2004-2006, announced vacancies in the healthcare sector increased by 42 percent. 25 percent of these were believed difficult to fill, up from 14 percent in 2004.

Endorsing such concerns is a survey in 2008, which found just 55 percent of nurses and caregivers believing there were enough personnel to guarantee safety. In 2004, the figure was 70 percent.

�