HealthManagement, Volume 5 / Issue 2 / 2010

Author:

Tosh Sheshabalaya

HIT

Austria’s Ausgedinge health and pension system for farmers and miners dates back to the Middle Ages and is considered by some to be the world’s oldest welfare organization. The country’s healthcare system is marked by a deeply-ingrained federal culture, dating back to the 130-year old ‘Mittelbare Bundesverwaltung’ (indirect federal administration) which assigned responsibility, from the Federal Minister through the provincial Governor to district and local health officials.

Distribution of Roles and Responsibilities

Austria’s healthcare system is complex, with cross-stakeholder structures at the federal, Länder (provincial) and local government levels.

The federal government has a central role in the healthcare system, above all in terms of providing overall strategic direction and service quality assurance. Towards this, the federal Ministry of Health and Women (BMGF) is assisted by a number of high-powered advisory boards, commissions and institutes. Key bodies include the Supreme Health Council (Oberster Sanitätsrat) with 30 members from the medical scientific community; a 27-member Structure Commission with national and regional politicians as well as healthcare policy experts; and the Austrian Federal Health Institute (Österreichisches Bundesinstitut für Gesundheitswesen, ÖBIG).

Nevertheless, as far as hospitals are concerned, the passage of laws and their implementation rests with the nine provincial governments.

Public Health Services

Public health services cover epidemiology, preventive health, infant-and-mother care, and school services. These are delegated by provincial governments to local authorities.

The work of the public health service is mainly carried out by district medical officers. Their number has remained at a level of about 300 in recent years, and 30,000 and 60,000 inhabitants each. The district medical officers are assisted by chemists, microbiologists and psychologists, food safety authorities, legal experts and social workers, speech therapists, etc. Their major source of support, however, consists of qualified nurses, who provide appraisals in hospitals, old-age homes and institutions for longterm care.

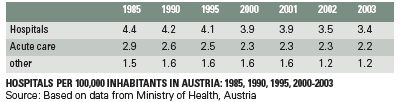

Hospitals and Beds

There has been a steady decrease in the number of both hospitals and beds in Austria over the past 25 years. In 2005, there were about 65,000 beds in 260 hospitals. This represents a fall by about 15% since 1980 in the number of hospitals (some 50 in total), and a sharper 28% decline in bed numbers over the period. As elsewhere, the bulk of cuts has been in the public sector. Bed numbers in private facilities, on the other hand, have grown.

About 40% of Austrian hospitals (110 in total) are general hospitals. These are larger facilities (accounting for over 60% of beds) and are predominantly operated by the Länder; the federal government and local governments own about 10 hospitals each.

One-third of hospitals (95) are specialist facilities, with a similar share in total bed capacity. The rest consist principally of sanatoria (35) and long-term care/convalescence units (20).

In terms of ownership, about half all hospitals (130) are public hospitals. These consist of both public (State) and private non-profit acute hospitals. Approximately 20% are owned by private profit making entities, 15% by religious orders and trusts, and the remaining 15% by insurance and pension funds.

Bed capacity at public hospitals in Austria amounted to 45,000 beds (or about 70% of the total), making them, on average, significantly larger than private forprofit hospitals. Given the dominance of Länders in ownership of public hospitals, they also account for the bulk of beds. Nevertheless, the density of bed distribution in public hospitals is pyramidal. 60% of hospitals have fewer than 200 beds, 25% have between 200 and 500 beds, 7% had 500 to 1,000 beds. Just 9 hospitals (led by the major university teaching hospitals of Graz, Innsbruck and Vienna) had over 1,000 beds each.

At the other end, only 8-10% of beds are provided at private hospitals, although their share in the total number of hospitals is 2-2.5 times higher.

Healthcare Financing and Reimbursement

Given its diffuse structure, modern Austria’s healthcare system is financed in a complex manner by its various stakehold-ers. About half of all healthcare financing is borne by the social health insurance system, a quarter by the State (federal, Lander, and local governments) and the remaining quarter through private payments. The latter factor results in Austria ranking among the lower third of EU countries in terms of public share in healthcare expenditure.

Except for the jobless and casual workers, health insurance (through one of the country’s 21 health insurance funds) is mandatory for all Austrian residents.

The compulsory insurance system covers those directly insured, as well as their family members and children. It extends from coverage of services to cash payments – for inability to work, as a result of illness, disability, or when preventive care is used.

Contributions to the funds are based on occupational status and/or place of residence. As a result, there is no competition between health insurance funds. Health insurance funds are responsible for payment of service providers. In most cases, terms are established with service providers on a contract basis. The use of health services provided by the mandatory health insurance system is independent of contributions.

Reforms since the late 1990s have resulted in a move away from integrated care provision towards a supply model, focused on decentralised contracts with all service providers.

In the outpatient sector, in particular, these contract relationships are almost exclusively shaped by health insurance funds and private service providers (the latter obtain two-thirds of their revenues from the funds and federal grants).

In the inpatient sector, however, financing and services provision continues to reflect the heritage of the integrated provision model, and is regulated within the framework of Article 15a of the Austrian Federal Constitution. Each Länder specifies a list of ‘Fund Hospitals’. These have a statutory requirement to admit and provide healthcare to all patients. In return, they receive subsidies from public sources for investments, maintenance and running costs.

Meanwhile, since 2002, Austria’s private- sector hospitals have become eligible for financing support for inpatient services via a fund called PRIKRAF (Private Hospitals Financing Fund). PRIKRAF makes payments to private hospitals on a performance-and quality-oriented basis known as LKF (Leistungsorientiertes Krankenanstalten-Finanzierungssystem or Performance Related Hospital Financing System), which is essentially an Austrian DRG model.

Private Spending

Co-payments account for about 21% of healthcare spending in Austria. They take the form of both direct co-payments (contributions for benefits covered by social insurance) and indirect co-payments (outof- pocket payments for private insurance in-patient cover). The share of the former is smaller, but has been rising steadily, from 6.5% of total health spending in 1995 to 7.3% in 2000 and are close to 8% at present. Indirect co-payments, on the other hand, have seen a fall in share, from 14.6% in 1995 to 14.1% in 2000 and an estimated 13% at present.

Healthcare Staffing

The bulk of healthcare staffing in Austria (over 80%) is concentrated in public hospitals. In 2005, the number of people working in the healthcare sector was about 175,000, or 5.6% of total employees in the country.

Physician density in Austria is in line with the EU average, at about 3.8 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2007. This is a significant increase from 1990 (3 per 1,000) and 1980 (2.3), when the level was 25% below the EU as a whole.

Of the country’s total of 40,000 physicians, about 30% are GPs.

The ratio of nursing staff, traditionally much lower than the EU average, doubled between 1980 and 1995 to 6 per 1,000 inhabitants, and has since risen to 7.4 in 2007; this is however stll half that the level in neighbouring Switzerland.

Physician Payment

60% of Austrian physicians work in individual capacities for outpatient services, while 40% have contractual relationships with one or more of the health insurance funds. Fees are established by routine negotiations between the funds and the physicians’ chambers.

Physicians can obtain additional income by treating private patients in public hospitals.

According to estimates made by the Austrian Physicians’ Chamber in 2003, gross initial pay for physicians amounts to around 50,000 Euros per year; after 10 years experience, this reaches 75,000 Euros.

Hospital Admissions: Europe’s Highest

According to figures from the European Health for All database (2006), Austria’s hospitalisation rate is 28 acute cases per 100 inhabitants, which makes it by far Europe’s highest (three times over that of the Netherlands’ 8.8 and well over the EU average of 17.5). The gap has, furthermore, increased since the 1980s.

The average 5.7 day length of stay in Austrian acute hospitals in 2007, on the other hand, is far closer to the EU average, and considerably below 7.8 days in neighbouring Switzerland.

The occupancy rate, at 76.2%, is slightly below the EU average of 77.5%, and has moreover fallen (unlike the latter) from almost 81% in 1980.

Outlook For the Future

One of the most notable aspects of the healthcare system in Austria is its relatively early response to the specific problems associated with an aging population, principally in the shape of legislation dating back to the early 1990s.

In 1993, a Long-Term Care Law stipulated that long-term healthcare be financed almost wholly from the federal budget. Longterm care has, however, seen a steady decline over the years, from about 10% of all healthcare spending in the early 1990s to 7.5% at present. Federal cooperation instruments are designed to ensure the uniformity of entitlement criteria and quality standards for institutions in this respect.

Nevertheless, a level of vagueness in separating acute and long-term care in the inpatient sector remains. One indicator is the establishment of ‘acute geriatric’ departments in the country, and the charging of a flat rate per case for geriatric med.