HealthManagement, Volume 11, Issue 5 /2009

Healthcare markets are traditionally perceived as arenas characterised by “rationalised” state regulations that aim to fulfil four key goals of healthcare systems: equity, efficiency, effectiveness and patient satisfaction. Due to this fact, both the supply and the demand sides can be regulated. Voucher schemes can be seen as those instruments stimulating the demand side; the purchasing power is transferred to the client. This article will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of vouchers in healthcare systems with public insurance systems like the Czech Republic, taking into consideration the points of view of the key actors involved.

Theoretical Framework

Vouchers are typically used in education or social systems. One of the earliest suggestions for government use of vouchers was put forward by M. Friedman in 1962 as a way to fund education without excessive government intervention in the schooling market. Vouchers typically transfer purchasing power to the client. The aim is to empower the household to pick the school (public or private) that best suits parental preferences and the child's needs and to allow low-income families access to private schools. It therefore places the onus on the school to provide quality education, and to attract the household's voucher. The result is that schools perceived as ‘high quality’ attract more students, receive many vouchers, and prosper.

“Health” vouchers could be used as a tool to increase the choice of providers for patients or targeting subsidies to the poor and/or high risk/vulnerable groups for example. Vouchers may provide a means of funding healthcare services. However, using vouchers in the healthcare sector seems to be more problematic than in the education system; the history of well known health market failures to name one problem. Patients’ choice of healthcare providers is also limited due to capacity problems (e.g. waiting lists), local and time service availability, and inability to evaluate the quality of service.

The Czech healthcare system is a public insurance system with a low level of copayments. Therefore, the price information has no meaning for decision-making. The exceptions are dental services, but information about prices is generally inaccessible. As a result, patients’ opinion about quality is based on personal experience and “public opinion”. In fact, if a provider (hospital or physician) is considered as a top quality provider then they become overloaded and experience capacity problems.

So, theoretically there are crucial questions important for the evaluation of the advantages of vouchers:

Who is eligible for the voucher?How is the voucher distributed and what are the costs of distribution?

What service is demanded through the voucher and who (which institution) is obliged to reimburse the value of the voucher?

Are all healthcare providers obliged to accept these vouchers (public as well as private provides) or only selected providers?

Studies on the subject often introduce cases from countries where a part of the population have limited access to basic healthcare services, generally due to lack of financial resources. Some authors consider the universal voucher system as a way of resolving current problems in the US healthcare system, but could vouchers be a suitable tool for public insurance system?

In our previous paper, “Voucher schemes - threat or opportunity for the Czech Healthcare sector?” we concluded “that vouchers in the healthcare sector under peculiar conditions of the Czech Republic have very limited potential to use. There is no definition of standard services (covered by the public insurance) and above standard services (paid by the patient) and each “necessary” service is theoretically available for each patient (statement – part of description of the Czech healthcare system). The patient has a right of free choice of specialist as well as facility. Because of that, we could expect that patient choice of provider would be the same with or without vouchers. Vouchers have no impact on waiting lists or other capacity problems”.

Vouchers seem to be suitable in three cases:

1. Vouchers for “above standard” and “preventive” care, to encourage responsible behaviour by patients. However, the same function should fulfil “the benefit system” provided by the health insurance companies.

2. Vouchers for socially excluded groups – distributed by NGOs or state institutions in paper form, they can be more enticing than usual “benefit programmes”. However this possibility represents some kind of fiscal illusion.

3. Vouchers for illegal immigrants – distributed by NGOs (supported by the government) represent tools for support to the excluded vulnerable group.

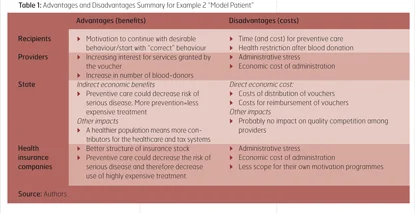

The following section focusses on the advantages and disadvantages of vouchers from the point of view of each respective actor involved. The analysis is based on the assumption that healthcare has defined “standards” of services covered by public (private) insurance. The advantages and disadvantages of voucher scheme are discussed using two examples. Cases chosen as the examples could be considered as “less” problematic rather than general vouchers system implementation.

Aim and target group: Healthcare for people in financial distress (as defined by law). Considered problem of this group: Patient (member of this group) has shortage of money for visiting a physician (fee for visit) and also for buying medication (patient’s co-payment). Considered solution: Vouchers allowing free visits to physicians; vouchers guaranteeing free access to medication (group of medications defined as basic for given illness). Actors influenced by the vouchers provision: Physicians; pharmacists; recipients; state. Distributor of voucher: Social security institutions.

Crucial condition: There is no chance to trade with vouchers or exchange them for cash.

Example 2: Vouchers for “Model Patients” Aim and target group: Provide extra benefit for patients who keep all obligatory prevention procedures; or vouchers for blood-donors. Considered problem of this group: Motivate all insured in the healthcare system to keep up preventive care; or motivate people to become blood-donors (blood-donors received no monetary reward in the Czech healthcare system). Considered solution: Voucher for extra services (exactly defined – e.g. spa, massages, free preventive care which is normally provided only as paid service (e.g. whole body examination as a prevention of cancer). Actors influenced by the vouchers provision: Providers; recipients; state; health insurance companies. Distributor of voucher: Health insurance companies, transfusion centres. Crucial condition: There is no similar system of motivation (i.e. benefits form health insurance companies).

Conclusion

Although introduced examples where only theoretically discussed, we can conclude that the voucher system has (limited) potential for use. From the providers’ point of view there is a lack of advantages for voucher implementation. Vouchers cannot be implemented without increasing administrative stress. Providers perceived as the top quality bearers could have problems with over-supply. So providers are not motivated to support voucher implementation, however they are considered as the group whose support is crucially needed for successful implementation of any public policy. For the successful implementation of a voucher scheme, support from providers and health insurance companies (HICs) is crucial. Providers have no direct benefits from voucher schemes and HICs (aside from above mentioned benefits) could perceive the vouchers as a tool for restricting their competition area and decreasing their autonomy. But how to increase support from providers? The answer could be simple: Advantages for providers should be increased. In other words, providers should benefit from the system like the other actors. The second question is how to increase support from the health insurance companies. HICs’ support depends on whether the benefits for providers could be perceived as tool against competition among HICs. Gathering support from HICs means that sufficient room for competition has to remain.

From a managerial point of view, the voucher system could work if administrative obstacles were eliminated and the whole process was clear and simple, from voucher distribution, utilisation by the recipient, to reimbursement of vouchers. We suggest the following principles valid for a public insurance system with low patient co-payments like the Czech healthcare system:

- Distribution of vouchers should be the responsibility of NGO’s and/or of state institutions (e.g. social security institution) but all vouchers must have the same paper format and work on the same principle. Utilisation of health service by the recipient should be the same as for patients without vouchers: Vouchers work like money. Inspiration should be taken from food-tickets system for employees (the tickets are distributed by employers and accepted in most restaurants).

- There should be no possibility to trade vouchers.

- Reimbursement should be “provider friendly” with no extra waiting time for voucher reimbursement. In fact, as a benefit for providers accepting vouchers, better reimbursement time conditions or higher level of reimbursement could be proposed. On the other hand, such support to providers could induce other problems in the healthcare system, particularly the attitudes of HICs.

As we have illustrated, implementing a voucher system for healthcare could bring benefits for all relevant actors involved. However, the scheme is not without disadvantages and should therefore be approached with caution. Inappropriate implementation of such a system could create friction between actors or have no real impact on possible recipients’ health.

![Tuberculosis Diagnostics: The Promise of [18F]FDT PET Imaging Tuberculosis Diagnostics: The Promise of [18F]FDT PET Imaging](https://res.cloudinary.com/healthmanagement-org/image/upload/c_thumb,f_auto,fl_lossy,h_184,q_90,w_500/v1721132076/cw/00127782_cw_image_wi_88cc5f34b1423cec414436d2748b40ce.webp)