HealthManagement, Volume 14, Issue 3 /2012

Introduction

Portugal is located in the south-west of Europe. The mainland has an area of 91 900 km2; the country also includes the archipelagos of Açores and Madeira. The capital of Portugal is Lisbon and the official language is Portuguese.

The total population has seen a 5% increase over the last decade. While in the 1970s only 38.8% of the population lived in urban areas, this rose to 58.2% by 2006. Most of the population is concentrated in two large metropolitan areas: Greater Lisbon (with approximately two million inhabitants) and Greater Oporto (with approximately 1.2 million). The number of births has been declining steadily since the 1970s and the average age has been steadily rising.

In terms of production and income, in 2010, total Gross Domestic Product was 272.4 billion USD (curr. PPPs). In terms of health status, and beyond the crude death rate shown above, in 2009, life expectancy at birth was 79.5 years (76.5 years for males, 82.6 years for females). This result places the country just above the OECD average.

It is also the result of a continued and marked improvement over the last five decades. Both sexes have seen similar improvements. Women live on average six years more. Portugal has also had over the last four decades one of the largest reductions in infant mortality rates among OECD member countries.

The Organisation of the Healthcare System

The Portuguese healthcare system is a national health system founded in 1979. It was formed mostly based on structures already in place (hospitals and primary care centres) but not necessarily organised as an integrated set of providers.

In the last few years, reforms have seen both primary care centres and hospitals grouped both horizontally and vertically, forming in this case local health units, in order to improve management, efficiency and quality.

As is typical in Beveridge influenced systems, the Portuguese NHS and therefore its hospitals have been financed mostly with funds from general taxation. Healthcare costs have grown consistently above both the inflation rate and the increase in GDP.

Primary care and secondary care are supposed to work together in articulation. As is often the case, transition of both patients and information between the two levels is not as smooth as desired, raising issues in terms of coordination and continuity of care. More recently, a third level, longterm care, has been added to the equation. Longterm care is expected to reduce the need for longer hospital stays but beds are still insufficient.

Financing

In 2008, the latest year available, total health spending accounted for 10.1% of GDP. This placed us, in 2009, above the OECD average of 9.5%. Portugal has also typically had a slightly higher percentage of private financing than other OECD countries. This amounted to 2,508 USD per capita, after adjusting for purchasing power parity. Comparing total health expenditure per capita with countries’ GDP per capita, there seems to be a positive correlation between the two. Portugal is well within this trend.

Human resources

Portugal currently has 3.8 physicians per 1,000 population, but this data refers to all physicians who are licensed to practice and thus includes doctors not actually practicing. In any case, this result places us above the OECD average. This has been the result of a steady increase over the last five decades.

Simultaneously, in 2009, Portugal had 5.6 nurses per 1,000 population. In this, we were below the OECD average, in spite of considerable growth in the past decade.

The country’s ability to form these professionals has indeed increased significantly in the past. We are thus slightly above the OECD average in the first case (albeit with a ratio of graduates to physicians below theirs), and the opposite is true when looking at nurses. In terms of healthcare management, Portugal has had a post graduate course in hospital management for over 40 years now. Taught by the National School of Public Health (http://www.ensp.unl.pt/), it was for a number of years a requirement to enter hospital management; changes more recently to the legislation made this optional rather than compulsory, while simultaneously other schools started teaching health services management, mostly at the postgraduate level.

The Portuguese Hospital System

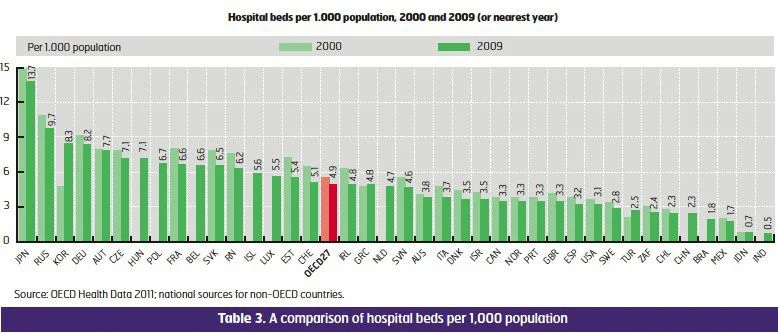

Most hospitals and hospital beds in Portugal are public. Both numbers however have been decreasing in recent years. The number of hospitals has decreased mostly through mergers, with several hospitals forming hospital centres, under a common executive board. The number of beds has decreased mostly as part of an international trend, associated with more effective and efficient treatments and the move of a number of activities (namely surgical) to ambulatory care. In 2009, there were 2.8 acute care hospital beds per 1,000 population.

A look at the number of acute care beds suggests these were less affected than other types of beds. Occupancy rate of curative (acute) care beds has for the past decade been stable around 72 %, with several experts arguing for the need to reduce the number of beds as a way to increase this rate. The average length of stay in 2009 was 5.9 days. This too has dropped significantly over the last few decades.

Current Concerns

As is common elsewhere in the developed, western world, Portugal faces the problems brought by an ageing population, with increased incidence and prevalence of chronic conditions and multimorbidity. The Ministry of Health is thus currently insisting on health promotion and disease prevention as a means to ensure the overall sustainability of the system.

Eight clinical and health promotion areas have been identified as priorities: Diabetes, HIV infection and AIDS, tobacco consumption, healthy eating, mental health, oncology, respiratory diseases, and cardio and cerebrovascular diseases.

The current government is keen on promoting actions on lifestyle changes, with special focus on diet and exercise, while reducing the consumption of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs. Some of these require intersectoral policies. Target populations include the young and the elderly, with healthy and active ageing as an objective.

In organisational terms, governance relies both on the national level, for policy and budgeting, and also on five regional health administrations. Access to the system is still a problem in some areas, with waiting list and waiting times mostly for elective surgery, outpatient visits and diagnostic tests. The last few years however have seen a number of specific programmes to try to overcome this situation.

In recent years Portugal has also shown particular interest in the quality of healthcare provided. There is a national strategy for quality in healthcare approved in 2009 and the country has participated in global safety programmes led by the WHO, for instance.

We are also currently in the process of transposing to the Portuguese legislation the directive on cross-border care; as a part of this process, the Ministry is working on the definition of referral centres to integrate European reference networks.

All actions taken by the government follow a national health plan, stretching from 2012 to 2016. The previous plan (2004-2010) was very positively reviewed by the WHO (http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/83991/E93701.pdf). Internally, comprehensive reviews are being undertaken in primary care, emergency services and long-term care, based on the advice of national experts.

The main current issues with the Portuguese national health system are necessarily related to the current economic crisis the country (and Europe in general) is going through, and the need to ensure the system’s sustainability. In the context of the global economic crisis, the country and the healthcare system are currently under pressure to be more efficient while ensuring access and quality. The healthcare sector is thus undergoing some reform, with specific efforts directed at hospitals. These focus around 8 axes:

1.Implementing a more coherent hospital network

Specific measures include the redefinition of the network of hospitals, given the recent formation of several hospital centres, grouping hospitals, and the existence of a number of referral networks (specialty-based) that need coherence and updating.

2. Defining a more sustainable financing policy

Specific measures include the development of costing systems and improving the benchmarking efforts between hospitals.

3. Integrating care to improve access

Specific measures include the improvement of referral criteria between primary care centres, hospitals and long term care.

4. Making hospitals more efficient

Specific measures include implementing and monitoring clinical guidelines and increasing ambulatory surgery rates.

5. Ensuring quality as a major trait of hospital reform

Specific measures include reducing the rates of hospital acquired infections and the rates of cesarean sections.

6. Investing in information systems as a sustainability factor

Specific measures include implementing the electronic health record and guaranteeing the validity of all information in the system.

7. Improving Governance

Specific measures include celebrating management contracts with the boards and assessing board performance.

8. Strengthening the role of citizens

Specific measures include making hospital benchmarking public and making patients aware of healthcare costs. The Ministry of Health believes this to be the only way to make the Portuguese healthcare system sustainable in the face of one of the biggest economic crises seen in recent years, while at the same time improving its effectiveness, efficiency, safety, fairness, timeliness and patient-centeredness.

References:

References available upon request, [email protected]