HealthManagement, Volume 14, Issue 1/2012

The rapid growth of pharmaceutical expenditure driven by changing demographics, strict clinical targets, rising patient expectations and the continued launch of new expensive drugs has become a contentious issue in the healthcare sector. New expensive drugs include new biological drugs marketed at considerably higher costs than previous standards, which now account for over 50% of in-patient drug costs among hospitals in Marseilles. This is causing concern with expenditure growing at approximately 20% annually leading to rationalisation of other hospital services.

If not addressed, this growth will compromise the European ideals of comprehensive and equitable healthcare exacerbated by the limited health gain of many new drugs, including new cancer drugs, despite high prices (Table 1). In their assessment of the value of new drugs between 2001 and 2007, the Transparency Commission in France concluded that only 13% had ‘major’ or significant health gain with the majority (78%) having only minor or no improvement. The Scottish Medicines Consortium, an HTA body established in Scotland to give rapid advice on the clinical and economic value of new medicines, in their analysis of 281 new products and indications between 2002 and 2008 also found limited health gain, with QALY (Quality Adjusted Life Year) gains averaging just 0.097 years and no more than 12% offering >1year.

Stakeholder Responses

These concerns led to activities among European stakeholders, including healthcare managers, to further improve prescribing efficiency. They include:

- Greater co-ordination of national, regional and local activities pre and post launch to improve the ‘managed entry’ of new drugs;

- Raising concerns with ‘risk sharing’ arrangements (Table 2) as pharmaceutical companies seek new ways to enhance the value and/or reduce the budget impact of their new drugs;

- Formularies/ guidance in hospitals along with benchmarking of subsequent physician prescribing; and

- Greater co-ordination between hospitals and ambulatory care of drugs prescribed to maximise overall efficiency.

Improving the Managed Entry of New Drugs

Clinical pharmacologists and pharmacists are also playing an increasing role to optimise the managed entry of new drugs to ensure available resources are used wisely.

These activities include:

- Undertaking early detection of new drugs likely to have a major budget impact. This process is known as ‘Horizon Scanning’, and is increasingly linked to all decision-makers in healthcare.

- Forecasting of drug expenditure in each major ATC class. This includes an assessment of the likely role/ patient population for new drugs based on their anticipated net benefits in all/ sub-populations and possible prices, along with assessments of the financial consequences of new guidelines as well as current products likely to lose their patent during the coming years.

- Performing critical evaluations of new drugs pre-launch including development of guidelines/ guidance and protocols influencing post launch utilisation. Decisions incorporated into regional guidance/ hospital formularies. This includes assessment of comparators, doses and endpoints especially if concerns with unproven surrogate measures.

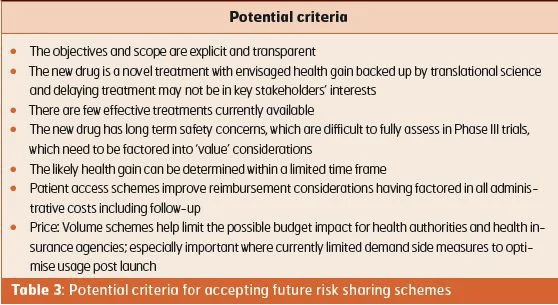

- Developing guidance for accepting/ assessing future risk sharing arrangements for new drugs (Table 3).

- Retrospective assessments of the benefit of new drugs in practice using observational data, typically registries. This is prevalent for new expensive biological products in Italy and growing for instance in France, e.g. natalizumab in multiple sclerosis, and Sweden.

- Continuous monitoring of prescribing and expenditure of new drugs in hospitals and primary care post launch with further educational activities if needed; acknowledging that it may be difficult to obtain accurate drug utilisation figures in hospitals.

Ongoing Activities with Existing Drugs

Best practices include:

- Providing clear updated recommendations for the treatment of common diseases, preferably valid for both primary and secondary care.

- Follow-up of prescribing guidance in practice with educational and other activities to enhance adherence. This includes continuous monitoring and subsequent feedback to prescribers and healthcare managers.

- Close working between counterparts in hospital and ambulatory care to optimise prescribing efficiency. This can include active therapeutic substitution.

- Aggressive contracting in hospitals.

Examples include University College Hospital, who recently instigated a drug substitution policy for ARBs. All admitted patients prescribed other ARBs than generic losartan for hypertension are automatically switched to losartan, unless intolerance concerns, as all ARBs seen as interchangeable. Any patient prescribed another ARB for heart failure also switched to generic losartan with doses increased if less than maximal doses currently prescribed. Similar switch programmes are in operation across all sectors in the UK saving an estimated £20mn/ month (24mn) if fully implemented.

Clinical pharmacologists, hospital pharmacists and pharmacists working for health authorities are increasingly working together to standardise common drugs to maximise prescribing efficiency across both sectors. This is driven by more standard drugs losing their patents, with estimated global sales of up to $US100bn/ year of products likely to lose their patent between 2008 and 2013. Failure to co-ordinate activities increase costs and/ or limit potential savings in reality. Examples of the former include:

- In Scotland, contracts for hospitals increasingly take account of efficiencies across both sectors. This built on historic examples, e.g. Isosorbide Mononitrate MR tablets were heavily discounted in hospitals although costs in the community were approximately 11 euro/month/ patient higher than the lowest cost product (factor of 30). This resulted in some Health Boards working outside the contracting system to maximise whole system efficiencies until changes were made.

- The Ministry of Health in Lithuania endorsing the continued prescribing of patients’ medications in hospitals provided patients with chronic conditions have been on the medication for at least a month. This initiative was introduced to combat possible switching in hospitals to more expensive medications, which were typically donated by companies to enhance their prescribing post discharge.

- Separate guidance on suggested common drugs (“Wise Drug List”) for out-patient hospital specialists (in operation since 2005), building on the guidance for primary care physicians. This includes for instance nutritional supplements, parenteral antibiotics and cytotoxics. The driving force being the recognition that hospital specialists heavily influence prescribing in ambulatory care.

Activities used by clinical pharmacologists and pharmacists working on behalf of health authorities to improve the quality and efficiency of ambulatory care prescribing include the 4Es (Education, Economics, Engineering and Enforcement). Recent research has shown that multiple and intensive interventions are more successful than single interventions (PPIs and statins), although prescribing restrictions can be successful on their own. Expenditures for PPIs and statins (/1000 inhabitants/ year) varied over tenfold between patient populations depending on the extent and the intensity of initiatives undertaken. Concurrent with this, a recent ecological study has shown no appreciable impact on care whether patients are prescribed formulary drugs such as generic simvastatin or non-formulary drugs such as rosuvastatin; however, appreciable differences in expenditure.

Conclusion

Clinical pharmacologists and hospital pharmacists can appreciably enhance the quality and efficiency of prescribing of both new and existing drugs across all sectors. Failure to act and/or get involved will increase the prescribing of expensive patented drugs where less costly alternatives are available, without affecting care, and compromise the ability of European countries to continue to provide comprehensive and equitable healthcare.

References:

References are available online or upon request: [email protected]

![Tuberculosis Diagnostics: The Promise of [18F]FDT PET Imaging Tuberculosis Diagnostics: The Promise of [18F]FDT PET Imaging](https://res.cloudinary.com/healthmanagement-org/image/upload/c_thumb,f_auto,fl_lossy,h_184,q_90,w_500/v1721132076/cw/00127782_cw_image_wi_88cc5f34b1423cec414436d2748b40ce.webp)