HealthManagement, Volume 16 - Issue 4, 2016

The Canadian medical system has integrated several

paradigm-shifting transformations in the past two decades, not the least of

which include quality improvement a nd patient-centred c are. With each

transformation there has been a concurrent benefit to patients, leading to

improved patient outcomes and more effective systems of care. In this context

it would be reasonable to then ask, why are Canadian Indigenous patients so

sick?

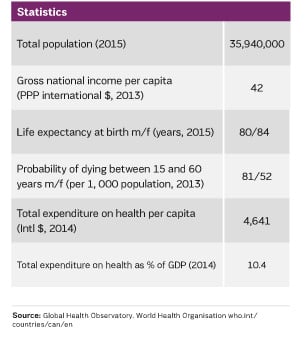

Canadian Indigenous patients—those of First Nations, Metis and Inuit descent—continue to suffer much higher rates and severity of disease when compared to other demographics. HIV rates on Saskatchewan reserves are higher than many African nations. Infants in Nunavut suffer the highest rates of respiratory disease in Canada. The incidence of diabetes is three to five times higher. Itis factual that significant health disparities exist between Indigenous patients and other Canadian demographics. We are also observing that these disparities are not static. In many areas they are widening and in some cases accelerating.

See Also: Dilemma of Migrant Healthcare Workers

Analysing the causes behind this ongoing health crisis have taken us in many different directions. More recently, the Social Determinants of Health have provided a useful context to frame these causes into poverty, education, early childhood development, food insecurity, racism, among others (Mikkonen and Raphael 2010). As health leaders however, it is difficult to reconcile how to impact areas clearly out of our scope of influence. For example, how does a health leader impact poverty from within the confines of the health system?

Taking a systems approach can have much more utility. In Canada, there are actually many different types of health systems. The most well-known is Medicare, a system funded by both federal and provincial levels of government but administered by each respective province. Lesser known health systems include those both federally-funded and administered. These include refugee health, the military, the prison system and indigenous health. Despite the oft-repeated statement that providing healthcare is a provincial responsibility, the federal government clearly is very much in the business of healthcare.

When comparing the design of all these various health systems, there are some surprising insights. In Medicare, various types of legislation create accountabilities that enable patient rights. The Health Acts of each province establish a baseline of services that must be provided: services such as emergency care, laboratory services, diagnostic imaging, among others. Other acts include those that govern health quality, health professions, etc. Legislation creates fiduciary duty. Fiduciary duty necessitates defined processes.

None of these Acts exist federally. Without legislation, it is difficult to create clear fiduciary duties and define processes. Many federal programmes are thus dependent on policy; in many cases this is very wellwritten. For example, the military health system has overcome the legislative gap regarding health professions by establishing contractual relationships with Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons across Canada. Recognising that it would be unreasonable to create an independent regulatory framework to govern health professionals within the federal military system, the military system has created a workaround. Other legislative gaps are overcome in a similar manner with the other federally-administered systems of care. Not so with indigenous health.

There is no baseline of healthcare services on reserves. Instead

the Indigenous health system exists as a collection of various time-limited

funding proposals, usually selected from an à la carte buffet of programme

options. Instead of 24/7 coverage, we discuss “doctor days” and “nursing days.”

The system purposely schedules lack of access to medical professionals. For this

reason, access can fluctuate widely between indigenous communities. Consider

having no access to healthcare providers as an expected component of health

system design.

Credentialing, quality improvement, resuscitative equipment, emergency medication, continuity of care, as well as the many other health system components we take for granted are also very inconsistent. How can a health system be built without the proper building blocks?

Canada is in the midst of a broad reconciliation process with its indigenous peoples, triggered through a court-mandated Truth and Reconciliation Commission that published its final report in 2015. Regarding health transformation, National Chief Perry Bellegarde of the Assembly of First Nations states: "the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action on health create a pathway for innovation and collaboration that will transform healthcare and improve the health of First Nations people in Canada. This is about supporting First Nations’ priorities based on our health care realities, and finding solutions that draw on the effectiveness of our knowledge and cultural traditions.”

To understand indigenous health realities we can start with acknowledgement that indigenous patients may be sick because we literally aren’t providing them the same healthcare as the rest of Canada.