HealthManagement, Volume 16 - Issue 3, 2016

MAXIMISING THE POTENTIAL OF THE MODERN RADIOGRAPHER WORKFORCE

Successful delivery of radiology and radiotherapy services is reliant upon a multiprofessional workforce capable of delivering high-quality, patient-centred care in a timely and cost-effective manner. In the UK, the traditional relationship between the radiology and radiography professions has changed, resulting in a radiographer with a much-expanded scope of professional practice. Indeed the radiographer role today is far removed from that promoted by of the early radiography pioneers such as Furby (1944) [see quotation].

While there are many professional titles in use across Europe, the European Federation of Radiographer Societies (EFRS ) published its definition of a ‘Radiographer’, following approval by the EFRS General Assembly (EFRS 2011a).

In order to be recognised under this definition, the level of knowledge, skills and competence of a radiographer should be at Level 6 of the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) (EFRS 2014; European Commission 2008), which is equivalent to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) Qualifications Framework (2005) Bachelor level. For this purpose the EFRS definition is:

Radiographers are medical imaging and radiotherapy experts who are professionally accountable to the patients’ physical and psychosocial well being, prior to, during and following examinations or therapy; take an active role in justification and optimisation of medical imaging and radiotherapeutic procedures; are key-persons in radiation safety of patients and third persons in accordance with the “As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA)” principle and relevant legislation (EFRS 2011)a.

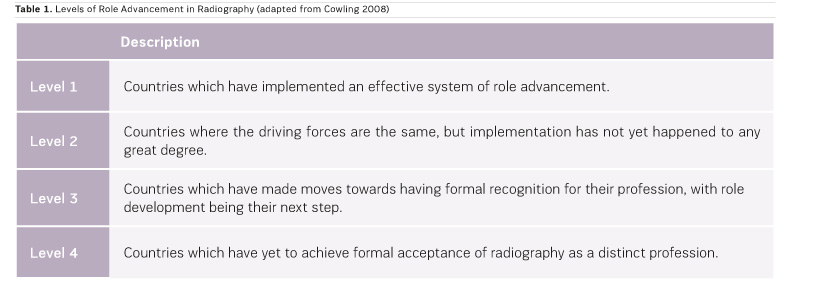

Within this document, the EFRS also identified the term ‘Radiographer’ as the single title at the European level, yet it is clear that the scope of practice of radiographers varies considerably from one country to another. Cowling (2008) offered a global overview of the changing roles of radiographers, suggesting that the UK is unquestionably the world leader in advanced practice. She outlines four different levels of role advancement (Table 1) with the UK sitting at Level 1 followed by countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan, South Africa and New Zealand, together with a growing number of European countries (based on more recent EFRS data) sitting at Level 2. Despite 90 percent of EFRS national societies stating that they actively promote and support radiographer role development (EFRS 2015a) there remains limited evidence of the successful implementation of advanced practice across many countries. The majority of European countries remain at Level 3.

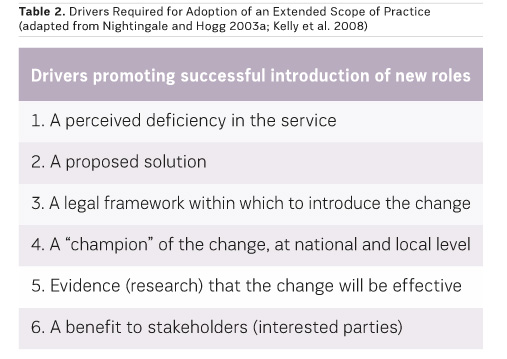

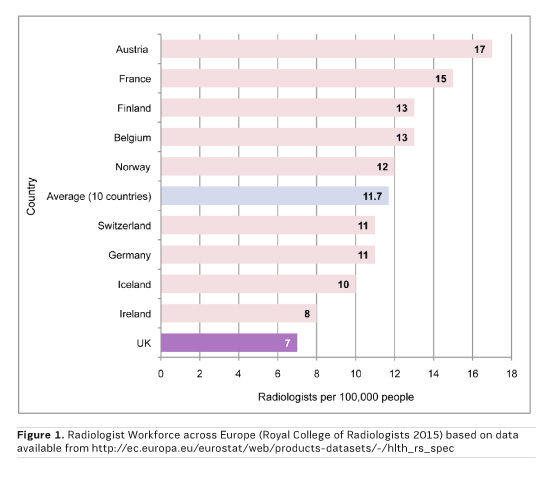

Analysis of a number of historical role developments suggests that a range of overlapping drivers are necessary to ensure widespread adoption of an extended scope of practice (Table 2). Arguably, the most important driver is a significant and long-standing service need. In the UK there has been exponential growth in demand for radiology, alongside a shortage of radiologists and increased public expectations. A 2015 report showed the stark differences in the radiologist workforce in the UK (7 per 100,000 population) compared with the European average (11.7); indeed, the UK has less than half of the radiologists/population ratio of Finland and France (RCR 2015) (Figure 1). The European Society of Radiology (2009) also published data indicating a European average of 10.4 with national figures ranging from 0.15 to 21.5 per 100,000).

From the UK data, the radiologists appear to be working to capacity using a limited physical resource; the UK has less than half the number of CT and MR systems and radiotherapy treatment systems per million population compared to many European countries (National Audit Office 2011). However, they are performing more scans than these other countries, with less equipment, whilst also coping with a 10-12% increase in CT and MRI procedures every year (NHS England 2014). Maximum utilisation of limited equipment and staffing resources has only been possible in the UK with the routine adoption of radiographer advanced practice. That is not to say that all hospitals have embraced advanced practice fully; indeed many teaching hospitals have been slower to embrace skills mix, probably due to higher radiologist ratios. A review of the successful adoption of one particular advanced role (gastrointestinal imaging) acknowledged the vital role of nationally-recognised gatekeepers: in this case radiologist champions, promoting radiographer role development both within and beyond radiology (Nightingale and Hogg 2003b). However, it is clear that for the vast majority of National Health Service hospitals within the UK, radiographer advanced roles are now completely embedded in service delivery. Even with higher numbers of radiologists in training, it is difficult to imagine radiology departments removing these posts, assuming they deliver high-quality patient care.

Confusing Range of Terminology

One of the difficulties in interpreting the success or otherwise of the advancing role of the radiographer is the range of terminology that is used, often interchangeably, which may have created confusion (Hardy and Snaith 2006). Role developments can be an expansion of practice, whereby radiographers take on new duties that confer the same level of practice and responsibility; these role developments can become part of the normal scope of practice of radiographers over time. Role extension refers to roles which were traditionally undertaken by other professionals, usually radiologists. Such roles may result in a higher level of practice and increased responsibility and autonomy. Hardy and Snaith (2006) argue that the extended role is a natural development for a professional radiographer.

Until recently, a lack of clarity has persisted around a definition of advanced role in the radiography context. Early attempts to define radiographer advanced practice roles were made by Nightingale and Hogg (2003a; 2003b) and Hardy and Snaith in 2006. These authors suggest that ‘advancement’ does not purely indicate an increase in the nature or complexity of skills; a radiographer who performs an extended role, whist having increased responsibilities, will not necessarily be working at an advanced practice level.

T o perform at this higher level (as expected of an advanced practitioner) would require them to be actively developing practice for the benefit of their patients. While expert clinical practice in a clearly defined area is a key component of their role, advanced practitioners should also demonstrate:

- Delivery of specialist care to

patients;

- Contribution to, and evaluation

of, the evidence base to develop practice ;

- Education and training of other

staff;

- Recognition of knowledge and

expertise – expert resource;

- Team leadership, including

service management and planning. (EFRS 2011b; Hardy and Snaith 2006; Kelly et

al 2008; Snaith and Hardy 2007)

Working Across Traditional Healthcare Boundaries

Advanced practitioners often work across traditional healthcare boundaries, being fully integrated into new care pathways and the multidisciplinary team. This clearly delineates the advanced practitioner from the largely uniprofessional focus of the radiographer practitioner grade. The transition from practitioner to advanced practitioner requires significant investment at the individual, service and organisational level if it is to succeed and become firmly embedded within healthcare practice. To achieve this status requires additional knowledge, skills and expertise, and this is most compatible with Masters level (EQF Level 7) study (SCoR 2005), with evidence of successful integration of advanced clinical competences within a postgraduate framework (Piper et al 2010; 2014; 2015). Lack of formal education has several potential consequences, including lack of transferability between hospitals, reduced recognition, and lack of opportunity for career advancement. Radiographers should be encouraged to see postgraduate study as an essential component of advanced practice (EFRS 2011b), though currently only 39% of educational institutions with a pre-registration radiography programme currently offer Masters programmes for radiographers while only 14.6% offer doctoral programmes (McNulty et al. 2016).

In summary, an advanced practitioner is:

An individual who has significantly developed their role and who consequently has additional clinical expertise in a defined area of practice, accompanied by deep underpinning, evidence-based knowledge related to that expertise. They make appropriate clinical decisions related to their enhanced level of practice, directly impacting on the patient care pathway (EFRS 2011)b.

and is:

...autonomous in clinical practice, defines the scope of practice of others and continuously develops clinical practice within a defined field (College of Radiographers 2005).

and:

... has an essential role in enabling the advancement of innovative practice where this can contribute to improvements in service delivery and quality patient care (EFRS 2012a).

Benefits and Limitations of Advanced Practice

As the interest in adopting radiographer advanced roles grows in many European countries, a clearer picture has emerged about the benefits and limitations of advanced practice in countries which have embraced it (Kelly et al. 2008). There is empirical evidence to demonstrate that radiographers are competent to perform advanced roles, with many studies comparing radiographer performance directly to that of radiologists (Judson and Nightingale 2009; Woznitza et al. 2014; Torres-Mejía et al. 2015; Reid et al. 2016; Moran and Warren-Forward 2016). Evidence of the wider impacts of advanced practice is growing, but more is required (Law et al. 2008; Hardy et al. 2013; Lockwood 2016; Snaith et al. 2015; Clarke et al. 2014). There is also evidence to demonstrate the successful uptake of advanced roles (Price and Le Masurier 2007; SCoR 2012), but few articles consider why advanced practice may have failed to be fully adopted in some regions.

One exception is a recent article by Henderson et al. (2016) that highlights the current status of advanced practice of radiographers in Scotland, which did not compare favourably to the adoption of such roles in the rest of the UK.

Boundaries Between the Professions Begin to Blur and Reposition

As radiographers adopt new advanced roles, the boundaries between the professions begin to blur and reposition. For example, a decade ago there was a clear demarcation between the role of the radiographer in trauma imaging (producing the images) and that of the radiologist (reporting the images), whereas this distinction is now less clear, with 41 percent of UK imaging departments in 2012 employing radiographers to report trauma images (SCoR 2012).

Similarly, radiographers in many centres in the UK are now performing and reporting a range of contrast gastrointestinal procedures (SCoR 2012), yet for some examinations such as CT colonography there is still considerable debate amongst the radiologist community about whether radiographers should be involved in reporting (Boellaard 2012). While radiologists may be concerned that radiographers are encroaching upon their domain, radiographers may have similar concerns about assistant practitioners (non-registered healthcare workers) encroaching on the radiographer scope of practice. One of the concerns regularly expressed is that as roles are delegated by one professional group to another, reduced exposure to practice will lead to a change in the baseline skills of the delegating profession. The ‘expert’ will shift from one profession to another: radiologists will need to be prepared to ‘let go’ of some professional expertise, and radiographers must be prepared to shoulder this increased expectation.

The Radiography journal, which is the official journal of the EFRS and the Society and College of Radiographers, has been the main conduit for dissemination of evidence related to advanced practice, and it continues to engage with the European radiographer community to encourage evidencebased practice and radiographer research and to develop publishing and dissemination skills. Published articles within this and other journals have shown tangible benefits of radiographer advanced practice, including improvements to examination waiting times and report turnaround times with no adverse effects in terms of patient safety and outcomes. Radiographers in the UK have embraced these new opportunities to utilise their skills and expertise—the most highly skilled radiographers are now being retained via a lifelong career pathway, rather than them moving to management or education posts due to a lack of challenging opportunities in clinical practice. While other countries are working towards the adoption of advanced roles, they do not all have the critical drivers that have been apparent in the UK.

Immense Benefits Through Implementation of Advanced Practice

Nevertheless, the benefits to radiographers and their patients could be immense through the implementation of advanced practice across a wide range of areas such as musculoskeletal (MSK) reporting, breast imaging, gastrointestinal imaging, interventional procedures and radiotherapy. For this to happen on a large scale there needs to be a clear professional steer. In the UK, by stating that the modern scope of radiographer practice is “that which the radiographer is educated and competent to perform”, the Society and College of Radiographers (2009) is making it clear that it sees no boundaries to the practice of a radiographer. Similarly, the EFRS as the umbrella organisation for 39 national radiographer societies and 55 educational institutions, representing over 100,000 radiographers and over 8,000 radiography students across Europe, has a role in guiding member organisations. Through its Statements on Education (2012b) and ongoing work on establishing EQF Level 6 (2014) and Level 7 benchmarking documents for radiographers, the EFRS continue to highlight the need for the wider consideration of role development, role extension and advanced practice. Raising the profile of the radiography profession and of radiography education, together with the continued development of its relationship with the European Society of Radiology, are some of the essential ingredients to facilitate this at the European level. However, national and local opportunities to improve patient care and outcomes will always remain the critical driver for the development of the radiographer scope of practice.

Key Points

- As

radiographers adopt new advanced roles, boundaries between the professions

begin to blur and reposition.

- A range of

overlapping drivers is necessary to ensure widespread adoption of an extended

scope of practice.

References:

Boellaard TN, Nio CY, Bossuyt PMM et al. (2012) Can radiographers be trained to triage CT colonography for extracolonic findings? Eur Radiol, 22(12): 2780-9.

Clarke R, Allen D, Arnold P et al. (2014) Implementing radiographic CT head reporting: the experiences of students and managers. Radiography, 20(2):117-20. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from academia.edu/7108151/Implementing_radiographic_CT_head_reporting_The_experiences_of_students_and_managers

College of Radiographers (2005) Implementing radiography career progression: guidance for managers. London: The College of Radiographers. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from sor.org/learning/document-library/implementing-radiography-career-progression-guidance-managers

Cowling C (2008) A global overview of the changing roles of radiographers. Radiography, 14(suppl 1): e28-e32. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(08)00058-8/pdf

European Commission (2008) Explaining the European qualifications framework for lifelong learning. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from ec.europa.eu/ploteus/sites/eac-eqf/files/brochexp_en.pdf

European Federation of Radiographer Societies (2011a) EFRS definition of a radiographer. Utrecht: European Federation of Radiographer Societies. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from efrs.eu/publications/see/2011_EFRS_Definition_of_a_Radiographer?file=298

European Federation of Radiographer Societies (2015a) EFRS member societies survey. Utrecht: European Federation of Radiographer Societies. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from efrs.eu/publications/see/2015.05_EFRS_member_Societies_Survey_-print_version?file=324

European Federation of Radiographer Societies (2011b) Development of the radiographer’s role. Utrecht: European Federation of Radiographer Societies.[Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from efrs.eu/publications

European Federation of Radiographer Societies (2014) European Qualifications Framework (EQF) level 6 benchmarking document: radiographers. Utrecht, the Netherlands: European Federation of Radiographer Societies. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from efrs.eu/uploads/files/550d4d65-9c48-4841-83c0-1b2450ace4bd.eqf%20benchmarking%20document%20-%20radiographers_web.pdf

European Federation of Radiographer Societies (2012a) EFRS statement on radiographer role development. Utrecht:European Federation of Radiographer Societies. [Accessed:15 July 2016 2016] Available from efrs.eu/publications/see/2012_EFRS_Statement_on_Radiographer_Role_Development?file=300

European Federation of Radiographer Societies (2012b) EFRS statement on radiographer education in Europe. Utrecht: European Federation of Radiographer Societies. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from efrs.eu/publications/see/2012_EFRS_Statement_on_Radiographer_Education_in_Europe?file=299

European Higher Education Area (2005) The framework of qualifications for the European higher education area. Bergen: The European Higher Education Area. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from: http://www.ehea.info/article-details.aspx?ArticleId=67

European Society of Radiology (2009) Response of the European Society of Radiology to the European Commission green paper on the European workforce for health. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from alliance-for-mri.org/html/img/pool/ESR_Response_Green_Paper_EU_Health_Workforce_March_2009_Final.pdf

Furby CAW (1944) The future of the radiographer. Radiography,10: 9-10. Cited in: Bentley HB (2005) Short communication: early days of radiography. Radiography, 11: 45-50. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from infona.pl/resource/bwmeta1.element.elsevier-2222c3c2-dd17-3e1a-8f5a-296a421085af

Hardy M, Snaith B (2006) Role extension and role advancement –is there a difference? A discussion paper. Radiography, 12(4): 327-31. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(05)00143-4/abstract

Hardy M, Snaith B, Scally A (2013) The impact of immediate reporting on interpretive discrepancies and patient referral pathways within the emergency department: a randomised controlled trial. BJR, 86(1021): 20120112. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23255536 >

Henderson I, Mather S, McConnell J et al. (2016) Advanced and extended scope of practice of radiographers: the Scottish perspective. Radiography, 22(2): 185-93. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(15)00138-8/abstract

Judson E, Nightingale J (2009) An evaluation of radiographer performed and interpreted barium swallows and meals. Clin Radiol, 64(8): 807-14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19589420

Kelly J, Piper K, Nightingale J (2008) Factors influencing the development and implementation of advanced and consultant radiographer practice – a review of the literature. Radiography, 14: e71-8. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1078817408001090

Lockwood P (2016) An economic evaluation of introducing a skills mix approach to CT head reporting in clinical practice. Radiography, 22(2): 124-30. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(15)00116-9/abstract

Lockwood P, Piper K, Pittock L (2015) CT head reporting by radiographers: results of an accredited postgraduate programme. Radiography, 21(3):e85-9. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(14)00154-0/abstract

McNulty J, Rainford L, Bezzina P et al. (2016) A picture of radiography education across Europe. Radiography, 22(1): 5-11. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(15)00119-4/abstract

Moran S, Warren-Forward H (2016) The diagnostic accuracy of radiographers assessing screening mammograms: a systematic review. Radiography, 22(2): 137-46. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(15)00120-0/abstract

National Audit Office (2011) Managing high value capital equipment in the NHS in England. London: National Audit Office. [Accessed: 15 July 2016 2016] Available from nao.org.uk/report/managing-high-value-capital-equipment-in-the-nhs-in-england/

NHS England (2014) NHS Imaging and radiodiagnostic activity, 2013-14 release, 6th August 2014. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/diagnostics-waiting-times-and-activity/imaging-and-radiodiagnostics-annual-data/

Nightingale J, Hogg P (2003a) Clinical practice at an advanced level: an introduction. Radiography, 9(1): 77-83. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(03)00005-1/abstract

Nightingale J, Hogg P (2003b) The gastrointestinal advanced practitioner: an emerging role for the modern radiology service. Radiography, 9(2): 151-60. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(03)00038-5/abstract

Piper K, Buscall K, Thomas N (2010) MRI reporting by radiographers: findings of an accredited postgraduate programme. Radiography, 16(2): 136-42. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(09)00111-4/abstract

Piper K, Cox S, Paterson A et al. (2014) Chest reporting by radiographers: findings of an accredited postgraduate programme. Radiography, 20(2): 94-9. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(14)00004-2/abstract

Price R, Le Masurier S (2007) Longitudinal changes in extended roles in radiography: a new perspective. Radiography,13(1): 18-29. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1078817405001574

Reid K, Rout J, Brown V et al. (2016) Radiographer advanced practice in computed tomography coronary angiography: making it happen. Radiography, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2016.03.006. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(16)30002-5/abstract

Royal College of Radiologists (2015) Clinical radiology UK workforce census 2014 report. London: The Royal College of Radiologists. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from rcr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/bfcr153_census_20082015.pdf

Snaith B, Hardy M (2007) How to achieve advanced practitioner status: a discussion paper. Radiography, 13(2): 142-6. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(06)00002-2/abstract

Snaith B, Hardy M, Lewis EF (2015) Radiographer reporting in the UK: a longitudinal analysis. Radiography, 21(2): 119-23. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(14)00138-2/abstract

Society and College of Radiographers (2012) Scope of radiographer practice survey 2012. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from sor.org

Torres-Mejía G, Smith RA, Carranza-Flores M de la L et al. (2015) Radiographers supporting radiologists in the interpretation of screening mammography: a viable strategy to meet the shortage in the number of radiologists. BMC Cancer, 15: 410. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25975383

Woznitza N, Piper K, Burke S et al. (2014) Adult chest radiograph reporting by radiographers: preliminary data from an in-house audit programme. Radiography, 20(3): 223-9. [Accessed: 15 July 2016] Available from radiographyonline. com/article/S1078-8174(14)00016-9/abstract