HealthManagement, Volume 21 - Issue 3, 2021

An overview of the consequences of neglecting mental health and a case study of reorganisation of mental health service practices in Asti County, Italy.

Key Points

- Mental health as a strategy of care for targeting inequalities as direct determinants of diseases.

- Reorganisation of the practices of mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Asti, Italy.

- Involvement of local communities to face the new needs of the patients related to COVID-19.

Framework

The state-of-the art of the role and effective management of mental health assistance, in the context of a political and cultural scenario increasingly focused on the issues of strict economic sustainability, represents the specific object of the analyses, recommendations and proposals embedded in debates covered by the major scientific journals (not necessarily psychiatric) but dealing with issues of public health. The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development (Patel et al. 2018) represents one of the most significant contributions to the multiple controversial hot points, which can be seen as an apparently contradictory combination of two consensus.

The first consensus clearly states that mental health is a neglected area of medicine: nothing new or relevant has been produced since a long time in terms of new and effective treatments, of basic research related to biological determinants of diseases, and - more importantly - on reliable outcome measures corresponding to hard indicators of cost/effectiveness.

In this context of absence of new data, only ethically and politically correct recommendations indicate what should be done, but their outcome is limited, and the final consequence confirms the disinvestment and sociocultural marginalisation of psychiatry (Saraceno 2018).

The other consensus says that mental health is the challenging test for strategies of care that target the increasing inequalities which characterise and are direct determinants of those acute or chronic diseases (from evidence of the scientific literature of the last years) known to depend not only on biological-medical causes, but also from life conditions and contexts.

No doubt mental health is a comprehensive representative of these scenarios, and that only innovative, diffuse, long-term research could be a bridge between the two consensus with diffuse field experiments, in multiple contexts of practice and not simply through conceptual debates. Occasional studies are hardly representative or sufficient to produce the significant changes needed to deeply modify rooted paradigms of care (Tognoni 2020).

The Global Experimental Laboratory of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The emergency scenarios which invested as a true global tsunami the health services of all societies generated two-fold results. On one side, a heavy burden for the already ‘minimal’ mental health services, and on the other side the unexplored challenge of facing the new problems.

The rigid lockdown generated problems in the management of the patient populations already in charge of the services, along with the almost certain delayed emergence of relapsing as well as new ‘atypical’ cases. A chronicle from the real-world may be inferred from the events encountered in a Mental Health Service in the Northern Region of Piemonte, (Asti, Italy), that may be considered as paradigmatic for the best way of providing an informative picture on the practices and the outcomes to be documented over one year for the patients and the service.

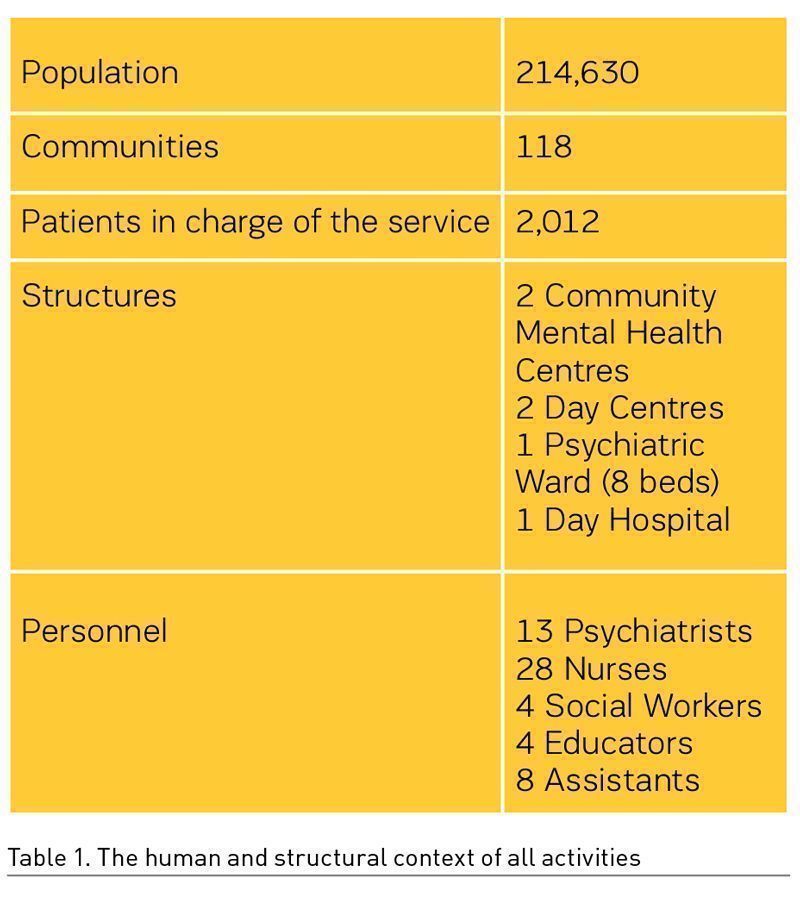

The Mental Health Service of the Asti County is placed in a rural context in the southern part of the Piemonte Region, characterised as a middle-income area with an environment marked by social tolerance and acceptance. Furthermore, the area has experienced projects of involvement of stakeholders in the evaluation and monitoring of the performance of the Mental Health Services (Corbascio 2010; Barbato 2014). More importantly, an association of family carers and patients is present and strongly operative in the area.

The initial phase of the pandemic emergency coincided with a complete lockdown and with suspension of all the activities in the country, essentially a shock for everyone and for the entire health system. Mental health services have been characterised by a generalised slowdown of their activities, giving answers only to urgent situations. This choice led to important limitations of access to services by most of the patients in charge. The closing of the day centres with the suspension of all the group activities forced most disabled persons to be confined at home, losing interpersonal contacts combined with significant difficulties in taking care of everyday needs.

The principal challenge for the professionals of mental health services was to maintain contact with the patients in charge, taking into account the compliance with the new rules of physical distancing. The first step included involvement and responsibilisation of the patients through an educational process aimed at providing basic rules for interacting with other individuals in a safe way. Actually, this resulted in a bi-directional process between professionals and patients based on an exchange of the reciprocal experiences in dealing with the new behaviours necessary to prevent and counteract the transmission of COVID-19. Out of the professionals, nurses undertook the actions of a learning process starting from a solidarity basis, relying upon the common sense that ‘nobody can save himself alone’. After this educational path, patients became easily aware of the surrounding pandemic situation, and were enabled to cope with the new situation. Again, an unexpected result was that the group of the patients gave to the professionals a civility lesson, immediately adhering to and applying the new rules imposed by the pandemic.

The second step necessary to meet patients’ needs has been the shift of the focus of service activities to home visits and encounters in uncommon places, such as public gardens, town squares, etc. (Coppo 2020). Surprisingly, there has been a significant reduction (50-70%) of psychiatric admissions to the psychiatric wards in the general hospitals, not explainable simply by the temporary closure of the wards due to unavailability of the staff (Gessen, 2020). Patients have been addressed to use other types of assistance, provided by the community mental health centres (Saponaro 2020). Besides new development of distance monitoring (such as phone calls and video calls), home visiting has been essential not only for assessment of the clinical conditions but also for evaluation of the living context and situation during the lockdown. A critical role has been the need to change day routines by the patients, helped in this task by the professionals that suggested new activities, even on a day-by-day basis, by phone calls and video contacts.

Involvement of the local community, i.e. the mayors, the parishes, the voluntary associations, the general practitioners, have all actively participated to the call for supporting the patients, also by reporting on difficult situations that needed the service action. In an indirect way and especially in small rural towns, the pandemic acted as a trigger of a new sense of the entire community, by generating participative and inclusive behaviours by most of the citizens, reducing in this way the stigma marking mental health patients. These positive experiences of social inclusion have indicated the need for vigorous interactions and integration among all actors on the social scene, in order to attempt a reduction of the social differences and inequalities massively induced by the pandemic. This task needs to be reached through local and national agreements designed to help public and private Institutions to work together guided by a common objective.

Lessons Learned During the Pandemic

First of all, mental health services must move to the patient’s living context in the most flexible and adaptable way, acting to melt together the different opportunities of curing and caring, activating all the resources available on the scene. This goal should be approached with creativity, not with simplified and pre-formed answers to problems. It is necessary to avoid fragmentation of the efforts of the services, by building alliances and sharing responsibilities to tackle the social problems evoked by the pandemic.

Secondly, the pandemic has exposed the dramatic effects of the institutionalisation of the aged and disabled populations causing the highest number of deaths. This point reminds us that every person must have an individualised care plan, realised in a normal life context with the possibility to exercise the right to choose, to decide what is best for their personal life. Nevertheless, it is an accepted point that the possibility to exercise personal rights is the basis for starting a therapeutic programme (Castelfranchi 1995), as the application of the Basaglia’s reform has fully demonstrated in the last forty years.

Looking Forward

Organisational creativity including personnel, managerial and administrative flexibility, proximity, confidence and sharing are the few keywords that witness what has factually happened in one year in the intense and often stressing environment of our ‘laboratory’. At the same time, it could be felt as a deep experience shared by the personnel and - more importantly - by the patients and their living context.

It is clear that the terms proposed above hardly comply with the definitions of disciplines with formal qualitative and quantitative vocation and objectives. However, these terms have emerged as a widely perceived narrative shared among all the stakeholders (patients and families, as individuals and groups). On the other side, it is not difficult to recognise in the same words a value-assessment background when they are confronted with their more formal synonyms: care, participation, empowerment, personalised interactions, contexts - and individual-targeted strategies.

The main and methodologically important difference between the two scenarios outlined above is clear: the first set of words correspond to a culture and resources available in a practice where risks, lives are shared, to collaboratively look to solutions.

The second set of words are expression of a ‘discipline’ aimed at assuring a functional system through the assessment from outside of the interventions, i.e. objects, and inevitably assign to the ‘subjects’ of needs the role of a dependent variable.

The ‘natural’ fall of the administratively rigid walls between the health and civilian areas of responsibilities represent the most remarkable indicator for a future, where the needs and the rights of those that are less autonomous are at stake. The translation of the obviousness of ‘non-obedience’ to the prescribed bureaucratic legal restraints in an emergency is certainly an important area of ‘civil research’.

On the same line, the other protagonists of the pandemic scenario in the mental health system, which require a creative follow-up, are the true determinants of the contexts, i.e. space and time. They are the true novelties, non-medical, certainly caring and cultural. The model proposed is that of a Mental Health Service endowed with an ever-changing ‘patient-centred’ agenda that moves where needs-rights-patients are, with no restrictions, without paying attention to measures of performance.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Barbato A, D’Avanzo B, Corbascio C et al. (2014) Involvement of Users and Relatives in Mental Health Service Evaluation. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202:479-486.

Castelfranchi C, Pirella A, Henry P (1995) L’Invenzione Collettiva. Edizioni Gruppo Abele, Torino.

Coppo A, Longo R, Cosola A et al. (2020) New strategies to promote citizens’ mental health in the times of COVID-19. Epidemiol Prev, 44:394-396.

Corbascio C. (2010) Rapporto 2007-2010, Centro Nazionale per la Prevenzione e il Controllo delle Controllo Malattie, Ministero della Salute, Italy.

Gessen M (2020) Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the Coronavirus? The New Yorker, April 21.

Patel V, Saxena S, Lundt C et al. (2018) The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Devolpment. Lancet, 392:1553-1598.

Saponaro A, Ferri M, Ventura C et al. (2020) Monitoraggio impatto pandemia COVID-19 sui Servizi di Salute Mentale e Dipendenze Patologiche. Sestante, 10:13-19.

Saraceno B (2018) Che cos’è oggi la psichiatria? Luci e ombre della Global Mental Health. Italian Journal of Social Policy, 2:21-34.

Tognoni G, Macchia A (2020) Health as a Human Right: A Fake News in a Post-modern World? Development, 10:1-7.