HealthManagement, Volume 4 - Issue 1, 2010

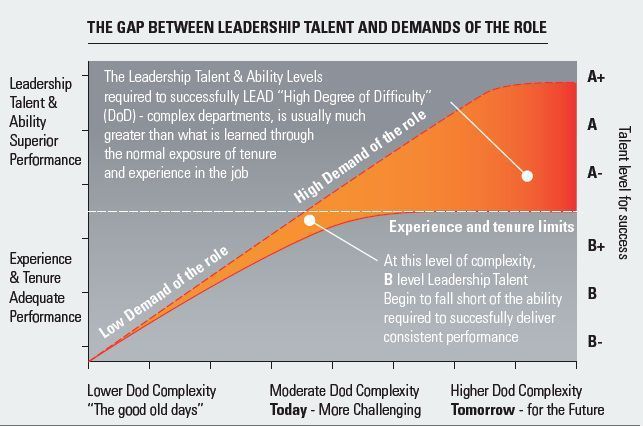

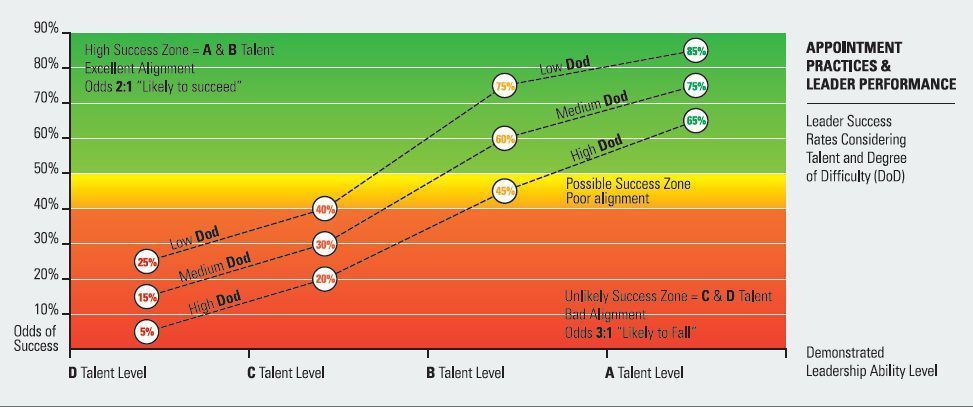

Programmed to under-perform? This is how some healthcare managers may feel when they go home after a typical day at work, according to a recent white paper ‘What Does Being in Over Your Head Look Like’. In reality, the average healthcare organisation creates leadership alignment (the right people in the right roles) approximately 55 percent of the time. Realistic expectations for leadership appointment should target 85 percent alignment, by using a structured approach to determining their future leaders. The difference of having the right leaders in place can show as much as a 75 percent increase in operational performance over time.

There are several common appointment mistakes that may lead to sub-optimal performance, where newly appointed healthcare leaders and managers whose talents are not best matched to a new role, can end up in over their heads.

The easiest way to describe the condition is where a department’s complexity (degree of difficulty) exceeds the threshold at which a manager has higher odds of success (typically above a 50 percent rate). There are different levels of ability. For a ‘C’ level ability, this is virtually any management job, since their chances of success are at best just 40 percent (in the lowest complexity positions). The decision to appoint a ‘C’ level manager to high positions is justified only when challenges are easily managed, or if the manager has an exceptional ability to manage day-to-day operations.

How about ‘B’ level managers? As cited by Thomas J. DeLong and Vineeta Vijayaraghavan in their 2003 ‘Harvard Business Review Article’, ‘Let’s hear it for B players’, managers at the ‘B’ level are solid, consistent performers. They are competent, experienced, consistent and loyal.

These managers make up the backbone of any organisation, and

typically account for between 50 percent and 55 percent of executives. In our

research, the bulk of healthcare IT managers are usually at the ‘B’ level. For

‘B’ level leadership talent, the ability to manage low and medium complexity

tasks produces favourable results, respectively, 75 percent and 60 percent of

the time (see Figure 1). The only cases with low odds of success (and are ‘in

over their heads’) is when they are appointed to complex assignments or

departments, accompanied by a high degree of difficulty. It is here that the chances

of success dip to 45 percent. This is not to say that they cannot be

successful; it is just less likely. If a decision is made to appoint ‘B’ level

IT managers to such a level of complexity, it is crucial for CIOs to ensure

that they ‘over achievers.

Other attributes of “B” level leaders are:

- They are talented but not usually as ambitious or driven;

- They are interested in advancement but not at all costs or a steep price;

- They define success differently (not purely financially or status motivated);

- While they may work hard, they prioritise “life-work” balance to work 50 hours per week instead of 80 or more;

- They are usually excellent team players avoiding the spotlight of self promotion;

- They may have been “A” level performers at one time and have dialled back their career focus due to outside – personal priorities or possibly “throttling” down to semi-retirement;

- They have longer tenures in organisations because they are less likely to leap from job to job to fast track or advance their careers, or

- They contain a significant amount of an organisation’s intellectual capital due to their experience and tenure levelling.

In such a light, there are seven typical appointment mistakes which organisations make:

- Appointing a “B” level ability person to a high degree of difficulty management role based upon their tenure period or technical competency (clinicalexpertise); the ability to lead othersdoes not correlate with either. Oddsof success = 45 percent.

- Appointing a lower level “supervisor” into a manager position in a bottom quartile

department out of convenience. They are usually unsuccessful because of their

lack of manager experience. They tend to be part of the previous culture and

are less likely to act on the low performers (or make tough decisions). Odds of

success = < 20 percent.

- Failure to recognise that a high degree of difficulty department in the bottom quartile will require a ‘turnaround’ specialist used to making tough decisions quickly, with responsibility to stakeholders outweighing personal interests. Most ‘B’ level managers do well in maintenance roles. Odds of success = < 20 percent.

- Waiting too long to act and failing to set hard (measurable) performance targets and milestones for the first year. If new managers fail to immediately make heavy-lifting decisions (especially in terms of dealing with negative, disruptive, poor performers), turnarounds take longer, are usually more painful and have a lower overall success rate. Odds of success = < 20 percent.

- Not taking due account of leadership talent or ability. Assigning a ‘C’ or ‘D’ level leader in any role has low odds of success: average 30 percent for a ‘C’ player and 15 percent for a ‘D’.

- Low acceptance rate of a new leader/manager by the staff because of an ‘old school’ mindset about the importance of prior tenure in a particular department. It can be extremely difficult for some people to handle this situation long enough to persevere. Odds of success = < 33 percent.

- Competency Alignment: Sometimes, even the most talented leaders (‘A’ players) can be out of alignment technically, with regard to business models, culturally/behaviourally or in terms of pure maturity or experience. Odds of success = < 33 percent.

Numerous

consultants promote the hiring of only ‘A’ players to leadership and/or total employee

positions. If less than .01 percent of healthcare organisations can achieve this

level of human capital recruitment, hiring and appointment, how realistic is it

as an aspiration? The last organisation that tried to create a culture of all

‘A’ players was Enron.

Another name for this business practice is ‘Top Grading’, where selection only screens for the best talents, while the performance management practices cut a percentage of the total employment base (GE is famous for cutting 10 percent of its bottom performers every year).

Such

a philosophy will simply not work at healthcare organisations. In the final analysis,

the healthcare business, like others, is a team sport.

Tom Olivo is CEO of Healthcare Performance Solutions, U.S.

[email protected]