The key to caring for the whole patient.

Person and family engagement (PFE) has been called the blockbuster drug of the 21st century. How can hospitals implement engagement so that patients and families are partners in patient safety?

What if I told you there is a new medicine that could accelerate medical error prevention, improve outcomes, reduce readmissions and increase your patient satisfaction scores? Would you be interested?

Now, what if I told you that this new medicine was also low-cost and tied to incredible success rates? Without a doubt, most hospitals—and most of your patients—would be interested.

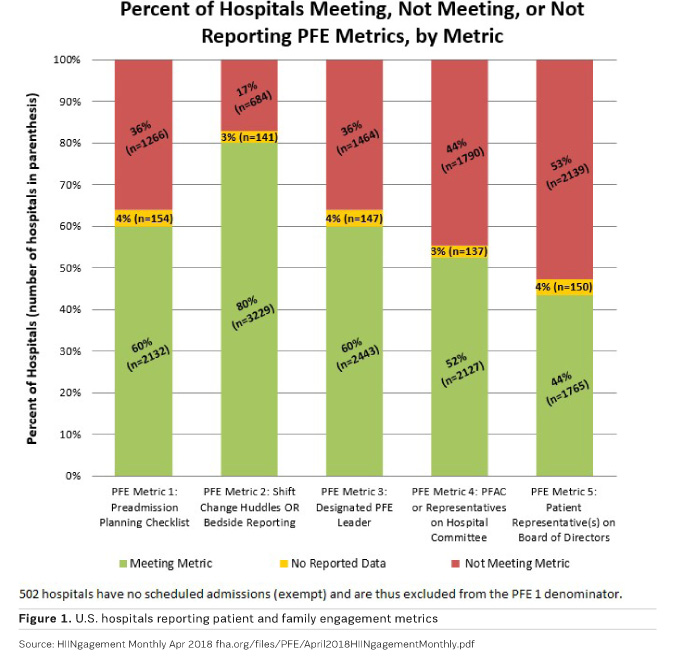

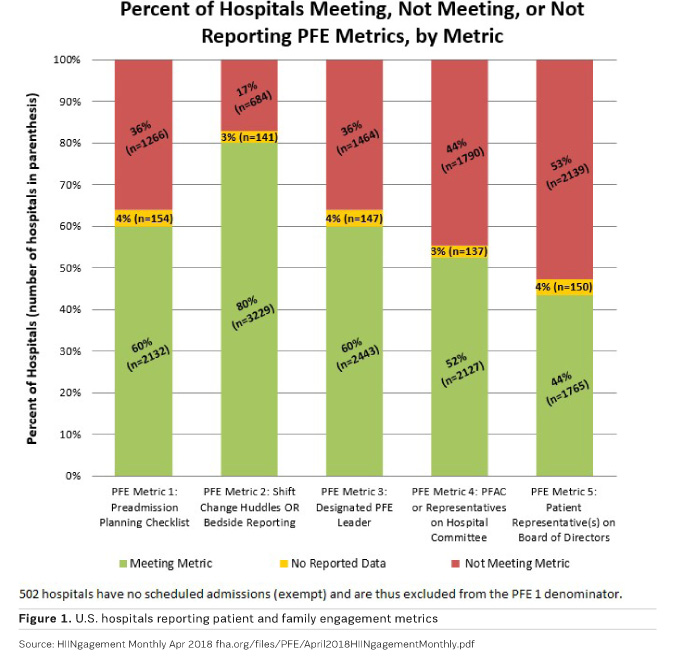

That low-cost, low-tech method to reduce medical errors is called person & family engagement (PFE), something Health Affairs editor Susan Dentzer calls the “blockbuster drug of the 21st Century” (Dentzer 2013). PFE has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as integral to its patient safety programme since 2005 (WHO 2006). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have embraced PFE as a transformation strategy and are now tracking implementation in every U.S. hospital (Figure 1).

Person and family engagement at its core is activating patients and their families as true partners in the planning, delivery and evaluation of patient care (Glover 2017). While it sounds simple, it’s a paradigm shift. PFE goes beyond informed consent in legal boilerplate language that few understand to real shared decision-making between patients and their providers. It is about open and honest communication and support for patient management in ways that involve family and community as part of the solution. It is about building a care relationship that is based on trust and inclusion of individual values and beliefs (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2017). It is also about healthcare providers continuously learning from the experiences of their patients.

Need for person and family engagement

Although patient safety has been seen as a healthcare priority for decades, an estimated 4.8 million people across the globe and over 200,000 people in the United States die in hospitals every year from preventable and avoidable causes (Makary and Daniel 2016). That makes medical errors the third leading cause of death in the United States and the fourteenth worldwide. Medical errors claim the lives of more people than HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, combined. For the first time 2018 research shows that more people die from poor quality healthcare worldwide than from lack of access to healthcare (Kruk et al. 2018). Everyone needs to engage to address this global crisis.

Death is not the only measure. Patient harm and the cost of care are both alarming. One in twenty outpatients experiences a diagnostic error, and an estimated 160 million medication errors occur each year in primary care each year (Singh et al. 2017). One in nine emergency room admissions is tied to medication error (AHRQ 2018).

The statistics don’t end there. The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) estimates that up to 80 percent of information shared in a primary care visit is immediately forgotten by patients (Kessels 2003). A recent study found that only 12 percent of U.S. adults had proficient health literacy, the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2007). And over a third of U.S. adults, about 77 million people, have difficulty with common health tasks, such as following directions on a prescription drug label (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008). Given the complexity of the healthcare system, it is not surprising that limited health literacy is associated with poor health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2007). PFE involves providers partnering with families and communities to support patients and populations who face these challenges.

Evidence to support person and family engagement

The evidence is accumulating fast. A study posted in the North Carolina Medical Journal found that patients who are actively involved in their health and healthcare tend to have better outcomes and care experiences and, in some cases, lower costs. Implementing patient and family engagement strategies led to fewer healthcare-associated infections, reduced medical errors, reduced serious safety events and increased patient satisfaction scores (North Carolina Medical Journal 2015).

Another study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that when patients and healthcare providers were primed for a conversation about a patient’s treatment plan, the chance that a goals-of-care conversation occurred was higher (Curtis et al. 2018). The study followed 132 physicians and 537 patients between 2012 and 2016. During this time, patients specifically primed for a conversation with their healthcare provider reported a significant increase in patient-reported goals-of-care conversations during routine outpatient clinic visits. Seventy-four percent of the intervention group reported having the goals-of-care conversation compared to only 31 percent of the usual care group.

The study noted that physicians caring for patients with a serious illness experienced more effective treatment, better quality of life, and reduced intensity of care at the end of life when fostering improved patient engagement (Curtis et al. 2018). Despite this information, physicians frequently do not have conversations with their patients about their prognosis and goals of care.

How do you implement person & family engagement?

Person and family engagement can be implemented in different ways. According to the CMS Quality Strategy (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services 2016), a PFE programme includes four goals:

- Actively encourage person and family engagement along the continuum of care within the broader context of health and wellbeing and in the communities in which they live. This will exceed the traditional boundaries of setting-specific care and will identify opportunities to bridge and forge partnerships among providers, persons and community resources.

- Promote tools and strategies that reflect person and/or family values and preferences and enable them to actively engage in directing and self-managing their care.

- Create an environment where persons and their families work in partnership with their healthcare providers to develop their health and wellness goals informed by sound evidence and aligned with their values and preferences.

- Improve experience and outcomes of care for persons, caregivers, and families by developing criteria for identifying person and family engagement best practices and techniques in the field from CMS programmes, measurements, models and initiatives, that are most ready for widespread scaling and integration across the country.

Under CMS’ strategy, they drive five main items which formed the basis for the actionable patient safety solutions (APSS patientsafetymovement.org/actionable-solutions/actionable-patient-safety-solutions-apss) on person and family engagement. The five pillars include:

- Implementation of a discharge checklist—this ensures that all patients are getting the same level of care systemwide regardless of how busy a unit may be. Included in this checklist is information including where are you going, do you have a caregiver at home, do you have a way to get your medication, etc.

- Bedside huddles or shift changes at the bedside—where you engage the patient rather than talking about or over them.

- Staff—Are there people in your organisation who coordinate PFE?

- Start a Patient Family Advisory Council— this brings in the wisdom of the patient who has experienced hospital care into improvement work.

- Do you have someone who identifies primarily as a patient or family caregiver on your Board of Directors?

Implementation of CMS’ strategies have proven to yield positive results

At Parrish Medical Center (Titusville, Florida), they’ve utilised the Patient Safety Movement’s PFE APSS and CMS’ person and family engagement strategies to improve handoff communications (HOC). The hospital used the checklists in the Patient Safety Movement APSS and built a process around it. The goal of the new handoff process was twofold:

Zero harm in transitions from the medical-surgical unit to the emergency department

Implement person to person handover, including the person in the bed.

The hospital also used their electronic medical record as a means to help capture transitions in care and instructions.

“We had experienced a number of patient harm events related to HOC and wanted to find a measurable way to improve. In designing this new process, we created a checklist, utilised the electronic medical record and decided that we wanted all transitions in care to be person to person. We felt it was important to include the person at the centre of this care, namely the patient, as well as the nurses,” explains Parrish Medical Center’s Chief Nursing Officer Edwin Loftin.

The process was implemented 6 May 2018, and in just four weeks demonstrated remarkable results.

Before the change, Parrish Medical Center recorded 48 events of patient harm in 1.5 years, whether that was medication error, delay in care, etc. Since the implementation of the new handoff process, the hospital has had zero harm events in 600 transitions.

The new handoff process has had additional benefits, including a 35% decrease in time of transition, whether that is transitioning a room or implementing care as well as increased patient satisfaction.

The hospital plans to release final results of their implementation in 2018. But what about your hospital? It is time to engage patients and families as partners to improve patient safety.

Key Points

- Patient and family engagement enables partnership in planning, delivery and evaluation of patient care

- PFE is low-cost and low-tech and has the potential to reduce medical errors and improve patient safety

- Parrish Medical Center has implemented a new handoff process, with positive results