HealthManagement, Volume 20 - Issue 6, 2020

Key Points

- Staffing and working conditions are the driving factors for achieving a high-quality level of care.

- Economic success directly correlates with a corporate culture that entrenches customer orientation, uncompromising quality and purpose for the employees in the corporate value system.

- Quality in medicine and patient experience result from employee satisfaction, which is a consequence of working conditions.

- Magnet Nursing managers lead through listening, questioning and feedback.

- Actions and behaviours shape attitudes and beliefs rather than vice versa.

The care staff constitutes the largest occupational personnel group at hospitals and care institutions. This group has the most time-intensive and closest contact with patients. Nonetheless, as a result of cost pressure, many hospital managers tend to conduct short-term cost savings through work intensification (the combining of jobs) or even reduction of the care personnel number, instead of using care standards as a basis for problem-solving.

Context

Hospitals are service enterprises, in which medical services for people (patients) are provided, who generally find themselves in a borderline situation, both physically and psychologically (fear, pain, loss of autonomy). Professionalism, knowledge and empathy on the part of the care personnel largely determine the quality of patient care.

Given the complexity of medical care services (disease-specific, individual patient provision with diagnostic, therapeutic, care and other services), quality requirements in terms of the ‘confidence good of medical service’ can only be ensured through outstanding communication and cooperation, which is interdisciplinary and intergroup (in the sense of different professional groups).

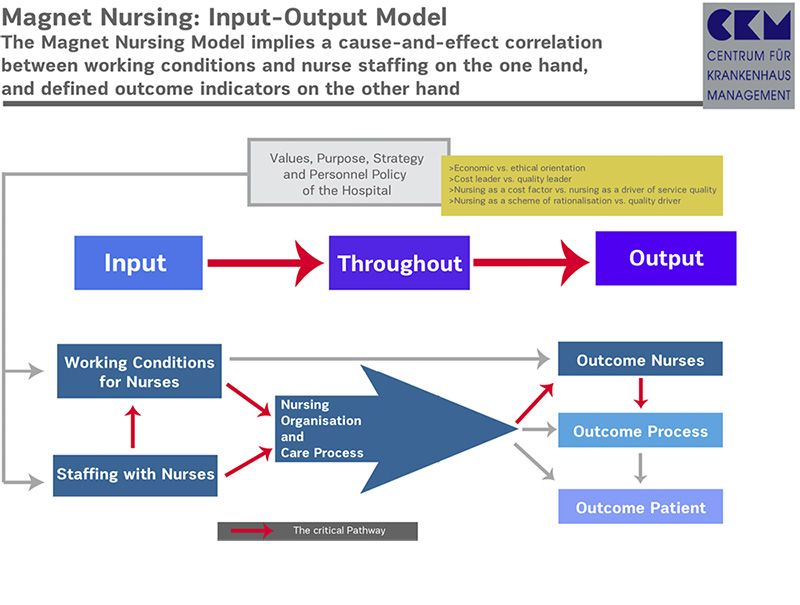

There is a direct interrelationship between the organisation of work processes, the motivation and professionalism of employees, medical quality as well as patient satisfaction (Figure 1).

The daily reality in hospitals, by contrast, is all too often characterised by work intensification, time pressure, error-prone work processes, employee demotivation and patient dissatisfaction.

In addition to organisational deficiencies, deficits through work-reducing equipment and insufficiently effective professional and interdisciplinary cooperation, there are also communication deficits and gradual rationalisation, which lead to burnout syndrome and declining willingness to perform.

Against the background of imminent deficit of qualified care personnel and doctors, and in parallel to the increased demand for medical care performances, the question arises as to the extent can the Magnet Nursing Concept contribute to overcome this dilemma.

Criteria of Magnet-Hospital: ‘Magnet Forces’

The American approach to magnet hospitals is originally based on medical institutions, in which care personnel with excellent subject-related competence contribute to providing outstanding medical services (ANCC 2020; Summers 2020). As such, the patient care process proceeds smoothly and with low risk, innovations are implemented in a timely and effective manner, and patient satisfaction is high (McHugh 2013). Magnet Hospitals direct the care activities in an evidence-based manner, that is subject to an orientation towards care-sensitive performance indicators.

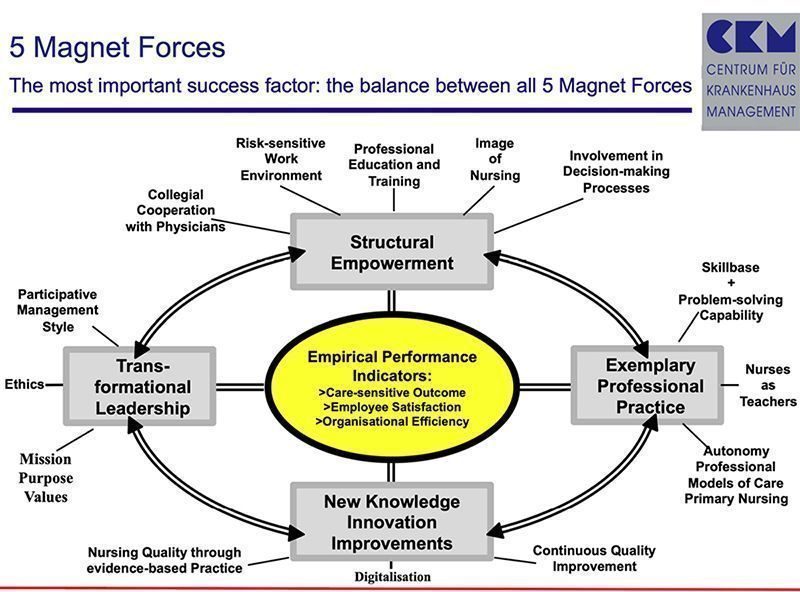

In addition, work satisfaction is high and the fluctuation rate is low. The employer attractiveness of a Magnet Hospital results from the orchestrated implementation of the ‘14 forces of magnetism’ and the ‘8 principles of action,’ which serve as an organisational culture guideline (Peters and Waterman 1982). These criteria are summarised as the model of the ‘5 Magnet Forces’ (Figure 2).

‘Forces of Magnetism’

The ‘14 Forces of Magnetism’ are the foundation of excellent care services. They aim at establishing participative management, an organisational structure oriented towards delegation and characterised by constructive interaction and transparency, as well as an environment that is safe and promotes healing.

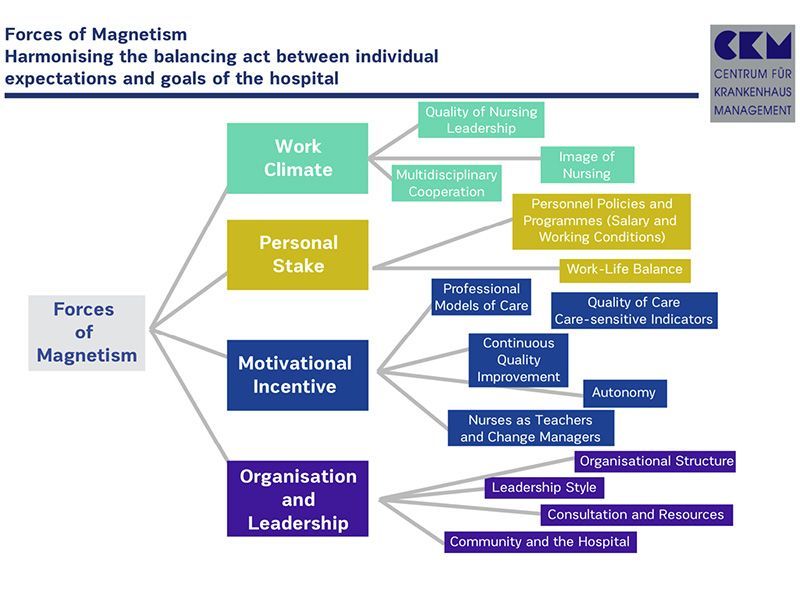

Individual goals and personal interests of the employees are harmonised with the medical requirements, as well as the business-related imperatives of the hospital business (Figure 3).

Leadership quality of nursing managers

A nursing manager (NM) is competent in terms of skills, professional experience, effective implementation, and is extremely risk-aware with regard to the patients. Through actively setting an example, providing the necessary resources and practicing a participative leadership style, the process ensures that the daily guiding principles of care are used to the full benefit of the patients. An NM initiates programmes for improving patient safety, optimising work processes and organisational structures as well as ensuring infection prophylaxis. An NM leads by listening, questioning and giving feedback.

Organisational structure

Flat hierarchies at the ward level and systematic involvement of care personnel in decision-making processes and project groups ensures sound decision-making, which can be implemented rapidly. An NM is a member of the hospital management and reports to the CEO on a regular basis, as well as to the supervisory board. For medical departments, care area leaders are established, who work together with the department head doctors organising patient care.

Leadership style

The leaders practice an employee-oriented management style. Reciprocal, inter-hierarchy feedback, agreement on quality objectives, open error management, and suggested improvements are welcome, and participation in decision-making committees is expected. Leaders are accessible to employees (‘Open Door Leadership Policy’). The communication culture is open and results-oriented. Decisions are made in interdisciplinary teams, also involving patients and their relatives (informed consent).

Personnel policy and programmes

Employees receive competitive salaries that are appropriate in terms of the particular responsibility that they carry. There are also individual performance and success-oriented additional payments based on commitment, collegiality and undertaking project activities for quality improvement – but there is no orientation towards economic goals. Employees have a right to participate in making decisions on work processes, working hours and career perspectives. Shift rotations are regulated in a health-promoting and family-friendly manner. The integration of family and work is an important objective of work formulation. There are transparent possibilities for development in both specialist and management careers. Rotations in new subject areas (e.g. purchasing or medical controlling) enhance the learning potential and knowledge of the entire organisation.

Professional care models

Care models provide care personnel with a consistent overall responsibility for individual patient care, assign them with clear task areas, and equip them with necessary authority (decision-making, resources). For coordination and implementation of all care measures, there is also organisation-wide, entrepreneurial handling of resources (i.e. willingness to innovate and cost awareness). The care model of choice is that of ‘Primary Nursing.’

Care quality

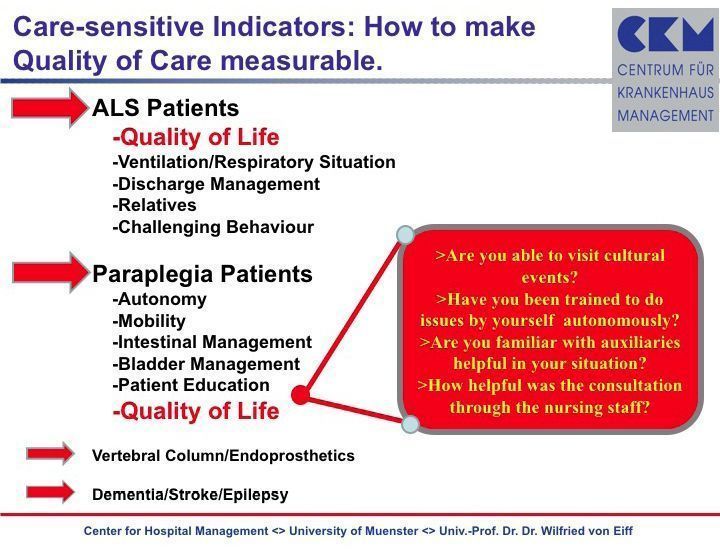

Care quality is oriented towards the ‘Patient first’ principle. Accordingly, the leading care personnel are responsible for creating structural conditions, which promote high quality. This applies to the provision of equipment for work simplification (patient lifts, electric beds, mechanical aids for standing up), patient risk reduction (e.g. electronic provision cabinets for avoiding medication errors), and hygiene maintenance (self-cleaning toilet facilities). Care quality is provided on the basis of measurable care-sensitive indicators and the consistent application of Lean Management instruments (e.g. Liker 2004) with the aim of continuous improvement. These care-sensitive ratios are a precondition for autonomous planning and delivering of care (Figure 4).

Continuous quality improvement

Care personnel are familiar with the modes of thinking (Kaizen), the methods (PDCA-cycle) and techniques (e.g. Ishikawa-Diagram) of Lean Management, and each employee is expected to apply this knowledge with initiative and continuously, to ensure that process improvements not only benefit patients but also lead to more effective work design.

Autonomy

Care personnel work independently on the basis of care standards. They themselves recognise care requirements and can determine which measures should be introduced. Autonomy is also achieved through the delegation of tasks, expertise, or authority and responsibility. The provision of care is constantly evaluated through care-sensitive indicators, and based on this, measures are undertaken for continuous improvement.

Care personnel in various roles

Care personnel are involved as trainers in various educational programmes, both internal and external to a particular hospital. They also participate in and are responsible for scientific projects for examining clinical evidence, alternative forms of patient care, wound management, and so on. Care personnel independently initiate projects for improvement and are responsible for the implementation of innovations within the ward processes and procedures.

Image of care personnel

The work of care personnel is regarded as a substantial success factor within the context of work groups in hospitals, and is associated with a high level of recognition and communication in personal interactions. The hospital management ensures that the care profession is also regarded by the public as valuable, demanding and challenging.

Interdisciplinary cooperation

Goal-oriented, smoothly functioning interdisciplinary cooperation and intergroup work is the basic condition for the complex medical care of a patient in a hospital. It should be conducted in a medically appropriate, ethically oriented manner, with minimal patient risk and the integration of the best possible expert skills as well as economic viability. Mutual respect of the various professional groups is necessary and promoted through a targeted cooperative work programme. Therapy decisions are made according to the principle of ‘Shared Decision-Making.’

Professional human resources development

The organisation consistently places value on formal qualifications, continuous certified training and career planning, allowing for switches between medical-related and management careers. Professionalisation and specialisation are promoted to foster effective delegation, and through the division of work, to achieve the best possible value and benefit for patients, while at the same time, keeping costs under control. In this manner, specialised functions (e.g. wound management, pain management, triage nursing) and new occupational profiles (e.g. Physician Assistant) contribute to and justify the demands on carers for ongoing qualification and reduce the burden on doctors (e.g. Endo Nurse, Stroke Nurse), also through the increasing transfer of doctors’ activities to specifically trained personnel (e.g. Nurse Physician).

Anchoring within community/region

Magnet hospitals see themselves as an integral component of the community, and support its infrastructural and societal development. There are also programmes to counter youth unemployment, campaigns for safety in one’s leisure time, and second opinion procedures for practicing doctors. Furthermore, care personnel assume important coordination activities in the context of discharge management, as well as in the aftercare of special patient groups in need of assistance (ALS, paraplegic, stroke and dementia patients), through networking of various service providers (meals-on-wheels, family doctor/specialist doctor, social services, local support services, healthcare supply store, care services) directly after discharge.

Advice and resources

After their hospital stay, patients are also given specialised subject-related advice and supported organisationally. The discharge and transition management are of considerable value. Care experts are available at the hospital at any time for all areas of activity and departments. In future, advice around care services will be provided based on digital applications and wearables (home health services).

Insights and Conclusions

The approach of the Magnet Recognition Programme can act as an idea generator for European hospitals. This is particularly the case in view of an imminent shortage of qualified care personnel in nearly all developed healthcare systems.

The Magnet Initiative reveals a connection between work conditions (work time, equipment with resources, organisation) and incentive systems (payment, recognition), on the one hand, as well as patient satisfaction and medical quality, on the other hand. There is, in fact, a very clear interrelationship between employee satisfaction and patient satisfaction. The organisational-cultural setting (image and acceptance of professionals and trades, level of autonomy, cooperation) is the most important success factor along the path to the Magnet Status, that is towards an employee and patient-oriented work environment. The Magnet Status is a decisive factor for promoting success in achieving a brand status – in addition to the appropriate level of medical quality. It is necessary to have a modified understanding of rationalisation. It is not merely about reducing costs, but about reducing unnecessary activities that do not really benefit patients (Kenney 2010).

The concept is based on the conviction that organisational and personnel-related conditions for appointing employees must be characterised by the integration of ethical values (e.g. patient risks, error management).

Interdisciplinary forms of cooperative work promote appropriate medical results and enable learning processes for all participants.

In addition, it is necessary to draw attention to the fact that projecting an MN initiative onto a hospital means to start on a long journey of organisational and cultural change. Furthermore, significant investments in equipment, workflow optimisation, professionalisation of staff and behavioural training are a necessary precondition.

It is fair to say that an MN change management process will last at least seven years and requires investments at a minimum level of 2.5 million euro out-of-pocket money (Duquesne University n.d.) besides additional working hours needed for running continuous improvement circles.

References:

ANCC American Nurses Credentialing Center (2020) Magnet Model – Creating a Magnet Culture. Available from iii.hm/14h2

Duquesne University (n.d) What is a Magnet Hospital? Available from iii.hm/14h3

Kenney C (2010) Transforming Health Care. Virginia Mason Medical Center´s Pursuit of the Perfect Patient Experience. New York: Productivity Press.

Liker JK (2004) The Toyota Way. 14 Management Principles from the World´s Greatest Manufacturer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McHugh MD et al. (2013) Lower mortality in magnet hospitals. Med Care, 51(5):382-8.

Peters TJ, Waterman Jr. RH (1982) In Search of Excellence. Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies. New York: Harper & Row.

Summers S (2020) Changing how the world thinks about nursing. Coalition for better understanding of nursing. Available from iii.hm/14h4