HealthManagement, Volume 21 - Issue 2, 2021

Key Points

- From an organisational perspective, systematic competence management is an important part of any organisational change. Creation of balanced work environment based on thorough assessments and analyses is a key element.

- The staff perspective on competence management is affected by their time in the profession. New and experienced nurses require different approaches.

- When it comes to patients, their perception is completely different from that of the personnel and organisation. This is especially true for culturally different patients.

- Transitioning to value-based healthcare is more complex than in other sectors, in particularly because of the standardisation challenges.

- Combining standardisation benefits with the subject matter experts’ insight would allow for more efficient implementation of competence management strategies.

Competence Management: Organisational Perspective

On the meta-level, organisations often use the Healthcare Quality Competency Framework (Framework Wheel) with its 8 dimensions and 29 competency statements and 486 skills (NAHQ Framework Wheel) when it comes to the topic of competence in the organisation. This tries to encompass all aspects of quality offensives in the healthcare sector.

In this article we will primarily pursue the aspects of competence management in connection with personnel and leadership, with the aim of ensuring effective and efficient provision of service, improving employee satisfaction and minimising burnout.

Importance of competence management in change processes

Systematic competence management is particularly necessary for successfully coping with change processes. It does not matter whether it is about the introduction of new production processes, new software or IT solutions, or the introduction of management systems such as quality management systems.

Often the different competencies of the employees are not considered in a differentiated manner and the employees are trained according to the ‘watering can principle’ as part of the change process. In this way, knowledge is formally imparted, but without addressing individual needs to develop competencies. This leads to frustration for almost everyone involved. Despite the training, employees may still be overwhelmed by the upcoming changes. The management is dissatisfied with the performance of the employees and the results of the change process and, ultimately, employee resources have been used unsuccessfully.

Many change processes simply fail because of rejection by the employees. This rejection often develops from excessive demands on employees or a lack of integration into the change process. Burnout and high fluctuation can be the result.

At an early stage in the context of change processes, it is necessary to define the requirement and competence profiles for the individual work areas and the different role profiles. This ensures that employees are prepared in time, with the necessary skills for the new challenges.

Occupational health and safety as part of managerial responsibility

Occupational safety and health protection form the basis for implementing competence management and living it in real life. In combination with stable values, this creates a model that combines operational behaviour with strategic impact and corporate success.

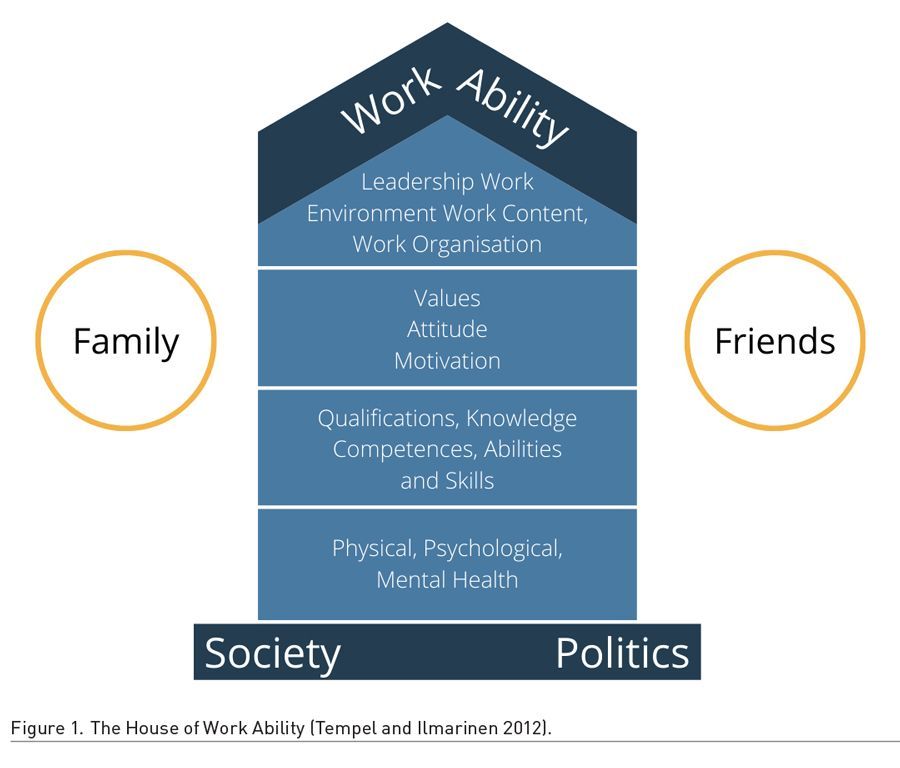

The House of Work Ability

It is the responsibility of employers to design work requirements (possibly stresses) in such a way that, as operational resources, they contribute to the fact that employees can and want to perform their tasks well without major risk. ‘Work (coping) ability’ describes the extent to which employees can perform their work considering the work requirements, health, mental resources, qualifications, values and attitudes. Ability to work is the correspondence between what a company demands in the long term and what a person can and wants to achieve. The factors that influence this correspondence are explained in the ‘House of Work Ability’ model (Tempel and Ilmarinen 2012) (Figure 1).

Reduced working capacity means reduced performance and productivity at the company level and human suffering for the person concerned.

Occupational safety and risk assessment

The institution, and consequently the management level, has a statutory duty of care towards its employees. In addition to the necessary safety measures, this includes the liability for objects and the maintenance of workplaces as well as resolving conflicts and observing the rights of employees. The European Framework Directive on Health and Safety at Work (passed in 1989) obliges all employers to carry out risk assessments, which (since 2013) have also included psychological stresses. Suitable tools and assistance are available in several languages via EU-OSHA.

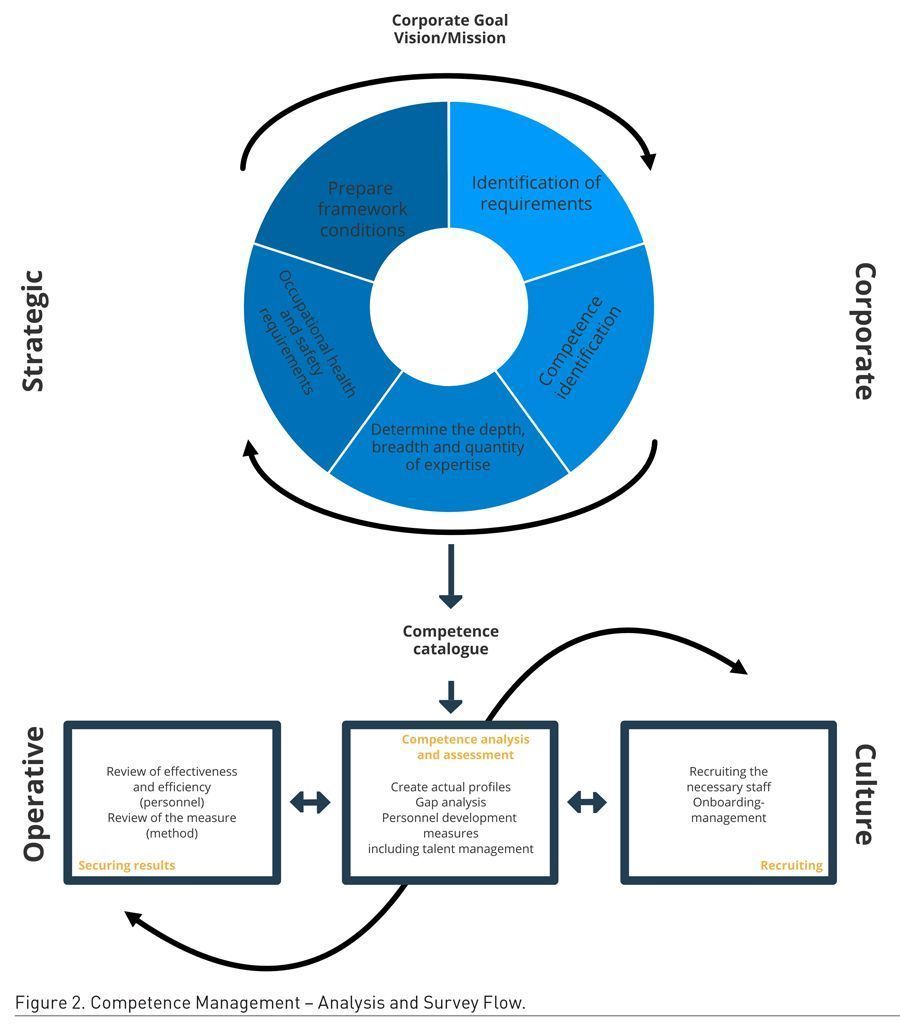

Competence management analysis and competence survey

The starting point, competence management is the actual competence of the employees, the so-called actual competence mix. Only those who know their foundations can build on them.

The second step is to determine the target state – also known as the target competence mix. This includes all employee skills that will be important for the company in the future.

Particular attention must be paid to the areas of the company that enable and create value and the skills required thereto.

The target/actual deviation indicates the personnel development requirements that need to be managed with a systematic approach. This can be achieved by way of personnel development of existing employees and/or additional new employees.

Another important step: competence perspective

In addition to the target/actual situation, the company perspective must also be considered. First, the different competence dimensions (technical competence, methodological competence, and personal and management competence) are analysed. In addition to this, it is also important to determine the breadth and penetration depth of the respective areas of competence dimension. The fourth aspect is the level of competence. This describes the theoretical and practical experience of exercising competence. This then results in a competency map of the company with the potential of a competency planning map.

Such competence analysis and survey enable, in addition to talent management and personnel retention, timely succession planning and supports the future of the company. For this purpose, however, employee skills and needs must be maintained and kept up-to-date. Due to the quantity and complexity requirements, only a digital solution is seriously recommended. This software should in turn be compatible with other HR software tools to avoid duplication, increased error problems and waste of resources due to multiple entries.

Implementation of competence management

To set up competence management successfully and efficiently, close coordination between management, HR and employees is necessary. For the necessary acceptance by the employees, it makes sense to always involve the employees in the development of the competence management. Since the initial effort can be very extensive, it is essential that the management actively supports the project and provides the necessary resources. The larger the number of employees in a company, the more complex it becomes to manage the skills of the employees. Systems that are based on process slips and spreadsheets quickly reach their limits and develop into a confusing bureaucracy. This is inefficient, costs money and has a demotivating effect on the employees involved.

Concentration on essentials and emphasis on core issues constitute decisive elements of a modern competence management. In the past, competence models were often designed with a great love to detail and extensive with as many business aspects and functions as possible. In the future, it makes sense to focus and, above all, to take account of the time that it takes to modify competency models to correspond to current needs. The solution lies in the mapping of roles in which less explicit requirements are defined, but above all strengths, potentials and necessary meta-skills are the basis. A dynamic adjustment of competencies is vital for many companies, especially in relation to the rapidly changing requirements.

Competence Management: Staff Perspective

The staff perspective of competency changes depending on the amount of time in the profession. New nurses will need a variety of competencies to show that they can be safe on a unit by themselves. These competencies should be worked on during an internship with their preceptor. Ideally, the preceptor should meet with the new nurse weekly to go over the competencies that have been completed, to discuss how well the nurse has done with these and what could have been done better. The nurse also needs to be told what competencies are left to be completed and about the plan for the week. The preceptor should also meet with the nurse manager to update them on the new nurse’s progress and status in the competencies. The problem with this from the staff perspective is that it is very time-consuming to complete the information that accompanies the number of competencies for a new nurse. In the U.S. some of this burden has been lifted by sending the new nurses to a simulation lab to complete their competencies.

Competencies for a more seasoned nurse should be tailored to the needs of the nurse or the unit. The bedside nurses should be involved in this so they have a say in what their competencies for the year will be. When they are involved, there will be better compliance with competencies, increased education, and decreased procrastination.

Competence: Patient Perspective

Patients view competence much differently than healthcare personnel. Their views are that the person is competent and empathetic, in other words, if the person taking care of me knows what they are doing and whether they are spending enough time with me and being kind. This is especially true with culturally different patients ranging from people who do not speak the local language, elderly, to the LGBTQ community. These populations will be especially critical of the staff competency and the facility. These competencies for the patients are interpreted to soft skills such as communication and patient-centred care. These competences will translate into a change in the HCAHPS scores in the U.S., or patient satisfaction scores (Howe et al. 2019).

Healthcare as Value Chains

Healthcare systems as any other enterprises are production systems. Using input factors are transformed into output through a value chain, very much in line with the theories established by Michael Porter and later refined and applied to the healthcare context (2006). The explanation of healthcare systems as value chains has increased in recent years with the result of high numbers of lean production initiatives, aiming to maximise customer value and minimise waste (Poksinska 2010).

Traditionally production goals have been efficiency measured quantitatively, in terms of cost per unit, or, in the healthcare context, as price per procedure completed. In recent years, there has been more focus on the effects of treatments. Different measures and methodology have been put in place to understand and quantify increased quality of life for patients, which is a significantly more complex concept than counting completed knee surgeries according to specific procedure. The trend is captured in the concept of value-based healthcare (discussed in our first article) with a higher focus on curve data, which monitors the posttreatment aftermath for a patient.

Standardisation Dilemma

Patient satisfaction and their well-being during the treatment have raised on both the political and the providers agenda over the last decade. ‘Patient journey’ provided in collaboration (or despite lack of collaboration) between different actors and stages in the holistic treatment journey, such as transfer from primary healthcare to speciality healthcare, and community. Countries with a high degree of uniform national healthcare systems, such as many European countries, have been implementing healthcare reforms in order to standardise healthcare within an end-to-end perspective as fully integrated value chains. Countries with a high degree of private and independent healthcare systems have experienced large consolidations of providers, aiming for optimisation through standardisation. Standardisation is one of the oldest tools in the toolbox for business process optimisation, and served as key to quality and profitability improvement throughout industrialisation and post-industrialism, from the theories by Taylor (1911) all the way to Toyota, IKEA and Apple, public services and financial services, education, healthcare and more.

The dilemma is that while standardisation assumes stable and predictable context and environment, healthcare operates with a mix of planned procedures and high degree of volatile workload and variance. The latter requires deep knowledge at the point of care to understand situational context. As a comparison, car body parts in a factory can easily be scanned toward industry standards. Patients are different, with hidden symptoms, unknown and unsure response to medication, mixed diagnoses and huge variance in mental, physical and social health conditions.

In our first article, we discussed the different levels of competency and proficiency (Dreyfus 1986). Standardisation plays an important role in healthcare, but can result in fatal outcomes without the application of analytical approaches onto new situations and deep tacit knowledge.

Empowering Subject Matter Experts

When building out their competency management strategies, employers need to balance the benefits of standardisation with the need to adjust to situational context and variance. The practical consequences of this is that employers can benefit largely from identifying those areas and competencies that are generic and cross-functional, while subject matter experts play an important role in owning and maintaining specific niche competencies. Ultimately, department heads are the key resource in terms of ensuring competencies for the best outcomes. The competency management framework and tools should be their toolbox and help them curate, manage and maintain competencies for their staff members. They are the first to know about the unmet competencies, better learning content available, the availability of their staff, etc. They need tools tailored to their context, not the one-size-fits-all-t-shirt. Think about the employers competency management as a combination of the global encyclopaedia paired with high-quality crowdsourced content by your subject matter experts on the frontline.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Berger B et al. (2021) Competency: Is It the Wonder ‘Drug’? HealthManagement.org – The Journal, 1(21): 642-644.

Dreyfus H (1986) Mind over machine (Reprint ed.). New York: Free Press.

Howe LC et al. (2019) When your doctor “gets it” and “gets you”: The critical role of competence and warmth in the patient–provider interaction. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10:475.

Poksinska B (2010) The current state of Lean implementation in health care: literature review. Quality Management in Health Care, 19(4):319-329.

Porter ME, Teisberg EO (2006) Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-based Competition on Results. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

Taylor FW (1911). The Principles of Scientific Management. New York, London: Harper & Brothers.

Tempel J, Ilmarinen J (2012) Arbeitsleben 2025: Das Haus der Arbeitsfähigkeit im Unternehmen bauen [Working life 2025: building the house of employability in the company]. Hamburg: VSA-Verlag.