HealthManagement, Volume 15 - Issue 3, 2015

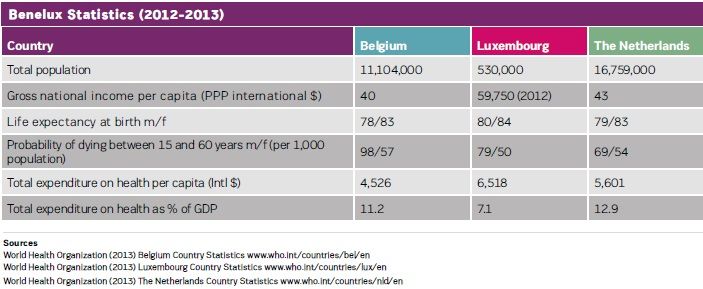

In Europe, euthanasia, the act of assisting with the death of a person at their express request, is only legal in Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg - the Benelux. This sensitive practice has strong voices both for and against. HealthManagement.org spoke to two leading advocates on the euthanasia issue. They shared their views on why they support or oppose this controversial act.

Opposed

DrKevinFitzpatrick, OBE has been spokesperson and researcher for Not Dead Yet, UK since 2010 and is the Director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition International. This year, he set up anti-euthanasia body Hope, Ireland. Dr. Fitzpatrick has been a paraplegic wheelchair user for more than 40 years.

I have been treated by the best practitioners over a 42-year stretch. I owe them and respect them enormously. This is in contrast to those few doctors who, despite any prowess they may have had, I would not let touch me.

Even the best practitioners however, can be surprised that all major disability rights groups oppose legalising assisted suicide/euthanasia. They know (as do we) that some people, disabled people included, come to consider an untimely death seriously. So what should be our response to those patients?

Everyone deserves the best care and treatment, as a human being, regardless of their situation. The question here is: must we legalise assisted suicide/ euthanasia so that we can support those in most dire need, as they ought to be supported? I am certain, after years of research, that it is entirely possible to seek the best end-of-life care for every citizen and yet oppose such laws – for reasons of their consequences.

ComplexIssue

Do we need to legalise assisted suicide/ euthanasia for reasons of patient choice and autonomy? Despite the rhetoric employed in the public forum, such laws concern protecting those who provide suicide assistance. Patient choice is an illusion: if the doctor refuses, the patient has no legal recourse. All choice, all responsibility passes into the hands of doctors, most of whom say they do not want it.

Perhaps pain is the issue? Palliative care specialists count ±2% of all cases with refractory symptoms that are so hard to manage. They have deep sedation, even in the light of double-effect, as an option. So too, withdrawal of futile treatment.

In particularly ‘hard cases’, end-of-life questions come when medicine says ‘We can do no more’ (except ease the process of dying). To end a human life is always a terrible thing, even in such dreadful circumstances. When (some) practitioners lose the sense of the awful burden they carry, when ending human life becomes routine, our whole culture,not just in medicine, is radically changed. Worse, when laws, are passed and even before, some people argue that ‘it is our moral duty’ to end those lives.

PeoplewithDisabilities

The problem for us (as disabled people) is that this false moral elevation of assisted suicide/euthanasia affects us most.We are seen as just plain obvious candidates for elimination. One Belgian government adviser was adamant in a public meeting that their law had been constructed for disabled people who, in his estimation, should want to die given their disability (his example was ‘a man with no arms and no legs’). The Supreme Court of Canada has just written into law (February 2015), the first time anywhere in the world, that being disabled is a sufficient reason of itself for an euthanasia death. Our lives are deemed ‘not worth living’ by those who have no real idea of what living our lives means to us, our spouses, children, wider families, our colleagues, the shopkeeper, the taxi driver and all.

So consider: an otherwise healthy young man approaches his GP to discuss his suicidal ideation. All suicide prevention services (we hope) are brought swiftly to bear; the extreme is ‘sectioning’ under mental health law. Why then, when a woman, born severely disabled, says “I want to die”, is the response “Well, yes - no-one could blame you?” Is that really compassion?

The difference in response is based solely on disability. It is paradigmatically disability discrimination, no matter how well-intentioned, compassionate, or otherwise and can be compounded by inexpe- rience, exhaustion, management/resource pressures, laziness, coercion, abuse and malevolence. These can appear in families, friends, carers - anyone directly involved in care of the patient.

Shifting Parameters

Holland, where the rise in the use of terminal sedation is truly alarming, and Belgium both said their laws would be only ever for terminally ill (eg cancer) patients suffering unbearably and with a very short time to live. Now psychiatric patients, disabled neonates, older people with dementia, people ‘tired of life’, and more, are being euthanised in both countries.

Belgian law has stated from the beginning that what is now called ‘existential suffering’ is alone sufficient for a euthanasia death. Now, a young woman with mental health issues, just 24 years old, who thinks ‘euthanasia is a nice idea’ is having ‘fun’ planning her own funeral. She has no other pathology and is not terminally ill, but was ‘granted’ a euthanasia death scheduled for August this year.

The constant refrain is: “We are not like them (Belgium, Holland). We are modelling our law on Oregon.” Oregon’s own department of health reports show clearly what motivates is ‘being a burden on others’ (40% in Oregon, 61% in Washington State). Oregon is no paragon: a terminally ill cancer patient with no private health insurance was informed by letter that the state’s insurance scheme could not afford their cancer treatment but that the patient qualified for the assisted suicide programme. Also, Oregon law allows no investigation after the death, does not require doctors to be present and heirs may facilitate the suicide. Who would know if the person who died had been coerced or suggestible in their vulnerable condition? Who is not vulnerable when faced with death as their only option?

These are just some of the complexities. Legislating for them all is impossible. It would surely have been done already.

We all need to respond to those who decide to die. But it is entirely consistent to resist moves to legalise euthanasia/assisted suicide when we see the consequences. Ending suffering by ending the life of the sufferer cannot be the blanket response. Fighting for the best palliative and social care and human support for anyone faced with the end of their lives is, I believe, the humane and compassionate response. Then maybe we can leave the easing of suffering of those people in the worst situations to the very best practitioners - the ones I mentioned at the start here.

Supporting

Dr.AyckeO.A.Smookisa retiredoncologist surgeon and the Presidentof pro-euthanasia body RtDE, Europe.He has been an advocate for thepractice since before it was legalisedin Holland in 2002.

“Voluntary euthanasia is not a choice between life and death, it is a choice between two different ways of dying.” Jacques Pohier

In 1993, The European branch of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies (WFRtDS founded in 1984) was founded by several end-of-life societies in Europe. Today it is RtDE which has 25 member societies in 16 European countries.

The aim of both organisations is to promote the right to self-determination by individuals facing death. This is based on the Lisbon Oath by the World Medical Association (WMA) which approves the right to die in dignity (1983).

The idea of self-determination at the end of life is not a new phenomenon. In the roaring twenties in Germany, discussion on topics like euthanasia end same sex marriages were a daily affair. In the UK the first Right to Die Society was founded in 1935.

After the Second World War the development of medical progress made it possible to do much more for patients. Many more patients could be cured and kept alive, sometimes against their wish. All over the world nurses in hospitals were confronted with patients with terminal illnesses and the attending physicians, just like Hippocrates, let the vulnerable patient down. Compassionate nurses however took the lead and hastened the death of the suffering patient often with an overdose of morphine or insulin.

DutchDefinitionofEuthanasia

In the Netherlands, euthanasia is under- stood to mean the termination of life by a doctor at the competent patient’s explicit request with the aim of putting an end to unbearable suffering with no prospect of improvement. It includes suicide with the assistance of a doctor. The voluntary nature of the patient’s request is crucial; euthanasia may only take place at the explicit request of the patient.

In 2001 the Dutch parliament adopted ‘The Termination of Life on request and assisted Suicide Act’ that came into effect in April 2002. In Belgium and Luxembourg a similar law was adopted a little later. On the whole, the law on euthanasia in the Benelux is, in effect, the same.

Criteria

- The request must be voluntary and well-considered;

- The patient’s suffering is unbearable and there is, despite the best palliative care, no prospect of improvement;

- The patient is aware of the diagnosis, their situation and the prognosis;

- The patient and the doctor must come to the joint conclusion that there is no other reasonable solution;

- The doctor has to consult at least one independent colleague, who must see the patient in person;

- The doctor must act with medical care and attention in terminating the patient’s life or assisting in their suicide;

- The doctor must perform euthanasia only on a patient in his care;

- The real value of talking about euthanasia does

not come from the act itself, but from the ability for the patient and his doctor

to speak openly about it.

Euthanasia is not:

- Painkilling

treatment that may shorten life;

- The administration

of lethal drugs to shorten life of persons who cannot express their will such as

severely defective new-born babies, incompetent patients and persons in a long-term

coma without a living will;

- Abstaining

from, or non-initiating life-prolonging treatment that is medically futile or is

rejected by the patient;

- Refraining

from medical treatmenton request of the patient;

- Terminal

sedation;

Recently I attended a play in Germany about a young man with terminal disease who needed to go to Switzerland for a dignified death because, in Germany, he could not be helped. His friends did not understand his self-determination. They left him and he had to go alone on his last trip to Switzerland in order to die in dignity. In the discussion afterwards two forum members, a palliative care doctor and the representative of the archbishop, expressed their disapproval of this situation out of fear that this would lead to ‘a slippery slope’.

Opponents always mistrust doctors’ integrity and perhaps, do not realise that for a doctor it is not easy to end a patient’s life. Also, although patients do not really want to end their lives, they want to end their suffering and the undignified situation there are in.

The majority of the audience at the play said that in Germany, they would like to have the options available in the Benelux. My contribution to the discussion: why are people envious of others who have the power to end their life in dignity?

My personal experience as a surgeon oncologist from 1984 onwards follows the progress in thinking about how to deal with patients in their final stage of life. My motivation to help patients to die has always been their longing for a dignified death. In the beginning of my practice, I performed aid-in-dying behind closed doors, as many compassionate doctors do around the world. We, the nurse and I, performed euthanasia according to guidelines that later became the standard. Amazingly, pain hardly ever was the reason for the request for euthanasia. It was always the loss of dignity. In many cases the desired death was a better perspective for the patient than enduring the misery of the sickbed.

Since 1985 in the Netherlands we have been able to discuss euthanasia more openly to the benefit of all involved. For the patient, the relatives and the friends a fond farewell has become possible and the process of mourning can begin before death. For proper euthanasia we use at present pentobarbital sodium or propofol with a muscle relaxant. Injecting the lethal drug is, without exception, a very emotional event for all concerned, but fortunately these emotions can now be shared.

It is amazing to see the power of patients in their final stage. In most cases they support the future surviving relatives instead of the other way around.

Two years ago, RtDE acquired an INgO (International Non-governmental Organisation) status at the Council of Europe after several years of trying. About 140 INgO’s meet twice a year in Strasbourg. We, as the board of RtDE are aware that we represent a ‘controversial’ issue. A lot of NgO’s nevertheless support the idea of euthanasia, though it is not their main subject.

In June, the RtDE had its 12th international biannual meeting in Berlin where we discussed, among other matters, the slow progress in Europe. It is three steps forwards and two backwards.