The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force in the European Union (EU) this month. It sets a high standard for consent and contains significantly more detail to bring together existing European guidance and good practice.

The changes reflect a more dynamic idea of consent: consent as an organic, ongoing and actively managed choice, and not simply a one off compliance box to tick and file away.

Doing consent well should put individuals in control, build customer trust and engagement and enhance organisations’ reputation.

What’s new about the GDPR compared to former data regulations?

• The GDPR is clear that an indication of consent must be unambiguous and involve a clear affirmative action

• Consent should be separate from other terms and conditions, and generally should not be a precondition of signing up to a service

• The GDPR specifically bans pre-ticked opt-in boxes

• It requires granular consent for distinct processing operations

• Organisations must keep clear records to demonstrate consent

• The GDPR gives a specific right to withdraw consent. You need to tell people about their right to withdraw and offer easy ways to withdraw consent at any time.

• Children can, from the age of 16, in certain situations for online services now provide their own consent (although awaiting confirmation via the Data Protection Bill as a decision for each member state)

What are the penalties if you get GDPR wrong?

Relying on inappropriate or invalid consent could destroy trust and harm your organisation’s reputation.

It may leave organisations open to substantial fines under the GDPR. Article 83(5)(a) of GDPR states that infringements of the basic principle for processing personal data, including the conditions for consent, are subject to the highest tier of administrative fines. This could mean a fine of up to 20 million euros or 4 percent of total annual turnover, whichever is higher.

Definition of GDPR consent

Consent can now only be valid if it is explicitly given. There will be no alternatives such as silence or inactivity by the customer or clients.

The GDPR definition is: “any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subjects’ wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.”

Options for dealing with consent

There are 6 routes or options for dealing with consent:

1) Explicit consent is one way to lawfully process data.

Organisations will still be able to process personal data without consent if it’s necessary for:

2) A contract with the Individual

3) Compliance with a legal obligation

4) Protecting the vital interests of a person (Article 6(1)(d))

5) A public task – to carry out a public function or a task in the public interest or exercise official authority (Article 6(1)(e))

6) Legitimate interests (generally not appropriate to be used)

It is likely that most healthcare organisations can use number 5 ‘A public task’ or in some circumstances may be able to use number 4 ‘Protecting the vital interests of a person’ where life or death scenarios apply.

Healthcare services need to determine the lawful basis for processing, ie What legislation do they work within that allows them to collect personal data for that task?

Services may need consent for most marketing calls or messages, website cookies, online tracking and installing apps or software on people’s devices.

Special category data

Healthcare organisations will also need to process special category (sensitive) personal data.

To process this under the GDPR organisations will need to apply one of the conditions listed within Article 9(2). These conditions for processing are more limited and specific, and they include provisions covering obligations under employment law, health and social care, public health, legal claims and research purposes.

Explicit consent

Explicit consent is one option for legitimising the use of special category data.

Explicit consent needs to be:

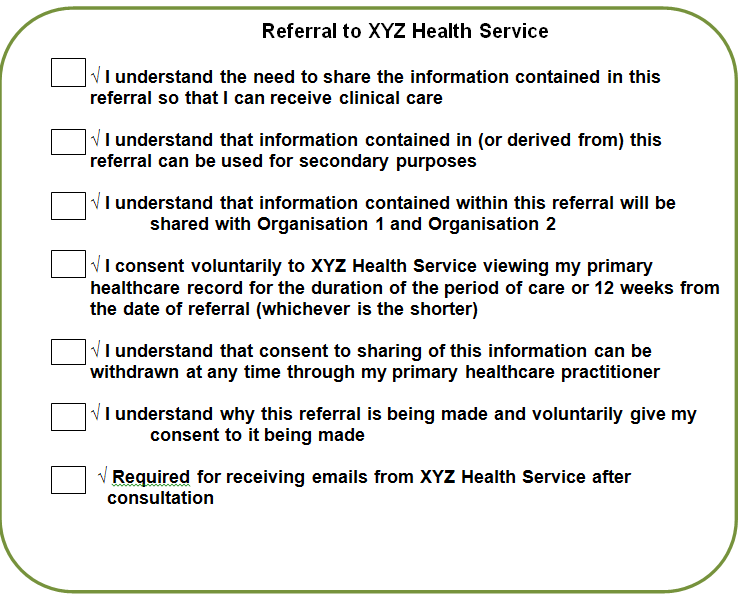

• specific

• granular

• clear

• prominent

• opt –in

• documented

• easily withdrawn.

This should be reviewed and refreshed on a regular basis or when something changes. Explicit consent can also expire if a period for the processing is specified.

1) Unbundled: Consent request must be separate from other terms and conditions. Consent should not be a precondition of signing up to a service unless necessary for that service.

2) Active Opt-in: pre ticked opt-in boxes will be invalid – use un-ticked opt-in boxes or similar active opt-in methods.

3) Granular: give granular options to consent separately to different types of processing wherever appropriate. One for all is no longer acceptable.

For example:

4) Named: Include the name of your organisation and any third parties who will be relying on specific consent – even precisely defined ‘categories’ of third party organisations will not be acceptable under the GDPR e.g. You cannot say ‘Voluntary Organisations’.

5) Documented: keep records to demonstrate what the individual has consented to, including what they were told, and when and how they consented. Set a review date if appropriate including date of withdrawal of consent.

6) Easy to withdraw: tell people they have the right to withdraw their consent at any time, and how to do this. It must be as easy to withdraw as it was to give consent – have simple and effective withdrawal mechanisms in place such as a telephone number or an online tick box.

7) No Imbalance in the relationship: consent will not be freely given if there is an imbalance in the relationship between the individuals and the Data Controller. This is where a patient or service user depends on services and fears consequences if they feel they have no choice but to agree. This will also make consent difficult for employers in particular, who should seek an alternative lawful basis.

When is consent appropriate or not?

• Explicit consent will be appropriate if the organisation can offer people a real choice and control over how their data is used – if services cannot offer genuine choice then explicit consent is not appropriate

• If the organisation would still process the personal data without consent, asking for consent is misleading and unfair.

• Public authorities, employers and other organisations in a position of power over individuals should avoid relying on consent

Action points

1. Each service needs to know what information it’s processing and ensure that this is reflected in an accurate entry in the organisation’s data mapping processes. This information is used for an accurate and up-to-date information asset register leading to information sharing agreements, one of the requirements of GDPR.

2. Services need to consider what their lawful basis for processing personal data is (what legislation allows them to obtain and process personal data) and record this, preferably via the data mapping process.

3. If there is not a lawful basis, services will need to consider if they can justify the process to protect a person, or decide if they need to obtain explicit consent and keep records of this consent.

4. Review existing consent mechanisms to ensure they are still compliant.

5. Re-word specific consent options where a lawful or other basis is not applicable: this will need to include clear and concise notices.

Latest Articles

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force in the European Union (EU) this month. It sets a high standard for consent and contains significantly more detail to bring together existing European guidance and good practice.